Introduction

Given the unprecedented upheaval and destruction wrought by two world wars, much of the 20th Century infrastructure development in industrialized countries was funded by governments, using the budgetary re- sources at their disposal. This trend began to change in the early 1980s, when cash-strapped Western Governments realized that private sources of capital could be mobilized to reduce the burden on public sector budgets, whilst still meeting the infrastructure demands of growing populations and increasingly diversified economies. This trend has been adopted in much of the developing world during the last twenty years, and has resulted in the emergence of the project finance sector, much as we know it today.

Size, growth and regional trends of Islamic project finance

Current global Islamic finance assets stand at approximately US$ 1 trillion and on current projections could be worth around US$ 4 trillion by 2015. With an annual average growth rate of between 15% and 20% Islamic finance is amongst the fastest-growing sector of the finance industry. The belief is held by many, including the Vatican that the current financial crisis would not have happened if the world economy was based on underlying Islamic finance principles. The prospect for Islamic finance and consequently Islamic project finance are excellent.

It is estimated that the project financing requirement in the GCC, countries alone over the next 5 years will be in the region of US$ 1 trillion. On the basis of currents trends, around 30% of that amount is likely to be met through Islamic project financing. With Saudi Arabia ac- counting for approximately US$ 400 billion of the de- mand for project finance, it is possible that the percentage of Islamic project financing may reach up to 50% in the coming years. Figure 72 below briefly portrays the trend in Islamic project finance. The resource rich economies of the GCC were amongst the first in the developing world to adopt project finance as a means of developing critical infrastructure such as power and desalination plants, and the industrial infrastructure required to enhance the downstream processing capabilities of their hydrocarbons government and quasi-government agencies, much of the growth in infrastructure that we see in the region today is the direct result of the application of project finance techniques by governments, sponsors and financial institutions.

The first major project financing to involve Islamic finance was the US$ 1.8 billion Hub River Power Project in Pakistan. The Islamic and conventional co-financing involved a US$ 92 million istisna’ facility (used for the manufacture of turbines for the project) which was provided by Al-Rajhi Bank. Project Finance International magazine named the project its 1995 “Deal of the Year”. Pakistan’s Federal Shari’a Court ruled that the US$ 92 million funding was not a loan but a purchase and resale of the turbines.

The year 1996 saw the financial closing of the US$ 2 billion Equate petrochemical project in Kuwait, which included a US$ 200 million Islamic project financing tranche. Unlike the istisna’ structure used in the Hub River Project, the Equate Project used a floating rate (sale and leaseback) ijara financing structure (in respect of existing equipment which was acquired and incorporated into the petrochemical plant). The decision to use an Islamic finance tranche for the Equate Project gave rise to a number of issues relating to the structuring of the inter-creditor relationship between the conventional and Islamic banks, and the ownership of the leased as sets and the risk associated with ownership of the assets forming part of a petrochemical plant (with potentially serious environmental and third party risks for the banks as owners of the specified project assets).

From 1996 to 2006, the value of Islamic tranches in project finance continued to increase in size in the GCC, perhaps not surprisingly in the wake of the September 11 2001 attacks, and the subsequent freezing of the international credit markets. Abu Dhabi Islamic Bank underwrote a US$ 250 million Islamic tranche for the Shu- waihat power and water project in Abu Dhabi. One of the largest deals was the US$ 847 million Islamic finance tranche raised by SABIC’s subsidiary Yanbu National Petrochemical Company for a greenfield petrochemical facility. SABIC has itself obtained one of the largest ever Islamic financing, when it raised a US$ 1 billion mura-haba facility arranged by Deutsche Bank in 2006.

A sign of the diversification away from the power and petrochemical industries was the project financing of the Thuraya Satellite Project, in 1999, which included an Islamic construction finance and leasing tranche worth US$ 100 million as part of the overall US$ 600 million financing for the project. This project showed that Islamic project financing could be applied to the development of technologically advanced projects and facilities.

