INTRODUCTION

Although Islamic Development Bank (IDB) and Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB) published a 10-year master plan for the Islamic financial services industry in 2005, there has nevertheless been no proper follow-up since then. The industry has now attained a size of nearly US$2 trillion (see Chapter 1) and, as the Table 1 in Chapter 1 suggests that, by 2020 global Islamic banking and finance will be worth US$5.3 trillion. This seems like a far-fetched idea, as there does not exist a collective strategy for growth of the industry and its competition with the conventional banking and finance. The industry has grown to this size without any proper and deliberate strategy on a global level to strengthen and consolidate it. As mentioned in Chapter 1, the catch-up period between the actual and potential size of the industry is increasing with every passing year, and without a collective global strategy for growth, reducing the size of the gap will be a daunting challenge.

Furthermore, after an initial phase of rapid growth in which Islamic banks outpaced conventional banks in most markets, outgrowth is waning in key geographic regions, including Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates in the Middle East and Malaysia in the Far East. It is expected that the growth advantage of IBF will lead to an environment wherein Islamic and conventional markets will experience similar growth patterns. Given the shortage of data, it is hard to estimate when this is going to happen, but some early warning indicators have already started emerging.

GIFR’s own analysis of 2020650 (i.e., there will be at least six countries in the world with at least 50 percent market share of IBF by the year 2020), which was published in the 2013 report, does not seem to be working for at least one country – Malaysia. With the IBF’s current market share of 23%, it seems unlikely that the country will have its IBF sector as large as its conventional counterpart, unless the government gives further push to the growth of IBF. The government has already taken some concrete steps to strengthen IBF in Malaysia. The enactment of Islamic Financial Services Act (IFSA) 2013 was a major milestone in this respect. But this is not going to lead to any significant increase in the size and share of IBF in the country. On the contrary, it may have a decelerating effect, as incumbent IBFIs and the new ones would take some time to adjust themselves to some of the new more stringent regulatory requirements.

Collective Strategy for Growth and Competition

However, there are some other countries where growth of IBF has seen resurgence. Pakistan, for example, has shown a lot of commitment to IBF after the change in government in 2013. In addition to Karachi, featuring in this report as the seventh most important CoE in the world (see Chapter 16), other cities like Lahore and Islamabad have started becoming active and visible in the IBF market.

There is no doubt that the real push for growth and competition must come from the individual governments in the countries where IBF is significant in size and proportion, there is still a case for developing a collective strategy for growth and competition within the Islamic financial services industry and with its conventional counterpart. The national markets must be strengthened in favour of IBF, with a strong coordination function on a global level. A collective global strategy is also required to determine a definite future path for further developments. A natural candidate to play such a role is IDB, and one should expect that in the face of the vacuum being observed, a body like IDB will initiate something in this respect, as it did in the form of the aforementioned 10-year master plan.

There are a number of Islamic financial conglomerates (e.g., DMI Trust, Dalla Albaraka Group, DIB, KFH, QIB and ADIB etc.), which have expanded into multiple jurisdiction. These groups must start talking to each other to devise a collective strategy for capturing further grounds from the conventional financial institutions. There is a case for the likes of CIBAFI to play a more active role here. As an associated body of the OIC, it must beef up its efforts to put the issue of competitiveness and growth of the Islamic financial services industry on the OIC agenda.

GLOBAL ISLAMIC FINANCIAL INFRASTRUCTURE

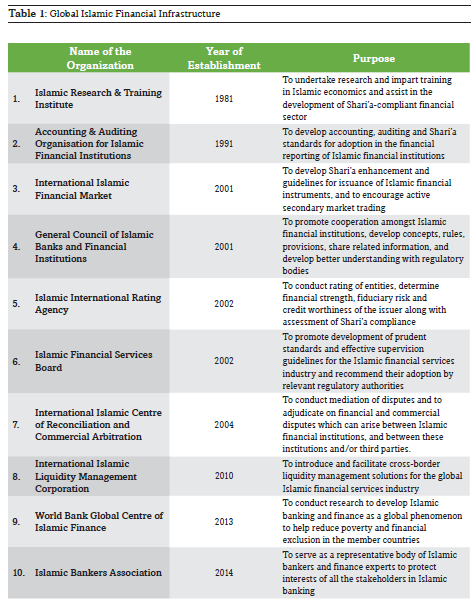

Table 1 lists ten important institutions that form the global Islamic financial infrastructure. In addition to the listed institutions, a number of other industry-building projects were set up during the last four decades. Some of them proved to be not as successful as the others were. For example, Liquidity Management Centre (LMC) was set up in Bahrain in 2002 to facilitate development of inter-bank money market and provide short-term investment opportunities to IBFIs. However, LMC has now ended up being merely a sukuk advisor/arranger/ administrator. Similarly, Islamic International Rating Agency (IIRA) has yet to achieve its stated objectives.

