Introducing derivatives

Derivatives are financial contracts – the inherent values of which are derived from, and exist by reference to, independently existing underlying(s). The underlying(s) for a derivative contract can be an asset or a pool of assets, an index or any other item to which the parties may choose to link their derivative contract. For example, credit derivatives, equity derivatives, index-linked derivatives and property derivatives are some of the popular types of derivative instruments. In addition to these, there can be ‘exotic’ derivatives instruments, such as inflation derivatives, weather derivatives and mortality derivatives.

The first record of organized trading in derivative instruments can be traced back to 17th century Japan. Feudal Japanese landlords would ship surplus rice to storage warehouses in the cities and then issue tickets promising future delivery of the rice at a specified price. These tickets (representing a rudimentary form of for- ward contract), which were traded on the Dojima rice market near Osaka, allowed landlords and merchants to lock the prices at which rice was bought and sold, consequently reducing the risk they faced.70

In the 19th century, Chicago was central to the development of derivatives in the United States. As in Japan, the seasonal nature of agricultural production was the main impetus behind the development of these financial instruments, culminating in the establishment of the Chicago Board of Trade in 1848. Other early exchanges involved in futures trading in the US included the New York Cotton Exchange (estd. 1870), and the New York Coffee Exchange (estd. 1885).

In terms of standardised documentation for derivative contracts, the formation of the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) in 1985 was a major milestone. In 1987, ISDA published the Interest Rate and Currency Exchange Agreement and the Interest Rate Swap Agreement, which were the first standardised derivative contracts to find wide acceptance globally. These were followed by the 1992 ISDA Master Agreement (Multicurrency – Cross Border) and the 1992 ISDA Master Agreement (Local Currency – Single Jurisdiction). The 2002 ISDA Master Agreement (Multicurrency-Cross Border) was ISDA’s response to market developments since 1992, and sought to consolidate the available market practice till that date. With the growing sophistication of derivative instruments, category specific standardised documents, such as the 2003 ISDA Credit Derivatives Definitions and related updates have been published by ISDA and have now gained wide acceptance.

Derivative instruments rely on specific embedded contracts to serve the required commercial ends. The most commonly used types of derivative contracts are forwards, futures, options and swaps, and these tend to be the building blocks for more complex derivative instruments. Derivatives can be either bilateral over-the-counter (OTC) instruments, or exchange-traded instruments (traded on exchanges such as NYSE Liffe, NASDAQ Dubai, Eurex or CME) and can be used for hedging (risk management), arbitrage and speculation.

(a) Use of conventional derivative instruments for risk management (hedging)

Risk management is the process of identifying, assessing and minimising risk in any commercial operation.

Banks, financial institutions, corporate houses and individuals face diverse risks in commercial operations including interest rate risk, currency risk and counterparty credit risk. The process of risk management aims to reduce (or, as the case may be, eliminate) risks by managing cash-flows efficiently, with a view to ensuring that there is no mismatch at any material point of time, between the cash-flows to an entity and the cash-flows from that entity.

Using conventional derivatives for risk management constitutes at least 10% of the OTC derivatives market, and can be illustrated by way of the following example. Let us assume that at the beginning of a crop season (e.g. 11 January 2009 (T1)), a wheat farmer (F) and a miller (M) enter into a contract whereby M agrees to buy and F agrees to sell 100 bushels of wheat at the price of £2 per bushel at the time of harvest (e.g. 11 June 2009 (T2)). By entering into this contract, both F and M have managed (hedged) their respective risks in the following manner:

- F knows (on T1) the price at which he will be able to sell the wheat (on T2) and can accordingly (i) make investments in fertilizers, seeds, etc.; and (ii) plan future profits; and

- M knows (on T1) what price he shall be able to buy wheat at (on T2) and can accordingly plan ahead in terms of pricing and marketing activities.

The contract described above is a basic example of a type of derivative contract known as a forward con- tract. If the same arrangement was mirrored through a clearing house or exchange (C) (whereby C buys the wheat from F and M buys the wheat from C), it would give rise to a futures contract. An exchange minimises the possibility of a default by either party by requiring the payment of an initial ‘margin’ and regular posting of the ‘margin’ based on marked to market calculations74. Through this process, losses are recognised as they oc- cur and the party which is out-of-the-money (i.e. the party with the losing position) is required to top-up its existing margin whenever a ‘margin call’ is made by C. Over the years, with increased sophistication among market-players, the concepts of ‘marked to market’ and ‘margin call’ have, along with other related concepts, evolved substantially.

Another type of derivative contract is the options con- tract. In the example above, if M paid a premium to F on T1 and acquired the right (but not the obligation) to buy 100 bushels of wheat at the price of £2 per bushel on T2, the contract would be regarded as an options contract whereby M has purchased a call option from

F. M’s decision whether or not to exercise the option on T2 would depend upon the spot price of wheat in the market on or about T2. For example, M would (i) exercise the option if the spot price was £2.50 on or about T2 (M’s option would then be regarded as being in-the-money); and (ii) not exercise the option if the spot price was £1.50 on or about T2 (M’s option would then be regarded as being out-of-the-money).

In the above example, M knows that he needs to pay £200 to F on T2. Let us assume that M’s income source is in US Dollars (US$). In such a situation, M might want to enter into a contract with a bank (B), whereby on T2,

(i) B agrees to pay M £200, and (ii) M agrees to pay B US$ 300. This would be a swap contract, by which M hedges its foreign exchange risk.

- Use of derivative instruments for arbitrage

Arbitrage is the practice of taking advantage of a price differential between two or more markets – i.e. striking a combination of matching deals that capitalize upon the imbalance, with the resulting profit being the difference between the market prices. Arbitrageurs closely follow the quoted prices of the same assets / instruments in different markets and if the prices are significantly divergent, to make a profit (taking into account any applicable transaction costs), enter into an arbitrage transaction whereby they buy the asset from the market having the lower quoted price and immediately thereafter, sell the same asset in the market where it has a higher quoted price.75 This type of use of derivative instruments requires substantial investments in global networking and telecommunication technologies, with a view to exploit potential arbitrage opportunities.

Arbitrageurs may also look to take advantage of a market situation where the current buying price of an asset is lower than the sale price of that asset in a futures contract. Unlike speculative transactions (described in paragraph (c) below), arbitrage transactions are not ‘zero sum games’ (as a gain by the arbitrageur is not directly linked to some other market player’s loss) and can be used to harmonise and regulate international prices.

- Use of derivative instruments for speculation

In the example in paragraph (a) above, M had a genuine trade interest guiding his decision to enter into derivative contracts. However, the same types of contracts (i.e. forwards, futures, options and swaps) can be entered into purely with an objective of making a speculative gain. For example, a speculator (X) can enter into a forward contract with F to purchase 100 bushels of wheat at £2 per bushel on T2. This would be based on X’s belief (fuelled by market intelligence and investment analysis) that the price of wheat will not be less than £2 per bushel on T2. On T2, (i) if the price of wheat is £1.50 per bushel, X pays £50 to F ((£2 – £1.50) x 100); or (ii) if the price of wheat is £2.50 per bushel, F pays £50 to X ((£2.50 – £2) x 100). Unlike derivative contracts for trade hedging purposes, in derivative instruments used for speculation, there is typically no actual delivery of goods (e.g. wheat, in the above example) from one party to the other, as participants in such contracts take market positions without taking off-setting positions under corresponding derivative contracts.

