Introduction

Ever since the collapse and subsequent nationalisation of many conventional financial institutions around the globe, the world credit market has experienced significant tightening, with financial institutions more risk-averse in their lending decisions. The days of cheap and easy credit that had fuelled private equity growth over the past years may have come to a temporary halt. However, this situation may prove to be an opportunity for other capital and debt providers to grow as an alternative investment platform – institutions such as Islamic banks and IPE investors, because of their fundamental principles in investing in the real economy, purely asset based financing or investment and strict adherence to the Shari’a. Through the sharing of risk, prohibition of interest and uncertainty in a transaction, the Islamic finance industry has generally been less affected by the recent downturn in the global financial markets. Although 2010 will be a challenging year for both the conventional and Islamic financial institutions, the latter will still see benefits based on its sound fundamental principles and liquidity.

Size, growth and regional trends of IpE

The PE industry is reported to be worth around US$ trillion, with the IPE industry comprising around US$ billion67. Market reports have typically combined PE funds with real estate funds and leasing funds. Most Shari’a-compliant PE funds originate in the MENA and account for 39% of the market. In terms of fund size, PE and real estate funds are the third largest in the Islamic fund universe- after Equity and Fixed income. In this respect, the MENA region has the largest concentration of high-valued funds. A 2007 CORECAP (an alternative investment firm with operations in Dubai and Qatar focusing on the Middle East and Asia) report predicted the Islamic PE market in the Gulf to grow to US$ 41 billion by 2011.

Gulf States have stressed that they wish to diversify their economies through technology transfer and entrepreneurship in a host of industries including real estate, healthcare, aviation, energy and telecommunication. PE players such as RHT Partners have been active in targeting IPO centric sectors and were involved in the AED 750 million (US$ 204 million) Dubai Madaares education deal. Other players such as Venture Capital Bank launched a US$ 100 million real estate fund, and established regional player Abraaj raised a US$ 3 billion Shari’a-compliant fund in 2006.

Offshore jurisdictions such as the Cayman and Jersey tend to be prominent bases for real estate and PE funds. Capital outflow from the petrodollar-rich Gulf to mature markets has been a continued theme, albeit more recently stifled due to regional difficulties exasperated by the local real estate asset price decline. Nonetheless, the large Sovereign Wealth Funds have significant funds and are actively targeting quality assets in both western and increasingly so in the emerging markets and BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) countries.

The Middle East is also seeing increased interest from overseas players attracted by the impressive growth rates in the region. The Carlyle Group has set up offices in the region, regarding it to be the fourth largest private equity center of the world.

This has led to the creation of several parallel funds. In 2008, Global Investment House, Millennium Capital and DIB developed a US$ 500 million buy-out fund, set up as a parallel Shari’a-compliant investment vehicle to the US$ 615 million Global Buyout Fund. The Islamic Buy-out Fund intends to pursue, together with the existing Global Buyout Fund or independently, Shari’a-compliant buyout opportunities in the Middle East and North Africa, South and South East Asia regions.68 For an IPE, the investing principles should not be any different from the conventional, and that means being well diversified in their portfolio across asset classes and geography. The substantial portion of Shari’a-based funds that originate from MENA by no means suggest that the deal flows can only originate from and be invested in Muslim countries. The Asian growth story is still compelling despite the recent crisis in the financial markets with China, India and the emerging economies looking for new capital to fund infrastructure needs and other growth opportunities. This provides an opportunity for IPEs to pursue investments in non-Islamic jurisdictions and for non-Islamic investors to partner IPEs in pursuing deals. Recently, a number of non-Islamic countries including the UK, Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore and Thailand, have embraced Islamic finance and are encouraging its growth in their respective countries by attracting funds from the GCC.