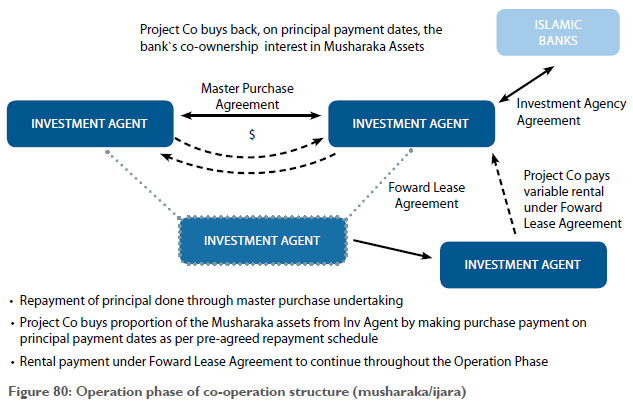

The first greenfield petrochemical project financed on a purely Islamic finance basis was the 2006 financing for the Al-Waha Petrochemical Company (Al Waha). This involved a combination of a musharaka, procurement and forward lease arrangement. The financing involved a co-purchase agreement between the investment agent (on behalf of the banks) and Al-Waha, under which Al- Waha assumed the responsibility for the construction of the plant. The banks agreed to fund a portion of the costs incurred by Al-Waha under the turnkey construction arrangement, and took a proportionate share in the ownership of the project assets reflecting their investment in the project. The operating phase involves the banks leasing their ownership interest in assets to Al- Waha for a period of 11 years. The structure allows Al- Waha to purchase portions of the project assets owned by the banks at semi annual intervals during the operating phase, pursuant to a purchase undertaking.

In a further important development in the Islamic project finance industry, the first concession based transport infrastructure project to be financed on a purely Islamic finance basis achieved financial closing in 2007. The project was the Doraleh Container Terminal Project, which involved the development, design, construction, management, operation and maintenance of a new container terminal at Doraleh, Republic of Djibouti. This project demonstrated just how far Islamic project finance had developed within a relatively short period of time. It has one of the longest tenors in the history of Islamic finance and is the first Islamic project financing to benefit the World Bank Group’s MIGA political risk guarantee.

As a result of the specialised nature of project finance, the Islamic project finance market has, until recently, been dominated by the Islamic affiliates of conventional banks such as HSBC, Citigroup and Standard Chartered. Recent transactions such as the Doraleh Container Terminal Project and the US$ 2.5 billion Rabigh IPP Project, which closed in July 2009, have involved Islamic and participating in complex Islamic project financing. The US$ 1.5 billion Islamic financing for Rabigh IPP Project was provided by Al Rajhi Banks, Alinma Bank, National Commercial Bank, Samba and Saudi British Bank.

The concentration of experienced project finance bankers, international lawyers, consultants and advisors over the last 5 years has made Dubai the main centre for structuring complex Islamic project financing, although Bahrain remains an important centre for the Islamic finance industry generally. The number of major projects requiring Islamic project finance in Saudi Arabia means that there is increased demand for experienced bankers and advisors in Riyadh and Jeddah.

Islamic project finance

The Islamic finance sector has three unique characteristics which allow it to play an increasingly important role in the project finance arena. Firstly, Islamic banks are perceived as holding the key to pools of liquidity that would otherwise be unavailable for projects financed purely on a conventional basis.

Secondly, Islamic financing products are capable of be- ing structured in to deals with a multiplicity of financing sources. The increasing scale of infrastructure projects in the GCC region means that Islamic financing can pro- vide ‘additional value’ by plugging gaps in liquidity. It is now virtually inconceivable that a mega-project in the region would be structured without a Shari’a-compliant component.

Thirdly, and of increasing importance, is the fact that projects which have been financed on a Shari’a-compliant basis benefit from increased credibility. On the one hand, governments are keen to foster the Islamic finance sector – not only through the issuance of sukuk, but by insisting on projects to be partly funded through Islamic finance products. On the other hand, sponsors are looking to the initial public offering (IPO) markets as a possible exit route, and have come to recognize that the public’s appetite (particularly in Saudi Arabia) for such companies is driven, at least in part, by compliance with Shari’a. Whilst the IPO market has all but disappeared in the region during the course of 2009, it will rebound in due course and offerings will need to continue to resonate with the ethical imperatives of investors.

