Retirement is a journey, rather than a destination, and in most economies, it is one that will become progressively longer as life-expectancy levels rise.

It is axiomatic that comfort and security should be priorities for all individuals undertaking this journey. For too many retirees, however, the journey is one that continues to be characterised by financial insecurity arising from insufficient savings to cover rising health-care costs and other day-to-day expenses. According to the New York Times, in the United States, “almost half of middle-class workers, 49%, will be poor or near poor in retirement.”

There are several drivers of increased financial anxiety among retirees, which are as applicable to the prosperous economies of the GCC as they are to Europe and the US. The first is that in an era of low inflation and interest rates, it is becoming increasingly challenging for retirees to generate a reasonable income from their investments. This is especially true for relatively low-risk savings vehicles such as bank deposits, money market funds and government bonds, where quantitative easing (QE) has in some cases pushed yields into negative territory.

Inadequate Long-term Financial Planning

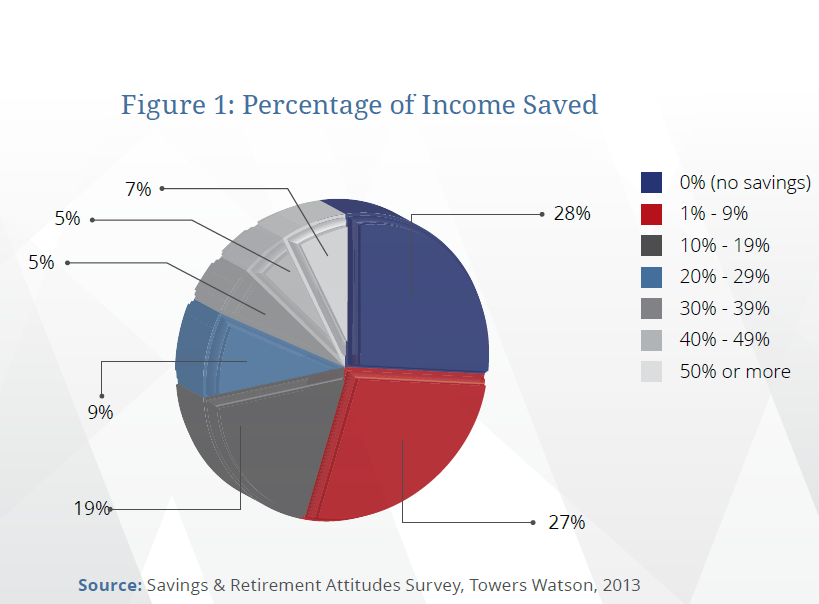

Another cause of heightened financial insecurity in retirement arises from poor long-term planning during professionals’ working lives, often twinned with unrealistic assumptions about the value of individuals’ savings. According to a Towers Watson survey published in 20132, savings rates among employees in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) are alarmingly low, with a quarter of survey respondents indicating that they save nothing at all, and more than half (55%) putting aside less than 10% of their income.

Towers Watson notes that these findings may be a reflection of the inclusion of Egypt and the Levant in the survey. “However, when we look at only the GCC countries we still see this pattern,” says the Towers Watson analysis. “Over a fifth do not save anything, and almost half save less than 10% of their earnings. This contradicts the impression that residents of the GCC save a significant proportion of their income and is surprising given the prolonged global economic uncertainty.”

Savings rates are higher among expatriates in the GCC, according to the Towers Watson data. But its survey still found that almost one in five (20%) expatriates save nothing at all.