The growth of Islamic assets

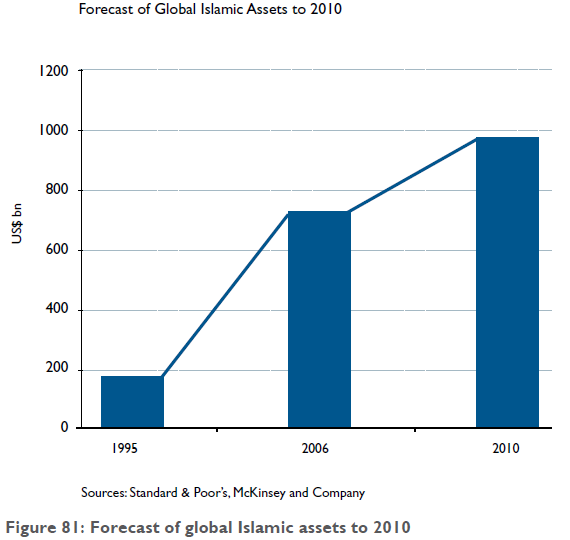

Islamic assets have experienced significant growth over the past years – from a humble size of less than US$ 200 billion in 1995, to an estimated size of up to c.US$ 1 trillion by 2010 and c.US$ 1.6 trillion by 2012, with

revenues of US$ 120 billion. It is believed that Islamic products will continue to reach out and appeal to both the Islamic and non-Islamic communities. Given the increase in demand for Islamic products by the Islamic and non-Islamic communities, it is not surprising that the global Islamic assets are forecast to grow rapidly at a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of between 10% and 15% – a much faster rate than conventional financial institutions.

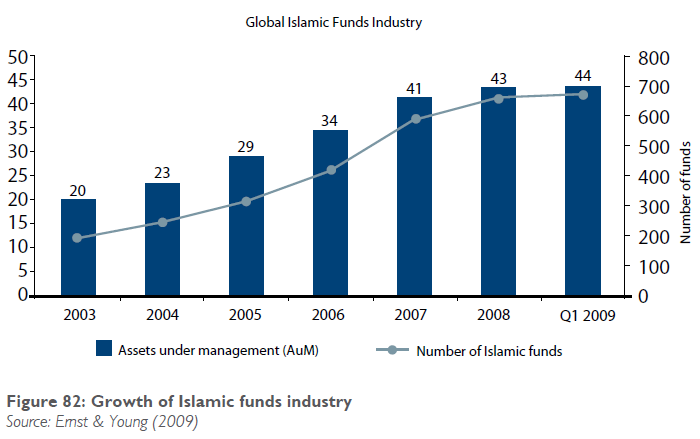

A recent Ernst & Young report shows that there has been a positive trend in the number of Islamic funds over the past 6 years, although this growth has stalled somewhat from its historic highs in the past year.

Financial analysts in both South East Asia and the MENA region expect that the economic downturn will provide the general PE industry significant scope for expansion in 2010 (as valuations are deemed increasingly attractive), which will naturally precipitate the growth of Islamic PE.

Demystifying pE

The United States has undoubtedly been a forerunner of the modern-day private equity market. They have facilitated the advance of the industry since the end of World War II, through entrepreneurial vision and changes in legislation.

In the 1960s, there were two key developments which led to the maturity of the market. The first was the PE fund with Limited Partner/General Partner structure, which gained popularity and was later adopted throughout the industry. The second development was the Leveraged Buy-Out (LBO) model innovated by the investment bank Bear Sterns, to facilitate the buy-out of family-owned businesses.

Legislative changes, new stock market indices for small-cap companies, and liberalization of the financial regulatory system in prominent capitalist economies from the 70s onwards, enabled the PE market to become global.

Deconstructing PE investments

The term “private equity” represents a diverse set of investors who typically take a majority equity stake in a private limited company. There are three main types of PE activity.

Venture capital: The funding of a new business, typically early stage that is unable to source debt funding from a bank (possibly IP centric or lacks a certainty of cash flow);

Development capital: Investment in an existing business to help it expand;

Buy-out: Funding the purchase of an established business where there is perceived scope for improvement;

PE is a medium to long-term finance (usually three to seven years) provided in return for an equity stake in potentially high-growth companies that are unlisted.