Islamic financing instruments

Musharaka facility

- Co-ownership arrangement

- Proportion of ownership, timing and amount of contribution by each party is decided upfront

- Borrower is engaged as an independent contractor for procurement of assets

- Ownership of participant’s assets and associated risks remain with the borrower (as contractor) till the project completion

• Contractor receives funds from both lenders (debt) and borrower (equity) for procurement of asset

• Borrower buys a proportion of participant’s assets from lender by making purchase payment as per preagreed repayment schedule defined in purchase undertaking

• Borrower becomes the owner of the asset once it purchases the entire interest of lender Sukuk facility Some scholars have raised the following concerns with this type of financing:

• Most of the sukuks guarantee the return of principal by the obligor

• In case actual profit falls below the prescribed percentage, enterprise manager lends the amount of shortfall to the sukuk holders Murahaba facility

• Commodity murahaba: used to raise cash for working capital purpose

• Lender and borrower enter into a commodity trade

• Lender sells commodity to borrower on deferred payment basis

• Borrower receives cash by selling commodity to a

- commodity broke Asset murahaba: used for acquiring assets required for business

• Borrower requests lender to purchase an asset

• Borrower organises the acquisition of asset

• Lender makes direct payment to the supplier of the asset

• Lender on-sells the asset to borrower on deferred payment basis Ijara facility

• Lender acquires an asset at the request of the borrower

• Leases it to borrower for an agreed period and agreed rent

• On occurrence of EOD or mandatory prepayment event, borrower shall buy the asset in consideration for outstanding debt (or Termination Sum)

• Borrower has the option to purchase the asset upon payment of purchase price as defined in Sale Undertaking

given by Investment Agent Istisna’

• Lenders disburse funds under an istisna’ agreement to meet project cost through Investment Agent

• Project company acts as contractor for the Project. After completion, asset rights are transferred to Investment

- Agent

Because of the way in which Islamic banks fund themselves – through the short-term deposits of customers – there remains a structural inability for Islamic banks to fund the lengthy tenors required by certain projects.

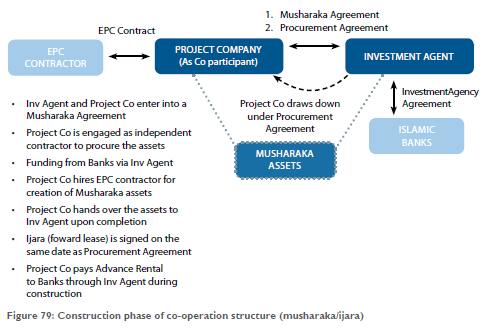

Figures 73 and 74 below describe the fundamental differences between Islamic and conventional financing. One interesting result of the current economic crisis is the general reduction of tenors for project finance deals, and the use of innovative structures such as mini- perms, which provide construction-phase financing and then require a refinancing for the longer revenue generating phase of the project. The adaptation of mini-perm solutions may well prove to be the optimal way for project financings to be structured involving Islamic finance products.

- project finance solution availability

The Shari’a-compliant structure used in Islamic project financing depends on whether the project is new (greenfield project) or whether it is an existing project that has already been constructed. For new projects, the preferred structure currently, is a combination of an istisna’ and a forward lease arrangement. For existing projects, a form of sale and lease back structure is usually preferred.

The main details of the preferred Shari’a-compliant

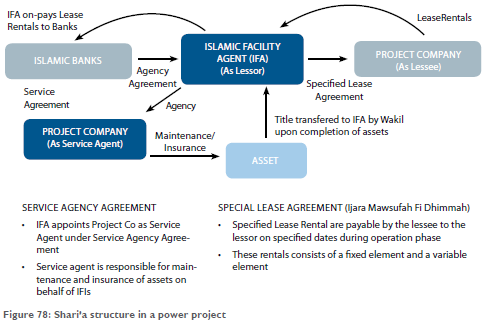

- Investment Agent leases the assets to Project Co for use until the final maturity date under FLA

- Inv Agent (as lessor) enters into Service Agency Agreement with Project Co (as service agent) to carry out certain owner’s obligations and pays to service agent a service fee Project Co makes rental payments to Inv Agent comprising fixed element, variable element and suppemental rend (being equel to service fee)

- Project Co grants a purchase undertaking in favour of Inv Agent: On occurrence of EOD, Project Co has to buy legal title on payment of outstanding debt (Termination Sum)

- Inv Agent grants a sale undertaking to Project Co pursuant to which it will sell its interest back to Project Co for nominal consideration on final maturity date provided there is no outstanding

- Inv Agent (as lessor) enters into Service Agency Agreement with Project Co (as service agent) to carry out certain owner’s obligations and pays to service agent a service fee Project Co makes rental payments to Inv Agent comprising fixed element, variable element and suppemental rend (being equel to service fee)

Figure 75: Example of Istisna’ structure

structures use for new (greenfield) projects are set out below.

