Wealth management departments became a common sight in most commercial conventional and Islamic banks by the late 1990s. Banks offered special products to HNWIs, and each financial institution developed its own definition of a HNWI. In an environment of low interest rates, such HNWIs were looking for higher yields but preferred to channel their money though their trusted banker. UHNWIs were targeted by private bankers. Private banks spun off from being mere departments of large banks to subsidiaries in their own right, governed by a unique set of regulations. Wealth management departments, however, remained within the ambit of a commercial bank’s regulatory environment. A customer with a US$100 balance would qualify as a normal retail customer, a customer with US$10,000 in an account would be a priority customer, and banks would refer such customers to their asset management groups or other companies within the same corporate group. Customers with balances of say US$100,000 and above may be offered wealth products and be assigned to a special relationship manager. Customers with US$1,000,000 would be typically assigned a private banker. These customers would be offered additional products, such as currency investments, opportunities to invest in stock markets, opportunities to invest in fixed-income instruments, alternative asset classes and even real estate.

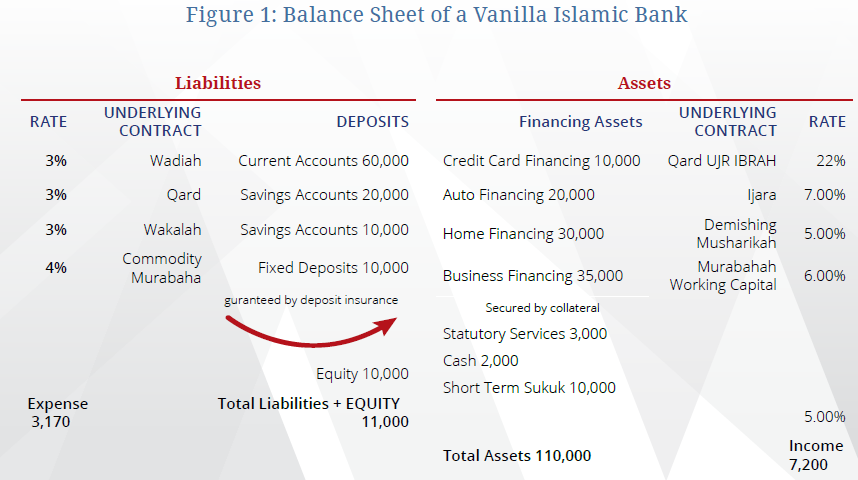

However, typically a banking licence limits the investment opportunities granted to a bank for their depositors. A vanilla bank simply mobilises deposits on the liability side of its balance sheet and uses these funds (after setting aside statutory reserves) to fund assets that by and large are receivables created by selling assets on credit, leasing assets, or a combination of both.

The balance sheet above reflects the positions of a vanilla Islamic bank. What is important to understand that equity is offered by shareholders as a buffer for unexpected losses, whereas impairment charges are deducted from profits to cover expected losses associated with the business of credit. A detailed discussion on these topics can be found in Contracts and Deals in Islamic Banking by Kureshi and Hayat. Deposits mobilised under the contracts of wad’ia, wakala, qard and even mudaraba are guaranteed by Islamic banks, and protected under deposit takaful schemes. Due to this stipulation of guaranteeing deposits, regulators control how Islamic banks can utilise the money of depositors. Financing is extended to “credit-worthy” clients and collateral is secured to protect the money fund providers from credit events.

Shareholders equity is not used to finance assets, but is used to purchase short-term, A rated, liquid assets that can be quickly converted to cash to cover losses and liquidity crunches.

The Islamic bank earns a spread from the profit it earns on selling assets on credit or leasing them, in our example this is US$7,200 – US$3,170 = US$4,030. The Islamic bank will deduct further expensesof salaries, facilities, fixed assets and taxes, and the residual is then distributed to shareholders as dividends or ploughed back into the business. Assuming that the Islamic bank is left with US$1,500 after meeting all other expenses and taxes, this reflects a return on equity of 15%.

However, depositors, the main fund providers, only earn a maximum of 4% on their funds. Customers seeking higher returns may then approach our Islamic bank for higher returns. In the vanilla bank described above fund providers, have no control over the kind of clients their money is used to finance. In fact under Customer Privacy Laws, funds providers cannot by law know the other fund providers or the recipients of financing. Depositors also have no control over Islamic banks credit policies, credit screening methodology or monitoring systems. Typically retail customers are handled by the consumer banking department of an Islamic bank, whereas institutional customers are managed by the corporate banking division.