During the holding period, the strategy of the PE fund would be to improve the profitability of the company with a view to increase value upon exit.

There are subtle differences in the use of terminology across the Western world. In Europe, PE is synonymous with venture capital, and is used to cover funding at all stages of a business life cycle. In the US, venture capital refers primarily to investments in early-stage companies.

Generally, PE funds are structured as partnerships with two key components: the general partnership (GP) – where the management team is responsible for making the investment decisions; and the limited partnership (LP), providers of the capital.

The LP will commit the funding that allows the GP to make a drawdown for investments that meet the targeted profile. There is typically a hurdle rate set by the LP which represents a minimum investment return target for the GP. Returns in excess of this are split with the GP on a pre-determined rate (often referred to as “carry”).

A buy-out model typically involves creating a three-tier structure consisting of a holding company, its subsidiary, and a subsidiary of the first subsidiary. This structure allows a separation of the loan capital (provided by the bank), equity capital (provided by investors) and the services of the management69. Virtually all buyouts use a certain amount of leverage, using the assets of the company as security. This is why they have become known as LBO. Typical PE buy-out transactions (up to 2008) constituted two third debt and one-third equity.

Current status

Up until the early part of 2008, there has been significant growth and attention paid to the PE sector. How- ever, the sector has fallen victim to its own success, with a number of new players in the PE arena – for example, hedge funds, who have been heavily criticised for their aggressive investment strategies. This has culminated in an environment where too much capital is chasing too few quality deals. In addition, as the influence of PE firms over local economies increases, (e.g. PE firms reportedly employ a third of the UK workforce), government bodies and ministers have begun raising concerns over high levels of leverage. Negative sentiments associated with the LBO firms of the past, appear to be resurfacing, with strap lines such as ‘PE – locust or lifeline?’ being raised. As a direct result, in the UK, the Walker report was commissioned. This report detailed a set of guidelines requiring PE funds to increase their disclosure both at a fund and portfolio level.

Since the banking crisis of 2007, and the seizure of the interbank market along with various well documented banking collapses, the market has seen significant deleveraging which has bought PE activity to a sudden and abrupt standstill. Over the last 18 months, recessionary periods have caused a significant downward pressure on the revenue lines of highly leveraged PE companies, bringing many of them close to breaching banking covenants. This has resulted in the unwinding of select funds from large PE managers such as Candover, and the fire-sale (or liquidation) of certain portfolio assets.

IpE

IPE investors are no different from their conventional cousins in terms of capital that is targeted towards medium to long-term investments; having a clear exit strategy at the onset and ensuring returns commensurate with the risk taken. Apart from capital contribution, PE investors bring discipline and management expertise to help maximise shareholder value. The distinct difference between an Islamic and a conventional PE lies in the way investments are approached. The IPE approach to investments is largely driven by Islamic injunctions related with economics and finance. Islamic economics and finance are rooted in some fundamental principles of Shari’a, the code of law that regulates the conduct of Muslims in their individual and collective lives, and enshrined in the Holy Quran.

Another difference between IPE and conventional PE investors is in the governance structure of the IPE. Whilst both the Islamic and conventional PE have their own Investment Committees, an added layer in the form of Shari’a advisory board is mandatory in IPEs. The primary role of the Shari’a advisory board is to supervise the Shari’a compliance of all the transactions and conduct of the IPE.

The most important principles of Shari’a are the prohibition of riba (interest), gharar (uncertainty), maysir (equivalent of gambling) and forbidden transactions (such as liquor, pork trading, weapons and other unethical investments).

Musharaka and mudaraba investments by IpE

Out of the three most common alternative investment classes under the Shari’a, namely real estate, PE and hedge funds; the PE asset class has been the most desired form of financial business based on either musharaka or mudaraba transactions.