- Istisna’

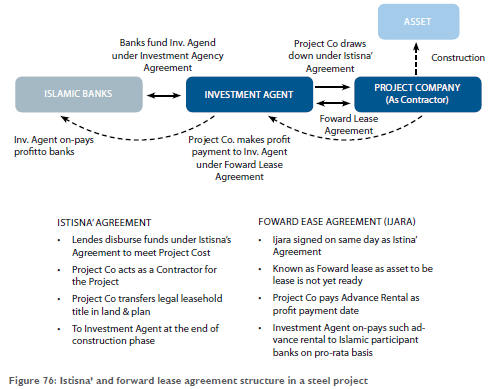

A traditional istisna’ involves one party undertaking to manufacture a specific asset with agreed specifications for a fixed price. The price can be paid upfront or on a deferred instalment basis in the future. Structuring of such product is exhibited in Figures 75 and 76 below

In order to avoid the need for the banks to enter into a contract with the engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) contractor, Islamic project financings usually involve the investment agent (on behalf of the banks) entering into an istisna’ contract with the project company, under which the project company undertakes to construct and deliver the project assets. In order to ensure bankability of the project, the project company usually sub-contracts the works to an experienced EPC contractor appointed by the project company itself. Even though it sub-contracts the works to a third party EPC contractor, the project company remains strictly liable to deliver the project assets to the investment agent on time and to the agreed specification. In order to ensure certainty, the istisna’ contract will set out in detail, specifications of the project assets (reflecting the details contained in the EPC contract).

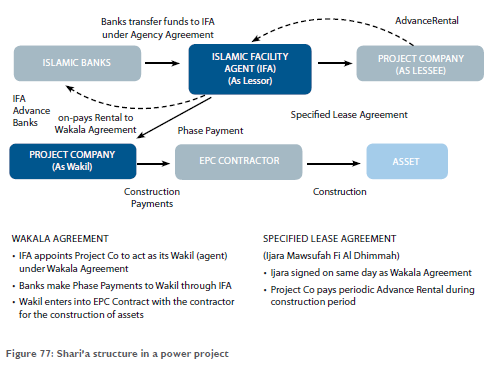

As an alternative to the banks entering into an istisna’ contract with the project company, they can enter into a procurement or wakala arrangement with the project company. An example of such structure is depicted in Figures 77 and 78 below. Under this arrangement the banks appoint the project company to procure the construction and delivery of the project assets. As in the case of an istisna’ arrangement, the project company will sub-contract the works to an EPC contractor, but remain strictly liable to deliver the project assets to the investment agent (on behalf of the banks) on time and to specification. The wakala or procurement contract does not need to contain the detailed specifications of the project assets, but will usually cross refer to the specifications set out in the EPC contract.

- Ijara

As mentioned above, ijara (as part of a sale and lease-back arrangement) is regularly used in Islamic project financing of existing projects.

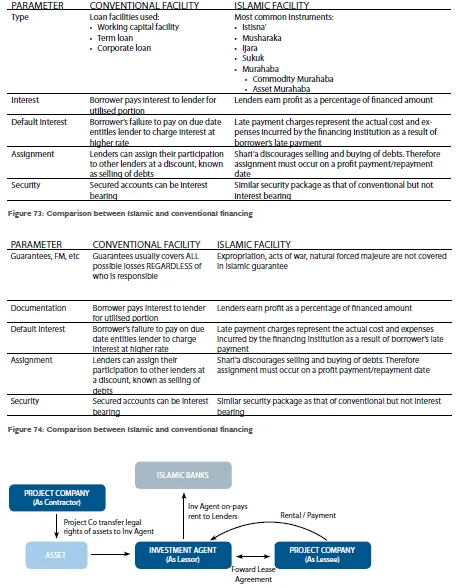

Using the traditional ijara (involving leasing of assets which are already in existence) would not provide the banks with a return during the construction phase of a greenfield project. As a result the istisna’ or procurement arrangement is usually combined with an ijara mawsufah fi al dhimmah (or “forward lease”) arrangement between the investment agent (on behalf of the banks) as lessor and the project company as lessee for the lease of the project assets, which will come into existence on the project completion date. Figures 79 and 80 depict the construction and operation phases, respectively, of such a product.

