INTRODUCTION

What is so innovative about IBF? All Islamic financial institutions do more or less what their conventional peers do. For example, Islamic banks accept deposits, offer credit to households and businesses, and invest in government and other fixed-income securities – all the functions that a conventional bank will otherwise do. If that was not enough, Islamic financial products are priced with reference to an interest-based benchmark, making them look like and behave like conventional financial products.

Takaful companies offer protections against adverse incidences (e.g., theft, fire and accidents), and collect contributions (i.e., premia) and entertain claims. Although they claim to be cooperative in nature but they share very few features with mutual organizations.

Takaful operations by and large remain in the spirit of conventional insurance.

Similarly, in Islamic fund management, a fund manager does more or less what other fund managers do. In case of an Islamic equity fund, t fund manager builds a portfolio of Shari’a-compliant stocks drawn from the same larger universe from where a conventional fund manager picks up their stocks. The dividends are paid out, management fee is charged, and other service providers get what they are supposed to get in the market. So the question arises what is this all fuss about IBF.

The real value proposition of IBF so far has been in terms of its emphasis on Shari’a compliance. IBF has emerged as an example of financial innovation whereby Shari’a principles relevant to business are applied to banking and finance to ensure that they conform to Islamic beliefs and teachings. In this respect a primary objective of Islamic financial innovation has so far been:

“Developing new financial products for the Islamic financial services industry, which replicate economic effects of the conventional products in a Shari’a-compliant way”.

A primary objective of Islamic financial innovation is to develop new financial products for the Islamic financial services industry, which replicate economic effects of the conventional products in a Shari’a-compliant way.

In other words, the efforts in the last four decades have primarily focused on making McDonald’s menu available to those who would eat only halal food. The brands like HSBC Amanah, Standard Chartered Saadiq, UBL Ameen, CIMB Islamic, Maybank Islamic, Mashreq Al-Islami and Bank Syariah Mandiri are not incidental. Their story is exactly the same as a Halal McDonald’s – same menu of products, same economic outcomes, similar pricing – nothing more nothing less.

One may rather cynically ask what is so new about Islamic financial products, after all they essentially replicate conventional products. In fact, despite huge progress in IBF in the last decade a vast majority of Muslims (estimated to be 75% of the global Muslim population) do not deem IBF significantly different from the existing conventional models and practices of banking and finance.

This chapter analyses innovation in IBF, with a view to suggest a future course of action for developing a new generation of Islamic financial products, which must differentiate IBF from the existing conventional practices of banking and finance.

Keeping aside the cynical view, there have been three significant innovations in IBF since its inception. These include:

- Murabaha (1970s)

- Sukuk (1990s)

- Wa’ad (2000s)

Murabaha in its pure form is no more than a cost-plus contract whereby a seller is required to disclose their profit (or cost) to the buyer. Such cost-plus contracts are frequently used in modern businesses for internal transfers or intra-company trade in large organizations. In the context of IBF, a specific form of murabaha is used (which is called murabaha lil amr bi-shira), which is then combined with a deferred payment sale contract (called bai’ mua’jjal). This type of murabaha allowed Islamic banks to offer financing to households and businesses. In fact, it is such a powerful tool that its variants are also used as part of liquidity management and hedging instruments used in the Islamic financial services industry.

Like classical murabaha, the historical use of sukuk was very different from its contemporary application.

A classical sakk was more or less a note issued in favour of its bearer allowing them to have a claim on an asset. The modern sukuk in their most frequently used form are examples of securitization whereby an asset is securitized to raise more capital without necessarily diluting shareholders’ equity in a going concern. This type of sukuk allowed governments and corporates to issue Islamic securities to raise Shari’a-compliant debt. Most recently, some banks have used more innovative structures to issue sukuk to raise Tier-II capital in anticipation of the future enforceability of Basel III (see, for example, entry on Malaysia in Chapter 3).

The use of wa’ad is perhaps the best example of an innovative use of a concept that has historically been marginal to juristic thinking. The use of wa’ad allowed Islamic banks and financial institutions to develop Islamic hedging instruments. Wa’ad has become so widely used in IBF now that there is hardly any Islamic financial structure where we do not find its applications.

It is safe to claim that without these three developments, it was perhaps impossible for the Islamic financial services industry to grow so quickly to attain the mark of US$2 trillion under management by the end of 2014 (as reported in this edition of GIFR).

Murabaha, sukuk and other wa’ad-based products (and all other Islamic financial products) meet the above-mentioned objective of Islamic financial innovation.

ISLAMIC FINANCIAL INNOVATION DEFINED

In a business context, innovation could be of two types:

- Product innovation; and

- Process

Product innovation entails designing, developing, producing and selling a new good or service to create a new market for it.

Islamic financial innovation may adequately be termed as an example of process innovation. Process innovation involves designing, developing, producing, marketing and selling a good or service (for which there already exists a well-defined market), in a more cost effective way to maximize profits of the business. In case of IBF, however, the costs of production happen to be higher than conventional banking and finance, i.e., most of Islamic financial products are not more cost effective when compared with their conventional counterparts. Although the price differential between Islamic and conventional products has narrowed down in the recent past, it cannot be denied that Islamic financial products in the beginning were significantly more expensive than their conventional equivalent.

“Systemic innovation in IBF entails developing a policy framework and a regulatory regime, which should aim at creating a completely independent and mutually exclusive playing field for Islamic financial institutions to offer new products that must be distinctly different from conventional financial products in their risk-return profiles and value proposition.”

After forty years of practice, a need is being felt that IBF should now start focusing on what may be termed as systemic innovation.

As shown in Figure 1, phase 1 of the IBF development involved process innovation (1970s- 2014). In phase 2 (proposed to be 2015-2020), Islamic financial institutions must start developing genuinely new financial products, adding a distinct economic value proposition to mere Shari’a compliance of their product offering. In phase 3 (which should ensue from 2021), Islamic financial services industry should aim at developing a financial system that must provide a credible and workable alternative to conventional financial system.

“Decisions taken by shareholders and management of some Islamic banks to drop the word Islamic from their names is indicative of conventionalization of IBF.”

If process innovation continues, a time will soon come when IBF will be completely conventionalized to become part of the existing (and admittedly evolving) financial system. There is some marginal kind of indication of this trend already on the horizon. Decisions taken by shareholders and management of some Islamic banks to drop the word Islamic from their names is indicative of conventionalization of IBF.

It is now a common talk at conferences and seminars on IBF, suggesting that it is the right time for Islamic financial institutions to stop emphasizing on their Islamic identity. Rather, this is argued, they should focus on capturing more market share by offering financial products with the features like better customer services, ease of location and convenience of delivery etc. These suggestions seem innocuous, per se. However, in a long-term context, they do not favor IBF that must attempt to develop a new more just and equitable model of banking and finance within an Islamic financial system that should in turn be part of an Islamic economic system.