Musharaka transactions are commonly used for infrastructure projects where the investee party or project partners provide the asset and the IPE provides the fund to develop or utilise the asset. In musharaka contracts, the ownership of the project usually transfers to the investee company or to the project partners at the end of the venture (or progressively through a diminishing musharaka structure). Alternatively, the IPE could exit through the traditional routes, either through an initial public offering or a trade sale.

Mudaraba transactions are similar to musharaka except that the investee party or project partners do not contribute any assets to the partnership. The investee or project partners contribute skills in managing the business, whilst the IPE contributes the capital. This is common in Management Buy Outs (MBOs). In both the investment modes, the basic tenet of profit and loss sharing is prevalent – the cornerstone of Islamic investments. In musharaka and mudaraba investments, partners share the profit of the joint venture at a pre-agreed rate, but losses in proportion to capital contributed in musharaka investments and entirely by the investor in mudaraba investments.

The common misconception amongst non-Muslim business communities is that Islamic finance is not secular and can only be transacted with Muslims. This misconception is probably one of the reasons why IPE has not transformed itself as a key contributor to long-term capital in Asia to assist private companies to grow and succeed–unlike their conventional cousins. In fact, musharaka and mudaraba IPE investments can be transacted with non-Muslims and also with interest-based banks to carry out activities acceptable in the Shari’a. How- ever, arrangements must be made to obtain all necessary guarantees that the principles of Shari’a will not be compromised during the tenure of the partnership.

IpE as an investor

Most business activities are generally permissible except for certain sectors that are screened by the Shari’a to be prohibitive. These prohibitive sectors include gambling, pork trading, weapons, alcohol and unethical businesses. Apart from sector prohibitions, certain financial prohibitions are also applied when deciding if a business is compliant with Shari’a. These include if the business has an interest-based debt, unacceptable liquidity ratio and, significant level of investment and trading in debt instruments. The financial prohibition under Shari’a does not preclude an investment by an IPE into a target if at the onset of the transaction; a restructuring of the non-Shari’a aspects of the business can be agreed upon or carved out, with the agreement of the IPE’s Shari’a advisory board. Depending on the type of financial assets or liabilities that are prohibited, most Shari’a scholars take a view that within three years of taking control of the target, the financial prohibition must no longer prevail.

Accordingly, IPE would usually require majority control in a venture in order to drive the business from a Shari’a compliance perspective, and to ensure that any financial prohibitions are restructured in accordance with the agreement of other co-investors and/or management at the onset of the transaction. Some of the major changes to a business that will be brought in by an IPE to a target post-deal include:

- Conformity of legal documentation to Shari’a;

- Phasing out of non-Shari’a-compliant financial transactions

- Certain minor non-Shari’a-compliant activities may be tolerated

- Freezing or phasing out of interest-bearing debt arrangement

- Alignment of all equity relationships, including those with existing shareholders, with Shari’a (no liquidation preference)

Whilst IPEs would still consider majority investment into businesses with non-Shari’a financial elements, IPEs generally prefer venture capital or green field investments as it is easier to introduce Shari’a requirements right at the beginning of the business life cycle, than to make changes to an existing business that may already be well established. To untie or terminate prematurely inter- est bearing debt structures and substitute with Islamic debt or gradual disposal of debt investments may cause significant loss to an existing business and could impair long-term shareholder value.

Market players present varying approaches to Shari’a compliance, which can be summarized as:

Puritan method – all investment used in the acquisition stage and in the underlying portfolio company are Shari’a-compliant at the outset. This could be through acquiring via a 100% equity cheque or commodity mu- rahaba structures/tawarruq (albeit controversial) used as alternative debt structuring. The underlying portfolio company is also expected to have Islamic financing only.

Conversion period: where a period of time is given for the PE fund to actively convert all the debt financing into Shari’a-compliant alternatives. Again this could be through the use of issuing corporate sukuk, tawarruq, changing to operating leases using ijara, or simply broadly reducing debt.