Although the ’actual’ lease period does not start until the project assets are delivered to the investment agent under the istisna’ or procurement contract, the project company pays ‘advance’ rental to ensure that the banks receive a return during the construction period. Since the ‘advance’ rental represents payment on account of the rental for a future ‘actual’ lease period, it is necessary for the ijara agreement to clearly state that the banks will reimburse all of the ‘advance’ rental received by them during the construction period, if the project assets are not delivered and therefore cannot be leased by the project company. It is important to note that the concept of a “forward lease” is not universally accepted by Shari’a scholars.

Multi-sourced projects

In multi-sourced projects where the Islamic tranche is only one part of the overall project financing package, all of the conventional and Islamic banks will enter into an inter-creditor agreement to regulate their relationship, and to ensure that they all share in any payments (whether voluntary or mandatory) on a pro rata basis, and that their facilities rank on a pari passu basis.

One important development in recent multi-sourced projects is the requirement from some Shari’a scholars that the proceeds of enforcement of security granted to the Islamic banks, or the sale proceeds of the Islamic leased assets can only be used to pay the principal, but not the interest component of the amounts due to the conventional banks. This has led to changes in the traditional enforcement payments waterfall to ensure compliance with Shari’a principles. The vibrancy of the Shuwaihat model has again been demonstrated on the recent financing for the Al Dur IWPP in Bahrain. This project, sponsored by Gulf Investment Corporation and GDF Suez, not only combined Islamic and conventional commercial debt, but also included a US$ 230 million facility from US Exim and insurance cover from KECI. As mentioned previously, this was also the first deal in the GCC region to use a mini perm structure, which gave the financing a tenor of eight years. The Shari’a-compliant tranche of US$ 300 million for Al Dur, provided by Al Rajhi, Banque Saudi Fransi.

Important structural considerations

- Ownership of project assets by a special-purpose company

In order to remove the ownership risk from the banks and to deal with restrictions on foreign ownership of project assets (where there is participation in an Islamic project financing by international banks who are not al- lowed, under local law, to hold an ownership interest in the project assets), the ownership interest of the project assets in an istisna’ – Forward Lease arrangement, may be held by a special purpose company (SPC) owned by local banks (or their affiliates). Having the SPC hold the title to the project assets removes the direct link between the banks and the project assets, thus mitigating the effect of any asset ownership related risk which the banks may otherwise face. The effectiveness of this structure will depend on the local laws of the country in which the project is located.

- Effect of total destruction of the project assets

A total loss of the leased project assets due, for example, to a natural catastrophe or an accident, gives rise to particular considerations in the context of an Islamically financed project. The commonly accepted view is that if the leased assets suffer a total loss and are therefore no longer capable of economic use by the lessee (project company), then the obligation to pay rent ceases upon the occurrence of the total loss event. As a result, any purchase undertaking in respect of the assets will also become ineffective. In order to deal with this situation, Shari’a scholars have agreed to allow the banks to appoint the project company as their service provider and for it to put in place and maintain insurances for the full replacement value of the project assets. In case of a total loss, the project company (as service provider) will be obliged to provide the banks with the proceeds of the insurance. If the proceeds are less than the full replacement value of the assets, the project company (as service provider) will have failed to satisfy its strict liability, and will be liable to indemnify the banks for any shortfall.

- Voluntary and mandatory prepayment

Unlike conventional financing, the project company can- not simply make a partial or full prepayment of the Is- lamic financing by issuing a notice of prepayment. The project company will instead need to exercise its rights under a call option (usually granted to it under the terms of a sale undertaking) to purchase from the banks (as lessors) some or all of the project’s assets, or an interest therein. In order to avoid the arrangement being considered as a sale and purchase of assets in the future, the arrangement is usually structured as a unilateral promise to sell given by the banks to the project company.