It must be emphasized that innovation is a marginal process. Most examples of financial innovation merely represent a small incremental value. The process of innovation in IBF has also contributed marginally to the economic profiles of financial products. It is, therefore, not surprising that it has taken the Islamic financial services industry about 10 years to embrace the Islamic hedging instruments based on wa’ad structure, although wa’ad was already in use in IBF long before the advent of the said hedging instruments.

INGREDIENTS OF ISLAMIC FINANCIAL INNOVATION

There are four basic ingredients of Islamic financial innovation:

- In-depth Shari’a knowledge

- Legal structuring

- Access to cutting edge financial technology

- Deep understanding of market trends and needs

If any of the above ingredients is missing in the process of developing an Islamic financial product, it must be flawed in its application or in its final form. These four points are explained below with particular examples.

In-depth Shari’a Knowledge

Although a number of political, economic, cultural, regulatory, environmental, ethical, market and tax related factors may play an important role in financial innovation, diversity of Shari’a views and opinions has been instrumental in Islamic financial innovation. This has led to a huge growth in some specific areas in Islamic finance.

Three issues must be understood in this respect. The first two are well-established, while the third one is a new phenomenon. These include:

- Prohibition of interest;

- Discounted trading in debt; and

- Third party syndrome in IBF.

Prohibition of interest

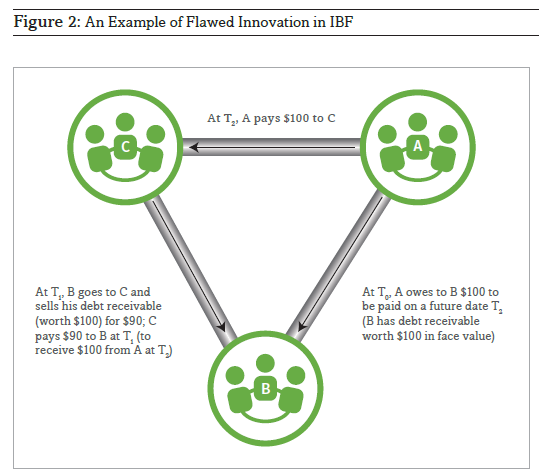

A lack of understanding of the diversity of Shari’a views in fact may lead to financial losses for the developer of Islamic financial products. Figure 2 presents an example of innovation that does not conform with Shari’a principles, as it contradicts with the generally acceptable principle of Shari’a.

In this example, a party A owes to another party B $100 at a given point in time (T0). Assuming that this is an interest-free loan, a third party C can still benefit illegitimately from this interest-free transaction is if it enters into an arrangement with party B whereby party B sells its debt receivable of $100 to party C for a discounted price of $90. This transaction happens at time T1 (whereby T1 > T0) and party B receives $90 in cash from party C. At a later agreed time, T2, party C claims $100 from party A.

There are two fundamental Shari’a issues in this transaction:

- While the leg of the transaction between parties A and B is in conformity with Shari’a, it is not so in case of the transaction between parties B and C. There also appears to be no problem in case of the third transaction (between party C and A whereby party A pays $100 to party C, as per instructions of party B).

- The above transaction is an excellent example of Third Party Syndrome, which is further discussed in a subsequent section. A well-known principle in Shari’a is that if a transaction cannot be legitimately done between two parties, it cannot be legitimised through a third

The second leg of the transaction involves discounted trading in debt.

Discounted Trading in Debt

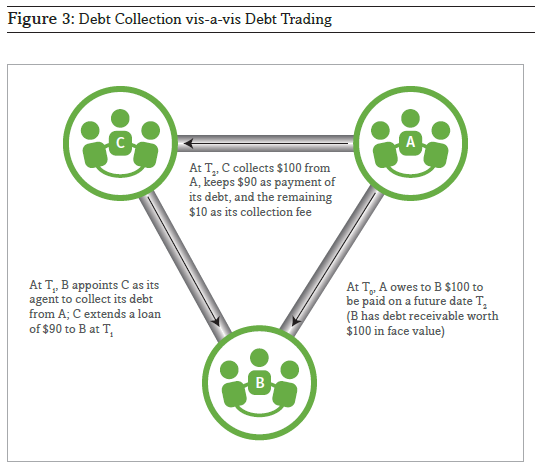

Discounted trading in debt is not acceptable in the globally acceptable Shari’a standards. However, Islamic law permits debt collection for a fee. Thus, the transaction depicted in Figure 2 can be modified with the help of introduction of debt collection, which is an agency contract (depicted in Figure 3).

Thus, at T1, if party B is in need of liquidity and it has debt receivables of $100 from party A (to be received at T2), party B can always go to a third party C to receive from it the required liquidity against an equivalent amount to be received from party B once it (party C) has collected debt on behalf of party B from party A at time T2. Effectively, party C will in this case serve two roles:

- Provide an interest-free loan of $90 to party B; and

- Act an agent of party B to collect debt from party

Caution should be exercised in this arrangement, as it combines an agency contract with an interest-free loan from the agent (party C) to the party B. A strict Shari’a requirement in this case is that the two contracts (i.e., that of an interest-free loan and of the debt collection agency) should not be combined in one contract and that they should remain independent of each other.

Independence of the two contracts requires that if one contract lapses it should not have an automatic effect on the other one. For example, if the debt collector fails to perform, party B will have to return $90 loan to C, which it had extended to B. Although in this case party B will not pay the debt collection agency fee, if the agency was based on the performance.

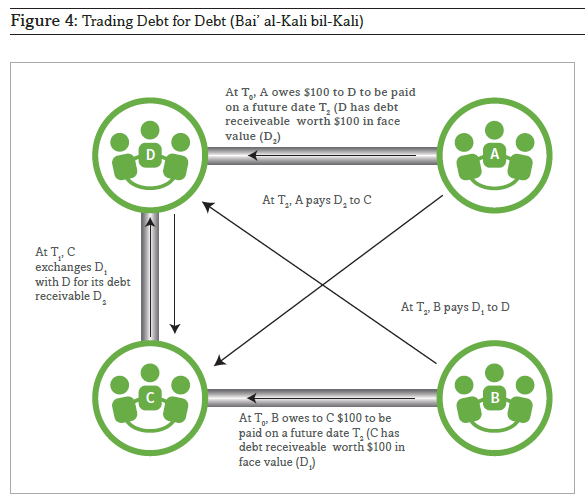

Dominant Shari’a opinion prohibits selling debt for a price other than its face value. This prohibition covers both discounts and premiums in the sale/purchase of debt. Thus an individual, corporate or any other institution (e.g., government) is not allowed to sell to a third party the debt a debtor owes to it, for a price other than the face value of the debt. Furthermore, there is a clear prohibition of selling debt for debt even if the two (deferred counter-values) are equal (see Figure 4).