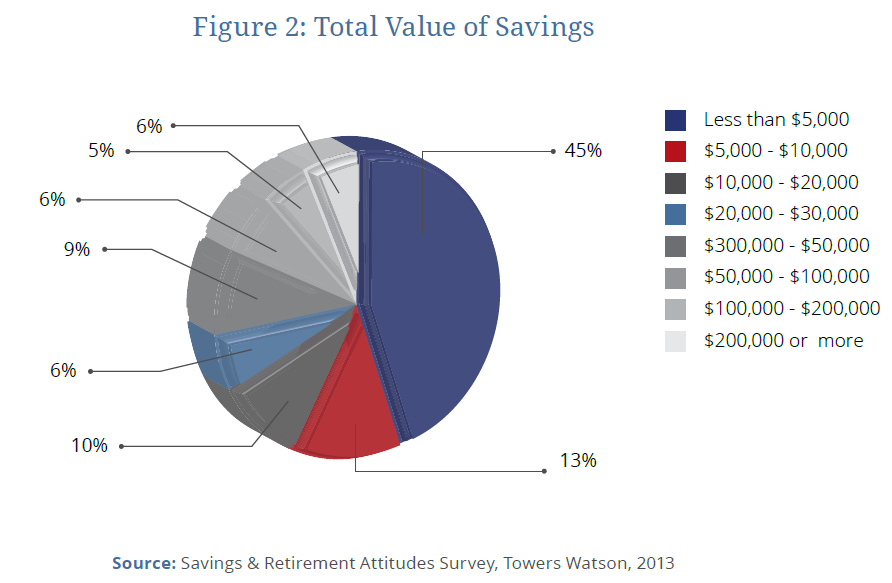

Among those in the GCC who do put aside a part of their income for retirement, the amounts saved are modest. According to the Towers Watson survey, 45% of respondents have savings of less than US$5,000, while 13% have between US$5,000 and US$10,000, and 10% have nest-eggs of between US$10,000 and US$20,000.

These private savings are inadequate to cover employees’ expectations of their retirement income. In its most recent UAE retirement survey3, HSBC found that on average, pre-retirees expect their retirement savings and investments (excluding pensions) to last for 12 years. “With pre-retirees expecting to fully retire at age 60 and a typical life expectancy in the UAE

of 76 years, there is a four-year ‘gap’ where they will be solely reliant on any state, employer or personal pension provisions they may have,” says the HSBC analysis.

Limited Incentives for Long-term Savers

A further, related driver of financial worries among the retired is inadequate provision of a retirement income by governments. Or it is a function of a legal and regulatory framework that fails to provide sufficient incentives for companies to provide for their employees, or for individuals to save for their retirement.

For expatriate workers in the GCC, which make up the bulk of the local labour force, retirement coverage from employers has traditionally been restricted to one-off payments when employees leave. Under the current UAE labour law, for example, which dates back three decades, employees are entitled to an end-of-service benefit (ESB) if they have completed one or more years of continuous service. The size of this benefit or gratuity varies, based on the length of service, and is linked to an employee’s basic salary but excludes non-salary items such as travel allowances and bonuses. On average, ESBs in the GCC equate to one month’s base salary for every year of employment.

A number of recent studies have suggested that these end-of-service benefits in the UAE, as well as the broader GCC, are inefficient and inadequate on a number of levels. Foremost among their inefficiencies is that they have historically been unfunded, which has left them vulnerable to cash flow shortages. Increasingly, companies are making more formal funding arrangements to cover ESB payments, although according to a recent Towers Watson survey, the vast majority of ESB programmes are unfunded.

Why End of Service Benefits are a Poor Relation to Pension Plans?

Even fully-funded end-of-service schemes, or those provided by employers with strong and dependable cash flows, can look unappealing to employees compared with secure long-term pension plans. Today, many companies in the GCC are responding to this by offering enhanced ESB schemes to employees as a means of attracting, retaining and rewarding the best talent. Nevertheless, according to a study published in February 2015 by Zurich International Life, the vast majority of employees in the UAE continue to regard the end-of-service benefit as an inadequate mechanism for saving for retirement.

Over 80% of the 1,000 UAE-based employees polled by Zurich International indicated that the final payment is not sufficient to cover the costs of retirement. The result is that many employees plan to use their ESB for other purposes, with 24% of the respondents to the Zurich survey saying they would reinvest the money as a deposit to buy a property. Others said they planned to use it to pay off debt (22%), settle school fees or other large bills (8%) or to splash out on a holiday or large luxury item (7%)5. Zurich says that it is a cause for concern that the majority of UAE employees appear to have no long-term retirement plans in place. It adds that the country’s population, and in particular its expatriate workforce, may be heading towards a “retirement funding time bomb” as a result.

Zurich’s conclusion is that there needs to be a significant shift in attitudes to promote a long-term savings culture in the UAE, and that employers can help to foster this cultural shift by encouraging employees to save for their retirement.