- Benefits of conventional derivative instruments

In today’s sophisticated global financial markets, derivative instruments can, if used prudently, contribute significantly to the welfare of all market participants in the following ways:76

- The use of derivative instruments for hedging purposes contributes to risk management and enables such users to formulate more accurate business plans by reducing uncertainties;

- Derivatives are crucially important to facilitate

price discovery, as futures market prices depend on a continuous flow of information from around the world and require a high degree of transparency. This flow of information reduces distortionary effects of government regulations and other externalities and facilitates the proper re-alignment of prices;

- Increased trading volumes lead to lower transaction costs, leading to an increased ‘value-for-money’ for market participants;

- Derivative instruments help to channelize more institutional money to emerging markets, as such instruments can be effectively used to manage market, credit and interest rate risks in underdeveloped local capital markets;

- The availability of derivatives increases liquidity in underlying cash markets, since market makers inject substantial liquidity into (i) the options and warrants markets; and (ii) the underlying stocks that they trade in; to hedge their market making activities in the derivative markets; and

- Since the returns generated from derivative in- struments are not correlated to more traditional instruments, derivatives contribute significantly to portfolio diversification and effective portfolio man- agement.

Islamic derivatives – introduction and legitimacy

Islamic derivatives are financial products which seek to generate a similar economic profile to comparable conventional derivative instruments, albeit through a Shari’a-compliant structure. Under Shari’a, all financial instruments and transactions must be free of at least the following five elements: (i) riba (interest), (ii) rishwah (corruption), (iii) maisir (gambling), (iv) gharar (unnecessary risk) and (v) jahl (ignorance). The prohibitions on interest and on taking ‘unnecessary’ risks become especially relevant in the context of derivative instruments.

In this context, it is important to note that while Shari’a prohibits riba, it does not prohibit trade or the making of profits as part of such trade(s). In fact, the Quran expressly alludes to the distinction between trade and riba in the following verse (2:275):

Those who eat riba do not stand except as stands one whom Shaytan has by the touch thrown into confusion. That is because they say: “Sale is like riba”. God has per- mitted trade and forbidden riba.

The prohibition on riba stems from the Shari’a tenet that money, by itself, should not be recognised as a commodity and consequently, there should be no re- ward for its use. Under Shari’a, money is perceived only as a medium of exchange and a unit of measurement. Islamic derivative products must therefore be based on underlying transactions in tangible commodities as opposed to merely superficial cash flows.

Furthermore, Shari’a-compliant financial instruments must adhere to daman – the principle of risk-sharing among all participants and the linking of risk to returns. In this regard, the widely held view is that one cannot profit from a venture in which one does not share the risk. Islamic derivatives therefore need to have an inherent risk-sharing mechanism in order to be Shari’a-compliant.

There is a wide spectrum of views on the legality of Islamic derivatives, ranging from the staunchly unfavourable to the vocally supportive. For example, Mufti Taqi Usmani of the Fiqh Academy of Jeddah argued (in 1996) that futures contracts are invalid under Shari’a because:

“Firstly, it is a well recognized principle of the Shari’a that purchase or sale cannot be effected for a future date. Therefore, all forward and futures contracts are invalid in Shari’a; secondly, because in most futures transactions de- livery of the commodities or their possession is not intended. In most cases the transactions end up with the settlement of the difference in price only, which is not allowed in the Shari’a.”

Conversely Fahim Khan states that:

“We should realize that even in the modern degenerated form of futures trading, some of the underlying basics concepts as well as some of the conditions for such trading are exactly the same as were laid down by the Prophet”

Further, Sheikh Nizam Yaquby is reported to have said (as reported in an article published in 2008):

“there are a few instruments which have been ‘tamed’ and designed to be alternatives (to) conventional derivatives. These are relatively new and we have to look into them.”

It could be argued that there is a general convergence of views for most Islamic derivative products, although there may also be divergences based on jurisdictions, madhabs and the perceptions of individual scholars.

A few Sharia tenets have, however, gained almost universal acceptance. These include the following:

- maslaha (i.e. the public good), towards which all commercial transactions should be geared (reduction in gharar is generally viewed as contributing to maslaha); and

- ibaha (i.e. permissiveness), which is generally taken to mean that if anything is not expressly prohibited un- der Sharia, it is deemed to be permitted.

In structuring Sharia-compliant products, one must therefore have regard, among other concepts, to daman, maslaha and ibaha.

- Key issues

Since the inception of Islamic derivatives, the lack of li- quidity in Islamic money markets and doubts regarding the credibility of such products (as a realistic alternative to conventional derivative products) have been the key issues relating thereto.

- Liquidity

The value of cash as a strategic asset is widely acknowledged in both the conventional and the Islamic finance industries. In a conventional banking system, the treasury manages the bank’s cash flow to maximise the profit-generating potential and to safeguard both the bank’s balance sheet and its profit-and-loss statement against liquidity risk. Conventional banks manage their excess liquidity mainly in four ways:

- lending any surplus in the inter-bank network,

- investing in government securities,

- lending to corporate customers, and

- keeping the excess funds at 0% return

Methods (i), (ii) and (iii) outlined above involve riba and hence, cannot be used by Islamic banks, while method

(iv) does not yield any return to the bank.

To resolve this dilemma, the International Islamic Financial Market (IIFM) launched the IIFM Master Agreement for Treasury Placement (MATP) in October 2008, which enables financial institutions globally to enter into OTC commodity murabaha transactions. The MATP documentation covers the following two separate structures:

- where the depositor/client acts as buying agent (either disclosed or undisclosed) of the financial institution; and

- where the depositor/client and financial institution act as principals with no agency relationship

The MATP documentation consists of a master Mu- rabaha agreement, a master agency agreement and a commodity purchase letter of understanding,80 and has already been widely used in several jurisdictions such as the GCC region, Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur and Singapore. Even outside the MATP framework, commodity mura- baha is currently the most widely used product in the Islamic money market and is used by several financial institutions (particularly in the GCC region) to manage their liquidity risk81. Further development of the global Islamic money market will help banks manage their li- quidity risks more efficiently.82

(b) Credibility

For the development of the Islamic finance industry, Shari’a-compliant financing techniques must be regarded as credible alternatives to their conventional counterparts. The lack of a central regulatory body, divergent views relating to the same product/financing technique aired by different Shari’a scholars and the general practice of not disclosing fatwa (for OTC derivatives only) leading to reduced transparency in the market could hamper the credibility of Shari’a– compliant products. Similar to the issues highlighted in the Turner Report (relating to the conventional finance sector), a more uniform approach, greater transparency and stronger regulation are also necessary prerequisites for the sustainable growth of Islamic finance.

Recently, the Malaysian legislature passed the Bank Negara Malaysia Bill 2009, under which decisions of the Islamic Finance Syariah Advisory Council (the Council) will be binding on the court which referred the relevant matter to the Council.83 In another recent development, the UK Budget 2009 (the Budget) provides relief from stamp duty land tax in respect of transactions under- taken as part of the issue of alternative finance prop- erty investment bonds.84 Along with other favourable provisions in the Budget, this provision places Islamic financing structures such as the sukuk on a level playing field (from a tax treatment perspective) as compared to conventional bonds. The above initiatives serve as good examples of concrete legislative/regulatory measure which should lead to greater uniformity and renewed investor confidence in Shari’a-compliant products, resulting in a boost to the credibility of such products.