There is a simple rationale behind prohibition of trading in debt. Islam does not allow re-pricing of debt even if it is between the initial creditor and debtor. This is so because pre-agreed (contractual) re-pricing of debt is likely to give rise to the pre-Islamic practice of interest, known as riba al-jahiliyya, which Islam prohibited.

Thus, if party A owes $100 to party B, it is not permitted for the two parties to agree a priori to renegotiate the debt during the term of the debt agreement.

Although a creditor enjoys discretion to offer an early payment rebate to the debtor, Shari’a does not allow formalizing this discretion in the original debt agreement between the two parties. In the case of a late payment by the debtor, classical Shari’a opinion disallows a penalty, although the contemporary Shari’a view is flexible. In the modern day practice of Islamic banking, default penalty is allowed, as long as it is used only as a deterrent to wilful non-payment or delay on part of the creditor. In practice, this means that the creditor should not benefit, directly or indirectly, from the amount of the penalty; rather it should be given away as charity.

Discretionary rebate is normally applied on early payment but may also be exercised if payments remain in accordance with the contractual schedule. It is equally permissible (rather preferred) for the debtor to pay more than he borrowed, as long as it remains discretionary on part of the debtor and there is no contractual agreement on it between the two parties.

In both the rebate and penalty cases, effectively the debt agreement is re-negotiated – potentially shortening the contract in the case of rebate (certainly in the case of early payment) and prolonging in the case of late payment or default. An important point to consider here is that the issue of rebate must remain non-contractual (and hence non-binding in nature).

Although re-pricing and limited re-negotiation of debt contracts is possible between a creditor and debtor even in Islamic finance, the mechanisms of doing so do not allow creditors to sell their debt in a meaningful way to a third party for a discounted price. For example, consider bank A that owns a murabaha asset with a face value of $100, which was created by selling a Shari’a-compliant asset to a client C on a deferred payment basis. Applying the prohibition of discounted trading in debt, Bank A can sell the murabaha asset (debt in the form of receivable) to a third party B for a price no other than $100, which must be paid on spot (by B). If A wants to sell this debt to B for a lower price, say $90, it could do so only after unilaterally forgiving (or writing off) $10 from the debt owed by C, and then selling the remaining debt for its face value of $90. Of course, this makes little sense for B who would otherwise wish to benefit from the discount. Having said that, there might be some cases wherein Parties A and B still wish to proceed with the transaction, which would be in compliance with Shari’a.

While discounted sale of debt is prohibited, Shari’a allows partial transfer of debt through agency-based debt collection. Thus, it is permissible for a creditor A to appoint a third party B as its agent to collect its debt receivable against a fixed fee and/or variable rate determined by B’s performance.

In practice, a combination of un-discounted trading in debt and the agency-based debt collection contracts can affect the economic effects of discounted trading in debt. For example, a corporate owning a debt-based portfolio worth $100 may wish to “sell” it off by selling 50% of it to a third party for its face value, i.e., $50. In addition, it appoints the same third party as its agent to collect the remaining 50% of the debt from its debtors against an agency fee of 50% of the amount collected. This combination of debt sale and debt collection gives rise to a Shari’a-compliant way of achieving the economic effect of selling $100 worth of debt, with a 25% discount.

There are two major differences between this Shari’a-compliant solution and the conventional discounted trading in debt. First, during the term of the contract between the creditor and its agent, the debt (50% of the total in this example) remains on the creditor’s balance sheet until it is paid off (i.e., it is collected by the agent). Second, the combination of (un-discounted) sale of debt and agency for debt collection is a performance-based arrangement, as the amount of “discount” very much depends on the recovery/collection of debt. If the agency fee was a fixed percentage of the amount recovered/collected, the combination model would offer a variable “discount” depending on the performance of the agent. If, for example, the agent recovers only $5 out of the total $50 to be collected then based on the agency fee of 50% of the amount collected, total “discount” received by the party B will be 4.5%. The discount increases to 8.3%, if B collects $10 instead, reaching to 25% when all the $50 debt is collected.

This combination-based debt trading has a built-in regulatory mechanism, as it allows a party to “sell” only part of its debt. An implication of this is that only a fraction of the total debt owned by a business can be

offloaded from its balance sheet. It should remain the prerogative of the industry regulator to determine what proportion of debt a business can offload from its balance sheet by determining a threshold for the sale of debt and debt collection in combination-based debt trading models.

Third Party Syndrome in IBF

There are numerous examples of what may be termed as Third Party Syndrome (TPS) in Islamic finance. The most frequently used structure of commodity murabaha may in fact be cited as an example of TPS. The commodity broker(s) in fact provide no real additional value in commodity murabaha transactions, other than serving as facilitators for structuring transactions in a Shari’a-compliant way. This has been subject to criticism since the start of application of this concept and is expected to remain an Achilles’ heel for IBF. Brokerage costs in such transactions are no more than deadweight loss, which make Islamic financial transactions more expensive than their conventional counterparts.

Therefore, there is a need to either eliminate the use of third parties in such transactions or bring a valuable economic function into Islamic financial transactions through them. The elimination of third parties can be done through the genuine use of bai’ ‘ina (instead of tawarruq), as has been the case in Malaysia. The historical use of bai’ ‘ina in Malaysia has been subject to severe criticism but the new guidelines on bai’ ‘ina ensure that the concept is used in the most genuine way in product development and structuring.

Legal Structuring

It is absolutely imperative that an Islamic financial product is structured in such a way that it not only fulfils Shari’a requirements but also is consistent with the applicable legal framework. Most of the innovation in IBF – which we have termed as process innovation – has actually come about as a result of marrying the conventional regulation and legal requirements with Shari’a assurance.

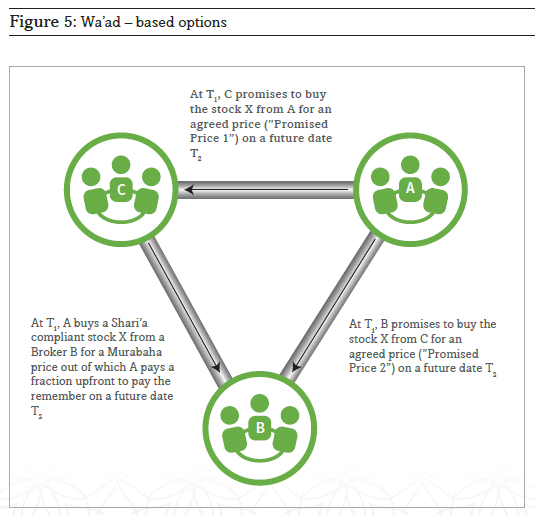

Perhaps the best example of the use of legal structuring to innovate in IBF is provided by option products based on the concept of wa’ad. As a wa’ad (promise) is binding on the promisor only when the promise calls upon the latter to perform, a wa’ad is nothing but an option. However, it is not permissible to sell a promise for a monetary value. To affect the economic effects of an option premium, a wa’ad is combined with a murabaha contract, as depicted in Figure 5.