While on an individual level these institutions are serving the purpose of their existence, there is no proper coordination among them to take the industry to the next level. In the absence of this global coordination and the vacuum in global leadership of the industry, it is not surprising to see that some consultancy firms have started delineating policy agendas for IBF. For example, a Middle East-based consultancy firm took it upon itself to change the nomenclature of Islamic banking to participation banking in one of its publications. Obviously, this was influenced by the use of the term in Turkey where the word participation was used to circumvent political aversion to any thing Islamic or called Islamic.

Similarly, in the absence of a collective view taken on the role of Shari’a scholars in IBF, criticisms of all sorts have in the recent past surfaced exaggerating the conflict of interest the Shari’a scholars face when advising on Islamic financial transactions.

The best example of the adverse implications of failure to adopt a global strategy for growth and competition for IBF is that of the missed opportunity in the wake of the recent global financial crisis. While the whole world started taking keen interest in IBF to evaluate its potential as an alternative to the Western model of banking and finance, there was no one (individual, institution or government) in the entire Muslim world, which could address the challenge effectively. There were all kind of hallow slogans but no real and substantial attempt to present IBF as a viable alternative to conventional financial system. Consequently, a huge opportunity was missed, which could have given an unparalleled boost to the growth of IBF in the world.

STRATEGY FOR GROWTH AND COMPETITION

There is some anecdotal evidence emerging that, on a macro level, growth in IBF starts decelerating after the IBF industry attains a share of 20% of the financial sector of a country. On a micro level, however, it is an uphill task for the Islamic banking teams at conventional banks to grow their business to the 20% of the total business of the banks. The top management of conventional banks is concerned with the cannibalization of their conventional business by Islamic banking, without necessarily bringing additional value. Once Islamic banking becomes a significant activity within a conventional bank, its further growth within the bank becomes easier.

“The best example of the adverse implications of failure to adopt a global strategy for growth and competition for IBF is that of the missed opportunity in the wake of the recent global financial crisis. While the whole world started taking keen interest in IBF to evaluate its potential as an alternative to the Western model of banking and finance, there was no one (individual, institution or government) in the entire Muslim world, which could address the challenge effectively. There were all kind of hallow slogans but no real and substantial attempt to present IBF as a viable alternative to conventional financial system. Consequently, a huge opportunity was missed, which could have given an unparalleled boost to the growth of IBF in the world.”

On a global level and in particular national contexts, growth in IBF can come with both greenfield and brownfield expansion. Greenfield expansion can be attained by developing new markets and products, and through targeting the financially excluded segments in the countries in the Muslim world. On an institutional level, growth of Islamic banking is primarily through cannibalization, which, as stated above, is resisted by the top management at early stages of development of Islamic banking.

Brownfield growth can be achieved by devising a comprehensive strategy for competition with the conventional banks, insurance companies and other financial institutions. Without such a strategy, the conventional banking bosses within the large groups with Islamic banking operations will always restrict growth of Islamic banking business, owing to the fear of cannibalization. A number of heads of IBF within conventional financial institutions share this frustration. The limits to growth of IBF within conventional financial institutions is real, and it requires special attention by the global and national industry-representative bodies and institutions.

On a macro-level, this implies creating a level-playing field for Islamic financial institutions to compete within the mainstream financial sector. This essentially implies recognition and implementation of a dual banking system for introduction of IBF in countries where it has previously not existed. There is a need to develop comprehensive guidelines for developing and implementing a dual banking system on a country level, with a focus on its objectives, required legislative changes, regulatory framework, taxation regime, and a competition policy. In case of Muslim countries, the dual banking system should also include a targeted threshold percentage of IBF in the financial sector by a chosen date.

The following 10 points must be considered for adoption in a global strategy for growth and competitiveness of IBF:

1 Increase in Size of the IBFIs

Despite phenomenal growth in IBF in at least some of the countries, nowhere in the world, an Islamic bank can boast to be the market leader. Even in Saudi Arabia, where Al Rajhi Bank is a major player in the banking sector, it falls behind National Commercial Bank (NCB), which is the largest bank in the GCC region.