The global development of Islamic finance

Over the past 30 years, Islamic finance has expanded to become a distinctive and fast-growing segment of the international banking and capital markets today. The origins of modern Islamic finance can possibly be traced to a savings bank based on profit-sharing established by Ahmed Elnaggar in the Egyptian town of Mit Ghamr in 1963.85 In 1972, the Mit Ghamr Savings project became a part of the Nasr Social Bank which still continues in business in Egypt. Subsequently, in the 1970s, oil-related wealth provided the capital resources for the establishment of several Islamic banks – notably the Islamic Development Bank (1974), the Dubai Islamic Bank (1975), the Kuwait Finance House (1977), the Faisal Islamic Bank of Egypt (1977) and the Bahrain Islamic Bank (1979).86

In the 1990s, HSBC and Citigroup established global Islamic finance divisions. These banks started out offering primarily a few mutual funds to suit Sharia investors. Today, both the Islamic finance divisions of conventional banks and stand-alone Islamic banks are creating instruments that parallel many of the Western world’s financial products, from consumer loans to bonds. With the passage of time and the global development of Islamic finance, investors’ appetite for complex Islamic products has also grown significantly and market players predict that there is strong potential for further growth in Islamic derivatives.

- Key jurisdictions

- Malaysia

Over the past decade, Malaysia has made a concerted effort to promote itself as an Islamic finance hub. It is presently (i) the world’s largest Islamic banking and financial market, with Islamic banking assets totalling US$ 30.9 billion and (ii) the world’s largest Islamic private domestic market in debt securities, estimated at approximately US$ 34 billion. Malaysia also has a critical mass of market players in the Islamic finance industry and an active Islamic money market which channels approximately RM 30 billion monthly. The above factors, combined with the growing popularity of the Labuan International Offshore Financial Centre located just off the Malaysian coast, make Malaysia an inviting choice for prospective investors in Islamic finance.

- The Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC) countries

Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Oman together constitute the GCC. The historical linkage of Islamic finance to oil-related wealth continues to be important even today, with the DIFC being a major Islamic finance hub in the region. Related initiatives, which are currently in various stages of implementation, include setting up the DIFC Shari’a Centre, an Islamic hedge funds platform, an Islamic finance portal, a commodity murabaha exchange and the creation of a judicial academy and research centre.90 The presence of the head offices of many Islamic banks in the GCC region contributes significantly to its importance as a principal driver in Islamic finance.

The building blocks – key Concepts Used In Islamic Derivatives Structures

There are a number of key traditional Islamic products that can be used to create the building blocks of Islamic derivatives – i.e. murabaha, wa’ad, arbun and salam.

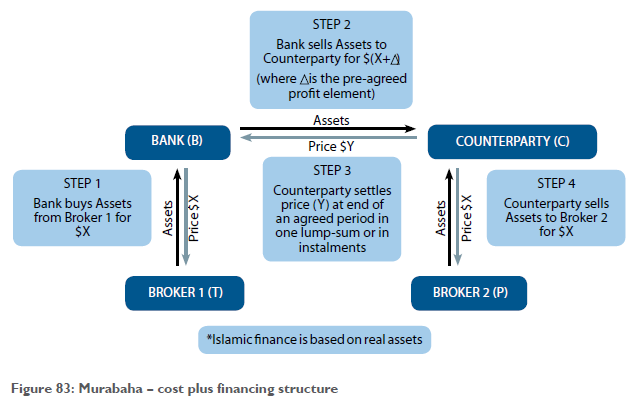

- Murahaba

Murabaha (also known as cost-plus financing) is a particular type of Shari’a compliant financing technique, which forms the foundation of almost 70% of all Islamic derivative products. Under such a structure, typically the bank (B) (i) purchases commodities from a third party broker, Broker 1 (T) at a particular price (X) (Step 1) and (ii) on-sells these commodities to the counterparty

(C) at a price which includes B’s cost price (X) and some profit / mark-up (Δ), which B discloses to C. Thus, C’s cost price is equal to X plus Δ (Y) (Step 2).

Typically, Y is payable by C in instalments, but it can also be paid as a one-time bullet payment on a specified date in the future (similar to the ‘sale and deferred payment’ model in conventional financing) (Step 3). Having purchased the commodities from B, C on-sells these to another third-party broker, Broker 2 (P) at a price equal to X (Step 4).

The above structure is Shari’a compliant because (i) no interest is being charged by B (rather, B is making a profit, which is justifiable since B bears the risk, for however short a period, of not being able to on-sell the commodities to C); and (ii) the financial transaction is backed by underlying transactions in tangible goods. It is important to maintain the severance between the following three parts of a murabaha as separate transactions:

- the purchase of goods by B from T;

- the sale of goods by B to C; and

- the sale of goods by C to P.

Murabaha is a particularly popular as a financing technique in the realms of consumer finance and asset finance. Notably, murabaha can also be used in a Shari’a-compliant profit-rate swap and/or a cross-currency swap (see Sections 14.5.2 and 14.5.1 below).

- Wa’ad

Wa’ad is a traditional Islamic product which, in the context of commercial dealings, is generally accepted to mean that of a unilateral promise.91 According to a fatwa issued by the Islamic Fiqh Academy (the IFA) at its Fifth Conference held in Kuwait (1988-1989), a wa’ad, in the context of a classic murabaha sale is morally bind- ing, and additionally, its fulfilment may be enforceable at court, if: (a) the promise is a unilateral promise binding only one of the parties to the murabaha; and (b) the promise has caused the promisee to incur some liabilities. Since then, this view has attracted widespread scholarly support.93 It is however debatable whether the IFA’s fatwa extends to Islamic finance structures other than murabaha-related wa’ad transactions. The Accounting and Auditing Organization of Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) has endorsed the extension of the IFA fatwa to currency exchange transactions within an Islamic framework,94 thereby suggesting that the application of wa’ad may not need be confined to the classic murabaha model. However, such extension of the IFA’s fatwa has been criticized by certain authors.

Since the wa’ad is a unilateral promise, it does not have to satisfy the requirements of a bilateral contract (aq’d) under Shari’a (i.e. (i) knowledge of the price and (ii) possession or ownership of the subject matter of the contract). This inherent flexibility of the wa’ad renders it particularly helpful in developing several innovative Shari’a-compliant structures, such as an FX option (refer: Section 14.5.1 below) or a total return swap (see Section 14.5.4 below).

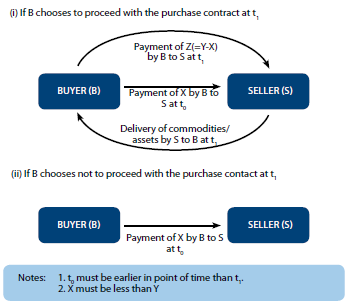

- Arbun

Arbun (literally translating into ‘earnest money contract’) is a conditional purchase contract, which is permissible under Shari’a. Under an arbun contract, the buyer (B) concludes a purchase and makes an advance of some sum (X) which is less than the purchase price (Y) to the seller (S). The contract stipulates that if B decides to proceed with the transaction, he will pay S the purchase price minus the initial deposit (Y minus X = Z). If B decides not to proceed with the transaction, he forfeits the deposit in favour of S.

Arbun offers a close analogy to a conventional option, although it cannot be regarded as identical to an option (because, unlike an arbun contract, the premium paid under a conventional option is not deducted from the purchase price if the buyer chooses to exercise the option).

Several madhabs declare arbun to be a void contract, since it makes a gift (the initial deposit) conditional upon a sale, and therefore allegedly offends the Shari’a principle of non-combination of gratuitous contracts with onerous ones. However, the Hanbali school accepts the arbun as a valid form of contract, based upon hadith.96 The OIC Academy has also endorsed arbun, but only if a time limit is specified for exercising the option.97

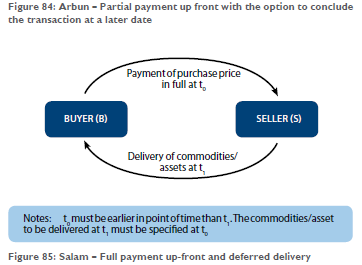

- Salam

Salam (also known as bai salam) is similar to a conventional forward contract whereby the price of an asset is paid up-front at the time of the contract, for the asset to be delivered later (similar to a ‘deferred delivery’ model in conventional finance).