In this structure, a party A wishes to buy a covered option on a stock in a Shari’a-compliant way. The transaction is structured by way of combining a murabaha contract with two wa’ads. Admittedly, this structure is an example of a TPS (criticized above). However, different variants of this have been used in the Islamic financial services market. Hence, we presented this as an example of innovation in IBF. The legal structuring involved in this transaction allows a purchase undertaking written as a deed poll to be considered as a wa’ad from a Shari’a viewpoint.

BOX 6: CAN IBF BE BOLD AS TO RE-INVENT ITSELF AS A COMPLETELY NEW MODEL OF FINANCIAL INTERMEDIATION?

Conventional banking model is based on deposits. Banks accept deposits and use the money thus raised to offer interest-bearing loans to individuals and businesses. This is a standard model used all over the world, and is now being used even by many microfinance institutions that emerged as non-bank entities in the 1960s onwards. In Pakistan, State Bank of Pakistan is even pushing microfinance institutions to set up microfinance banks to

ensure that such activities are brought into a tight regulatory net. Such is the power of the deposit-based banking model that even some otherwise successful non-bank institutions offering interest-free loans are tempted to set up banks to further expand their activities.

Some glaring examples of charity-based institutions are Islamic Relief Worldwide (UK), Edhi Trust (Pakistan) and some endowments like Sulaiman Bin Abdul Aziz Al Rajhi (SAAR) Foundation. There are thousands of hospitals and schools in the Muslim world, which continue to benefit from generous donations from across individual countries and from the overseas. Charitable giving is so powerful that almost all medical research bodies, including Cancer Research UK, heavily rely on charitable giving to partially fund their operations.

According to an ICM Research survey, UK Muslims give more in charity than any other faith-based group, including Jews and Christians. In 2012, amongst the surveyed respondents, Muslims gave on average $567, Jews $412, Protestants $308 and Roman Catholics $272. Contribution from the atheists was merely $177 per capita. This is a remarkable finding, which should be considered seriously for developing social enterprises in developing countries of the world, including those that comprise Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), where charity plays a tremendously important role in the absence of a state-run social security system. According to an on-going research by Edbiz Consulting, a charity-based system can be developed in Pakistan to generate Rs180 billion on a monthly basis from the top 10% population of the country. It is based on an assumption that each affluent individual in the top 10% of the population is incentivized to contribute Rs1,000 on a monthly basis. This model of charitable giving also has relevance to improving social behavior.

It is interesting to note that loan recovery rate for microfinance institutions (many of which are based on charitable giving) around the world is above 90%. It proves the point that charitable giving and support for the poor helps in curbing moral hazard problem – something of a major concern for banking institutions. Given the success of microfinance, it is worth considering to develop a donation-based, as opposed to the existing deposit-based, model of banking. The proposed model should have donation as the main product, rather than a deposit. There could be two main donations: a reversible donation and an irreversible donation. The former is a time- linked interest-free deposit that the donors should deposit with the bank for a specific time period. The latter is a simple donation that the donors should give through the bank. The money thus raised could be used for extending interest-free business loans and financing based on the principle of profit sharing. While the poorest segments in the society must be helped with interest free loans, there is some anecdotal evidence that 70% of the self employed individuals and families have some kind of preference for profit sharing based financing.

Access to Cutting Edge Technology

As IBF is embedded in the conventional financial system, structuring of Islamic financial products cannot be done in complete isolation from the modern advancements in structuring and technology. Despite four decades of history, IBF remains a sub-set of conventional banking and finance. Therefore, any product development effort can only be with reference to or in conjunction with the conventional financial markets and the products offered therein. For example, it is impossible for Islamic banks to offer transaction banking services without utilizing different technological platforms developed for this purpose in conventional banking and finance.

This approach is inevitable until a new model of IBF is developed and implemented (as proposed in this Chapter).

Deep Understanding of Market Trends and Needs

Deep understanding of market trends and needs is important for structuring innovative products for Islamic financial services industry. While in the pre-financial crisis years, a number of conventional products (e.g., collateralized debt obligations, credit default swaps and similar risk management tools) were being Islamized in an attempt to deepen Islamic financial markets, the recent financial crisis has also affected regulations in a number of jurisdictions where IBF is a significant activity. The new cautious approach to such products even in the conventional banking and finance has implications for product development in IBF. Industry observers believe that such high-end, technology intensive products will not fit well in the risk averse attitudes prevailing in Islamic financial markets.

Similarly, in certain markets some of the concepts that otherwise are acceptable may not be welcomed. For example, any tawarruq-based product will not be acceptable in countries like Pakistan, although the use of tawarruq is rampant in the Middle East and in Malaysia. Therefore, any attempts to market a tawarruq-based product is bound to fail in Pakistan.

In high-income Islamic countries like Qatar and Kuwait where poverty is not a serious issue, attempts to develop Islamic microfinance will not attract enthusiasm from the markets or from the government. However, such products are encouraged in other countries like Indonesia, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

In countries like UK where financial markets are well-developed and highly competitive, any attempts to seek Shari’a premium by way of offering Islamic financial products that happen to be more expensive than the equivalent conventional products will not succeed.

NEED FOR INNOVATION

Islamic retail banking has seen the least innovation in the last 5-10 years. Most industry observers are critical of what is happening in the Islamic retail banking market. Despite the industry rhetoric, Islamic retail banks shy away from risk sharing and/or true profit loss sharing. The use of tawarruq is rampant. In Malaysia where BNM – the central bank – is trying to push for mudaraba-based Islamic investment accounts the Islamic banks are in fact opting for wakala-based investment accounts, which is expected to result in a significant drop in the use of profit loss sharing even on the liabilities side of balance sheet of Islamic banks. Islamic home financing products remain Shari’a-compliant versions of their conventional counterparts, and have no distinct economic value proposition different from conventional home finance products.