Demographic Pressures

This will be especially relevant for the economies of the GCC as demographic pressures start to build. Much of the economic success of the region in recent years has been built on the dynamic growth of the working age population in the 15-64 age bracket, which grew by 25% in the UAE and by more than 35% in Qatar between 2000 and 2015, according to Moody’s6. Today, all Gulf countries have a very low share of people classified as elderly (aged 65 or above) of just 0.5% of the population. This is projected to rise across the region over the next 15 years, reaching 7% in Saudi Arabia, for example, by 2030. While this is still very low compared with greying economies such as Japan, it will create added budgetary pressures and increase the need for individuals to make better provisions for their retirement.

Encouraging individuals to make larger and more realistic provision for their retirement will also become increasingly necessary as an ageing population makes more exacting demands on health services throughout the region. In a report published in 20077, McKinsey & Co forecast that the six members of the GCC would face “an unparalleled and unprecedented rise in demand for health care over the course of the next two decades.” McKinsey added that total healthcare spending in the region would rise from US$12 billion in 2009 to US$60 billion in 2025. “No other region in the world faces such rapid growth in demand with the simultaneous need to realign its health-care systems to be able to treat the disorders of affluence,” the report cautioned.

A number of countries in the MENA region have responded proactively to these anticipated pressures by introducing mandatory health care insurance initiatives. Abu Dhabi launched its new scheme in 2006, Qatar and Saudi Arabia amended their health insurance regimes in 2013, and Dubai’s mandatory health insurance law, which will cover all employees by 2016, came into effect in January 2014. As with the incentive of enhanced ESBs, companies throughout the region are increasingly recognising that there is a range of identifiable benefits to be derived from offering their employees more secure health insurance. According to a recent Towers Watson survey8, most firms in the region believe there is a “strong relationship between the provision of healthcare benefits and engagement, productivity and absenteeism.”

The Role of Pensions in National Development

Building a more attractive and sustainable savings environment has the potential to play a key role in national development in the GCC. On balance, the region has been very successful in recent years in creating a social and physical infrastructure as well as a legal and regulatory regime that is highly appealing to expatriate professionals. This is essential, given the Gulf’s reliance on expatriate labour, which, according to the latest HSBC expatriate report9, generally regards a move to the Middle East as a “short-term venture, not an opportunity to settle down.” This makes employers in the region more vulnerable to volatility and scarcity of the highest quality human resources than competing regions in Asia, Europe and North America.

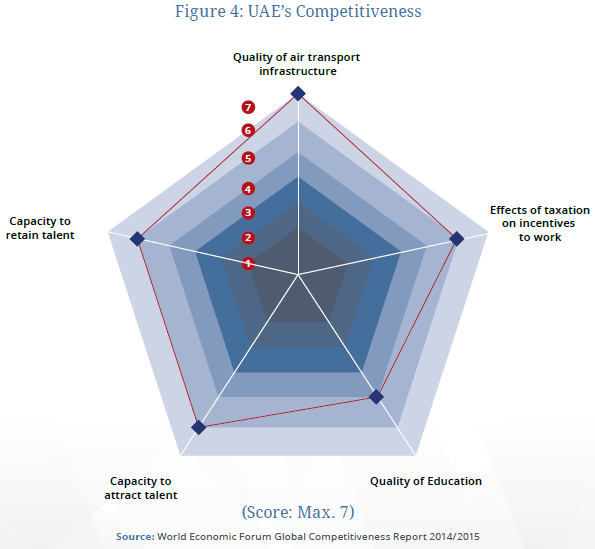

A number of indicators attest to the appeal of the Gulf in general, and the UAE in particular, for expatriate workers and their families. In the 2014-2015 World Economic Forum’s competitiveness index, the UAE leapfrogged countries such as Denmark, Canada and New Zealand to rank 12th, up from 19th the previous year. In the infrastructure ranking, meanwhile, the UAE is now third worldwide, with only Hong Kong and Singapore adjudged to have a more efficient infrastructure.

The UAE is now also placed 2nd for quality of air transport infrastructure, 9th for quality of education (ahead of Germany, Australia and the UK) and 3rd for the effects of taxation on incentives to work. For the time being, this gives the UAE a significant competitive advantage in recruiting the world’s best professionals: it ranks 3rd for the capacity to attract talent, and 6th for retaining talent.