The legitimacy of salam is rooted in the sunna, whereby the Prophet Muhammad is believed to have observed the practice of people paying in advance the price of dates to be delivered within one, two or three years in Madina. The sale, however, did not specify the quality, measure or weight of the dates at the start of the contract. The Prophet Muhammad ordained that:

“Whoever pays money in advance (for fruits) (to be de- livered later) should pay it for a known quality, specified measure and weight (of dates or fruit) along with the price and time of delivery” (reported by Imam Bukhari and others)

Consequently, when using salam in structuring today, scholars prescribe several strict conditions, including the following:

(a) the seller must undertake to supply a specific asset at a future date in exchange for full spot payment (in advance) at the start of the contract;

- before delivery of the asset, the risks on the asset lies with the seller and upon delivery, the risks are transferred to the buyer; and

- the buyer can enter into a similar contract with a third party in a parallel salam. This parallel contract would be independent of the first salam contract.

While writers such as Mohammed Obaidullah have preferred concepts such as khiyar al-shart (option as a stipulated condition), khiyar al-ayb (option to reject an object based on a defect therein), khiyar al-ruyat (option after inspection) and khiyar al-tayeen (option of determination or choice), these are relatively complicated products that are yet to be fully synchronised with conventional financing.

The salam is a popular technique for generating working capital. It can also be used in a Shari’a-compliant structure which mirrors the cash-flows generated by a conventional short-selling structure.

Shari’a-compliant derivative products

In this section, we analyse several products such as Shari’a-compliant cross–currency swaps, profit rate swaps and FX options that are commonly used in the Islamic derivatives markets. We also discuss how these products use the building blocks of murabaha, wa’ad, arbun and salam, as discussed above.

- Cross-currency swap

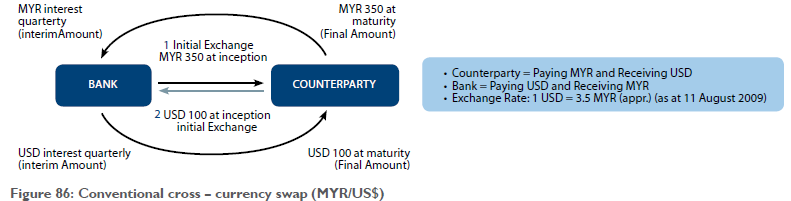

(a) Structure and cash-flows in a conventional cross-currency swap

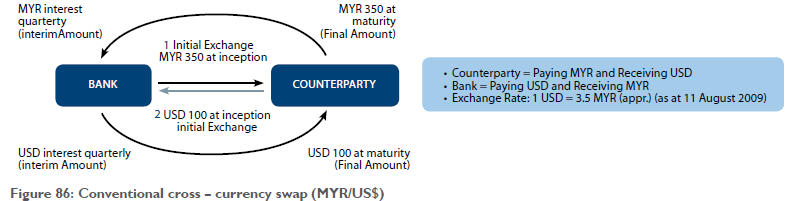

A conventional cross-currency swap usually consists of three stages: (i) a spot exchange of principal at the outset (Initial Exchange), (ii) a continuing exchange of interest payments during the swap’s life (essentially a series of FX forward trades) (Interim Amounts) and (iii) a re-exchange of principal at the maturity of the contract (normally at the same spot rates as those used at the start) (Final Amount). Clearly, the prohibitions on riba, maisir and gharar would render such a structure untenable under Shari’a.

Cross-currency swap

B) Structure and cash-flows in a Shari’a-compliant cross-currency swap

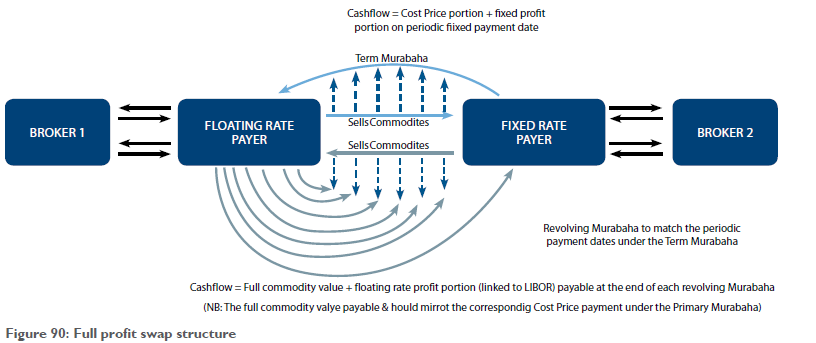

The challenge, therefore, is to generate cash flows which are similar to a conventional currency swap, but within a Shari’a-compliant framework. To this end, one can use reciprocal murabaha transactions, whereby the parties enter into murabaha contracts (a Primary (Term) Murabaha and a Secondary (Reverse) Murabaha) to sell Shari’a-compliant assets (often London Metal Exchange traded metals, such as palladium and aluminium) to each other for immediate delivery but on deferred payment terms.

(i) The Primary (Term) Murabaha

Under this transaction the Bank (i) sources commodities from a commodity broker (Broker A) at Cost Price (step 1, in the diagram below); and (ii) on-sells these commodities to the swap counterparty (the Counterparty) (step 2). The value of commodities bought and on-sold (in steps 1 and 2 respectively) are both denominated in Currency A (MYR).

Payment by the Counterparty for the commodities purchased under the Primary Murabaha is on a deferred basis, in instalments payable on pre-agreed payment dates (each a Deferred Payment Date). Each instalment represents a portion of the pre-agreed profit element, with the exception of the final instalment, which also includes payment in full of the Cost Price.

The commodities are delivered on the date on which the transaction is entered into. On receipt of the commodities, the Counterparty (or its agent) promptly on- sells the commodities to a different commodity broker (Broker B) to generate a Currency B (US$) payment (steps 3 and 4).

- The Secondary (Reverse) Murabaha

To initiate the Secondary Murabaha, the Counterparty

(i) purchases commodities from Broker B and makes payment in Currency B (step 5), and (ii) immediately on-sells these commodities to the Bank for immediate delivery (step 6). The commodities sold under the Secondary Murabaha should have the same value as those purchased under the Primary Murabaha (the Currency B equivalent of the Cost Price being the Relevant Amount, in the diagram below).

Payment by the Bank is on a deferred basis in instalments in Currency B, such instalments to represent a portion of the pre-agreed Secondary Murabaha profit element (with the exception of the final instalment, which also includes payment in full of the Currency B equivalent of the Cost Price). Instalment payment dates under the Secondary Murabaha mirror those under the Primary Murabaha (i.e. on each Deferred Payment Date, a payment shall be due (i) from the Bank to the Coun- terparty in Currency B; and (ii) from the Counterparty to the Bank in Currency A). Upon receipt of the commodities the Bank immediately on-sells these to Broker A (step 7) to generate a Currency A payment.

