Introduction

Against the rapid development of Islamic finance, human capital is the defining factor in the sustained growth of the industry. As Islamic finance continues to make inroads into mainstream finance globally, this has created a huge demand for qualified finance professionals with the knowledge and technical skills in Islamic banking and finance. According to Mohammad Akram Laldin who sits on the Malaysian Central Bank’s Shari’a Advisory Council “the Islamic finance sector is growing faster than the supply of talent the industry has to continue its efforts to bridge the gap.” The exponential growth of the Islamic finance industry globally and regionally has also resulted in a global talent shortage for qualified finance professionals who are grounded in their understanding of the substance and form of Islamic finance.

The growing talent shortage in turn is creating intense competition for qualified Islamic finance professionals as they become a rare commodity. And as the industry moves up the value chain, persistent talent shortage will curb the development of the Islamic finance industry with Islamic financial institutions finding their cost going up in the short term. This shortage can only become more acute if not addressed in a holistic manner. The underlying issue for Islamic finance in its quest to boost international competitiveness is human capital to support this expansion and growth. But having sufficient qualified Islamic finance professionals continues to be the weakest link in Islamic finance.

Talent Landscape

The Islamic finance industry has been feeling the pressure of a skills shortage. It is estimated that a total of 50,000 professionals will be needed to fill up various positions in Islamic financial institutions globally in the

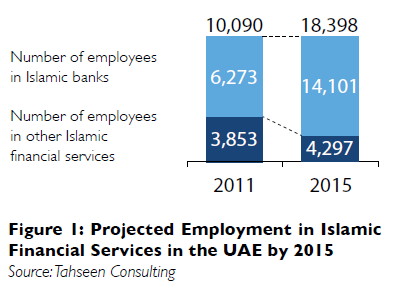

next five years. In the UAE, it is estimated that by 2015, the size of employment in the Islamic finance industry in the UAE will increase to 18,398 of which about 77% will be employed in the Islamic banking sector (Figure 1).

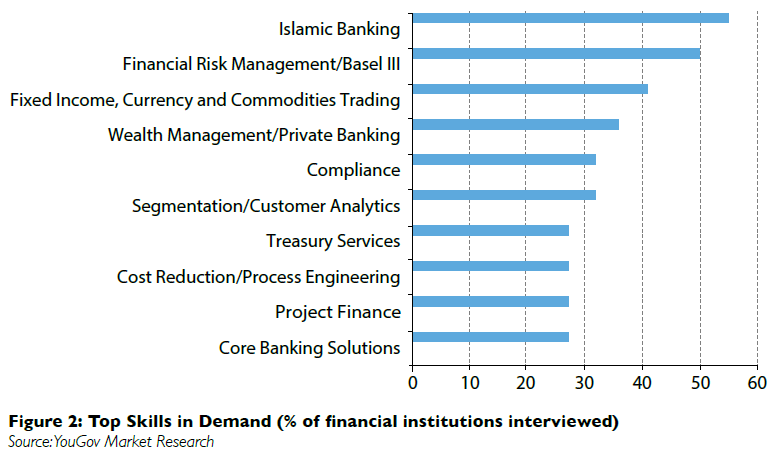

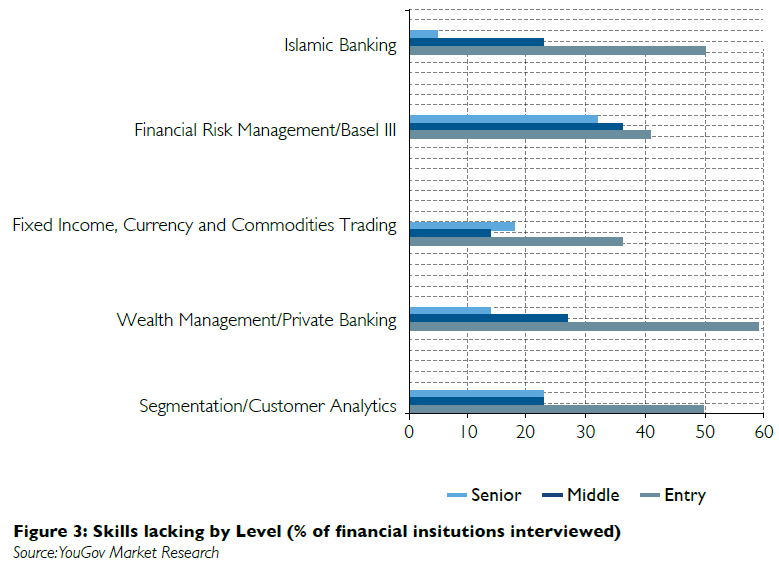

A recent Workforce Planning Study revealed that Islamic banking skills are the most demanded from banks in the GCC, particularly at the entry-level. Of the 60 banks surveyed, 50% of banks said that they find it difficult to hire graduates of Islamic banking for entry-level positions. Another 23% reported difficulty in hiring Islamic finance professionals to fill in mid-level positions whilst 5% of the banks reported that they find it hard to hire qualified Islamic bankers for senior positions.

Malaysia which has one of the most advanced Islamic finance industries in the world is facing the same talent crunch. In the Financial Sector Blueprint (2011- 2020) released by the Central Bank of Malaysia, an additional 56,000 finance professionals will be needed to support the financial services industry of which 40% is needed to serve the Islamic finance sector. Specific talent in new areas such as Islamic wealth management, Shari’a advisory, Islamic corporate finance and Islamic investment advisory services will be required to support the industry’s double-digit growth. The Islamic finance industry currently employs about 16,000 professionals or 11% of the total financial services industry employment. Takaful, a growing segment of the Islamic finance industry has about 131,000 agents serving the growing demands for Shari’a-compliant offerings in the country.