Structured Products, Customers, Product Developers and Regulators

Structured products are Over The Counter (OTC) products, they are often customized to meet the specific risk-return profile of individual customers. Customers have some control over how their funds are channelled, and what kind of assets their money can fund. For instance if a customer with US$10 in the bank instructs the bank to finance the government of Greece by buying Greek sukuk, assuming regulatory relaxation, an Islamic bank can do exactly just that. This product and its price would be structured individually for such customer. It would be developed under a wakala contract where an Islamic bank acts like an agent (like an asset manager) and invests the moneys of the customer at his or her request in an asset class of his or her choice. What is important to understand is that the funds may not be guaranteed by the Islamic bank in this case and also may not come under any country’s deposit takaful scheme.

Structure products allow, fund providers a one window shop to invest in such financing arrangements that may not be the typical business of the bank, in equities, in fixed income sukuk, in currencies, in futures, in commodity futures, indexes, options, and even real estate. Each asset class offers its own risk profile and customers are allowed to pick an asset class or a combination of asset classes. The higher the risk associated with an asset, the higher the return. Thus, the customer base of structured products is typically rather more sophisticated and cognizant of financial analyses than the normal retail or commercial banking customer. In fact most Islamic banks must inform the central banks of their jurisdictions of the profiles of the customers who have purchased structured products to ensure that complicated products are not being offered to unassuming depositors.

As structured products typically involve capital markets instruments, structured products come under the ambit of not only a central bank but also of the capital markets regulator or the securities commission of a country. Structured products thus must be approved not only by a central bank but also the SC, not only for their structures but also for their target customer markets. In the case of Shari’a-compliant structured products, the Shari’a committee of the Islamic bank, the central bank and the securities commission must endorse the underlying products. Finally, given the complexity of structured products, they are typically developed not by the retail banking product teams, but by the investment banking product teams. Branches of Islamic banks then serve as distribution channels for these products. These products are typically owned by various product managers, and at times it is difficult to identify what department is responsible for the performance of the product as a whole. This is a corporate governance issue here and not the subject of this chapter.

Now that we have some understanding of the background we can investigate certain structured products.

Vanilla Equity Product

A vanilla product would simply invest in pools of equities based upon their risk-return profiles. Different stocks behave differently in different economic environments. The risk associated in investing in a stock is a measure of the volatility of the stocks returns and its deviation from its mean. These analyses range from rather simple statistical analysis of a stocks past performance to complex models that predict future levels. Such simple calculations as mean, standard deviation, variance, co-variance, correlation coefficient, beta, along with the Capital Asset Pricing Models are used to determine risk-return models. Equities are pooled according to their risk-return profiles. Stable stocks often do not vary far from the mean either above or below the average price of a stock (in industry language – 52-week average). Such stocks although offer limited capital gains opportunities and most returns come from dividend payouts. Investors are merely required to predict the frequency and volume of dividends over a holding period and discount them back to come up with a fair value of their asset choice.

Volatile stocks offer higher returns possibilities as well as a potential for greater losses. The downside is hedged with such trading techniques as short selling a portion of the portfolio, put options or stop loss orders, but these instruments add to the cost of the transactions.

Investment banks may simply purchase stocks for a client, a pool of stocks according to risk profiles, or invest in actual indices such as the KSE Shari’a 100 or Dow Jones Shari’a Nikkei 200. The actual purchases of the stocks are made through an asset management firm and a broker. Investment banks may develop varieties products with different upside benefits coupled with downside losses.

For instance a product may offer capital guarantees but a maximum return of 5% over a holding period, or 95% capital guarantees with an upside of 7% and a maximum loss of 5%. Other combinations may not offer capital guarantees at all and upsides of 20% to 30%.

Investment banks then act as an agent of their client, and earn an agency or wakala fee executing the transactions, much like an asset management firm.