‘Middle man’ approach – effectively the Shari’a requirement is restricted to a holding company which consequently allows the use of conventional debt as typically deployed within a conventional PE structure.

Major challenges facing IpE and Islamic finance

Whilst Islamic trade in conformity to Shari’a has been practiced since the days of Prophet Muhammad (pbuh), IPE as an alternate class of investment is still at its infancy stage. The concept of Islamic investment banking is relatively new and caters for the increased needs of over

1.6 billion Muslims who require products and investments that comply with their divine and spiritual needs. Mirroring conventional products with a tweak in the underlying structures have come under the heavy scrutiny of Shari’a scholars. This is due to the lack of learned professionals in Shari’a structuring, compounded by the lack of readily available information, and differing opinions of Shari’a scholars in this rather specialised area of finance. Clearly, investments into Shari’a resources need to be increased and a common opinion amongst Shari’a scholars is needed in order to have a wider acceptance of Islamic financial products.

There are Shari’a concerns on both the limited and general partnership level. The primary challenge is the high use of leverage in a typical PE transaction. To address this, either a 100% equity cheque needs to be written (which in turn compresses returns), or an Islamic debt needs to be sourced.

The same challenge prevails where the underlying company has to refinance its existing conventional debt into an Islamic alternative. This problem is further exasperated in areas where the Islamic finance industry is still underdeveloped (e.g., working capital solutions, hedging instruments or mezzanine financing structures).

Another key challenge for the growth of IPE and Islamic finance in Asia (and to a large extent globally) is the tax regime and the question of substance over form on whether tax structure are financing in nature or a business venture? Tax rules have developed in tandem with conventional approaches to financing and most jurisdictions face difficulties in applying tax rules to Islamic financial products. Tax has therefore been a hindrance to the use of Islamic finance and the common tax issues include duplication of transaction taxes (eg. stamp duty), differences in taxation treatment of interest (conventional) and profit distribution in Islamic finance, application of withholding tax, GST/VAT implications and entitlement over capital allowances. In order to get a slice of the multibillion-dollar global Islamic finance business, certain countries including Singapore, Malaysia and the UK have taken considerable measures in introducing changes to their banking and tax laws to cater for a level playing field for both Islamic and conventional products. Some of the tax issues can be resolved by applying normal tax principles and rules, considering tax neutrality and engaging tax authorities in advance to pre-agreed tax implications.

Future prospect for IpE

Notwithstanding the recent catastrophic events impacting the conventional markets, in broad terms Islamic finance continues to enjoy a period of strong growth. Asset classes like PE are expected to benefit as they provide an attractive outlet for equity-based investment which is deemed to have a natural fit for the guiding principles inherent in Islamic finance. This is resulting in a greater number of Islamic banks becoming involved in PE deals by setting up their own PE funds.

Islamic banks should be aware however that the PE model requires a broader mindset which extends be- yond financial engineering to include operational improvements. IPE today is primarily dominated by individuals with retail/commercial banking experience with few having real PE focused transaction experience, which is materially different to the commercial banker mindset. There are very few true PE players (i.e. non real-estate funds) in the Islamic arena which can demonstrate best practice experience from the West and strong local market knowledge. Many funds tend to be real estate orientated and the business of evaluating businesses is significantly different. Accordingly, the emergence of a true PE focused market leader is, as yet, difficult to identify.

Certain established regional conventional players in the Gulf have raised IPE, however certain market critics have taken a cynical view of players tacking on the ‘Islamic’ to benefit from the industry as opposed to benefiting the industry. To engage effectively in PE deals, Islamic players need to ensure that they have the appropriate resources – experienced individuals with proven track records or alternatively, they should consider partnering up with existing boutiques or deploy a ‘fund of funds’ approach. The need to present a diversified investment strategy will inherently continue to fuel IPE growth. This coupled with the current reduction in asset valuations (presenting attractive acquisition targets) and the Islamic finance industry’s search for credibility (within a true equity-based solution), collectively presents a positive outlook for IPE.