One obvious way of increasing size is to beef up the capital base of Islamic banks. There have for long been attempts to create a mega Islamic bank – most recently by the Malaysian and Indonesian governments but before that by the likes of Sheikh Saleh Kameil – but these attempts have yet to come to fruition.

To grow organically, IBFIs must retain sufficient profits to enable them to purchase new assets, including new technology. Many shareholders, especially the smaller ones, may find it unattractive at least in the short-run. However, such a policy is in the best interest of the business and its owners, as over time the total value of individual IFBIs will rise, providing them collateral to enable them to raise more funds both in equity and debt.

2 Brand Development

Unlike some other mega brands that a few non-financial firms (e.g., Emirate Airlines) and banking groups (e.g., QNB) have created in the recent past, IBF has yet to succeed in this respect. Although the likes of Kuwait Finance House (KFH), Dubai Islamic Bank (DIB), and Albaraka are well-known brands in IBF but their recognition is limited to the Islamic financial markets.

One of the most common strategies for internal growth is to build the firm’s brand, which provides the firm with many advantages. Once a brand is established, less advertising is required to launch new products.

Internal growth often provides a low-risk alternative to integration, although the results are often slow to arrive.

Brand development and identity are slightly two different areas. Changing name of an Islamic bank (e.g., from Noor Islamic Bank to Noor Bank) and changing its logo (like the recent change in the logo of Dubai Islamic Bank) are two different propositions. While Noor Bank decided to change its Islamic identity in favor of a more mainstream name, Dubai Islamic Bank’s recent move has been to modernize its logo, with slight modifications to its original logo.

At this stage when brand strengthening is required, some consultancy firms are advising Islamic banks and financial institutions to change their identity to look like mainstream financial institutions. The desire to make IBFIs mainstream is so strong that, as stated above, one particular consultancy firm has started calling Islamic

3 Quantification of Demand

A first step towards developing IBF is to identify and quantify demand for Islamic financial services in the targeted markets. Apart from Pakistan, no other country in the world has taken a systematic approach to determining the demand for Islamic banking. Without having an objective view on the demand and its nature, developing a strategy for growth and competition will not be effective.

Authentic market research is absolutely important to devise a comprehensive and dynamic model of Islamic banking system. In case of Pakistan, for example, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) commissioned a Knowledge, Attitude and Practices (KAP) study to quantify demand for Islamic banking in the country.

“Empirical evidence on the relevance of DCR in Pakistani Islamic banking suggests that 62% of the respondents would not withdraw money from an Islamic bank, if it announces a rate of profit less than the market rate of return.”

The study was funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) and undertaken by Edbiz Consulting.

For keen readers who would like to learn more about KAP Report, an online version is available on http:// edbizconsulting.com/publications/KAPStudy.pdf. The concepts like Shari’a premium and displaced commercial risk (DCR) have direct implications for growth and competition. However, these concepts were introduced to Islamic banking without any objective justification. It seems as if the Islamic bankers (trained in the conventional tradition) wanted to practice Islamic banking as close to conventional banking as possible. To do so, they highlighted the unique risks like DCR and suggested mechanisms like profit equalization reserve (PER) and investment risk reserve (IRR).

There is a need to test hypotheses around applicability of such concepts in the context of IBF, with the help of real data rather than opting for subjective analyses. For example, empirical evidence on the relevance of DCR in Pakistani Islamic banking suggests that 62% of the respondents would not withdraw money from an Islamic bank, if it announces a rate of profit less than the market rate of return. Furthermore, DCR was not found to be contributing significantly to the construction of demand index for Islamic banking. Empirical studies like KAP can help understand demand for Islamic banking and the factors affecting it.

4. Development of New Markets

The so-called Arab Spring brought optimism in favor of IBF in a number of countries, including but not limited to Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Tunis, Algeria, Syria and Oman, but it has taken a lot longer to introduce IBF in these countries than what industry observers expected. While in Oman, the introduction of IBF has been smooth; in other countries the political turmoil has not been entirely helpful. Similarly, after some initial enthusiasm in some African countries like Nigeria and Kenya, the growth has been rather slow. Furthermore, the central Asian Muslim countries have also been slow in introducing or adopting IBF. Kazakhstan has been an exception but even there the follow up has been lukewarm.