With the enactment of the recent Islamic Financial Services Act (IFSA), staff pinching, especially amongst takaful operators, is expected to rise as they are now required to relinquish their composite licenses and conduct their life and general insurance businesses under separate units or subsidiaries. This will have a huge impact on the recruitment and retention of new and existing talent within the takaful sector. The takaful sector is facing a critical talent shortage as qualified actuaries are not only limited but prefer to work in other more developed financial centres such as Hong Kong and Singapore. By 2016, the detoxification of insurance premiums will be a game changer for this sector and new sets of skills will be required for both actuaries and underwriters. Unlike the UAE, Malaysia’s talent war extends beyond its own shores as it has become a major exporter of talent. Islamic financial institutions are not only losing talent due to pinching amongst themselves but to other jurisdictions as well as other industries. Top talent from Malaysia, which is considered as a mature Islamic finance market, are being lured to countries in the GCC which offers more attractive remuneration package and tax-free status.

The Islamic finance industry in Indonesia has been experiencing high double-digit growth, outpacing the conventional banking sector’s growth of 16.7% per year. Like its other counterparts, Indonesia is also facing a critical talent paradox as the Islamic finance industry is experiencing a talent shortage of about 37,000 professionals. Industry estimates revealed that an additional 17,000 Islamic professionals will be needed in the next three years as the industry continues to record high-level growth at the back of strong economic growth. Similar to Malay- sia, the majority of finance professionals working in Islamic financial institutions are conventionally trained. This rings true for top positions in many Islamic banks where hiring of conventional finance personnel is prevalent. In Indonesia, only about 10% of employees in Islamic banks have relevant background knowledge of Shari’a whilst the majority are conventionally trained bankers.

Causes of Human Capital Shortages

In this section, we present several of the most obvious reasons for the human capital challenge in the Islamic finance industry.

- Issues with Islamic Finance Education

One cause of human capital deficiency is the short history of Islamic finance education. Many current faculty members were trained in conventional finance or western economics. This affects their ability to develop students’ understanding of Islamic finance. Islamic finance is loaded with old Arabic terminology which can be confusing even to native speakers of Arabic. It requires individuals proficient in Islamic finance to simplify concepts. Currently, there are very few textbooks on the subject. To make things worse, the focus on research is poor which affects the graduates’ ability to innovate once in the job market.

According to Dr. Humayon Dar, the gulf between academia and industry is playing a trick, as many of the graduates of universities (including INCEIF) get confused by their own professors who seem not to be fully convinced by the practice of Islamic banking and finance. He points out the discontent of the Islamic banking and finance industry with academic institutions and other specialized institutions offering instruction in this field is caused by the lack of practical experience of some Islamic finance professors. He advises the authorities to invest in exposing academicians to the practical side of Islamic banking and finance. Interestingly, he suggests that for a successful career in Islamic banking and finance, a strong Shari’a and law background is helpful as Shari’a and law professors understand the practice of Islamic banking and finance better than finance and economics professors.

- Issues with Islamic Finance Training Programs

Aside from traditional university education, Islamic finance human capital preparation mechanisms range from face-to-face training, published guidebooks and online courses. Ethica Institute (2011) opines that Islamic finance training programs range from “excellent to illegal”, arguing that some training programs lack credibility. The same source adds that the scholar who approves a training program should demonstrate a deep knowledge of the Shari’a as confirmed by peer reviews in addition to having practical experience in banking and finance.

Training programs are being criticized for the following reasons:

- i) When certifying their programs they rely upon scholars who merely regurgitate AAOIFI’s rulings instead of having the skill of analyzing classical texts and developing products that meet modern consumer needs.

- Confusing newcomers with an overload of theories and multiple standards, such as discussing Islamic financial products while explaining that they are controversial and rejected by most

- Lacking the competence needed for dealing with students’ skepticism concerning the credibility of Islamic finance. Many students view Islamic finance as conventional finance wrapped in Islamic terminology.

- Allocating a disproportionate amount of resources to marketing and distribution expense ac- counts rather than to content development and updates.

- Diverse Shari’a Interpretations hence Limitation In Cross-Border Skill-Transfer

There are different schools of thought resulting in diverse Shari’a interpretations with varying levels of strictness, particularly between Malaysia and GCC countries. Consequently, there is a limitation in cross-border skill-transfer, which makes it difficult for graduates to seek jobs in other countries. However, some experts disagree with viewing the Shari’a interpretation of diversity as a shortcoming. For instance, Rushdi Siddiqui believes that most industries begin with fragmentation, followed by coordination, and consolidation. He opines that the Islamic finance industry is still in the fragmentation phase, thus the current differences in interpretation are to be expected (The Prospect Group 2013a).

Iqbal Khan, the CEO of Fajr Capital, notes that there are currently more than 6,000 fatwas that concern Islamic finance and Islamic banking, with a general agreement on 95% of the Shari’a standards, hence the 5% difference leaves space for innovation, new products, and new ideas to be accommodated (The Prospect Group 2013b). However, calls for the standardization of Shari’a interpretation remain strong (Ghoul 2011).