In the event that the project company is in material breach of its obligations under the financing arrangements, or the banks are required by law to cease their relationship with the project company, then (as in a conventional financing) the banks will have the right to require the project company to prepay the financing. The mechanism by which the banks will exercise their rights in such circumstances will be by exercising a put option (usually granted to them by the project company under the terms of a purchase undertaking), requiring the project company to purchase the project assets from the banks (as lessors). The exercise price will usually be the full amount outstanding under the Islamic project finance facility, and the banks will have the right to enforce against and liquidate any security given to them by the project.

Areas of Development

One of the principal growth areas of Islamic finance in recent years has been the issuance of sukuk. Given the asset based nature of project finance, it is rather sur- prising that, to date, sukuk have not been used as a means of raising capital for projects. There is anecdotal evidence to suggest that sponsors will increasingly seek to incorporate the issuance of sukuk in their financing plans. Moreover, the introduction by Tadawul66 of a sukuk trading platform is likely to lead to increased liquid- ity in that sector during the coming years.

- Investment Agent leases the assets to Project Co for use until the final maturity date under FLA

- Inv Agent (as lessor) enters into Service Agency Agreement with Project Co (as service agent) to carry out certain owner’s obligations and pays to service agent a service fee Project Co makes rental payments to Inv Agent comprising fixed element, variable element and suppemental rend (being equel to service fee)

- Project Co grants a purchase undertaking in favour of Inv Agent: On occurrence of EOD, Project Co has to buy legal title on payment of outstanding debt (Termination Sum)

- Inv Agent grants a sale undertaking to Project Co pursuant to which it will sell its interest back to Project Co for nominal consideration on final maturity date provided there is no outstanding

- Inv Agent (as lessor) enters into Service Agency Agreement with Project Co (as service agent) to carry out certain owner’s obligations and pays to service agent a service fee Project Co makes rental payments to Inv Agent comprising fixed element, variable element and suppemental rend (being equel to service fee)

- Istisna’

A traditional istisna’ involves one party undertaking to manufacture a specific asset with agreed specifications for a fixed price. The price can be paid upfront or on a deferred instalment basis in the future. Structuring of such product is exhibited in Figures 75 and 76 below

In order to avoid the need for the banks to enter into a contract with the engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) contractor, Islamic project financings usually involve the investment agent (on behalf of the banks) entering into an istisna’ contract with the project company, under which the project company undertakes to construct and deliver the project assets. In order to ensure bankability of the project, the project company usually sub-contracts the works to an experienced EPC contractor appointed by the project company itself. Even though it sub-contracts the works to a third party EPC contractor, the project company remains strictly liable to deliver the project assets to the investment agent on time and to the agreed specification. In order to ensure certainty, the istisna’ contract will set out in detail, specifications of the project assets (reflecting the details contained in the EPC contract).

As an alternative to the banks entering into an istisna’ contract with the project company, they can enter into a procurement or wakala arrangement with the project company. An example of such structure is depicted in Figures 77 and 78 below. Under this arrangement the banks appoint the project company to procure the construction and delivery of the project assets. As in the case of an istisna’ arrangement, the project company will sub-contract the works to an EPC contractor, but remain strictly liable to deliver the project assets to the investment agent (on behalf of the banks) on time and to specification. The wakala or procurement contract does not need to contain the detailed specifications of the project assets, but will usually cross refer to the specifications set out in the EPC contract.

- Ijara

As mentioned above, ijara (as part of a sale and lease- back arrangement) is regularly used in Islamic project financing of existing projects.

Using the traditional ijara (involving leasing of assets which are already in existence) would not provide the banks with a return during the construction phase of a greenfield project. As a result the istisna’ or procurement arrangement is usually combined with an ijara mawsufah fi al dhimmah (or “forward lease”) arrangement between the investment agent (on behalf of the banks) as lessor and the project company as lessee for the lease of the project assets, which will come into existence on the project completion date. Figures 79 and 80 depict the construction and operation phases, respectively, of such a product.

Although the ’actual’ lease period does not start until the project assets are delivered to the investment agent under the istisna’ or procurement contract, the project company pays ‘advance’ rental to ensure that the banks receive a return during the construction period. Since the ‘advance’ rental represents payment on account of the rental for a future ‘actual’ lease period, it is necessary for the ijara agreement to clearly state that the banks will reimburse all of the ‘advance’ rental received by them during the construction period, if the project assets are not delivered and therefore cannot be leased by the project company. It is important to note that the concept of a “forward lease” is not universally accepted by Shari’a scholars.