(c) Industry Usage

In October 2006, Citigroup designed a currency swap for the Dubai Investment Group (DIB) to hedge the currency risk on DIB’s RM 828 million (approximately £119 million) investment in Bank Islam Malaysia.101 Standard Chartered Saadiq, Al Hilal Bank and Calyon also market products based on Shari’a-compliant cross-currency swaps.102

- Profit Rate swap

- Structure and Cash-flows

A profit rate swap is best analogised to a conventional interest rate swap, under which the parties agree to exchange periodic fixed and floating payments by reference to a pre-agreed notional amount. As with many conventional derivative products, a conventional interest rate swap is problematic from a Shari’a perspective as it potentially contravenes the Shari’a prohibitions on riba, maisir and gharar.

The profit rate swap seeks to achieve Shari’a compliance by using reciprocal murabaha transactions (similar in some respects to the structure used for a cross-currency swap, as discussed above). A term murabaha is used to generate fixed payments (comprising both a cost price and a fixed profit element) and a series of corresponding reverse murabaha contracts are used to generate the floating leg payments (the cost price element under each of these reverse murabaha contracts is fixed but the profit element is floating).103

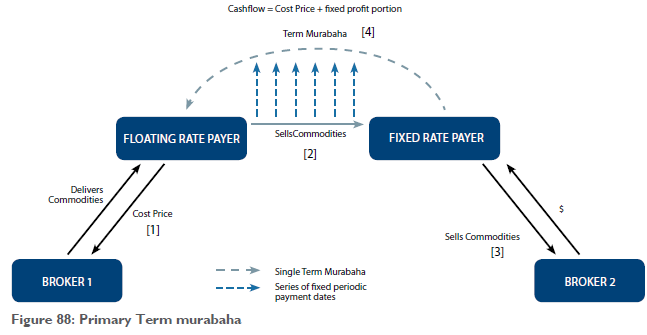

- The Primary (Term) Murabaha

The process is initiated by the floating rate payer (the Floating Rate Payer) (i) sourcing commodities from a commodity broker (Broker 1) (step 1, in the diagram below); and (ii) on-selling these commodities to the swap counterparty (the Fixed Rate Payer) (step 2). The value of commodities bought and on-sold is the preagreed Cost Price for the transaction and the commodities are delivered on the date on which the transaction is entered into.

On receipt of the commodities purchased, the Fixed Rate Payer (or its agent) on-sells those commodities immediately to a different commodity broker (Broker 2) (step 3) to generate cash. The Fixed Rate Payer pays for the commodities purchased under the Term Murabaha on a deferred basis, in instalments payable on a series of pre-agreed payment dates (each a Deferred Payment Date) (step 4). Each instalment comprises both a Cost Price element (a repayment of a set percentage of the Cost Price) and a fixed profit portion (paying a portion of the Floating Rate Payer’s profit on the transaction).

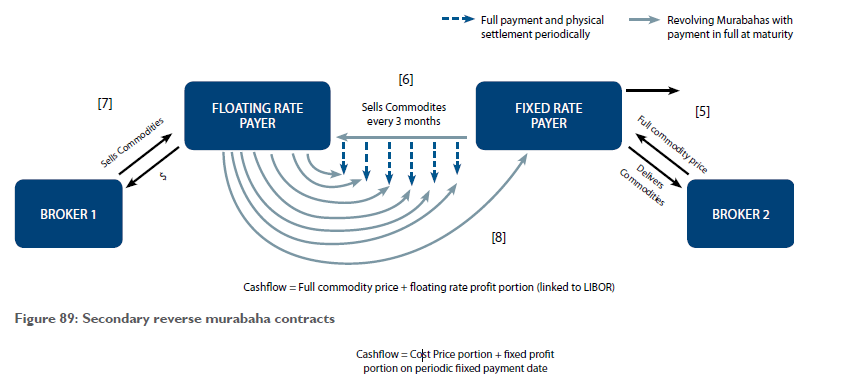

- The series of sequential Secondary Reverse Mura-baha Contracts (SRMCs)

An agreement by which the Floating Rate Payer simply agrees to pay a variable amount (linked, for example, to LIBOR) to the Fixed Rate Payer on certain pre-specified dates would not be Shari’a-compliant due to the uncertainty (gharar) associated with such a structure. SRMCs help us resolve this problem, as each floating rate payment is linked to an underlying purchase and sale of commodities.

The first SRMC (SRMC1) is entered into on the date of entry into the Primary Murabaha transaction and is initiated by the Fixed Rate Payer purchasing commodities from Broker 2 (step 5, in the diagram below). For the purpose of SRMC1, the Fixed Rate Payer uses only that portion of the Cost Price which is due to be repaid to it on the first Deferred Payment Date as capital for purchasing commodities from its broker.

The Fixed Rate Payer immediately on-sells these commodities to the Floating Rate Payer for immediate delivery (step 6), and the Floating Rate Payer immediately on-sells such commodities to Broker 1 (step 7) to generate cash. Payment by the Floating Rate Payer is on a deferred basis by a single bullet payment comprising

(i) the full value of the commodities purchased under the relevant SRMC plus (ii) the Fixed Rate Payer’s profit (such profit being calculated by reference to a floating rate formula (e.g. linked to LIBOR) and thus generating the floating rate element) (step 8). Each such payment is due on the next Deferred Payment Date under the Priary Murabaha (at a frequency of every three months, in the illustrative diagram below).

- Industry Usage

In October 2006, Standard Chartered Saadiq entered into a US$ 150 million three-year profit rate swap with Kuwait-based Aref Investment Group S.A.K. Commenting on the deal, Dr. Ali Al Zumai, Chairman and Managing Director of Kuwait-based Aref Investment, said:

“The swap is a significant development in broadening capital market instruments. It gives us the flexibility to hedge through a Shari’a-compliant solution.”

BNP Paribas, Al Hilal Bank and Calyon have also developed products based on Shari’a-compliant profit rate swaps.

Figure 89: Secondary reverse murabaha contracts

- FX Option

- Structure and Cash-flows

A conventional option gives the buyer of the option the right, but not the obligation, to enter into a certain transaction (i) on a future date (European option), or (ii) on any of certain specified future dates (Bermudan option), or (iii) within a specified period, till the expiration of the option (American option).

The wa’ad can be used to structure a Shari’a-compliant FX (i.e. currency) option. In this regard, Shari’a distinguishes between the creation of an option and the trading of an option. The creation of an option (and the subsequent exercise or cancellation of the same) for genuine trade hedging purposes is broadly viewed as permissible, as it reduces gharar and is therefore regarded as contributing towards maslaha.106 However, the trading of an option without any accompanying purchase/sale of underlying tangibles, undertaken solely with the objective of making a speculative gain (akin to gambling, i.e. maisir, which is prohibited under Shari’a), is regarded as impermissible by several Shari’a scholars, as this is looked upon as increasing gharar.

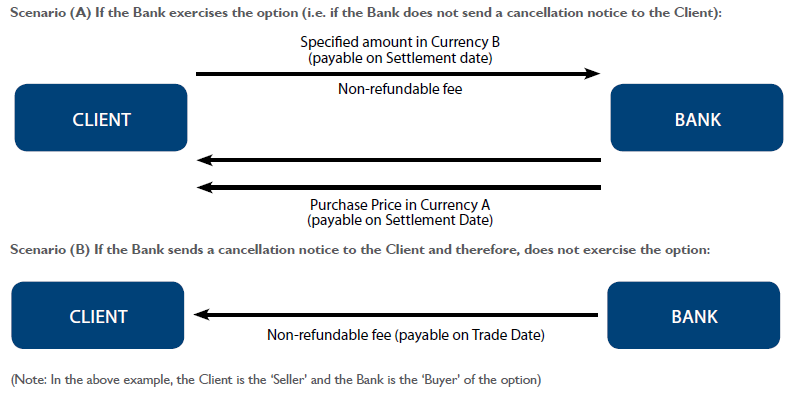

Under one application of this structure, (i) the Client promises the Bank (the date of such promise being the Trade Date) to sell a particular amount of a currency (Currency B) against another currency (Currency A) on a pre-determined date (Settlement Date) and at a predetermined rate; (ii) the Bank acknowledges the Client’s promise but makes no promise to the Client; and (iii) the Bank pays a non-refundable fee (premium) to the Client, regardless of whether the Bank chooses to exercise the call option by enforcing the wa’ad (the Bank’s decision whether or not to exercise the option being dependent upon whether the option is in-the-money on or about the Settlement Date). The Bank, therefore, has a right to accept the promise (and thereby exercise the wa’ad-based option) or cancel the promise by sending a cancellation notice.