Interestingly, apart from the North African countries, other African countries that have shown interest in IBF are the ones with Muslim minorities, e.g., South Africa, Nigeria and Kenya. The Muslim-majority African countries have not so far taken a lead role in developing IBF as part of a national strategy. One business group in Somalia has in the recent past started looking into setting up an Islamic bank. Given the ongoing civil war in the country, even this may not lead to optimism with reference to IBF in the African continent.

Despite this grim picture of macroeconomic conditions and socio-political environments, IBF has a potential to grow in these countries, and the organizations responsible for infrastructural development for the industry (given in Table 1) must engage themselves with the stakeholders therein.

5. Expansion into the Countries with Civil Wars and Internal Conflicts

There are a number of Muslim countries marred by civil wars and internal conflicts, namely, Somalia, Libya, Iraq and Syria, where IBF has historically been almost negligible. These internal conflicts provide an opportunity for IBF to play a role in resolution of many political issues.

Incidentally, these countries have now had increasing incidence of poverty that could be tackled with the help of IBF. It is true that IBF has largely developed itself as an elitist phenomenon but the increase in income inequalities and absolute poverty in these and many other Muslim countries offer an opportunity for IBF to reform and make itself relevant to solution of socio-economic problems.

One way of promoting IBF in these countries is by way of engaging with the organizations involved in conflict resolution and other multilateral institutions like the UN, World Bank and IMF. Such an engagement will not be entirely new, as World Bank and IMF are already exposed to IBF on a limited scale. In fact, World Bank is already seriously looking into engaging itself with IBF. The establishment of the World Bank Global Centre of Islamic Finance at Istanbul is a step in this direction. Furthermore, World Bank has for a few years been co-organizing an annual conference on IBF in conjunction with AAOIFI.

The World Bank Global Centre is envisaged as a knowledge hub for developing Islamic finance globally, conducting research and training, and providing technical assistance and advisory services to the World Bank Group client countries interested in developing Islamic financial institutions and markets. On the occasion of the opening of the Centre on 30 October 2013, President of the World Bank Group, Jim Yong Kim, stated that the Centre is a symbol of the World Bank Group’s objectives of developing Islamic finance and maximizing its contribution to poverty alleviation and shared prosperity in client countries.

It is hoped that this Centre will become the cornerstone for the efforts of World Bank to promote IBF. With the countries like Turkey taking a leading role in designing and delivering cutting-edge technical assistance, advisory services, as well as generating and disseminating practical knowledge on how to make Islamic finance more relevant for growth and development, the Centre has a definite role to play in this respect. Given that the Centre is geographically located in a region where a number of Muslim countries are facing internal conflicts, the Centre has a huge potential to bring IBF to the forefront of policy-making in the region.

6. Development of Islamic Microfinance and Combating Poverty Through Financial Inclusion

Targeting the financially excluded can spur growth in IBF. However, the interest of the industry in this promising segment of the market is rather limited. Out of US$1.984 trillion assets under management of the IBFIs, less than 1% are in the microfinance sector.

There is a need that IBFIs should work with governments and other relevant institutions to provide community development finance. In this respect, the organizations like World Bank, IDB, ADB and African Development Bank can play an important role, and they must be engaged.

7. Development of Global Leadership in IBF

The likes of World Islamic Economic Forum (WIEF) have played an important role in providing a platform to the Muslim political leadership to get engaged in Islamic economic and financial issues in a popular fashion. Similarly, the establishment of Global Islamic Finance Leadership Award by Global Islamic Finance Awards (GIFA) has also helped in engaging the Muslim political leadership with IBF. However, a lot more needs to be done to develop, nurture and promote leadership in IBF. In conventional financial institutions and other organizations, promotion of IBF has been individual-driven. For example, HSBC got engaged in IBF due to the efforts of the likes of Iqbal Khan. Before that, the likes of DMI Trust and Albaraka Group were developed by Prince Mohamed Al Faisal and Sheikh Saleh Kamel, respectively. Hence, it is absolutely imperative to develop a new breed of Islamic bankers and finance experts who should serve as torch-bearers of IBF. Such new leaders must be developed through Islamic finance leadership programmes, which should be financed by all the stakeholders in the industry.

“One way of promoting IBF in these countries is by way of engaging with the organizations involved in conflict resolution and other multilateral institutions like the UN, World Bank and IMF.”