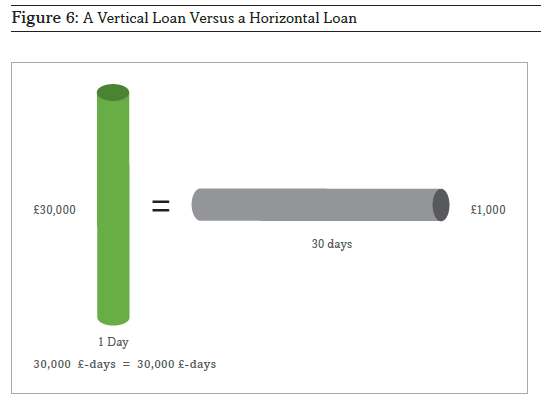

In this section, we share a possible innovation in Islamic retail banking, based on the concept of Time Multiple Counter Value Loans (TMCVLs). A TMCVL is a loan of a nominal smaller amount for a longer period (time) in exchange for a loan of nominal larger amount for a shorter period of time. For ease of understanding, a loan of a smaller amount for a longer time may be referred as a “horizontal loan” and a loan of a larger nominal amount for a shorter period may be called a “vertical loan.” The theory of TMCVLs suggests if amount- time-based points of a horizontal loan are equal to the amount-time-based points of a vertical loan, the two loans will be considered equal. Figure 6 illustrates that a vertical loan of £30,000 for one day (with a value of 30,000 £-days) is equal to a horizontal loan of £1,000 for 30 days (with the same value of 30,000 £-days).

Sheikh Mahmood Ahmed, who presented this concept as part of his PhD thesis in the 1970s, argued that a completely interest-free system of banking can be developed using this simple yet innovative idea. However, he failed to convince bankers, regulators and even Shari’a scholars of utility of this concept in the context of IBF. This failure was not necessarily due to the weakness in the concept but rather partially owing to inability of the Shari’a fraternity to appreciate it fully. The Islamic bankers of that time also did not venture into completely new ideas, as regulators of that era would not allow Islamic banks to experiment with products and services that were not covered by the regulations applicable to banks.

At present, banks and financial institutions, and as a matter of fact non-financial businesses, are applying a similar concept in structuring loyalty programmes to retain and reward their customers. Examples of such loyalty programmes include reward programmes by retailers, air miles cards by airlines and cash back facilities on credit cards etc. These loyalty programmes are indeed part of customer engagement strategies of these businesses to acquire, retain and manage their customers effectively to sustain and further develop their businesses.

Feasibility of the Product

Assume that an Islamic bank offers a fixed deposit product to its customers requiring them to deposit $10,000 for 10 years. The product attracts 1,000 customers depositing $10 million in total. The participating customers are eligible to apply for shorter term interest free loans of dollar-day value of $36.5 million from the bank. For example, an individual depositor may want to get a loan of $100,000 for one year (with a dollar-day value of 36,500,000), or a loan of $200,000 for six months, or $400,000 for 45 days.

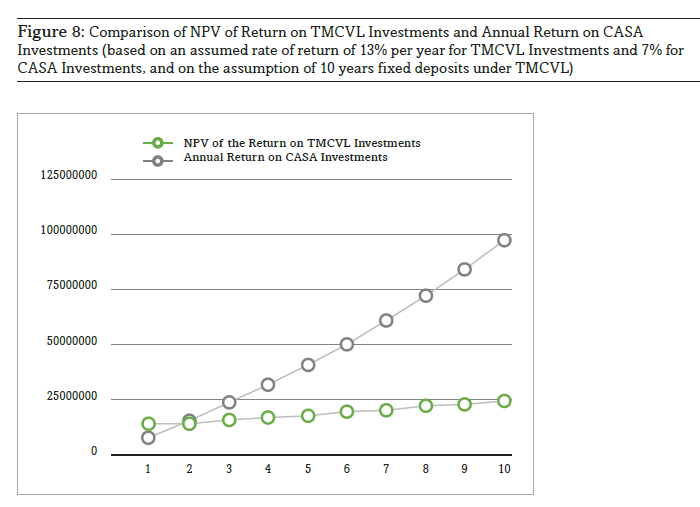

If all the 1,000 participating depositors decide to apply for $100,000 for one year, the bank will require $100 million to meet this demand. This amount can be taken out of CASA (current and saving accounts) pool or, less preferably, from fixed deposit pool. Figure 7 is based on the assumption that an Islamic bank has $1 billion in CASA and another $4 billion in fixed deposits. If the bank has to extend $100 million worth of interest-free loans pursuant to its obligations against TMCVL deposits, it can take this amount from CASA pool. The bank would loose an opportunity to extend this amount to earn a return of 7% on its financing out of CASA pool

($7 million for 12 months). However, this loss can be more than compensated by the long-term financing of $10 million TMCVL deposits. As investments from CASA pool are of short term duration, they carry a lower return as compared to long-term investments. The Figure assumes that CASA investments yield an annual rate of return on 7%, the investments of the fixed deposit pool a rate of return of 10%, and the investments of the TMCVL deposits a return of 13% per annum.

“Figure 9 compares NPV of return on TMCVL investments and annual return on CASA investments over a period of 25 years. It clearly indicates that the bank will have a period of almost 6 years in which it will be required to raise additional $10 million deposits under TMCVL to maintain its profitability. Of course, a bank that succeeds in raising $10 million deposits under TMCVL will benefit from higher income.”

Given this, the bank in fact swaps $100 million of financing to the TMCVL customers for one year with a $10 million investment form the TMCVL deposits for a period of 10 years. The loss of income on $100 million per annum interest-free loans is $7 million, while the gains on a 10-year investment of $10 million is $23,945,674 (with a net present value (NPV) of $13,024,360 at the end of the year 1). Clearly, this is far superior to investing $100 million from CASA pool in short-term instruments. In fact, in many cases, it will be more lucrative than returns on the medium-term investments from fixed deposits pool.

This clearly indicates that TMCVL product is not only viable for Islamic banks but in fact is more profitable. Its additional benefits include customer loyalty, stability of balance sheet and sustainability of business. Figure 8 compares the effective rates of return on TMCVL investments and CASA investments. It is important to clarify that TMCVL investments bring additional return to the bank to the point when annual returns on CASA investments are lower than the NPV of the return on TMCVL investments. In the current example, if the bank continues to attract $10 million worth of deposits on an annual basis, it will generate additional income of $6,024,360 on an annual basis. Lengthening the tenure of deposits will bring further benefits to the bank.

Shari’a Issues

Needless to say that any product based on TMCVL must carefully be structured to ensure strict conformity with Shari’a principles governing qard hasan or interest-free loans. TMCVL is essentially based on two interest-free loans – an issue that requires considerably cautious approach from a Shari’a viewpoint, as it can give rise to the prohibited riba if handled negligently.