In the context of a similar wa’ad-based FX option developed by a multinational bank, the relevant Shari’a Board stated that the concerned product is “for hedging or cost reduction purposes only and not for speculation”.

Cash-flows

- Industry Usage

In February 2009, the Gulf Finance House (GFH) announced a partnership with Deutsche Bank in a first-of-its-kind foreign exchange hedging deal worth over Euro 30 million (US$ 39.4 million). The deal utilises a Shari’a– compliant FX-option developed by Deutsche Bank and approved (for the purposes of the above deal) by the Secretary-General and member of GFH Shari’a Board, Dr. Fareed Hadi. Commenting on the deal, Mr. Abdul Rahman Al Jasmi, Deputy Chief Executive Officer, GFH said:

“We are proud to be the first bank to utilize the Islamic FX Option provided by Deutsche Bank. This pioneering product will help GFH to eliminate foreign exchange risks and as such we are pleased to be able to add this type of promissory note or option to our inventory of risk management tools.”(emphasis supplied).

Calyon, Al Hilal Bank and the State Bank of Pakistan have also developed products based on Shari’a-compliant options.

- Total Return Swap

(a) Structure and Cash-flows

The underlying economic reasons for entering into a conventional total return swap are that, (i) it allows investors to gain exposure to an asset which it does not necessarily need to hold on its balance sheet, and (ii) pay-offs can be structured so that the other party can hedge against the upside or downside related to that particular asset or class of assets. Under Shari’a, a similar economic profile can be generated by using a double wa’ad structure.

Scenario (A) If the Bank exercises the option (i.e. if the Bank does not send a cancellation notice to the Client):

Under this structure, an SPV Issuer issues Certificates to investors in return for the issue price (steps 1 and 2, in the diagram below). The Issuer then uses the issue price to acquire a pool of Shari’a-compliant assets from the market (Shari’a-compliant Assets) (steps 3 and 4). These Shari’a-compliant Assets could, for example, be shares listed on the Dow Jones Islamic Market Indexes (DJIMI).

The investors (holders of the Certificates) gain exposure to an underlying index or assets (the Underlying) based on two mutually exclusive wa’ads between the Issuer and the Bank. Under one wa’ad (Wa’ad 1), the Issuer promises to sell the Shari’a-compliant Assets to the Bank at a particular price (which is linked to the performance of the Underlying) (Wa’ad Sale Price) (step 5), while under the other wa’ad (Wa’ad 2), the Bank promises to buy the Shari’a-compliant Assets from the Issuer at the Wa’ad Sale Price (step 6). Out of these two wa’ads, only one shall ever be enforced.

(Numbers in the diagram above denote chronology of events. Either 5 or 6 will occur (but never both, as explained above)).

At maturity, the Bank will calculate how the Shari’a-com- pliant Assets have performed relative to the Underlying, and (i) if the Wa’ad Sale Price is greater than the market value of the Shari’a-compliant Assets, then the Issuer shall enforce Wa’ad 2 (similar to a conventional put option), or (ii) if the Wa’ad Sale Price is less than the market value of the Shari’a-compliant Assets, then the Bank shall enforce Wa’ad 1 (similar to a conventional call option).

The commercial significance of this structure lies in the fact that, similar to a conventional total return swap, it offers Islamic investors the opportunity to potentially swap the returns in one basket (as generated from the Shari’a-compliant Assets) with the returns in another basket (the Wa’ad Sale Price, as calculated with reference to the Underlying).

The total return swap mechanism has been criticised by Sheikh Yusuf Talal DeLorenzo (a prominent Shari’a scholar) on the basis that it was devised with a view to “wrap up a non-Shari’a compliant underlying into a Shari’a compliant structure.” Sheikh de Lorenzo argues that such a structure is not Shari’a compliant because:

- the returns, under such structures (overall, termed ‘Shari’a Conversion Technology’), are determined by the performance of funds which are not Shari’a-com- pliant and which could invest in haraam securities;

a qiya (analogy) cannot be drawn between the use of LIBOR for pricing (which is generally considered to be permissible) and the use of the performance of non-Shari’a-compliant assets for pricing; since while the former is used to indicate the return, the latter is used to deliver the return; and

the cash-flows in a total return swap based on a double wa’ad indicate that the investment by an Islamic investor operates as a trigger for a series of transactions which are not necessarily Shari’a-compliant.

However, Hussein Hassan, Head of Islamic finance and structuring for the Middle East and North Africa at Deutsche Bank, claims that in the Deutsche Bank structure using the double wa’ad mechanism, Deutsche Bank kept Islamic investors’ investments isolated from haram assets, as demonstrated by the Shari’a audits carried ou by the bank. It is further argued by supporters of the double wa’ad structure that the use of the Underlying as a point of reference is no different from issuing a Sukuk benchmarked against LIBOR.

- Industry Usage

The double wa’ad structure has been used by Deutsche Bank in relation to a total return swap. This derivative product was approved by the Shari’a Board of Dar Al Istithmar (Shari’a Advisor to Deutsche Bank), consist- ing of five of the world’s leading Shari’a scholars: Dr. Hussein Hamed Hassan, Dr. Ali AlQaradaghi, Dr. Abdul Sattar Abu Ghuddah, Dr. Mohamed Ali Elgari and Dr. Mohamed Daud Bakar. According to Hussein Hassan, “Driven by investor demand, the technique has been instrumental in opening up investment in asset classes that have previously been closed to Islamic investors”.

- Short-selling

Conventional short-selling involves selling a borrowed security (generally a stock or a share) that the seller does not own. There is, therefore, a separation of ownership and risk in any conventional short-selling mechanism. The short-seller essentially takes a chance on the security in question decreasing in value, which would enable the short-seller to buy that security back from the market at a later date (for a lower price) and make a speculative gain in the process.

Under Shari’a, according to Hadith, one cannot sell what one does not own and ownership cannot be divorced from risk. The arbun or the salam can be used to emulate the economics of a conventional short-sale in a Shari’a-compliant structure, whereby the seller actually owns the securities which form the basis of the transaction.

Our understanding in this regard is based solely on publicly available materials, although it is not implausible that such Shari’a-compliant structures incorporate the creation of alpha, to ensure that the returns are synonymous with a conventional short-selling arrangement.