8. The Need for a Centre of Excellence for Research & Development in IBF

While the likes of IRTI and ISRA specialize in general and Shari’a-specific research in IBF, there is a need for setting up a specialized CoE focusing on growth and competition in the context of IBF. Investment in R&D is crucial to innovation which increases competitiveness and leads to growth. Islamic financial innovation must involve developing new Islamic financial products and services to increase the range of products and services to meet the more sophisticated and complex requirements of today’s consumers and businesses. It is also about improving the overall efficiency by which the products and services can be delivered. Innovation in IBF must also involve the continuous introduction of new structures that may contribute towards achieving economies of scale and scope. As mentioned above, it must also contribute towards creating new markets or expand the existing markets for Islamic products and services. Industry practitioners thus have an important role to promote innovation. Financial institutions need to equip their business strategies with research and development to design new innovative products and services. The innovative financial products and services that are credible, competitive and Shari’a-compliant would indeed find a ready market.

“Islamic finance has become a competitive form of financial intermediation that has been able to meet the differentiated requirements of our economies. In an environment of rapid change, a key factor that will influence the future prospects of the Islamic financial services industry will be the investments to build the foundations on which further progress can be achieved. Investing in the future, in research and development and in the development of talent and expertise will be the differentiating factor that will contribute to the effectiveness, resilience and competitiveness of the industry. This undertaking needs to be the joint responsibility of both the private and public sectors to mutually elevate the performance of the industry and thus increase its potential to contribute to wealth creation and prosperity of our nations.

Tan Sri Dr Zeti Akhtar Aziz, Governor of BNM, while addressing Islamic Bankers Forum, organized by CIBAFI at Kuala Lumpur in 2005.”

All this can be achieved by setting up a forum for well-informed debate and research about the future of IBF. The proposed forum should do this through a range of activities: written research, live discussion groups and networks, all focused on the latest developments in international finance and their relevance to IBF. The activities of the forum should be built around:

The post-financial crisis debate: how should the IBF be made relevant to the regulatory debate around the world and to promote IBF as a viable system to help bring stability in the global financial market?

The OIC block: prospects for the emerging financial centers in the Middle East and Far East Asia in a wider global context;

Technology: the impact of the internet and other new developments on Islamic financial markets, payment systems and bank strategies;

Governance: strengthening the global Islamic financial sector through advocacy of the institutions like IFSB and AAOIFI;

Financial inclusion: getting Islamic financial services out to those who need them but are currently excluded from financial sector; and

Risk management: identifying and managing emerging risks in the practices of IBF.

9. Looking for New Alliances

Having developed an alliance with the conventional Western mainstream banking and finance has helped IBF in receiving recognition and respect from the regulators and authorities in the countries where IBF is significant in operations, visibility and presence. While this has helped in the initial phases of development of the industry, going forward it will have to seek partnerships with other alternative forms of banking and finance.

Crowdfunding, for example, is gaining momentum in UK and other European countries, following an initial success in USA. As a number of crowdfunding platforms are equity-based, this alternative form of finance is in line with the general Shari’a requirements, and it will be good for IBF to explore possibilities of cooperation with the leading crowdfunding players. Also, crowdfunding is similar to branchless banking, which is a preferred model in the Western world for its cost-effectiveness and is being encouraged by a number of banking regulators in the developing and emerging markets as a drive to improve financial inclusion.

10. Development of IBF as an Integral Part of a Global Halal Economy

IBF is certainly an offshoot of Islamic economics. However, over the last four decades, IBF has gradually moved away from the movement of Islamic economics and has in fact emerged as a purely market-driven phenomenon. This decoupling of IBF and Islamic economics has not been seen favorably by a number of stakeholders, especially informed consumers. It is only recent that Dubai government has started a drive to make Dubai a global center of excellence for Islamic economy, and as a part of it has started promoting IBF. This is a step worthy of appreciation and emulation. In GIFR 2013, we argued that combining IBF with halal economic sector will increase the size of the combined Islamic financial and halal sector to more than the simple additive size of the two sectors.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

For greenfield growth, all the global Islamic infrastructure organizations should come together to devise a strategy that should involve engagement with the governments in the politically troubled Islamic countries to promote IBF. In countries like Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Libya, Somalia and Egypt, the governments should be convinced to use IBF as a tool for socio-economic reforms in the respective countries.

A level playing field for IBF is absolutely vital for its growth and further development. In countries where taxation regimes, property rights, land laws, and restrictions on banks to undertake direct businesses hinder development of IBF, Islamic banks will continue to face problems in initiation and operations even if somehow they are set up therein. Therefore, a concerted effort is required to engage with such countries politically to pave way for promotion and development of IBF. IBF has so far been a purely business phenomenon, but going forward a political dimension must be added to make it grow further and become more competitive.