Equity Linked Product

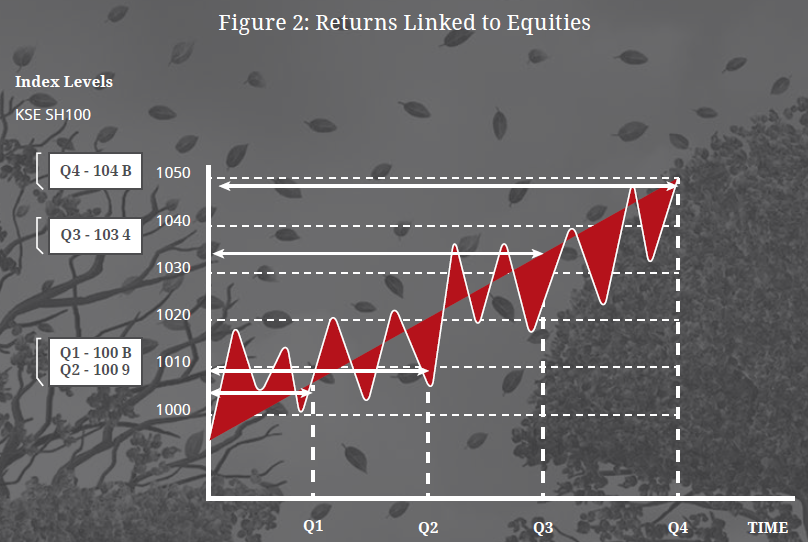

Alternatively, an Islamic bank may offer returns that use a particular index as a benchmark only. In this event an Islamic bank mobilises deposits from customers, and offers returns linked to the performance of a Shari’a-compliant index, like the KLCI Shari’a Index for instance. The Islamic bank may invest the funds mobilised in the normal financing activities of the bank, or may even invest the funds in more risky assets such as binary options, or foreign currency options, and hope to generate more returns from these activities than the benchmark index. The difference between the Islamic banks returns from their trading activities and the benchmark are the profits for the bank. These products are typically not capital guaranteed, and require the customer to place funds with the bank for at least one financial quarter if not a full year. Certain structured products offered by Islamic banks even link returns to non-Shari’a-compliant indices and asset classes which has been a rather controversial issue in the industry.

Figure 2 illustrates the returns experienced by an equity or a pool of equities over a period of 4 quarters. In the first quarter the index increases by 8 points, in the second by one additional point to reach 1009. In quarter 3, the index reaches 1034, with a dramatic increase and in quarter 4, the index hits 1048. A structured product can offer a variety of returns to the customer based upon the behaviour of the underlying index or asset class. For instance a quarterly payout may be linked to a quarterly performance. Say if the equity price or index appreciates by 5 points in a quarter, the product will offer a return of 5% per annum, and if the index appreciates by only one point the product will offer no returns.

Other combinations may look at the performance of the index or equity class for the full period of 4 quarters and offer a payout of say 7% if the index rises by 20 points from the base period.

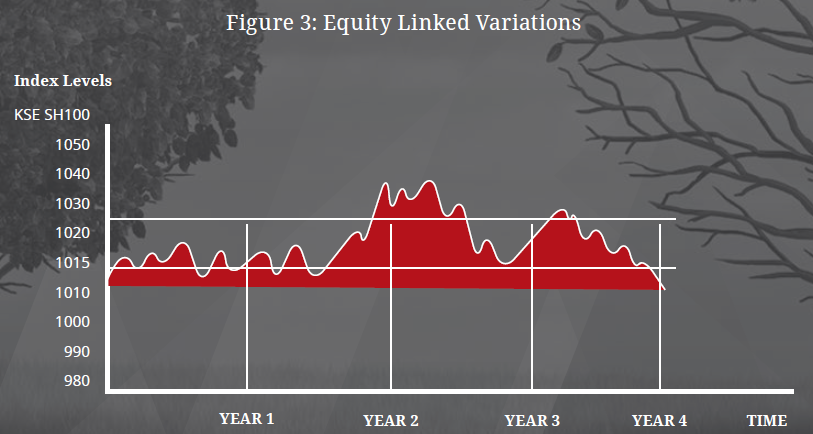

A 5 year callable structure offered by certain Islamic banks offer a payout only after 5 years and that too if the index hits a certain level at least an x number of times during the life of the product. For every year that an index fails to hit a certain level, the product discounts returns by 3%. So lets say a product offers 15% over a 5 year period, with payouts at the end of the five year period and holds a benchmark level of say 1030, payouts may be as follows. The product may be so structured that for every year the index crosses 1030, the product offers 15% returns, but for every year the index falls below 1015, the product offers on 2% returns. If in any given year the index hits both levels, the product will offer 7% returns. For levels between 1015 and 1030, the product will offer 10% returns if none of the barriers are reached. Figure 3 illustrates how a certain equity behaves, with the upper bar being crossed in Year 2 and Year 4, but the lower barrier also crosses in Year 1, Year 2 and year 4. Thus returns, for Year 1 would be 2%, for Year 2 they would be 7%, for Year 15% and for Year 4 again 7%.