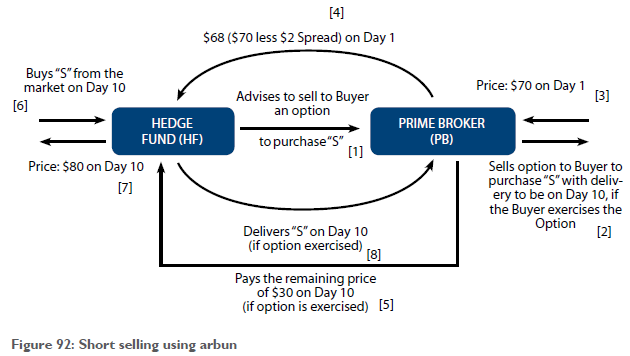

- Short-selling using arbun

- Structure and Cash-flows

In this structure, a hedge fund (HF) advises the prime broker (PB) to sell an option to purchase shares (S) in a particular entity at a specified price (US$ 100 in the illustrative diagram below (ID)), with delivery to take place on a specified date in the future (Day 10 in the ID) (step 1, in the diagram below). PB then sells this option to the Buyer and receives an initial payment of US$ 70 from the Buyer (steps 2 and 3). In the present example,

(i) the Buyer takes a ‘long’ position on S – i.e. the Buyer expects the market value of S on Day 10 to be greater than US$ 70; and (ii) HF takes a ‘short’ position on S –

i.e. HF expects the market value of S on Day 10 to be less than US$ 70.

Simultaneously with steps 2 and 3, PB enters into an arbun contract with HF, whereby PB pays HF US$ 68 (US$ 70 minus PB’s spread of US$ 2), with HF obliged to deliver S on Day 10 (step 4).

On Day 10, if the Buyer chooses to exercise the option to buy S and proceeds with the transaction, the Buyer pays PB the remainder of the purchase price (US$ 30) (the Remainder). The exercise of the option by the Buyer triggers the legally binding obligations between the parties. Therefore, following payment of the Remainder by the Buyer, HF will be under an obligation to purchase the stocks and deliver them to PB, who will pass them on to the Buyer. PB therefore pays HF US$ 30 (step 5), following which HF purchases S from the market on Day 10 (steps 6 and 7) and delivers it to PB. (step 8). PB then passes S on to the Buyer.

It should be noted that the higher the initial deposit payment the lower is the risk for HF, since the return is higher (in the event the Buyer chooses not to exercise its option). The deposit payment on Day 1 should therefore represent at least a third of the total purchase price; a “minority” as per the sayings of the Hadith, to contribute to the Shari’a-compliance of such a structure.

- Industry Usage

In June 2008, Barclays Capital and the Dubai Multi Commodities Centre Authority (DMCC) announced the first Shari’a-compliant hedge funds to be launched on the Al Safi Trust alternative investment platform. DMCC has

In this structure, a hedge fund (HF) advises the prime broker (PB) to sell an option to purchase shares (S) in a particular entity at a specified price (US$ 100 in the illustrative diagram below (ID)), with delivery to take place on a specified date in the future (Day 10 in the ID) (step 1, in the diagram below). PB then sells this option to the Buyer and receives an initial payment of US$ 70 from the Buyer (steps 2 and 3). In the present example,

(i) the Buyer takes a ‘long’ position on S – i.e. the Buyer expects the market value of S on Day 10 to be greater than US$ 70; and (ii) HF takes a ‘short’ position on S –

i.e. HF expects the market value of S on Day 10 to be less than US$ 70.

Simultaneously with steps 2 and 3, PB enters into an arbun contract with HF, whereby PB pays HF US$ 68 (US$ 70 minus PB’s spread of US$ 2), with HF obliged to deliver S on Day 10 (step 4).

On Day 10, if the Buyer chooses to exercise the option to buy S and proceeds with the transaction, the Buyer pays PB the remainder of the purchase price (US$ 30) (the Remainder). The exercise of the option by the Buyer triggers the legally binding obligations between the parties. Therefore, following payment of the Remainder by the Buyer, HF will be under an obligation to purchase the stocks and deliver them to PB, who will pass them on to the Buyer. PB therefore pays HF US$ 30 (step 5), following which HF purchases S from the market on Day 10 (steps 6 and 7) and delivers it to PB. (step 8). PB then passes S on to the Buyer.

It should be noted that the higher the initial deposit payment the lower is the risk for HF, since the return is higher (in the event the Buyer chooses not to exercise its option). The deposit payment on Day 1 should therefore represent at least a third of the total purchase price; a “minority” as per the sayings of the Hadith, to contribute to the Shari’a-compliance of such a structure.

- Industry Usage

In June 2008, Barclays Capital and the Dubai Multi Commodities Centre Authority (DMCC) announced the first Shari’a-compliant hedge funds to be launched on the Al Safi Trust alternative investment platform. DMCC has committed seed capital of US$ 50 million to each of four commodity hedge fund managers on the Al Safi platform, for a Shari’a compliant ‘fund of funds’ product to be offered under the Dubai Shari’a Asset Management (DSAM) brand. The Al-Safi fund utilises the arbun structure in order to replicate the economic effects of short-selling.

- Short-selling using Salam

- Structure and Cash-flows

In this structure, a hedge fund (HF) advises the prime broker (PB) to sell shares (S) in a particular entity at a specified price (US$ 100 in the illustrative diagram below (ID)) on Day 1 (step 1, in the diagram below). Once PB has sold S to the Buyer (with delivery to the Buyer to be on Day 10) and received US$ 100 (steps 2 and 3), PB enters into a Salam contract with HF whereby PB pays US$ 98 on Day 1 (US$ 100 minus PB’s spread of US$ 2) (step 4) and HF undertakes on deliver S on Day 10.

In the present example, HF takes a ‘short’ position on S – i.e. HF expects the market value of S on Day 10 (X) to be less than US$ 70.

On Day 10, HF buys S from the market (Seller) (steps 5 and 6) for X (US$ 80 in ID) and delivers S to PB (step 7).

- Industry usage

Newedge, a brokerage jointly owned by Calyon and Societe Generale, uses Salam contracts to enable hedge funds on its platform (launched in October 2005) to replicate the mechanics of conventional short-selling. Comment- ing on this structure, Teilhard de Chardin, global head of prime brokerage at Newedge in London says:

“Although different solutions seem more acceptable for different regions, many Saudi scholars prefer the Salam contract for equities, which is why we have taken this route.”

Legal and regulatory concerns

The tremendous growth of the Islamic finance industry in recent years has prompted several commentators to question the existence and effectiveness (or lack thereof) of central/regional regulatory bodies.118 The efforts of AAOIFI, IIFM and the Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB) to produce guidance notes and/or Shari’a standards (as the case may be) – while commendable, have not yet achieved the desired level of harmonisation. The resulting lack of uniformity is compounded by the absence of a codified body of laws governing Shari’a-compliant transactions/products.

Regulation is carried out mostly at the micro level, with banks appointing their own Shari’a Boards (comprised of Shari’a scholars) who examine the Shari’a compliance of new products (and often, also monitor the ongoing compliance of these products). Divergence of opinions among different Shari’a Boards adds to the lack of uniformity mentioned above.

Such divergences of opinion in the Islamic finance industry was highlighted in the aftermath of a declaration made by Sheikh Taqi Usmani (a respected Shari’a scholar) in 2007 that up to 85% of the sukuk-based products in the market at that date were not Shari’a– compliant and hence, unenforceable. The sukuk market was thrown into turmoil overnight and relative stability was restored only after a statement on the boundaries of permissibility in relation to sukuk was issued by the AAOIFI in February 2008.

In recent times, complicated Shari’a-compliant financial structures and derivative products have been criticised by certain commentators such as Sheikh Yusuf Talal de Lorenzo (please see Section 14.5.4 above) on the ground that in the process of financial decision-making (based on profit maximisation), Shari’a tenets are be- ing eroded. Such commentators argue that Shari’a– wrapping – i.e. the tendency of certain Shari’a Boards to approve financial products that are delivered by ostensibly halal means (even if the actual return delivered by those products is ultimately derived from non-compliant investments) is threatening to obscure and override Shari’a-based products – i.e. products which are rooted in the Shari’a, rather than being merely superficially compliant.