The GCC’s capacity to attract and retain the best people is principally a reflection of the salaries paid in the region, which are in turn a reflection of the commodity-rich economic profile of the Gulf. GCC employers are also recognised for the generosity of the allowances and benefits they provide for their employees. The most recent GCC Allowances and Benefits survey undertaken by Aon Hewitt, based on an analysis of 90 companies throughout the region, found that children’s education allowances have increased “dramatically” in the Gulf, and are now as high as US$15,000 per child in Qatar and Kuwait. Qatar also leads the way in housing allowances, which have remained stable over the review period. According to the Aon Hewitt data, housing allowances range from US$25,000 to US$63,000 in Qatar, and are between US$23,000 and US$59,000 in UAE. On average, housing allowances equate to around 25% of basic pay in the GCC.

Beyond education and housing allowances, GCC employers also provide generous transportation and home leave benefits for their employees as well as their spouses and children, which are also regarded as essential for expatriate staff.

As Aon Hewitt comments in its report, it has yet to be seen if the recent decline in oil prices will lead to a fall either in salaries or additional allowances offered to employees in the GCC. For the time being, however, it is self-evident that the very generous remuneration and allowances packages offered by employers in the GCC have made an important contribution to the region’s economic success. More specifically, they have helped to underpin the rapid expansion of the region’s financial services industry.

The Importance of Pension Plans for Expatriates in the GCC

Many analysts believe, however, that if this success is to be sustained, countries such as the UAE will need to provide more durable, long-term pension provision for expatriates. In a report published in 200910, which is still applicable today, Booz & Co identified the absence of this provision as a potential stumbling block for the future expansion of the financial services industry in Dubai. Its analysis described pension systems in the GCC as “remarkably generous”, but cautioned that they were also “inherently unstable”. More specifically, the Booz report warned that “by not including foreign workers in their pension systems, the GCC countries…. miss a significant opportunity to strengthen their financial markets.”

Making formal pension schemes available to expatriates strengthens financial markets in several ways. As well as helping to attract and retain the best professionals, it is a sound way of ensuring that surplus liquidity is recycled in domestic capital markets, rather than remitted to the employee’s home country. This is especially relevant in economies such as those in the GCC that are overwhelmingly dependent on expatriates. In the UAE, for example, almost 90% of the eight million population are overseas workers11. It has been estimated that constraints of the local financial system leads the majority of these foreign workers to send up to half of their salaries home12. Unless these shortcomings are addressed, the volumes of remittances will increase, according to data published by the Dubai Statistics Centre. This forecasts that over the next few years, the number of UAE nationals is forecast to decline further, falling to just 5% of the population by 2020.

As long as the GCC could expect to depend on income from commodities, exploring ways of discouraging liquidity from being remitted overseas was not a priority. It is increasingly recognised throughout the region, however, that diminishing long-term

oil reserves will mean that economies will need to diversify away from commodities, which will call for the more efficient recycling of local liquidity. This is why Saudi Arabia, for one, has recently chosen to liberalise its capital market by allowing foreign institutions to invest in its stock market. As Barings commented in response to the news of the opening of the market, “the financial sector continues to grow in Saudi Arabia, [and] we will see increased use of pensions and mutual fund products as individuals save for retirement. A fully functioning equity market would clearly be beneficial for capital allocations and management of liabilities as well as estate planning.”

As the financial sector continues to grow in Saudi Arabia, it is expected to increase use of pensions and mutual fund products as individuals save for retirement. A fully functioning equity market would clearly be beneficial for capital allocations and management of liabilities as well as estate planning.

Innovations in the Market for Retirement Schemes in the UAE

To assist corporates with enhancing their employee retention, FWU partnered together with a leading licensed life takaful operator in the UAE and developed a “Defined Contribution” retirement savings plan; where both employers and employees can contribute. Innovative features include built-in life protection, Shari’a-compliant multi-manager investment strategies and a digital application allowing easy enrolment and account maintenance.