- Cultural Differences

It is believed that cultural and language differences are contributing to the human capital deficiency. For instance some top Malaysian Islamic finance graduates do not stay very long in the positions that they accept in the GCC countries which are considered to be less open to foreigners. In addition, Malaysia is currently making an effort to lure its Islamic finance graduates back home, which could escalate the shortage problem for GCC.

- Placement Challenges

Daud Abdullah, President and CEO of INCEIF commented about employment concerns within the Islamic financial sector, and admitted that helping graduates to find jobs is a challenge (The Prospect Group 2012). Abdullah states a couple of reasons for the placement challenges, namely the fact that the graduates do not all have “the right quality” in terms of the education they have received, and that they are generally not flexible in terms of the type and place of work that they are willing to accept.

Naturally, placement problems are worse in countries where Islamic financial institutions are less common, in contrast with mature markets such as Malaysia where top quality graduates do not have a problem in finding employment. To resolve placement challenges INCEIF plans on establishing an alumni association and strengthening relationships with the industry in order to help place future graduates.

- Newly Established Educational Institutions Lack Recognition

Newly established educational institutions have not yet established a track record, which puts their graduates at a major disadvantage.

The Calibre of Current Islamic Finance Graduates

The shortage of Islamic finance professionals is caused neither by the lack of educational programs nor by the short supply of Islamic finance graduates; it is instead a symptom of the inadequacy of training and the deficient educational preparation of professionals. UK Chancellor of the Exchequer, Mr. George Osborne, bragged that the UK “has more than a dozen universities or business schools offering executive courses in Islamic finance.” criticisms of the quality of education offered by these institutions. The alleged high variability in the standards of Islamic finance centers in UK universities undermines a recent pledge by the government in the UK to be a leader of Islamic finance in the West. Regrettably, countries and universities around the world will continue to claim to be the leaders until a body for accreditation is created, followed by a university ranking system which is similar to that which is common in conventional education.

According to Ghoul (2013), graduates with Islamic finance or Islamic law degrees from universities in Muslim countries or Western countries currently suffer from a mismatch between the education that they have received and the needs of employers. The Islamic finance education system has been described as very ordinary and too narrow with very few courses on economics, finance, and accounting that are based on Islamic principles. To make things worse, university programs that train Shari’a scholars do not allow for specializing in economics, finance, financial and commercial law (Park- er 2007). Sayd Farook, Global Head of Islamic Capital Markets for Thomson Reuters, reports having had the opportunity to hire about 30 Islamic finance professionals over the past three years from across the world. He laments the fact that the current calibre of graduates “is still not up to standard”. Farook states that although most of these people did have diplomas and qualifications in Islamic finance, he had more success in hiring people who did not hold degrees in Islamic finance. In sharp contrast, Islamic finance graduates complain that there is a shortage of positions. It could be argued that in countries such as Singapore which has a limited number of Islamic financial institutions there isn’t a lack of talent, there’s just a lack of opportunities.

With respect to Shari’a scholars, Siddiqi (2006) states that there is a lack of proper institutional arrangements for training Shari’a scholars as far as conducting fundamental research. This issue has resulted in frequent in- stances of “malfunction” causing concern in the market and increasing the chance of Islamic financial products being rejected by consumers. Some scholars may be stagnant in terms of their knowledge and some could give the wrong advice. Farook and Farooq (2013) opine that the Islamic finance industry urgently needs to scrutinize the qualification and preparation of scholars “so that the future generation of scholars and experts can be reared and prepared more systematically”. Most importantly the authors criticize traditional religious thinking, that what is needed is an observance and application of the accumulated body of knowledge since this hinders innovative thinking.

Talent War in Islamic Finance

The phrase “War for Talent” was first coined by Steven Hankin of McKinsey & Company in 1997 to describe the phenomenon of talent shortage experienced by organizations. This phrase has since been echoed many times and has now taken a new global shape. After two decades, this war continues unabated as organizations engage in fierce competition to attract, hire and retain the very best people. The degree of this talent war differs between mature and immature Islamic finance markets although both markets face similar hiring issues – hiring top talent who are skilled in finance and banking as well as being well-grounded in the Shari’a complexities of Islamic finance.

If the escalating talent shortages are not addressed properly, this could have serious implications for the industry’s sustainable growth. The talent war in the Islamic finance industry is not showing any sign of waning, with the increasing shortage of talent affecting all sectors in the financial services industry. This is manifested by a number of sweeping changes. Among the fundamental forces fuelling the talent war are changing workforce demographics, generational differences and the growth potential of Asian economies.

The most fundamental driver of workforce diversity today is the changing workforce demographics resulting in a much broader range of ages in all professions. As the ‘baby boomer generation ages, organizations face the problem of having a significant part of the workforce retiring at the same time. This translates into two unique challenges – the employees and their implicit knowledge will leave the companies; and the recruitment of a qualified workforce is hampered by skill shortages or talent constraints. Several professions in the financial industry such as accounting and auditing are now clearly feeling the effects of employee retirement and the difficulty in sourcing new talent.

As a result of this development, generational diversity has become a new reality. The workforce today is made up of 4 unique generations (Traditionalist, Baby Boomers, Generation X and Generation Y). Each of these four generations brings its unique stamp to the workforce and is guided by a different set of values, life experiences, beliefs, expectations and attitudes. With multiple generations actively engaged in the workforce comes a new set of challenges for employers. Organizations that recognize, leverage, and bridge the generational divide will gain a competitive advantage in the talent market.