Multi-sourced projects

In multi-sourced projects where the Islamic tranche is only one part of the overall project financing package, all of the conventional and Islamic banks will enter into an inter-creditor agreement to regulate their relationship, and to ensure that they all share in any payments (whether voluntary or mandatory) on a pro rata basis, and that their facilities rank on a pari passu basis.

One important development in recent multi-sourced projects is the requirement from some Shari’a scholars that the proceeds of enforcement of security granted to the Islamic banks, or the sale proceeds of the Islamic leased assets can only be used to pay the principal, but not the interest component of the amounts due to the conventional banks. This has led to changes in the traditional enforcement payments waterfall to ensure compliance with Shari’a principles. The vibrancy of the Shuwaihat model has again been demonstrated on the recent financing for the Al Dur IWPP in Bahrain. This project, sponsored by Gulf Investment Corporation and GDF Suez, not only combined Islamic and conventional commercial debt, but also included a US$ 230 million facility from US Exim and insurance cover from KECI. As mentioned previously, this was also the first deal in the GCC region to use a mini perm structure, which gave the financing a tenor of eight years. The Shari’a-compliant tranche of US$ 300 million for Al Dur, provided by Al Rajhi, Banque Saudi Fransi.

Important structural considerations

- Ownership of project assets by a special purpose company

In order to remove the ownership risk from the banks and to deal with restrictions on foreign ownership of project assets (where there is participation in an Islamic project financing by international banks who are not al- lowed, under local law, to hold an ownership interest in the project assets), the ownership interest of the project assets in an istisna’ – Forward Lease arrangement, may be held by a special purpose company (SPC) owned by local banks (or their affiliates). Having the SPC hold the title to the project assets removes the direct link between the banks and the project assets, thus mitigating the effect of any asset ownership-related risk which the banks may otherwise face. The effectiveness of this structure will depend on the local laws of the country in which the project is located.

- Effect of total destruction of the project assets

A total loss of the leased project assets due, for example, to a natural catastrophe or an accident, gives rise to particular considerations in the context of an Islamically financed project. The commonly accepted view is that if the leased assets suffer a total loss and are therefore no longer capable of economic use by the lessee (project company), then the obligation to pay rent ceases upon the occurrence of the total loss event. As a result, any purchase undertaking in respect of the assets will also become ineffective. In order to deal with this situation, Shari’a scholars have agreed to allow the banks to appoint the project company as their service provider and for it to put in place and maintain insurances for the full replacement value of the project assets. In case of a total loss, the project company (as service provider) will be obliged to provide the banks with the proceeds of the insurance. If the proceeds are less than the full replacement value of the assets, the project company (as service provider) will have failed to satisfy its strict liability, and will be liable to indemnify the banks for any shortfall.

- Voluntary and mandatory prepayment

Unlike conventional financing, the project company can- not simply make a partial or full prepayment of the Is- lamic financing by issuing a notice of prepayment. The project company will instead need to exercise its rights under a call option (usually granted to it under the terms of a sale undertaking) to purchase from the banks (as lessors) some or all of the project’s assets, or an interest therein. In order to avoid the arrangement being considered as a sale and purchase of assets in the future, the arrangement is usually structured as a unilateral promise to sell given by the banks to the project company.

In the event that the project company is in material breach of its obligations under the financing arrangements, or the banks are required by law to cease their relationship with the project company, then (as in a conventional financing) the banks will have the right to require the project company to prepay the financing. The mechanism by which the banks will exercise their rights in such circumstances will be by exercising a put option (usually granted to them by the project company under the terms of a purchase undertaking), requiring the project company to purchase the project assets from the banks (as lessors). The exercise price will usually be the full amount outstanding under the Islamic project finance facility, and the banks will have the right to enforce against and liquidate any security given to them by the project.

Areas of Development

One of the principal growth areas of Islamic finance in recent years has been the issuance of sukuk. Given the asset-based nature of project finance, it is rather sur- prising that, to date, sukuk have not been used as a means of raising capital for projects. There is anecdotal evidence to suggest that sponsors will increasingly seek to incorporate the issuance of sukuk in their financing plans. Moreover, the introduction by Tadawul66 of a sukuk trading platform is likely to lead to increased liquidity in that sector during the coming years.