Introduction

Innovation is defined here as an idea or a process that changes the status quo for the better; bringing positive difference to the way things are done, satisfying specific needs and improving the quality of life of people in general.

Innovation can bring a change that is ‘revolutionary’ or ‘evolutionary’. Takaful is innovation in the field of insurance. It brings change in status quo of insurance solutions for many who previously had no option other than conventional insurance. Takaful in fact brings a revolutionary change to those for whom conventional insurance was a ‘no-go’ area due to religious reasons. The revolutionary shift is about how money is ought to be managed, invested and dispersed within the context of risk and reward and in the sharing of risk. Evolutionary innovation in takaful is in terms of its products and services and the value and satisfaction this is supposed to bring to its customers.

The ethics of takaful is what makes it a revolutionary innovation for the insurance market. There are of course certain areas where there is no need to reinvent the wheel; why do things differently for the sake of being different? This is because takaful is essentially insurance, providing financial protection. It compensates financially for loss and damage due to unforeseen risks just like conventional insurance. It is bound by and based on similar scientific rules and actuarial approaches to mortality rates, morbidity rates, loss ratios, claims experience and discounted cash flows for calculating price of risk and evaluation of liabilities. In fact the existing technical aspect of insurance is the leverage available to takaful. This should help takaful to consolidate and move forward to evolutionary innovative process embedded in the ethical base of Shari’a principles. These principles provide strong ethics to the ownership of risk and reward and to the application of mathematics of cooperation all the way to the use of money for the greater good of society and environment.

Takaful and cooperation

The stakeholders of takaful (customers, shareholders, regulators and the management) need to have a good understanding of what is meant by cooperation and cooperative principles as this is the revolutionary aspect of the ethics of takaful.

Cooperation is a binding force of nature. Just as cells work together to produce the valuable nutrients of life, so do humans work together like cells in the body of humanity. Cooperation brings strength to society and community and enables us to go through life against its rigors both natural and manmade.

Cooperation is indeed the very essence of takaful, of risk sharing. It works at the cost of self-interest. You give up a little to gain collective strength which brings greater reward for the cooperating group and cooperating community and society. This equally applies to businesses where if these are run with social conscience it is for the collective benefit of the community and society at large, the very essence of Islamic finance.

The participants and shareholders are two pieces of string intertwined to make takaful work. One cannot exist without the other. Takaful is not proprietary nor is it mutual, but it is both. The essence here is to embrace both the participants and the shareholders as one body of cooperation. This brings prosperity to society and the environment through channelling wealth and capital, with social conscience and responsibility, in fairness for the risk undertaken and shared.

The concepts are designed to provide just reward, encouraging the distribution of wealth through savings and insurance protection based on equity, justice and fair play. The cooperative principles help to enlarge the system as a caring and transparent system, for the welfare of society, free from exploitation. The sum total of wealth flowing through this system is directed to geneate economic activity in businesses that are both socially responsible and eco-friendly, avoid social ills that can otherwise arise from the creation of money from money, and link deposits and investments to real underlying assets for a sustainable takaful proposition.

Takaful participation is intangible, a financial protection against physical mishaps that may or may not happen. The concept of cooperation is also intangible as a customer seeking to protect his home against financial ruin due to fire, flood or other accidents does not know or cannot see other customers with whom he or she is participating. However, there is mathematics behind this that brings confidence in the cooperative concepts — an element of tangibility that what we are agreeing to today in terms of protecting each other will work in future. This is based on empirical evidence of the law of large numbers, which works if it is managed and controlled in certain technical applications.

The growth of takaful

Up until year 2000, the takaful industry’s growth was pedestrian, having gone through the pioneering years of late 1970’s and 1980’s of setting it up. The revolutionary change of innovation was driven by the entrepreneurial spirit of few who had the means and the will to succeed in bringing Shari’a’s application into the financial and commercial dealings for Muslims. For a good part of 20 years in the 1980’s and 1990’s, when Islamic Banking was getting stronger, the takaful industry debated and dwelled upon ways to succeed further goaded by the governments of Malaysia and Bahrain and entrepreneurs from Saudi Arabia, Bah- rain, the UAE, Kuwait, Qatar and Malaysia.

It was not until after year 2000 that the takaful industry took off, more so by 2003. Many markets experienced the introduction of takaful for the first time, and others saw not two, but several takaful companies getting established. Retakaful companies grew in number. Industry associations and compliance bodies were formed. More regulators recognised takaful and the global players suddenly wanted to be part of it all.

In 2011, we find the industry fragmented with around 200 takaful companies and windows globally. The small and young industry of takaful is going through a long consolidation phase; to find its position within the larger universe of conventional insurance in which it must compete. It is a difficult phase as new operations are driven to gain critical mass soon after establishment to meet the expectations of both participants and shareholders, in conditions that are not wholly conducive. In a quest to establish and grow, the race has been often to grow too fast too quickly, taking shortcuts on the way and bypassing ethical aspects of the business. The Shari’a advisors have an important role to play, but in many instances this has been weak. The regulatory environment has not been entirely conducive to takaful businesses (with few exceptions) and the general mindset of the operators and regulators has been to think of takaful as a niche, accommodating it within the conventional framework.