Further complicating the generational diversity is the change in attitude among the generations of workers who will remain in the labour market over the next few decades. In today’s constantly changing workplace, one thing remains constant: a younger generation of workers who have vastly different expectations, needs and patterns of behaviour that differ markedly from prior generations. As the baby boomers ease into retirement age, employers must learn to understand the motivations and desires of the younger generation of employees who seem to be more motivated by personal fulfilment opportunities on the job than by traditional monetary rewards.

The talent market is now more competitive than ever before and is expected to intensify further in the coming decades. In a knowledge-driven economy, the demand for highly skilled Islamic finance professionals is on the rise. Although the demand may at times decline with financial downturns, the rising trend will continue to linger in the longer run. This remains true in the wake of the global financial crisis. At the height of the crisis, many financial institutions downsized their operations and staff at the expense of further expansion. As the financial sector scrambles back to its feet, talent shortage and competition among financial institutions to expand and rebuild their operations, particularly so in Asia in their intense quest to piggyback on the growth potential of the region, has set off the talent war with Asia as the main battleground.

Attracting Youth

Notwithstanding the lack of qualified people, the Islamic finance industry has not been able to capture the hearts and minds of the youth, more commonly known as Generation Y (Gen Y). In order to get the talent needed, Islamic financial institutions must focus on what talent

needs and key to Islamic finance’s talent dilemma is attracting Gen Y. Many industry observers agreed that the industry is not attractive to young professionals as it is viewed as too rigid and highly regulated.

Gen Y has been referred to by many names – millennial, echo boomers, me first, first digital and net generation. This cohort of individuals is born between 1978 and 1995. Unlike the generations before them, this group of employees comes with pre-honed technology skills and ingrained multi-tasking skills (refer to Table 1). However, they remain an enigma to many organizations. Lindsay Pollack, author and Gen Y theorist, said that when it comes to dealing with Gen Y, “what used to be common sense isn’t common sense anymore”. She suggests that organizations to rethink their approach to attracting and training Gen Y.

Gen Y is the largest age group to emerge since the baby boom generation. As this generation grows to become a significant proportion of the workforce, recognizing the unique forces that shape this misunderstood generation requires insights and a fine sense of balance. As Gen Y is set to become the largest proportion of the workforce, the primary source of competitive differentiation for organizations will be human capital.

This is a uniquely global phenomenon and affects developed as well as emerging economies; conventional as well as Islamic finance. Hence, it is strategically imperative for organizations to understand the environmental influences of Gen Y including understanding who they are and what has defined their experience. This is particularly more important and relevant for the Islamic financial industry as Mercer’s survey on Total Remuneration reported that finance jobs are one of the top three categories of ‘jobs most difficult to retain’.

Unlock the Values

According to the Robert Half survey of 300 CFOs and finance directors, nearly half of employees said Gen Y were the hardest to retain compared with Gen X and baby boomers. More than 60% of them attributed this to high expectations among Gen Y employees for career advancement, expectations for remunerations and work-life balance. A joint report by ACCA and Mercer offers interesting insights into the aspirations and traits of Gen Y finance professionals. The report highlighted that a dynamic career progression is key to attracting, developing and retaining them. And this entails ambitious, fluid and continuously evolving career paths.

It is even more interesting to note that almost half of Gen Y finance professionals surveyed had diverging career expectations. Dubbed as “a tale of two career paths”, the report contended that 40% of young finance professionals wished to pursue a traditional career in finance whilst the rest are seeking careers outside main- stream finance roles (see Table 1).

Those who want to remain in finance are looking for vertical career progression and to develop a specialization in similar or different areas in the finance field. Gen Y professionals seeking non-traditional finance roles prefer to build their financial management capacity in business and eventually expand their careers beyond their current finance functions. The findings of the survey have huge implications on the strategies of financial institutions on talent management. Gen Y expects institutions to provide a number of career options as opposed to specializing in specific areas of finance.

| Silent Generation | Baby Boomers | Generation X | Generations Y | |

| Who they are | Born between 1925-1945 | Born between 1946-1964 | Born between 1965 – 1977 | Born between 1978-1995 |

| Tagline(s) | “When in command, take charge. When in doubt, do what’s right.” | • “Live to work”• “Willing to go the extra mile” for an employer | • “Work to live”• “Original latchkey kids”• “Vanguard of the free agent workforce” | “Like Xers on steroids” |

| Values | • Work itself and the peo- ple they work with.• Command-and-control mindset | • Respect, empowerment, challenge and growth | • Work/life balance;family• Individualism; Entrepreneurial• Technology; creativity• Diversity and transparency | • Immediate feedback and payoff• Hard work pays off.• Technology; creativity |

| Preferences | • To work with strong leaders with proven track records | • Work environment con- ducive to results-orien- tation• Job stability and security | • Demands immediate rewards for contributions• Flexibility, money and portable benefits, harmonious work environments and fulfillment• Work environment conducive to relationship building• Independent work vs teams, although comfortable in groups | • High expectations of personal and financial success• Seek challenging, meaningful work that impacts their world• Do not like being treated as the new kid on the block |

| Relationship to or with Employer | Willing to learn new skills to be more effective in their current job | Include them indecision-making, give clear goals and responsibilities and then get out of their way and let them getthe job done” | • Always looking for “bigger/better deal”• Less loyalty to an employer; not intimidated by authority• More willing to make lateral moves to add to their skill sets• More self-reliant and more self-directed | • Most high-maintenance generation to ever enter the work force• Little loyalty to an employer; not intimidated by authority |

