The decrease in articles in 2008 can be interpreted as a reduction in introductory articles written on Islamic finance, as more and more Japanese people have come to know of Islamic finance. In the last three years, more than ten books have been published on Islamic finance in the Japanese language. Although the authenticity of many of them is questionable, at least we can see that many publishers thought Islamic finance was a growing area of interest amongst the public.

Chronology of Japan-related Islamic finance

The decrease in articles in 2008 can be interpreted as a reduction in introductory articles written on Islamic finance, as more and more Japanese people have come to know of Islamic finance. In the last three years, more than ten books have been published on Islamic finance in the Japanese language. Although the authenticity of many of them is questionable, at least we can see that many publishers thought Islamic finance was a growing area of interest amongst the public.

Chronology of Japan-related Islamic finance

The beginning of Islamic finance in Japan is difficult to detect through the written medium, however, a book titled “Islamic Banking: Theory, Practice and Challenges” written by Fuad Abdullah Al-Omar & Mohammed Kayed Abdel-Haq in 1996, indicates that a Japanese bank, (Industrial Bank of Japan), was involved in Islamic trading in London in the 1980’s. Further, there were many Japanese firms engaged in Islamic transactions in London, emphasized by the many bankers, consultants at energy companies, and those at general trading firms, or Sougou Shousha, that were based in London in those days. However “Islamic finance” in those days mainly consisted of bay al iyna type of transactions. The “borrower” would buy a certain quantity of commodities such as oil and copper on a deferred payment basis, and sell them back to the seller, or “lender”, with spot payment made to the borrower. The price of the spot payment would be lower than that of the deferred one. This was considered Islamic; the differential on the surface taken as profit of trading goods, not as interest rate. This type of financial transaction is different from what we find in modern Islamic finance, in the sense that there was no screening by a Shari’a board, the players that offered credit were not necessarily financial institutions (but oil traders or similar background), i.e., it was not institutional.

The fact that some Japanese people had already en- gaged in Shari’a permissible trades helped the modern Islamic finance cause, when it came to be introduced to Japan as a new global phenomena in international finance. Along with the rise of the oil price, Islamic finance came to the scene in Japan around 2004-2005, and those with experience in Islamic transactions already had sense of it and explained it to other Japanese.

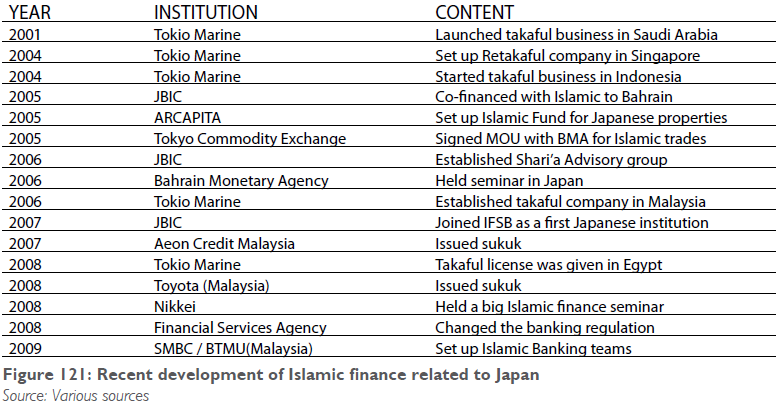

In the 1990’s, there were some Japanese asset management companies that offered Islamic fund products to Muslim investors mainly in the Middle East. Nomura Asset Management sold Al Nukhba Asia Equity Fund. DIAM, the then Daiichi-life IBJ Asset Management, offered Middle Eastern Fund for Japanese Equities. These products were screened by a Shari’a board, and in this sense, we can recognize these as Islamic in modern terms as well. Unlike today, this trend of selling Islamic products was only a regional phenomenon limited to the Middle East. Another rise in oil price will enable us to see Japan-related Islamic finance in the global context. Figure 121 shows recent developments and major events in Japan related to Islamic finance.

Details of recent legal amendments in Japan and its background

There has been a change in the Japanese banking regulation to accommodate Islamic banking-type transactions For this, a clause was added to the Ordinance for the enforcement of the Banking Act. The clause added in the Ordanance (17-3-2-2) is as follows (translated into English from Japanese);

“A transaction that is deemed equal to money lending, though it is not money lending (is included in the business domain of a bank’s subsidiary)”

This can be done if the following two conditions are met according to the clause;

“The transaction is the one that must not involve interest rate due to religious constraints.” and “The transaction should be authorized by those who have expertise in the religious discipline.”