What is obvious in these products is that Islamic banks do not necessarily invest in the asset classes whose returns they mirror or benchmark, as this would just earn them an agency fee. They would have to invest moneys in a host of other assets that may outperform their benchmark or alternatively may even underperform their benchmark. A complex combination of options are used to hedge risks, and this brings us into another controversial world of options. Under the Shari’a, options are developed cot under the law of contracts but under the ambit of promissory undertakings or wa’ad. In a option, a purchase or sale of an asset is contingent upon an event, typically changes in the prices of the asset upon which one party issues a counterparty an option to buy or sell. A counterparty promises to purchase the underlying asset, but is not obliged to do at a future time, for a specified price. The seller of an option is however required to make good, in the event the buyer exercises his or her rights. As there is no transfer of ownership of an asset when the agreement is entered upon, the agreement is not recognized by contract law as interpreted by Shari’a scholars. For a detailed exposition on options the reader is asked to refer to Financial Engineering in Islamic Finance, the Way Forward, A Case for Islamic Derivatives by Hayat, Kureshi and Mukhsia. Further, a promise to buy/sell, in the conventional universe, or an option, carries its own consideration, i.e., price and enforcement. It is a promise and can only be enforced where legally a promise is considered legally binding. In the world of common law, a promissory estoppel is referred to in the following words. “In a contractual setting, the parties can say or do things that induce the other to act to their detriment. Undertakings that induce reliance may be enforceable via the doctrine of promissory estoppel (also known as equitable estoppel), even absent consideration of formality. Promissory estoppel is one application of the broader equitable principle of estoppel which is a “principle of justice and equity’.

A structured product involving the sale of an option or purchase of an option requires the permissibility of an option agreement, the pricing of an option agreement, a liquid market to trade the contract and a Shari’a-compliant counterparty. We shall go into some more details here when discussing Dual Currency Investment Account–i.

Sukuk and Alternative Asset Class Linked Structured Products

Similar products can be developed by merely changing the benchmark asset class. It can be the performance of sukuk, 3 month mudaraba rates on interbank placements, returns on Shari’a-compliant commodities like gold, oil, aluminium etc. Returns can be benchmarked to real estate prices, Shari’a-compliant indices, prices of currencies or any other Shari’a-compliant asset. Payouts would be linked to the behaviour of the prices of these asset classes.

Dual Currency Investment-i

This product is on the shelf of several Islamic banks in Kuala Lumpur. The product is marketed as a dual currency option plan, but regrettably the risks are not clearly made clear to clients. The product is rather simple in itself, but before we explain the product we want to develop some background. Any commercial banks that deals in foreign currency, buys and sells currencies for their clients and for their own book. Let us assume a Malaysian customer wishes to buy US$10,000 and the exchange rates between both currencies is US$1 = MYR3. This rate is communicated on Reuters ticker board, and now even on google and yahoo finance websites. However, when the customer approaches the bank for the purchase, the bank will always quote a price like US$1=MYR 3.05. The bank will take MYR30,500 from the customer, but will actually only pay MYR30,000 to the seller of the dollar, making a tidy exchange income of MYR500. The DC-I products claims to allow customers to choose their own price, say US$1=MYR3.02. A currency pair is chosen by a customer, it can be US$/Yen, Yuan/US$, MYR/SingUS$ or any other such pair, and an exchange price or exercise price is selected by the client. Assuming the Islamic bank we are referring to is XYZ Islamic which is a subsidiary of XYZ conventional.

Now, the client will appoint XYZ Islamic as its agent to conduct certain transactions. XYZ Islamic will write a call option on the currency pair, allowing the buyer of the option to choose whether to convert the base currency (US$) into MYR or not. The client deposits, MYR30,200 with XYZ Islamic. The bank contracts to offer a 3% return on the deposit in 90 days or US$10,000 in cash to the client, depending on the movements in US$/MYR exchange rates. Thus, either the customer will get back MYR30,200 + MYR226.50 = MYR 30,426.50 or the customer will get US$10,000. Just as a note the two amounts are equal at an exchange rate of US$1 = MYR 3.04265, an appreciation in the value of the US$ by .75% in 90 days. Let us not forget, the strike price is thus, US$1 = MYR 3.02.