Table 1: Four Generations at Work

Source: Bruce Tulgan; Rainmaker Thinking

However, many institutions and organizations are still wrapping their heads around what makes Gen Y ticks and how to effectively engage and leverage the newest entrants to the workplace. Why should organizations care? A thorough understanding what shapes Gen Y is valuable to employers if they want to successfully attract, develop and retain this newest talent. Some of the major characteristics of Gen Y are described below:

- Gen Y is the first generation to grow up with technology and rely on it to perform their work The explosion of technology has shaped Gen Y’s values and attitudes both in their personal and work life. Being digital native, this tech-savvy workforce is accustomed to real-time information anytime and anywhere. For them, gadgets like iPad, tablets and smartphones or android phones are regarded as status symbols. Armed with these high-tech gadgets, Gen Y is plugged-in 24 hours a day, 7 days a week and is very good at multi-tasking – they talk on the phone while surfing on the net and text while listening to music. This ability to multi-task can challenge the way baby boomers perceive their younger colleagues. And because of their deep reliance on technology, they believe in workplace flexibility and that they should be evaluated on their work output rather than on how, when or where the work is being done.

- Gen Y’s life is on social networks. Social media plays a dominant role in Gen Y’s personal and professional Unlike other demographic cohorts who use social networking mainly for entertaining and socializing, Gen Y is using this platform in more diverse ways. Between Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn and WhatsApp in Asia, these digital natives use social media sites to connect and communicate with their friends, colleagues and superiors. To them, social media goes beyond making contacts, updating statuses and discussing life as well as topics of interest. Social and professional networking sites have evolved to become a platform for them to expand their professional network and mine for job prospects. Gen Y is inadvertently blending social and professional life; blurring the lines between the two. The Cisco’s Connected World Technology Report revealed that more than half of Gen Y respondents said that they “will not accept a job that bans social media”. The fact that Gen Y prioritized social media access at work over salary speaks volumes, but the financial services industry is not responding to this need. Most banks ban social media as they are concerned about open access to their IT infrastructure.

- Gen Y puts personal fulfilment ahead of In another study, personal growth and work-life balance were found to be important considerations over pay rates for Gen Y when choosing a job. These results, as reported by Kelly Global Workforce Index (KGWI) survey, provide a startling revelation on the motivations of Gen Y. They have a deep-seated desire for work to be personally enriching and rewarding. More than any other generation, Gen Y professionals are attuned to the bigger picture; seeing everything as connected. They want to see how their work contributes to the larger corporate objectives. Essentially, Gen Y seeks greater engagement and “meaning” from their work. The Asian culture of working long hours and long-term loyalty is also fast becoming queer as Gen Y values work-life balance over career. Like their peers in other regions, Gen Ys in Asia are rejecting the traditional “work hard and get rich” mentality in favour of a lifestyle devoted to personal satisfaction.

- Gen Y is achievement-oriented. Gen Y professionals grew up with an entitlement mindset. Jean Twenge, the author of the book Generation Me, describes them as “smart, brash, arrogant, and endowed with a commanding sense of entitlement’. Nurtured and pampered by parents to believe in themselves and their abilities, Gen Y-ers are confident with strong self-esteem. Such strong self-confidence, she argues, “is what allows them to accomplish great things and can keep companies progressing”. Gen Y’s so-called ‘helicopter parents” tend to hover over their kids, dote on them, and protect them from criticism and disappointment with constant positive As a result of such upbringing, these children display an abundance of self-confidence and are very ambitious. Likewise, they are particularly achievement-oriented, thanks to video games that have taught them to constantly advance to the next level.

- Gen Y craves for immediate feedback. The same electronic games that they grew up with also trained them to receive immediate feedback, rewards and recognition on their performance. In the workplace, they favor the same constant and consistent feedback from their managers but in a non-formal fashion. In this sense, the traditional annual, semi-annual or even quarterly performance review is not effective with Gen In a report produced by Kelly Services titled Gen Y at Work, employers are recommended to “provide regular feedback sessions and lesser performance review cycles supported by mentoring or coaching” to retain Gen Y at the workplace.

With Gen Y employees poised to become future managers and leaders, employers and HR practitioners need to have a better understanding of how to work with them and manage them. It is also important to develop effective strategies to attract, retain and motivate Gen Y employees from the start. An important step to attract Gen Y finance professionals is to clearly communicate with them what career paths and associated timelines are available. Since lifestyle is also an essential consideration, an organization’s brand value is the key to attracting these young finance professionals. In developing these young professionals, organizations should provide a host of well-coordinated opportunities for experiential learning. Organizations should also design learning interventions that are most suited to Gen Y based on their unique predilections. The final challenge is retention. The key here is to offer a compelling career that matches their dynamic and trendy lifestyles.

Talent Economy

At the heart of the talent war is the presence of inflated wages. The scramble for qualified Islamic finance professionals globally is pushing up the cost of attracting and retaining talent. The talent crunch has driven up wages and narrowed the salary gaps. In Malaysia, for example, a 20% salary hike is currently being experienced by the Islamic financial industry. Talent pinching has resulted in higher wages as Islamic financial institutions are willing to pay premium wages to attract much-needed qualified Islamic finance professionals. Although this may be beneficial in to the financial institutions in the short run, it can have a detrimental effect to the whole industry in the long run especially when there is no or little improvement in productivity and efficiency. As the war for talent intensifies and demand for talent continues to outstrip supply; Islamic financial institutions are caught in a “catching up” game to fill talent scarcity.