Islamic lending is not considered as money lending, be- cause money lending would involve an interest rate by definition. Regarding “Those who have expertise in the religious discipline”, can refer to Shari’a scholars.

In order to fully understand the content of this amendment, it is necessary to know why this happened. In Japan, Islamic banking was considered to be a difficult proposition to be offered by a bank due to the existing banking act. Article 10 (Scope of Business) says that, “A Bank may conduct the following businesses:” followed by business offered by a bank such deposit and loans. Article 11 admits activities related to banking business Below is Article 12:

“A Bank may not conduct business other than the business conducted under the provisions of the preceding two Articles, and the business conducted pursuant to the provisions of the Secured Bonds Trust Act (Act No. 52 of 1905) or other laws.”

By this Article, an Islamic transaction that involves goods trading, such as those using murahaba, ijara, and istisna’ concepts, are considered to be out of the scope of a bank’s business.

As interest in Islamic finance grew steadily in 2006, there was a call from the financial industry to Islamic financial business, and this led to an amendment in the banking legislations.

This clause has raised some interesting points. Firstly, it stipulates the business domain of a bank’s subsidiary which includes Islamic-type products. Although the word “Islamic” is not explicitly mentioned, this is just to avoid the name of a specific religion. avoid the name of a specific religion.

Secondly, financial institutions other than banks are allowed to offer Islamic products. Asset management companies have sold Islamic equity funds, and a general insurance company has been engaged in the takaful business.

Thirdly, the business domain of other financial institutions is not mentioned in this clause, and hence, it was not made clear if, for example, what type of financial institutions should deal with Islamic products. This raises a question. Are sukuk dealt as bonds, or trust beneficiary rights? In the former, banks would not be permitted to do sukuk business, while they could handle sukuk if the latter interpretation would be considered.

Transactions by Japanese players

- Major examples of Japanese financial institutions offering Islamic business

After the legal amendment in December 2008, Japanese banks started to move in the Shari’a-compliant business. Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation Europe established an Islamic finance team and is offering Islamic services out of London. They hired some non-Japanese experts from European banks, to strengthen this business. Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ also set up a unit of Islamic banking in its Malaysian entity and is doing local business.

Mizuho Financial Group has not made institutional changes. However, Mizuho Corporate Bank has done a couple of Islamic transactions, including the arrangement of an Islamic syndicated loan in Saudi Arabia, to the Ma’aden Phosphate Project, through its Dutch subsidiary. The Group is in the process of establishing an Islamic capital markets business entity in Saudi Arabia. Securities firms have also shown some initiative. Nomura has started a team for Islamic structuring. Its asset management arm established a solely Islamic firm in Malaysia. Daiwa launched an Islamic ETF listed on Singapore Exchange. Both Nomura and Daiwa have dealt with sukuk underwriting out of their London-based offices.

- Examples of Japanese sukuk issuers and other users

Not only the sell side, but the buy side of financial services is also on the move. For example, there are a couple of Japanese corporations that have issued sukuk. Aeon Credit Service (Malaysia), a credit card and loan service provider, became the first Japanese entity to issue sukuk in 2007. The musharaka-backed sukuk was a MTN/CP program, denominated in Malaysian Ringitt. The sukuk proceedings are used for Islamic financing, including personal loans and motorcycle loans that are Shari’a-compliant.

Toyota is following this movement. Its subsidiary, (the then UMW Toyota), established a sukuk facility denominated in Malaysian Ringitt, also to finance their auto-loan business. The sukuk issuance by Japanese corporations thus far, has been primarily to bolster their local business, and not for a global business. There are more examples of Islamic borrowings. For example, Sumitomo Chemical’s joint project with Saudi Aramco and Petro Rabigh raised several billions of dollars. This project had several Islamic tranches.

- analysis: towards more Japan-related Islamic business

- Why Japan lacks a track record

Despite the growing interest in Islamic finance in Japan, and its economic position in the global context, it seems Japan has not yet substantially immersed itself with opportunities in the Islamic finance business. Other financial centers such as the UK, US, Singapore, Hong Kong, have substantial Islamic activities in their financial market. This could be down to three reasons: lack of appropriate knowledge, lack of networking, and geographical & historical shortcomings.

- Lack of appropriate knowledge

Although there is sizeable quantity of information, it seems the quality of information is not sufficiently authentic. Since Islamic finance was very new to the Japanese, a lot of wrong information was conveyed by those with only fragmentary knowledge. Consequently, Islamic finance was somewhat misunderstood among the people in the country. This implies that there is a big scope in the country for education business imparted by international experts.