The revolutionary introduction of the idea of takaful was back in the 70s and takaful was first introduced in 1979 in Sudan. Takaful should have been well on its way to evolutionary process of innovation but has faced considerable challenges. As the industry settles in its consolidation phase, the companies and markets that truly focus on the ethics of takaful stand to take a lead in the innovative achievement much more than has been the experience to date.

Achievements in takaful

The takaful industry has progressed in the following ar- eas in its evolutionary process of innovation:

- Distribution: Thanks to the evolution of takaful, it has contributed hugely to the growth of bancassurance or, more specifically, banctakaful globally. This has been the most successful means of distribution, especially for individual life/family takaful. Banctakaful comes as a natural fit from ownership of takaful companies by banks. It is estimated that more than 80% of takaful life retail business is generated through this channel in the GCC. There are other modes of distribution based on small cooperatives and associations traditionally found within communities as part of cultural and social set-up. These are best suited to the ethics of takaful, especially in micro-takaful serving the disadvantaged segments of our society.

- White labeling: This is where a takaful company in one jurisdiction offers its products usually with a plug-and-play administration system to licensed operators in other jurisdictions, thereby enabling young and in-experienced local takaful companies to be able to offer sophisticated products at a fraction of a cost. This approach helped to fast track the growth of family takaful products in markets where otherwise it would have taken much longer to reach various types of customer segments.

- Products: Takaful companies offer almost all types of products that are available on conventional basis. There are three areas where there are gaps: a) in covering mega risks such as in Oil and Energy, catastrophic risks etc, due to lack of capacity, b) in providing pension annuity products and schemes due to lack of appropriate long-term fixed income assets, and c) in micro-takaful where very little work has taken place with few exceptions such as Sri Lanka and Malaysia, but even here more active role is needed by the industry.

Some examples of unique takaful offerings are given below:

- There are benefits that can only be offered in takaful products. One example is Badal Haji benefit where someone else performs the rites of Hajj on behalf of the participant (policyholder). In the event of death or total permanent disability of the participant, a part of the benefit under the policy (out of funds invested in compliance with Shari’a principles) is used to finance the performing of Hajj Badal. This ensures that the par- ticipants will not be financially disadvantaged in fulfilling one of their obligations towards the five pillars of Islam soonest possible.

- Benefits conceptually relating to cultural and religious aspects. One such product is based on provisioning in good years for meeting hardship in bad years like the seven good years and seven bad years. Contributions under this policy are paid by participants for seven years and benefits last for 14 years. The concept relates to Ayah 43 of the Quran where king of Egypt says: “Verily, I saw (in a dream) seven fat cows, whom seven lean ones were devouring – and of seven green ears of corn and (seven) others dry.

- Cooperative principles: These principles are the foundations of takaful and yet, an average takaful customer has very little experience of it. Sudan is one market where the participants are invited to a general gathering once a year and have the opportunity to feel the spirit of cooperation. This approach is yet to be adapted more widely by the industry and is a great way to cement customer-operator relationship. The marketing budgets would be well spent in supporting such events.

- Takaful regulations: Dedicated takaful regulations have facilitated the growth and development of takaf- ul in Malaysia, Bahrain, Pakistan and the UAE. Similar moves are in progress for Oman. Saudi Arabia has cooperative insurance law based on Shari’a principles, but the system is distinct in not requiring takaful models, surplus sharing nor qard rules that generally apply to takaful in all other markets.

- Standardisation of Shari’a compliance: There are many different takaful models practiced within the industry and Shari’a compliance varies from paying a mere lip service to it, to adhering fully to the principles. Malaysia has taken the lead in ensuring that companies observe strict Shari’a compliance through a central Shari’a Advisory body under the ambit of the Regulator. This body aims to target an effective Shari’a framework to harmonise the Shari’a interpretations and strengthen the regulatory and supervisory oversight of the industry. The central body sets the rules and procedures in the establishment of a Shari’a Committee of takaful company and defines the roles and responsibilities of the Committee.