In Malaysia, Shari’a professionals’ salary is on par with other professionals. Employees in information and communication technology (ICT), accounting and finance, administration, marketing, investment and other industries with the same number of years in experience (five to 10 years) and qualification levels (basic degree or Master’s) have similar salaries. But in the banking and financial industry itself, the salary scale is on the higher bracket of middle management.

According to Robert Walters Global Salary Survey 2014 for Malaysia, the Islamic financial services industry is expected to see salary increments of between 15% to 20% as the job market becomes more and more employee-driven. As the industry matures, key areas such as Islamic asset management and Islamic wealth management will require individuals with specialized skills and experience in the areas of equities and fixed income. The Islamic finance industry will also be on a hiring spree for corporate finance specialists with qualified Senior Personnel status.

As the Islamic finance industry continues to draw tremendous double-digit growth, the war for talent is reaching new heights with Islamic financial institutions embracing more creative talent management practices in terms of sourcing, recruiting and retaining finance professionals. According to ACCA, some of the key retention strategies adopted by financial institutions include realigning salary packages to current market rates, offering better career development opportunities and pro- viding flexible work schedules. The global economy has brought about a paradigm shift in talent management as workforces are increasingly mobile, have highly transferable skills and are technologically savvy. If talent is not nurtured and managed appropriately, the brain drain effect could be detrimental to long-term growth. The bottom line is that to win the war for talent, Islamic finance institutions must understand the current and future needs of the workforce. This requires taking a multi-faceted approach in recruiting, retaining and developing talent for the Islamic finance industry.

Recent Efforts to Resolve Human Capital Challenges

As far as Shari’a scholars are concerned, Malaysia’s Securities Commission is studying the development of an accreditation program for Islamic scholars. This project is at the “exploratory stage” and is projected to take at least three years. Along the same line, The Association of Shari’a scholars in Islamic Finance (ASSIF), a British-registered charity, is currently making an effort to address the lack of a clear, commonly recognized set of qualifications for Shari’a scholars.

Similar efforts are being made by ASAS which is a Malaysian-based Association of Shari’a Advisers in Islamic Finance, created in April of 2011. It had 60 members in 2012 and has been asking its members to sign up to a code of ethics. It is attempting to revamp the Shari’a advisor profession by creating a test for the financial literacy of scholars, offering guidance on issues such as how to appoint Shari’a boards and address potential conflicts of interest, developing a global code of ethics, in addition to improving standards through scholar training programs.

Concerning meeting the regular staff needs of the Islamic finance industry, careful strategizing from universities and governments is required. In Malaysia, there have been major efforts to develop human capital and the intellectual reservoir needed for sustaining the development of Islamic finance. The country has made talent development in the financial sector a strategic objective and a top priority and it is approaching this in a ‘holistic manner’, across the spectrum of the financial

Recommendations from the Industry

Islamic Finance Education

Muhammad Zubair Mughal, Chief Executive Officer of AlHuda Centre of Islamic Banking and Finance, recommends several approaches that could be adopted in order to educate masses in the field of Islamic banking and finance. These are university-level masters on Islamic banking and finance, postgraduate diplomas and certificate courses on different specialized topics, online programs, workshops, training and publications.

Shari’a Scholars

Farooq and Farooq(2013) recommend advanced graduate education programs which have to be constantly adapted to account for changes in Islamic scholarship as they tackle market developments. Continuing research and peer-evaluation mechanisms are also suggested.

Placement

Islamic finance educational institutions should aim to educate people who can work in both Islamic as well as conventional financial institutions. Geraci (2013) interviewed Simon Archer, author and Islamic finance professor at the ICMA Centre, who pointed out that the contents of the ICMA Centre’s Master’s degree in Islamic banking and Islamic finance (IBIF) is 30% Islamic and 70% conventional. Most surprisingly, Professor Archer points out that Islamic finance graduates should be willing to gain experience in the conventional sector to start with due to the smaller size of the Islamic financial sector, or they could work for a central bank or another supervisory body which supervises Islamic financial institutions.

Program Design

Ethica Institute (2011) argues that course materials and training programs should be based on AAOIFI’s latest Shari’a standards, and that the training content should result from a collaborative effort between bankers and Shari’a scholars. The next step requires a third party to verify and testify that the certification exams are consistent with Shari’a standards. On the other hand, Rashid Mahboob, Senior VP (Customer Excellence) at Dubai Islamic Bank, opines that universities and training providers must refine their programs and courses to support the sector by equipping young talent with the level of specialism and sophistication that is required by employers. Mahboob also urged employers in the Islamic finance industry to provide genuine on-the-job training (Vizcaino 2013).

Services industry (Zeti 2011). Malaysia’s Prime Minister Abdul Razak established the ‘Economic Transformation Program’ which aims to transform Malaysia into one of the world’s leading Islamic finance education hubs.

Another example of Malaysia’s Islamic finance education efforts consists of developments on three fronts thanks to efforts by Bank Negara Malaysia: education is handled by INCEIF; training is handled by the Islamic Banking and Finance Institute of Malaysia (IBFIM), whereas Shari’a research is the responsibility of International Shari’a Research Academy (ISRA) which is housed within INCEIF. 619 Master’s and doctoral degree holders in Islamic finance have graduated since 2007 from INCEIF.