The above discussion is indicative of the lack of uniformity of opinions, which sometimes plagues specific products within the Islamic finance industry. Such divergences also take shape on a cross-jurisdictional basis. For example, the bai bithaman ajil contract is viewed as Shari’a compliant in South-East Asia, but its validity is not recognised in the GCC region.

The growth of the Islamic finance industry is contingent upon the development of investor confidence in this regard, which in turn rests upon a greater measure of uniformity of opinion and practice in relation to Shari’a-compliant products. A centralised regulatory regime could reconcile divergent opinions in the industry and produce industry-standard guidelines which would be very useful to all market players in the Islamic finance industry.

Conclusion: through the looking glass – the way forward

- The need for greater uniformity

As discussed above, the lack of a central regulatory body is perceived as an obstacle to the growth of investor confidence in Islamic finance. A good starting point to address this concern would be the MATP project (reference: Section 14.2.1(a)).

The MATP project was a natural forerunner to a joint initiative between ISDA and IIFM to produce a Master Agreement under which Shari’a-compliant hedging transactions can be documented. The ISDA/IIFM Tahawwut Master Agreement was launched on the 1st March in Bahrain after 4 years of hard work. Based in form and structure on the ISDA 2002 Master Agreement, it is very much hoped that it will bring liquidity, confidence and a convergence in pricing to the Islamic derivatives market.

Essentially the ISDA/IIFM Tahawwut Master Agreement is a multiproduct agreement on which all murabaha, musawama and wa’ad based Islamic products can be documented on. More analysis needs to be done to conclude whether salam and arbun based products can be documented on the ISDA/IIFM Tahawwut Master Agreement. It is pan-jurisdictional i.e. it can be used by all market participants regardless of their nexus to a particular madhab. At present the ISDA/IIFM Tahaw- wut Master Agreement sits outside the ISDA modular library e.g. it cannot be used with the Credit Defini- tions or Equity Definitions however, this is something that ISDA members will be discussing in the near future.

The most important concept within the ISDA/IIFM Ta- hawwut Master Agreement is the dichotomy between Transactions (concluded transaction) and Designated

Future Transactions (non-concluded transactions). The appreciation of this concept lies at the heart of the agreement and forms the cornerstone of the Islamic close-out mechanism.

Next steps include drafting template confirmations and working with ISDA to try and elicit enforceable netting opinions in the relevant jurisdictions.

The ISDA-IIFM Tahawwut Master Agreement (together with an Explanatory Memorandum) can be downloaded from both the ISDA website (www.isda.org) or at IIFM’s website (www.iifm.net).

Initiatives, such as the above, definitely illustrate progress towards achieving greater uniformity in Islamic derivatives.

- Innovation is the order of the day

As with any industry in its nascency, innovation could play a determining role in the growth of Islamic finance. With an increase in the number of Shari’a-compliant products in the market which can achieve a similar eco- nomic profile to comparable conventional products, the investor base is likely to increase. The following recent developments illustrate the recognition, by industry players, of the importance of innovation:

- Bursa Malaysia has announced its intention to launch:

- a palm-oil based commodity spot trading platform later this year (Commodity Murabaha House); and

- a Shari’a-compliant short-selling platform.120

- The Dubai Multi Commodities Centre (DMCC), in association with NASDAQ Dubai and the World Gold Council, launched Dubai Gold Securities (DGS) in March 2009. DGS offers investors exposure to the price of gold. The securities are backed by physical reserves of gold held by HSBC (as custodian).121

In Bahrain, the total value of Islamic assets increased from US$ 1.9 billion in 2000 to US$ 16.4 billion in early 2008.122 The introduction of a comprehensive prudential and reporting framework by the Central Bank of Bahrain has helped generate investor confidence and the market share of Islamic assets (as compared to total banking assets in Bahrain) increased from 1.8% in 2000 to 6.5% in early 2008.

- DIB recently bought back US$ 50.62 million of the five-year US$ 750 million sukuk issued by DIB Sukuk- Company Limited in 2007, at a 12% discount to the face value. This was the first-ever sukuk buy-back.

- Islamic finance and the credit crunch: new challenges and new opportunities

Based on the principle of risk-sharing that is inherent to Shari’a-compliant financing techniques, Islamic banks have broadly been better placed than their conventional counterparts to combat the effects of the credit crunch. While the Dow Jones Islamic Market World Emerging Markets Price Index rose 6.43% in the period from 01 October 2008 to 11 August 2009, the S&P 500 Composite Price Index and the FTSE 100 Price Index fell 14.36% and 5.82% respectively, over the same period.

Commenting on the difference in operational mechanics between Islamic and conventional banks, Abdel Bassat al-Shibi, managing director of Qatar International Islamic Bank, has stated that “Islamic banks don’t buy credit but manage concrete assets which shelter them from the difficulties that American and European banks are experiencing.”

While it may be too early to analyse the effects of the credit crunch on Islamic finance, it is worth noting that even in the current economic climate, there is appetite for Shari’a-compliant products, as evidenced by:

- the Government of Bahrain’s recent sukuk being eight times oversubscribed; and

- the Republic of Indonesia’s inaugural US$ 650 million

sukukbeing several times oversubscribed.

However, Islamic financial institutions are not completely insulated from the effects of the credit crunch. Several sukuk issuances and launches of innovative derivative products have been presently placed in a holding pattern, till the markets indicate definite signs of recovery.

- A growing market with significant potential

Today, it is estimated that there are Shari’a-compliant assets worth at least US$ 750 billion globally, with this figure expected to reach US$ 1.5 trillion by the end of 2010. A recent report suggests that Islamic banking has expanded by more than 10% annually over the past decade,128 with daily turnover in Shari’a-compliant transactions possibly running into billions of dollars.129 Islamic finance has the potential to be the new star on the investment horizon. Already, its appeal is spreading fast beyond the shores of conventional hubs such as the GCC region and Malaysia, as is apparent from the following developments:

- The Islamic Bank of Thailand (IBT) plans to raise be- tween US$ 70 million to US$ 200 million through the issue of sukuk in Malaysia and the Middle East by the end of 2009;130

- VTB Capital plans to develop Shari’a-compliant products and market these in Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS);

- The Law Governing the Operation of Islamic Banks by the Central Bank of Nigeria was enacted in March 2009. This creates a level playing field for Islamic financial institutions and conventional banks in Nigeria. Diamond Bank is one of the major players in the Islamic finance space in Nigeria. 65 % of Nigeria’s estimated 150 million population is Muslim;

- South Korean government officials have issued several public statements advocating a greater role for Islamic finance in the country’s financial system. Korea Development Bank and the Abu Dhabi Investment Corporation are presently holding talks with a view to identifying investment opportunities in South Korea; and

BTA Bank, Kazakhstan’s second-biggest bank by as- sets, is considering opening an Islamic banking unit, in collaboration with Dubai-based Emirates Islamic Bank. Kazakhstan has also promulgated a new law (The Islamic Finance Law 2009) which amends several aspects of the existing legal framework (including the Law on Banks and Banking Activity in the Republic of Kazakhstan, 1995), and is intended to broaden the range of finance options available to Kazakhstani companies.

While only time will tell to what extent the above initiatives are successful, it is certain that with sustained innovation and greater uniformity in application, Islamic finance will continue to appeal to a wide class of investors. The global markets are gradually reviving themselves and amidst the green shoots, Islamic finance appears to be a very promising bud.