- Lack of networking

Some professional Japanese bankers are already well-informed and ready to offer Islamic transactions in their respective business fields. However, even those players are not well involved in Islamic transactions. One of the reasons for this is the lack of communication with the Islamic finance community in the market, both with clients and with co-financiers.

The background for this is that generally the trend has been for Japanese financiers to offer financial services mainly to Japanese customers, even in the overseas markets. This situation is changing. The lack of contact points, or networks with Islamic communities, is considered to be another major reason for less developed Islamic business among the Japanese. This is a business opportunity for Islamic finance experts in the global markets. Japanese bankers will therefore be happy to welcome offers of collaboration in the Islamic business market.

Doing Islamic finance business with Japan

- Matrix

Below are some ideas of how Islamic finance can be applied to Japan-related transactions

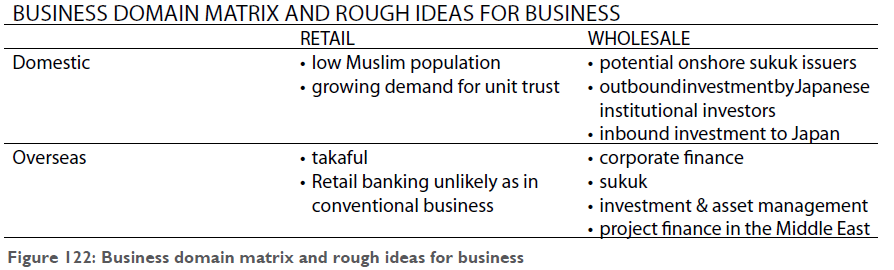

In order to clarify scopes of business, a 2×2 matrix composed of “retail-wholesale” axis and a “domestic-over- seas” market dimension as shown below.

According to the website “muslimpopulation.com”, the Muslim population in Japan is less than 0.2%. This means that demand for Islamic products thorough religious motivations is not likely to be substantial, and hence on this front, the need for banking, personal asset management, and insurance is not highly expected. Still, judging from the huge household financial assets, which amount to US$ 14 trillion, investment products such as unit trusts can be a good idea along with the trend that more individuals have come to invest in capital market products, not only deposits. Islamic products can be considered as an alternative investment product regardless of their religious nature. Islamic products can also be attractive to those who endorse socially responsible investment assets, because both have many commonalities, such as the screening of alcohol and tobacco-related equities.

The domestic-wholesale market has two main groups. One is the Japanese borrowers and investors that may utilize Islamic products. As previously mentioned, some Japanese firms have already raised funds in a Shari’a-compliant manner through their local entities. This may spread onshore, i.e., Japanese entities may issue sukuk. In order for this to be realized, appropriate legal, accounting and tax treatments are necessary. There is undoubtedly huge potential demand.

The other group is on the investors’ side. There are some Islamic investments from overseas in Japan. This is a good opportunity for Japanese institutional investors operating domestically, who are interested in holding Islamic assets, to assist these transactions.

The third area is the overseas-retail markets. The example of Tokio Marine, offering takaful products in Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, and Malaysia, is a good case in point. This field is, unlike domestic markets in Japan, full of potential given the existence of a huge Muslim population. Lastly: the wholesale business in overseas markets. This is the category with the biggest potential, given the fact that Japanese major banks and securities firms tend to focus on wholesale business, steering away from retail business that usually requires much higher initial cost. As shown before, Japanese banks and securities firms have the track records of Islamic wholesale transactions, which can be categorized to this area. Although Japanese financial institutions’ overseas business tends to target Japanese clients there, it is also true that Japanese financiers have come to explore local clients to expand overseas business.

Education and awareness among bankers

Japanese bankers have a basic understanding of Islamic finance, however, there is a strong potential opportunity for educational service providers to educate professionals in Japan on ethical and Islamic modes of financing.

Language is a difficult issue for education service providers. One solution would be to have alliances with other educational institutions. For example, Waseda Graduate School of Finance, Accounting and Law launched a class of Islamic finance in its regular curriculum since April 2008. The Graduate School held two seminars on Islamic finance, one jointly with the UK government in the presence of the Lord Mayor, and the other was co-organized with Kuwait University. Another useful channel to develop knowledge among people would be to introduce Islamic Finance Qualifications (IFQ) offered jointly by Securities and Investment Institute in UK and Banque du Liban. Although IFQ is not widely known in Japan, it would be another good way to improve people’s awareness.