The mission of INCEIF’s doctoral program is to balance theory and practice by developing the research skills of its graduates. Students are given two options: if they have practical experience in the Islamic finance industry they could get a PhD through research, otherwise they could sit through courses followed by a research dissertation. IBFIM focuses on vocational training leading to various Islamic finance certificates, in addition to serving as consultants to help banks and firms be- come Shari’a compliant (Epstein 2013).

In the United Kingdom the government has been taking various measures to maintain the country’s leading position in the West in the Islamic finance industry as well as education. It has created a task force whose objective is to support the promotion of UK academic institutions that offer Islamic finance education programs abroad and to encourage engagement and links with partners in Muslim-majority countries. The introduction of an accreditation system for Islamic finance education as well as the establishment of a regulatory body for training providers are two additional objectives of the task force, according to Warsi (2013).

A very recent development is an initiative which was announced on December 9, 2013, aiming to promote quality learning in the Islamic financial service industry. The Finance Accreditation Agency (FAA) is an organization supported by Bank Negara Malaysia and the Securities Commission Malaysia. It has signed a cooperation agreement with the Deloitte Islamic Finance Knowledge Centre (IFKC). This agreement represents a roadmap for enhancing the quality of education and training in Islamic finance. Quality Assurance and Accreditation (QAA) in Islamic Finance Executive Education is the initiative’s objective. Deloitte IFKC professional training programs will be benchmarked against best practices and reviewed by international experts around the world.

Building a Talent pool in Islamic finance

Talent is required to support the growth of the Islamic financial industry which is expected to surpass the US$2 trillion mark. While the growth of the Islamic financial industry is projected to maintain its double-digit growth, growing a talented workforce to support the industry’s expansion represents a challenge that requires a ‘blue ocean’ strategic approach in developing a deep and broad talent pool. The success of human capital initiatives is tied directly to the ability to create enduring public-private collaborations among industry, academia, training organizations, workforce development organizations, professional bodies/associations, research institutions and government in order to address critical issues in human capital development of the Islamic financial services industry. Such collaborative efforts would not only result in a new understanding of industry needs but also the emergence of initiatives to meet these evolving requirements. Hence, if the industry’s future talent needs are to be met, all stakeholders need to be more effective in identifying ways to collaborate. Although the significant focus has been directed at creating institutional arrangements towards talent development for all levels within the Islamic financial industry, more holistic and concrete policies are needed particularly in four key areas out- lined below:

Improve Communication and Coordination between Industry and Higher Education

More communication and coordination is needed between the industry and institutions of higher learning to ensure that graduates are well-prepared to take advantage of opportunities in a highly dynamic Islamic finance industry and employers must provide roadmaps of development to ensure talent is retained by the sector. Al- though universities are doing an excellent job in turning out good graduates, they need to be more responsive to the needs of the industry in their curricula development. The current independent efforts of individual institutions, both public and private, are insufficient to meet the collective needs of the financial industry as it grows and evolves in tandem with the transformation that is taking shape within the country and Asia more generally.

Limited communication and lack of effective coordination between industry and academia has steadily widened the gap between the demand and supply of skilled Islamic finance professionals in the industry. It is often claimed that graduates provided by universities these days are not up to the mark and lack market-driven skills. A closer relationship between academia and industry including better integration of higher education curricula must be encouraged. Towards this end, the establishment of an industrial curriculum committee or task force representing industry and higher learning institutions with the mandate of developing consensus on the education and training needs of the industry will be necessary. Apprenticeship opportunities could be created for school leavers to enter the industry. Research from more developed economies suggests that staff recruited via such an approach demonstrate greater loyalty to the hiring firm and sector. Detailed descriptions of the academic, industry-specific and interpersonal knowledge, competencies and attributes required for professionals entering or currently working in the industry need to be agreed upon. Such information is essential for universities and training providers if they are to produce more business-ready graduates.

Collaboration Beyond the Islamic Financial Industry

The FSBP also promotes greater collaboration and

The complementary growth of these two industries has resulted in more aggressive efforts in luring employees away from each other. Anecdotal evidence suggests that IT solution providers, software companies in particular, have experienced a brain drain of their IT specialists to other growing industries including financial services whose growth has created a demand for software engineers to develop innovative solutions for sector-specific solutions in the quest to improve efficiency and financial return. Hence, technology companies are not only competing for top talent with each other but also against big banks and financial institutions for the same talent. Recently, the three biggest associations representing the marketing communications industry in Malaysia announced their own graduate fellowship programme with a view of overcoming the shortage of quality talent. The advertising and marketing industry claims that they were losing top talent to other industries, particularly financial services due to competitive remuneration packages offered by the latter.

Collaborative efforts between sectors are important to ensure that talent is nurtured beyond the broader needs of a single sector. This would not only enable greater future availability of talent, but in the long term support future growth of related businesses. A paradigm shift is necessary as we move away from the view that talent, be it in finance or IT, is a resource that can simply be acquired. Instead, collaborative efforts to develop talent to meet the demand of all related sectors would only result in a more sustainable talent pipeline for the Islamic finance industry.