It is an absolute requirement that the two interest-free loans should be completely independent of each other and in no way should be deemed conditional upon each other. If the offer of $100,000 interest-free loan to the customers for one year is conditional upon the customer depositing an interest-free loan of $10,000 for 10 years, it will be deemed as an illegitimate benefit (riba) accruing to the bank. The independence of the two interest-free loans can be ensured by including the following clauses in the product terms and conditions:

- It must clearly be stated that the TMCVL deposit (i.e., the horizontal loan) by the customer is in no way a condition of the bank extending an interest-free loan of larger amount and a shorter period (i.e., the vertical loan) to the customer;

- It should also be mentioned in the product terms and conditions that if the customer does default on its loan obligations, the bank will not automatically default on its obligations towards the customer (i.e., it will still have to pay the deposited amount under TMCVL to the customer irrespective of weather the customer defaults or not);

Condition 1 implies that the bank cannot offer this product by way of requiring a horizontal loan, and that it cannot bundle the two arrangements (horizontal deposit and vertical loan) at the time of offering the product. However, the bank can advertise the fact that those customers participating in the horizontal deposit programme will be considered for a vertical loan as and when they decide to call upon the facility. This facility should not be considered as an obligation on the bank but rather a discretion on part of the management.

Given this non-bindingness, the bank will have to develop a culture of trust ensuring long-term relationships between the customers and the management. This will also imply that the bank will have to develop a culture of loyalty within its own organization to ensure that its key employees remain with it for sufficiently long periods. Trust and loyalty of the employees can be won by way of distributing organizational benefits equitably amongst all the stakeholders.

Careful examination of a product like TMCVL reveals that it is not just introduction of a product in the menu of services offered by the bank, but rather it is about changing the overall culture, management style and the overall objectives of the business. There is no doubt that the real benefits will start accruing to the bank in the long-run, and there will be certain immediate cost implications for which the bank should be ready to dedicate some additional resources.

Other Applications

Application of TMCVL is not limited to receiving long-term deposits and offering short-term financing. The concept can equally be applied to developing long-term financing products like pension programmes, savings for children, interest-free overdrafts, and home purchase plans. In fact, it is not only possible but absolutely viable to develop a new model of banking based on this “quid-pro-quo” model of TMCVL.

Central to the idea is to create an environment whereby banks and their customers are engaged cooperatively. If the customers know that the bank is not charging them interest, then they will be willing to put their additional funds with the bank without expecting any return. If combined with charities and donations (see Box 6), this can emerge as a very powerful model of banking – a true alternative to conventional interest-based banking system.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

This chapter focused on innovations in IBF to provide some food for thought to those who are involved in product development and structuring in the institutions offering Islamic financial services. The main argument here is that there is a dire need for developing a new financial system independent of the existing practices of banking and finance. This will certainly involve significant innovation in the field of financial services, and hence is expected to be a gradual process. There is therefore a need to make deliberate efforts to move out of the current practices of innovation (which is primarily an example of process innovation) into product innovation, to eventually give rise to what may then be termed as systemic innovation in IBF. This will certainly take some time, and it is expected that a new financial model will start taking shape by the end of the next decade if immediate steps are taken to move into that direction.

IBF has made significant progress in the last few decades, particularly in the last 15 years. The recent financial crisis has certainly opened a window of opportunity for IBF to develop an alternative model of banking and finance. This alternative should replace the current financial system that have been viewed with a lot of suspicion by the users of financial services. The financial regulators have also opened up their minds to explore better ways of financial intermediation. The question arises: Is Islamic banking and finance ready to accept the challenge?

BOX 7: NATIONAL BONDS – A STORY OF INNOVATION

Established in 2006, National Bonds Corporation (National Bonds), licensed and regulated by the UAE Central Bank, is a Shari’a-compliant savings scheme that provides UAE nationals, UAE residents and non-residents with credible and safe options in savings and investment. This was the most innovative product of its kind, when launched and since then has inspired a new breed of prize-linked Islamic investment products.

National Bonds is a private joint stock shareholding company, with a paid-up capital of AED150 million.

It is 100% owned by the Investment Corporation of Dubai, the investment arm of the government of Dubai.

To its credit, National Bonds has positioned itself as a leader in the savings and investments sector acquiring more than 800,000 clients to date from over 200 nationalities.

As part of its continued commitment towards inculcating a savings culture, the National Bonds Savings Index initiative was launched in 2011 with the aim of providing a comprehensive study on popular saving instruments, as well as the barriers to saving and people’s spending habits in the UAE and the wider GCC region.

The findings of the study helped National Bonds design tailored solutions for targeted groups. This includes the:

Î Employee Savings Programme provides government and private sector employees with an opportunity to save through direct monthly deductions from the employee’s salary. It also entitles employees to all benefits and rewards offered by National Bonds. The programme provides an easy solution to empower employees through offering personal finance management assistance. The service plays a major role in facilitating and enabling employees to start their journey towards achieving financial health and peace of mind.

Î Financial Well-Being Program is a unique financial literacy programme, offered to public sector organizations and corporate establishments throughout the UAE as part of National Bonds’s staff training and welfare initiative. National Bonds’s complimentary seminars help educate salaried professionals about the importance of developing a sustained savings habit to ensure a secure financial future for themselves and their families.

BOX 8: INNOVATIONS IN STRUCTURING OF ISLAMIC FINANCIAL PRODUCTS IN THE MENA REGION

The Gulf-Cooperation Council (GCC) countries have been at the forefront of remarkable economic growth in recent years. As most GCC countries have Islam as their official religion, this has created an ideal environment for Shari’a-compliant financial services products to flourish and grow. The system of laws in each GCC country generally recognizes certain basic Shari’a contracts in their commercial legislation, such as mudaraba and musharaka.

The body of commercial laws, whilst recognizing certain Shari’a principles, also incorporates elements borrowed from Western commercial laws, in particular the French Napoleonic code. This marriage of different sources of legislation creates an exciting and dynamic environment for growth and innovation in financial services products.

Several of the MENA countries contain financial free zones. At present the State of Qatar has the Qatar Financial Centre (QFC) and the Emirate of Dubai in the United Arab Emirates has the Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC). Abu Dhabi, the capital of the United Arab Emirates, has also announced the creation of a new financial free zone, called the Abu Dhabi Global Market (ADGM) and a new set of laws for this free zone is presently being drafted. It is anticipated that this center will become operational during 2015.

Financial free zones offer a completely distinct legal environment for regulated financial services activities, outside of the country within which they are situated, and offer one hundred percent foreign shareholding. As such they may be seen as offering more scope for innovation in financial services, since their legislation is bespoke. That said, their legal systems are generally based on common law systems and their target market is not primarily

Islamic, rather it is to invite international investors into their country, which is why the one hundred percent foreign shareholding is an important element in their legal composition. Having said that, development of such free zones helps in generating interest in IBF amongst the businesses domiciling therein.