Another recent landmark for the development of retirement schemes for expatriates is the innovative Wealth Builder Plan by the National Bank of Abu Dhabi (NBAD) and RBC Corporate Employee and Executive Services (RBC cees). Launched in February 2013, this is the first pension and savings arrangement for expatriates to be operated by a UAE bank. According to RBC cees15, “the plan has been specifically designed for domestic and multinational companies which employ expatriates and are seeking to increase their return on human resources investment by attracting, rewarding and retaining skilled employees.”

“Typically,” cees adds, “UAE companies have found it hard to compete with developed markets to retain talent. In terms of remuneration and benefit packages, UAE companies generally have offered higher cash salaries rather than combining cash with share options or other long-term incentives. The Wealth Builder Plan looks to redress the balance and support a competitive total reward strategy.”

Employees, meanwhile, are offered the opportunity to save a significant part of their salary into a safe and secure product, and can withdraw 100% of their savings when they leave, because there are no minimum participation timescales. Additionally, employees have access to real-time, online valuations and can switch between investments at the click of a mouse.

The Growth of DC-based Pension Plans in the GCC

More broadly, many companies are already responding to the need to attract and retain talent by offering enhanced end-of-service benefits in the form of separate defined contribution (DC) pensions or savings plans. Towers Watson has been monitoring the growth of these supplemental plans for several years, publishing its Middle East End of Service Benefits Survey each year since 2010. “While there have been some fluctuations year on year, having run the survey for five years now, we see a steady trend of supplemental retirement or savings plans being made available to more employees,” notes the 2014 survey16. “The proportion of companies offering a DC plan to all employees has increased from 34% to 48% between 2010 and 2014, while fewer companies make a retirement or savings plan available only to certain employee groups.”

This increase will be welcomed by external consultants such as the World Bank, which in 2012 was reported to have recommended the establishment of pension funds for expatriate employees to the Dubai Department of Economic Development. Dubai has responded constructively to this proposal. Together with Deloitte, the Dubai Economic Council (DEC),

an advisory body established by the Government of Dubai, has recently drafted a report identifying a number of policy recommendations aimed at securing and enhancing Dubai’s sustainability and competitiveness17. These include the introduction of a state pension scheme for highly skilled expatriates, the extension of visa durations and a provision allowing some professionals to secure visas without a local sponsor.

A pension scheme modelled on the highly successful systems developed in the Far East, advises the Deloitte/DEC report, could result in expatriates staying in the Emirate longer and investing their savings locally rather than abroad. “Singapore and Hong Kong have introduced state pension schemes for expatriates with the aim of retaining human capital and savings within the country,” the report notes. “Hong Kong’s Mandatory Provident fund extends to expatriates who are given permission to work in Hong Kong for more than 13 months, while Singapore’s Central Provident fund extends only to expatriates with permanent residency.”

The DEC’s proposals to make the visa regime more flexible, according to the report, would encourage greater integration of expatriate professionals into the local economy. Extending visa durations to 10 years – versus two to three years today – would allow Dubai to follow in the footsteps of Singapore, says the Deloitte/DEC report, where “granting 10 year visas has positively influenced the consumption and investment decisions of the migrant population towards the domestic economy.”

For regional financial centres such as Dubai, the promotion of a more developed pension fund industry would also help to develop its credentials in asset management in general, and more specifically in the fast-evolving Islamic fund management sector. The establishment of a central provident fund modelled on the Singapore or Hong Kong template and managing its assets in accordance with Shari’a-compliant principles would represent an important step forward for Dubai’s financial services sector. One local fund manager has been quoted as saying that encouraging expatriates to invest in a Shari’a-compliant scheme would “multiply growth in assets under management”. “You could easily see 50 to 100 per cent growth [in] UAE,” this investor said.

The establishment of a central provident fund modelled on the Singapore or Hong Kong template and managing its assets in accordance with Shari’a-compliant principles would represent an important step forward for Dubai’s financial services sector.

Conclusion

Led by the UAE, the economies of the GCC have taken important steps in recent years towards creating more efficient retirement savings schemes for expatriates. However, more could be done to safeguard and support national development, and to foster deeper and more liquid capital markets, by providing expatriates with secure, long-term defined contribution pensions and savings schemes. A protracted period of low oil prices may be the incentive GCC governments require to accelerate the process of pension reform.