Workforce up-skilling

In order to meet the changing needs of Malaysia’s financial industry, stakeholders have to critically assess the current skills and competencies of their workforce. As local financial institutions expand beyond the Malaysian shore, the ability for these institutions to expand their client base to meet the increasing sophistication of customer demands depends critically on the quality of talent. The Financial Sector Blueprint (FSBP) envisaged that an additional 56,000 finance professionals will be needed in the next decade to support the financial industry’s role of a key enabler, catalyst and driver of Malaysia’s economic transformation and growth. But, coordination among various agencies beyond the Islamic financial services fraternity includes law, human resources, professional services, IT and corporate communications. Such initiatives are important in providing the breadth of talent development solutions for the industry and to curb the poaching of talent within and beyond the industry. Technology, for instance, has played an increasingly important role in the evolution of the financial services industry. The application of technology in the financial industry has created a new paradigm, one in which IT has moved beyond the add-on of a business function to be deeply embedded at the very core of day-to-day operations. As a result of this, Islamic financial institutions are constantly seeking IT professionals with knowledge and skills as they upgrade their technological capabilities. At the same time, IT solution providers are also experiencing a talent poaching challenge themselves it is not enough to have an adequate supply of talent. Talents must be equipped to handle the complexities of the evolving economic and financial landscape. With the Malaysian financial industry envisaged to evolve to be regional in orientation and internationally connected, the need to align talent competencies must be a key priority. At top management, financial institutions need to develop competitively focused competencies that align finance with business acumen and leadership.

Professional Standards

The global financial crisis had brought with it a number of challenges for economies and has dramatically changed the way business is conducted. This seismic shift in the financial landscape has placed new demands on Islamic finance professionals who are now expected to possess a broad range of skills and competence. However, the Islamic finance industry lacks a clear and globally recognized professional standard as well as qualifications for those working or entering the industry. The need for global professional standards is needed to enhance the quality of Islamic finance professionals, provide confidence and reliability to the market and investors, and minimize risk for individuals and institutions. The two key strands of professionalism are standards and qualifications. Here, professional standards are important as they are the first steps to building a more highly qualified workforce as they ensure competency in a given profession. A key factor to professional standards is ongoing learning (so-called continuous professional development or CPD) which is important in building and maintaining a high degree of professionalism. But to be effective, CPD must be seen to go beyond box-ticking and be made part of standards of knowledge and behaviour.

Although education-based qualifications are essential, professional qualifications are increasingly being recognized by organizations as an effective means to ensure employees have relevant and up-to-date skills. The most overt feature of well-regarded professions such as medicine, engineering, law and accounting is professional qualifications. The professional capability of these professions is built through four key areas:

- On-the-job acquisition of skills and competence

- Continuous professional development that enhance advanced technical knowledge

- Inter-generational transfer of norms, ethics and behaviours either from working with or being mentored by experienced professionals

- Enforcement of codes of conduct in a weak regulated

The Islamic finance industry can take queue from these industries. Such professional standards and qualifications throughout the industry can only have a positive impact on its reputation and long-term standing in the eyes of consumers. An industry-wide professional standard that encompasses best practices in ethics, codes of conduct and professional development for those working in the industry will ensure the industry is seen to be fair and transparent. The Islamic finance industry has yet to mature into a profession in the same way as other well-recognized professions. But it is high time that measures are taken to ‘professionalize talent’ within the industry and make it more akin to the other great professions in society.

Leadership through the Establishment of an Islamic Finance Talent Council

Collaborative efforts between various agencies in both public and private sectors require a great deal of leadership, discussion, planning and most of all relationship-building and a common understanding of the challenges. Such efforts in up-skilling and building capability must be taken with a view towards strengthening the institutional capacity and framework of skills development. By driving the Islamic finance talent development agenda, the Council can provide a greater strategic focus and take a leadership role to support a more dynamic financial sector through the development of an effective human capital development framework for the industry. In this respect, the Council should be well-positioned with the resources and authority to take the lead in developing a national strategy. Leadership should also be drawn from the highest levels of government, the finance industry at large, institutions of higher learning, workforce development organizations and professional bodies/associations. Apart from engaging with relevant stakeholders in determining the short-term and long-term talent needs, the Council must also play an active role in attracting the best and brightest which will require curriculum development that links theory and practical-based skills. Promotion of the excitement of working in the sector and the lifestyle it can provide generations Y and Z are key if we are to succeed.

Conclusion

The Global Talent 2012 report released by Oxford Economics revealed a tectonic market shift – economic realignment, regulatory changes, demographic shifts, digital lifestyle – all are radically reshaping the financial services landscape. These visible trends have forced many financial institutions to engage in transformational initiatives when rethinking their business strategies and modus operandi. Correspondingly, this transformation requires repositioning and retraining talent skill sets across all levels of seniority. The report highlighted that digital knowledge, agile thinking, interpersonal and communication skills, and global operating capabilities are talent areas that will become increasingly important for today’s financial institutions. Retraining of the workforce to meet these changing talent needs must, however, be addressed holistically and collectively.

Collaboration and coordination between various industry stakeholders, as well as parties beyond the financial fraternity, are needed in developing qualifications that fill vital skill gaps emerging from the changing demands of the world of finance. Successful public-private partnerships of retraining the workforce should be emulated. Cisco, for example, has a strong track record of such partnerships through their Work Retraining Initiative programme which has shown to be successful in developing job skills programmes in broadband infrastructure, network security and health- care information technology. Accenture claims a 135% return on investment of its staff training function which the company has expanded in recent years.

The roles of government, industry and academia need revisiting. To move forward, all relevant stakeholders must first appreciate and recognize that current solutions in meeting talent demand are not filling the gaps that need to be plugged. Back to the burning question at hand. How can the industry find the required additional 50,000 Islamic finance professionals? What are the skills and competencies required of the new generation of finance professionals? Although there is no universal panacea, better collaboration between all stakeholders may well be able to address some of the urgent talent issues at hand.