However, MENA domestic markets offer more fertile ground for product development in the Islamic retail market than the free zones. Institutions incorporated within free zones are not generally permitted to operate outside of those free zones. There are presently no retail banks or insurers offering products to the domestic market from within a financial free zone, other than where they have a license to operate outside of that free zone within that sector. Free zone entities within the financial services sector have to comply with general financial services licensing outside of the financial free zone in order to provide services outside of that free zone. This operates as a practical restriction on anything other than high value business and financial transactions and reinsurance activity taking place within the free zones, although they do offer a fertile ground for developing new structures. This Box examines some of the innovations coming from the non-financial free zones in more detail.

To date, the majority of the Shari’a-compliant organizations and Shari’a-compliant products offered within the region, whether by conventional organizations operating an Islamic window or products delivered by institutions operating on an entirely Shari’a-compliant basis, have been born out of a marriage between legislation designed to regulate conventional financial products and legislation (of varying degrees of sophistication) for Islamic banking and specific Shari’a-compliant products. The backdrop of a conventional financial services regulatory framework, with specific legislation for Shari’a-compliant products, means that organizations and products are first structured to be compatible with the laws regulating the financial services industry and second Shari’a-compliant. This creates issues in structuring products which are both legal and compatible with the expectations of the consumers, and with the principles of the Shari’a. The initial years saw a flurry of innovative and new products as the industry sought to shape products to meet demand. Every year saw a completely new set of structures. Recent years have seen a pattern of consolidation and application of tried and tested structures to new asset classes, markets and consumers. In a sense this is a sign of the growing of age of the market.

What is clear is that the global Islamic market demands innovation and new products, as well as consolidation of existing products, in order for the market to continue to grow. Interestingly, the last twelve months have seen a pattern of refinement and consolidation of existing structures, with new players entering into the market, rather than wholly new structures. It has been a creative period, not from the perspective of new structures, but from the manner in which existing structures have been employed.

The two main areas which have dominated headlines in the MENA Islamic financial services sector during 2014 are Islamic syndicated financings and sukuk. In the background there has been a steady growth in the rise of Shari’a-compliant investment funds. The resurgent confidence in the GCC markets coupled with regional government investment into large infrastructure projects in order to meet the projected needs of a relatively young population has been a key factor in this growth.

Another area which was a highlight of 2014 was that MENA banks have built out into the international markets. During 2014, banks such as National Bank of Abu Dhabi and Emirates NBD were taking key roles on international issuances. This should be an ongoing trend as countries like Hong Kong, Turkey and other emerging players in Africa and central Asia look to MENA banks for their expertise in Islamic finance. While in 2014 global players continued to dominate the sukuk issuance (with HSBC and JPMorgan Chase emerging as the top two underwriters in the MENA region), the local players like National Bank of Abu Dhabi (NBAD) also emerged as important contributors. NBAD finished in third place in the table for its role in sukuk issuances in 2014, which is an impressive achievement by a local bank.

The appetite to enter into financing arrangements on a Shari’a-compliant, rather than a conventional basis, is based largely on the fact that, with the depth of experience in the Islamic banking sector, the pricing and documentation no longer creates significant risks or complications for parties in considering whether to enter into conventional or Islamic financing. In addition, the rebirth of the large construction projects, based on growing investors’ confidence in the market, has created a need for creative financing solutions to tap into the large pool of Islamic investors. Given the scale of the order books of the governments of the GCC states, most notably the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, it seems likely that this trend will continue.

During 2014, GCC markets maintained their place in the global sukuk market, accounting for approximately one quarter of the global value of the total new sukuk issuances in 2014. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are the regional market leaders for sukuk issuances, representing the bulk of this funding. The Emirate of Dubai in the United Arab Emirates continues to press to be the global capital for Islamic finance, and by extension, innovation in Islamic finance. The listing of the US$1 billion sukuk by the government of Hong Kong on Nasdaq Dubai during December 2014, lends additional credibility to this ambition. This represents the first US dollar-denominated sukuk issued by an AAA rated government listed on Nasdaq Dubai. This is a huge achievement for the Emirate. Dubai is one of the market leaders in sukuk issuance globally, standing alongside London and Kuala Lumpur. It seems likely that Dubai will continue to lead the way in Islamic capital markets in the coming years.

By contrast the government of the Sultanate of Oman has not yet seen any sukuk issuance, although the Omani government has announced that its inaugural sovereign sukuk of US$519.5 million will be issued during 2015. This first of its kind of sukuk issuance was originally anticipated to happen during 2013, which saw the inaugural sukuk from Omani corporates. Of particular note is that the Central Bank of Oman (CBO) has set up a Shari’a board of its own, setting it apart from the other GCC states (apart from the Kingdom of Bahrain) in forming a centralized Shari’a supervisory board. Other countries choose to leave this role for the private sector. The Sultanate of Oman has only recently introduced legislation to allow for Islamic banking, with CBO issuing licenses to fully-fledged Islamic banks and windows. Bank of Muscat, Oman’s largest bank by assets, received its license to offer Shari’a-compliant products and services in early 2013. Oman’s Capital Market Authority completed the drafting of bylaw that regularizes the issuance of sukuk and the proposed amendments to the Capital.

Market Law which allowed for the issuance of sukuk, opening the way for Tilal Development Company (TDC) to put in place an ijarah sukuk worth OMR50 million (US$130 million). This was an exciting time for development in Islamic finance in the Sultanate of Oman.

2014 was the year which marked the rise of alternative regional trading platforms, to support the wide usage of the commodity murabaha within the region. The Islamic financial market requires commodities in significant volume and value in order to feed the flow of the murabaha transactions, since these are pegged to Shari’a-compliant commodities. Historically most transactions have been done through the London Metals Exchange (LME) in the City of London. The Dubai Multi Commodities Centre (DMCC), a free zone within the Emirate of Dubai, operating in the Jumeirah Lakes Towers area, has its DMCC Trade flow platform.

This offers up Shari’a-compliant warehoused commodities for use in murabaha transactions. This exciting innovation meets two needs: the need of the market for products to be used in commodity murabahas and also uses commodities which otherwise sit unutilized within regional warehouses. The decision by DMCC to create a trading platform, with the ability for title to be registered in the form of negotiable electronic warrants, meant that regional banks are now able to even view the underlying commodities, if required. The use of documents of title for commodities in the form of warehouse receipts, allows DMCC Trade flow participants to transfer the ownership of assets to another party without the movement of the goods, and to use goods as underlying collateral in order to secure financing for their future operations.