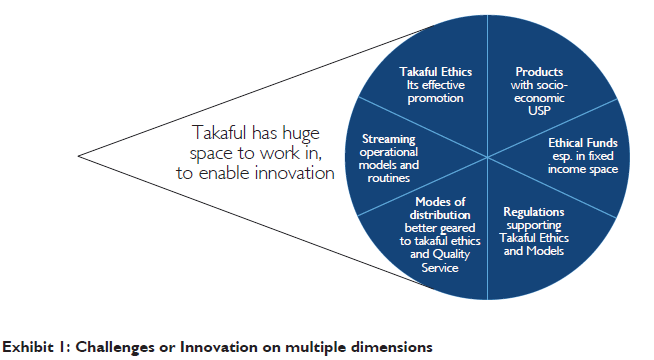

Challenges to innovation in takaful

- Weak marketing of takaful ethics

- Lack of consensus amongst regulators on standardisation

- Lack of Operational Standardisation

- The ‘niche’ mentality about takaful

- Limited asset range in the fixed income category including sukuks

The real meaning of takaful has not been getting across to customers. Equally, despite so many established takaful companies, the takaful industry remains a niche even in markets where Islamic finance is considerable. The models on which the industry is operating have certain gaps when it comes to managing underwriting risks as well as business risks effectively.

The concepts of cooperation (risk sharing and qard) are fine on a juristic basis but as experience unfolds over time, pockets of constriction are highlighted; for example, the extent of reserving needed income for insured events that may or may not happen in future. The source of such reserves is the contribution itself donated by participants that includes the wakala fee to cover business expenses as well as a margin towards return on capital for the shareholders.

The question is what is the right way of deciding how large should be the wakala fee, and for how long can the remainder of aggregate contributions continue to be put aside as reserves before some of it can be distributed back to eligible donors as a reward for risk sharing. This happens over time as donors join and leave in a continuous flux. If a surplus is distributed it may not necessarily go back to the ones who had contributed towards it as they may have left the scheme. This may be acceptable at the takaful level within the spirit of cooperative principles, but at the retakaful level it leads to questions of commercial viability where takaful companies have shown reluctance to accept.

Where the risk is priced or underwritten incorrectly or reserved insufficiently (and the chances of this happening in General Takaful are much more than in Family Takaful) then claims can exceed the available reserves, creating deficits that must be supported through qard (benevolent loan) by shareholders, out of their capital. In practice we see imposition of arbitrary limits on wakala fees, on mudaraba share of investment returns and on performance incentive fees (if allowed). The arbitrariness of these limits creates financial imbalances and impedes the ability of takaful companies to take on new business with different risks.

These are not juristic matters, but technical matters that beg the question of applying mathematical models in assessing long-term impact on the durability of business of takaful within each company. Each company ends up with its unique risk profile driven by the types of risks it is writing and creating specific burden of qard on shareholders. How can this burden be minimised? At what level can wakala fees adequately service the business expense? The level of fees need to be commensurate with the degree of maturity of business, whether it is a new company or an old established company within the constraints of price at which new business can be written.

What is a fair balance in fixing the percentage of investment returns and underwriting returns to satisfy the concept of risk and reward within the principles of cooperation (risk sharing)? Are we clear in establishing the impact of risk, where it is located, either with participants or ‘shared’ with shareholders, of how the applicable models enable us (or don’t) to manage qard due to excessive impact of risk within the principles of risk sharing. When such deficits are recurring or become irrecoverable, the impact of risk ends up with the shareholders. Is this workable within the larger picture of building a sustainable and durable takaful business, managed on commercial basis?

These are fundamental issues where more understanding is needed between Shari’a advisors and takaful operators with the help of mathematical explanation of risk models that can highlight the impact of risk on reserves and qard.

If the level of reserves and fees is kept within the realms of mathematics for finding best fit, built on mutual cooperative principles, embracing not just the participants but also the shareholders as one big cooperating community, then many of the inequities disappear, resulting in the following:

- The interests of participants and shareholders are aligned without upsetting the core values of takaful (avoiding and minimising gharar, maysir and riba). The principles of risk sharing recognise the shareholders’ support without which the impact of risk remains unwieldy.

- The shareholders’ role to be the lender of last resort may be recognised within the juristic realm as an obligation as this is about the technical nature of the business within the overall juristic parameters and fits in well with the regulatory requirements of capital backing.

- The wakala fees are geared towards only the expenses for running the business, pushing down maxi-mum limits within which the wakil must charge these fees to pay for expenses. If a wakil is running a high expense bill then that reflects his mismanagement more than anything else. Any returns to the shareholders are de-linked from the wakil’s management fees (that come from fixed and known amounts paid by the participants as contributions) and linked more to variable source of surplus/deficit of business in the spirit of risk and reward going hand in hand. There are different considerations for a retakaful company where wakala fees could be a source for not just the expenses but a margin for irrecoverable qard. Qard can become irrecoverable where a participant takaful company runs a deficit and is eventually unable to transact. The re-takaful company will not have any recourse to recover this qard as other participating takaful companies may resist in sharing this burden.

- It enables the wakil to compete better in the market due to the facility of risk-based capital available from the shareholders.

- The performance incentive fee for the shareholders is seen as a just reward for the risk taken by them.

Conclusion

The future growth and success of takaful is very much dependant on the mathematics of cooperation, in finding solutions to issues highlighted above. The industry urgently needs concerted effort to address these challenges to innovate and create a better environment for its success.