XYZ Islamic sells the call option to a counterparty, which can be the conventional parent bank, or could be a Shari’a-compliant asset management company or counterparty. The price of the option is added to the customer’s deposit of MYR30,200. Let us assume this is MYR100. Now the customers balance has become MYR 30,300, and the bank needs to cough up an additional (30,426.50 – 30,300) MYR126.50 to pay to the customer. However, the sale of the option exposes the client to performance risk.

If at the end of 90 days, the exchange rate between the US$ and the MYR is US$1 = MYR3.04265, and the bank exercises the call option to buy ringitts from the client for US$1=MYR3.02, then the bank can opt to sell US$ and buy the MYR30,426.50 payout owed to the customer. To buy MYR30,426.50 at a rate of US$1=MYR 3.02 (the exercise price) the bank will cough up

US$10,075. If the bank sells this sum back for dollars at market rates where US$1 = MYR3.04264, these MYR30,426.50 will only get the bank US$910,000. The bank would make a loss on this transaction of US$75 and thus choose not to exercise the option and the customer walks away with MYR30,426.50 in 90 days or a profit of MYR226.50.

However, if the exchange rate takes a reverse stride and is US$1=MYR3.01, then let us see what happens. If the bank exercises the call option at the exercise price of US$1=MYR3.02, and buys MYR30,426.40, the bank will have to pay, US$10,075 as before. The bank then uses these ringitts to buy dollars, at market rates of US$1=MYR3.01, and with MYR30,426.50 is able to buy US$10,108.47 from the open markets making a profit of US$10,108.47 – US$10,075 = US$33.47. The customer on the other hand will have US$10,075 in their account which will have a market price of only MYR30,325.75. In this regard, the customer only made a profit over principal of MYR125.75, a full loss of MYR 100.75 from the previous scenario.

If the exchange rate fall to US$1=MYR 2.95, the bank will end up with US$10,314.067, and the customer with, MYR 29,721.25. In this latter scenario, the customer stands to even lose some of the principal invested in the product.

Ultimately, it is the bank that decides in what currency the customer gets paid and not vice versa. This is not fully explained to customers unfortunately.

Dual Currency Commodity Murabaha

Many commentators feel that given Islamic finance is developed on a framework of sale transactions, this restricts the opportunities for product development. On the contrary in a right tax and legislative environment, we feel this actually opens up the door for product development.

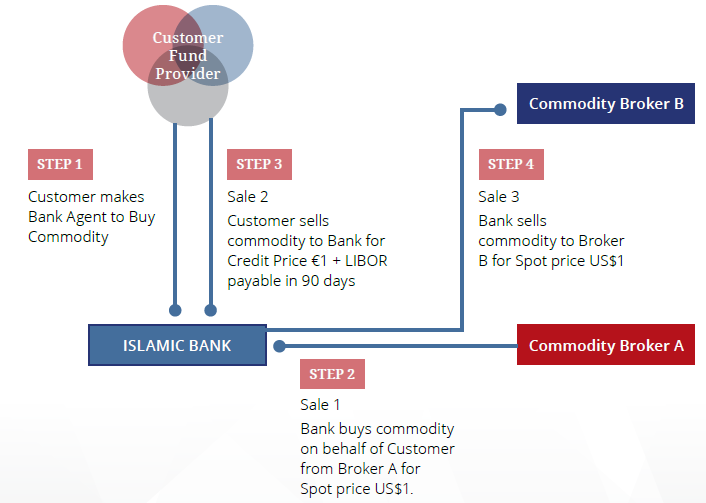

Tawarruq and commodity murabaha are two structures most readers would be familiar with. The structure involves a sequence of sale transactions, that result in cash flows that can resemble a fixed deposit or a fixed-term loan.

The structure involves 3 or more parties and allows a customer to make a purchase of commodity in one currency, say US$, and then sell the same commodity to the bank on credit for a price in Euros. This price €1 = S1 + LIBOR. The bank would then sell the commodity for US$1.

The structure allows a customer to deposit in US$, and be paid back in €. The Islamic bank would have to hedge their positions in US$ to € to ensure the payment to the depositor in Euros would not be at a loss.