However, DMCC are not alone in trying to meet the need for commodities. Nasdaq Dubai, which lists approximately $21bn of sukuk has been looking to expand its Islamic trading platform as part of the drive to make Dubai the world capital for the

Shari’a-compliant economy. Launched in April 2014, the Nasdaq Dubai Murabaha Platform comprises assets that regional Islamic financial institutions can use to back transactions for their customers.

Nasdaq Dubai has been looking to increase the range of securities it offers and it will be interesting to see how well the regional markets respond to the availability of local options. Emirates Islamic Bank was the first lender to join the Nasdaq Dubai Murabaha Platform in 2014. It is anticipated that global Islamic assets will rise into many trillions in the coming years so the competition to be the global Islamic finance capital is heating up.

The rise in these trading platforms is alongside a rise in products offering the ability to execute.

Shari’a-compliant hedging transactions. One such product launched in 2014 by Qatar Islamic Bank was a product underpinned by a wa’ad and a commodity trading structure, requiring Qatar Islamic Bank and a trading counter party to jointly sign master terms and conditions. These are combined with two master undertakings where the counter parties undertook to ‘purchase’ certain identified commodities from each other under opposed conditions. An agency agreement appointed Qatar Islamic Bank as agent to buy or sell commodities on behalf of the trading counter party depending on which undertaking is exercised. Such products are testament to the increased sophistication of the Islamic finance market within MENA. Admittedly, this is not a new structure, as this was developed by Deutsche Bank in 2006, as a path breaking product. However, its application in the MENA region by local players in certainly a progressive trend.

The growing use of sukuk as a means for MENA banks to raise Tier 1 capital in order to meet Basel III capital adequacy requirements has been a trend during 2014. June saw the Abu Dhabi government owned Al Hilal Bank issue US$500 million Tier 1 sukuk certificates which was well-received within the market, this follows issues of sukuk by other major banks such as Abu Dhabi Islamic Bank (ADIB) in previous years. There is now a general trend emerging for banks to issue Tier 1 instruments on a both conventional and Shari’a-compliant basis in order to support their ongoing growth and development. The capital adequacy imposed by Basel III means that banks require further Tier 1 capital in order to grow. Given that these banks have a key role to play in supporting financing needs of a growing population, and the growth of MENA corporates, this is set to be an ongoing trend.

Other strong issues in the UAE during 2014 included the issue of the inaugural Emaar Malls Group Sukuk, which was eagerly anticipated in the market and was successfully priced at US$750 million (Dh2.75 billion) with a ten year term. This was well received in the global markets with the order book reportedly closing at approximately US $5.4 billion, representing an oversubscription of more than 7 times, with approximately forty percent of the investors coming from Europe and thirty percent from Asia. This demonstrates the global reach of MENA corporates and the excellent growth which the region continues to experience.

With the growing maturity of the Islamic finance market, the transaction size is growing. One of the largest regional sukuk offerings was Saudi Electricity Company (SEC), being the GCC’s largest utility company, issuing a record-breaking US$2.5bn sukuk, which was the largest ever Rule

144A sukuk offering. There has been an increase in the number of regional sukuk that are structured so that they can be marketed to US and other international investors. This sukuk issue consisted of two separate series of sukuk certificates, priced differently: US$1.5 billion 10-year series and a $1 billion 30-year series, with profit payments payable on a semi-annual basis. There is a large potential for sukuk to be used to finance large corporates and infrastructure within the Kingdom Saudi Arabia and this seems only set to increase in the coming years, given the large order book for infrastructure development projects which the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has announced.

Another remarkable area of growth has been Islamic financing for aircrafts. Regional carriers are now expanding into debt capital markets. Following Emirates Airline’s US$1 billion sukuk in March 2013, FlyDubai (the trading name of Dubai Aviation Corp) issued a benchmark dollar sukuk of US$500 million in November 2014, The Islamic structure for aviation assets is now tried and tested. It is expected that this pattern will continue as MENA airlines expand their global reach and their financing requirement grow apace with their global footprint. It will be interesting to see if Saudi Arabian Airlines also uses a sukuk structure. It has plans to double its fleet by 2020. According to Boeing, Middle Eastern airlines will need 2,600 new aircrafts over the next 20 years, and industry analysts believe that sukuk will be part of the financing mix.

The other major area of innovation during 2014 was the continued rise of Islamic private equity and the ongoing growth of the Islamic investment fund industry. As with sukuk, the asset classes targeted by Shari’a-compliant investment funds are becoming increasingly sophisticated, allowing for investments into appropriate industries and asset classes. Traditionally dominated by real estate, 2014 saw the rise in interest in creating a global halal economy, with several cities competing for the crown of the global Islamic economic capital, most notably London, Dubai and Kuala Lumpur with Doha and Bahrain also staking their claim to this title. This interest in creating a wider Islamic market is opening up new potential avenues for investors, such as hospitality, textiles, media, food and lifestyle products all being offered on a halal basis. The growth of the Islamic economy creates new opportunities for investors to consider, noting that the acquisition of income-generating assets and companies has become more likely as the underlying structures have become more well-understood by investors and their application better tested by practitioners. This offers new avenues for future innovation. Rather than taking conventional investment structures and through the use of basic Shari’a-compliant instruments, creating a Shari’a-compliant wrapper, the potential is there for a truly Islamic financial market. An entire alternative economic system is potentially available where the end product and the economics surrounding a transaction are all truly Shari’a-compliant, including the intention, rather than the manner in which it was structured. This is a truly remarkable prospect.

The demand for growth in SME funding within the MENA region is also a potential driver for future growth and innovation in Islamic finance. This year saw the launch of Beehive in the UAE, an online marketplace for peer-to-peer lending. Whilst this initial offering is not Shari’a-compliant, the principle of peer-to-peer lending is an ideal basis for structuring a Shari’a-compliant platform and it seems a matter of time before this platform is created. Such a mutual model is highly compatible with Shari’a principles, as it encourages a spirit of cooperation and also sharing of risk and reward and may be created on the basis of a musharaka or mudaraba. Encouraging the use of a co-operative model in financing by creating legislation for Shari’a-compliant credit unions would also create more enterprise and opportunities for SMEs within the region. This would be a further driver for economic growth within the region.

To many in the Islamic finance market, 2014 was not the year for ground-breaking first of their kind deals, but rather the year the industry came of age, as the deal size increased and international recognition for MENA achievements within the industry was forthcoming. This is the natural progression for the Islamic finance industry within MENA, and there have been many notable and exciting transactions. What is more exciting is the increasing international reach of MENA governments, corporates and financial institutions. This should be seen as the true innovation in 2014. The financial world is now focused on the MENA as a place in which Islamic finance will continue to grow.