INTRODUCTION

Delivering shareholder returns, while simultaneously strengthening capital reserves and keeping within the boundaries of Shari’a compliance, means that costs of Islamic banking institutions (IBIs) have to be managed aggressively and opportunities for growth needs to be identified carefully. New risks are emerging as Islamic banking moves from being a niche and expands into new territories and global regulatory regimes are becoming more stringent all the while demand for better customer services is ever increasing.

Given the relative smaller size of IBIs, complexity of legal documentation and uncertainty over regulatory treatment of at least some of its products (if not all), IBIs need a better understanding of risk and potential exposures. They must also ensure more effective control of capital. Many of Islamic banks and financial institutions (IBFIs) are newly set up, with product offerings that have some unique features. It is therefore quite likely that they are assuming some risks that are not fully quantifiable, especially as there is limited claims history and inadequate peril data. Risk management remains a challenge for most of the IBFIs as most of them are small in size and in a growing phase. As they try to operate low cost business models, they must rely on using information more effectively. Customer service is also becoming one of the few sources of real value addition in this new landscape. It, however, has its own implications for risk management.

As with other financial institutions, IBIs are exposed to different categories of risk – financial and otherwise. Islamic banks should have a comprehensive risk management and reporting process, including appropriate board and senior management oversight, to identify, measure, monitor report and control relevant categories of risk. A risk management framework is a set of guidelines and best practices that give practical effect of managing and mitigating the risks underlying the business objectives that IBIs may adopt.

Unlike conventional banks, risk management frameworks of IBIs also take into account appropriate steps to comply with Shari’a rules and principles and ensure the adequacy of relevant risk reporting. IBIs should have a sound process for executing all elements of risk management, including risk identification, measurement, mitigation, monitoring, reporting and control. This process requires the implementation of appropriate policies, limits, procedures and effective management of information systems (MIS) for internal risk reporting and decision-making that are commensurate with the scope, complexity and nature of IBIs’ activities.

This chapter looks at the different risks faced by an IBI and the risk management/mitigation practices. Risks faced by some of the leading Islamic banks are also analyzed. Future regulatory risks in terms of Basel III and the implications on Islamic finance industry will also be assessed.

ISLAMIC BANKING BALANCE SHEET AND RISKS

Before appreciating the risks specific to IBIs, an understanding of the nature of balance sheets of Islamic banks and the underlying contractual implications of the transactions is vital. Figure 1 is a snapshot of the statement of financial position of Bank Islami Pakistan, which is comparable with the statement of financial position of a conventional bank, HBL (Figure 2), for the same year, i.e., 2013.

Comparing the two statements, one may be inclined to conclude that the risk profiles of Islamic banks are similar to conventional banks. However, there are some unique risks associated with Islamic banks. Although consolidated statements of Islamic banks look similar to their conventional counterparts, the nature of the contracts used by Islamic banks expose them to a variety of risks in ways not applicable to conventional banking operations.

Although Islamic banks use a variety of financing instruments (like murabaha, salam, and ijara etc.), they use them in such a way that their risk exposure remains more or less similar to the credit-based financing services offered by conventional banks. Although the end result of risk management in IBIs may in fact be the same as a conventional bank, the risk management processes in the two cases are essentially different (see Box 9 at the end of this chapter).

Similarly, while the Islamic bank-depositor relationship is driven by a profit and risk-sharing structure, in practice IBIs attempt to bring their risk exposure to a level not very dissimilar to their conventional peers.

In this introductory section, therefore, we present a summary of various risks an Islamic bank may be exposed to, with reference to the particular financing contracts used by them. Risks on both the assets and liability sides are summarized in the following.

ASSETS SIDE RISKS

Market Risk

Market risk is the potential loss to the bank from positions taken in contracts where an Islamic bank is exposed to ownership and price risks. Market risk is the risk of losses in on- and off-balance sheet positions arising from movements in market prices, i.e., fluctuations in values of tradable, marketable or leasable assets (including sukuk) and in off-balance sheet individual portfolios (for example restricted investment accounts). This can happen, for example, when the bank takes up a true murabaha sale involving purchase of assets, which it will later sell on a credit basis. In some jurisdictions (like Malaysia), Islamic banks have applied the bay ‘ina (sale and buy-back) contract to avoid business risk so that profit rate on the murabaha contract is competitive with interest rates on conventional loans. The risks relate to the current and future volatility of market values of specific assets (for example, the commodity price of a salam asset, the market value of a sukuk, the market value of murabaha assets purchased to be delivered over a specific period) and of foreign exchange rates.

Figure 1: A Snapshot of Statement of Financial Position of Bank Islami Pakistan

Figure 2: A Snapshot of Statement of Financial Position of HBL Pakistan

Equity Investment Risk

Equity investment risk pertains to the management of risks inherent in the holding of equity instruments for investment purposes. Such instruments are based on the mudaraba and musharaka contracts. The capital invested through mudaraba and musharaka may be used to purchase shares in a publicly traded company or privately held equity or invested in a specific project, portfolio or through a pooled investment vehicle. In the case of a specific project, IBIs may invest at different investment stages.

The equity investment risk may broadly be defined as the risk arising from entering into a partnership for the purpose of undertaking or participating in a particular financing or general business activity as described in the contract, and in which the provider of finance shares in the business risk. In evaluating the risk of an investment using the profit sharing instruments of mudaraba, the risk profile of potential partners (mudarib) is a crucial consideration in the process of due diligence. Such due diligence is essential to the fulfilment of the IBIs’ fiduciary responsibilities as an investor of deposits on a profit sharing and loss-bearing basis (mudaraba).

These risk profiles include the past record of the management team and quality of the business plan of, and human resources involved in, the proposed mudaraba activity.

Credit Risk

Credit risk is generally defined as the potential that the counterparty fails to meet its obligations in accordance with the agreed terms. This definition is applicable to IBIs managing the financing exposures of receivables and leases (for example, murabaha, diminishing musharaka and ijara) and working capital financing transactions/projects (for example, salam, Istisna’ or mudaraba). IBIs need to manage credit risks inherent in their financings and investment portfolios relating to default, downgrading and concentration. Credit risk includes the risk arising in the settlement and clearing transactions.

IBIs should have in place a strategy for financing, using various instruments in compliance with Shari’a, whereby they recognize the potential credit exposures that may arise at different stages of the various financing agreement.

LIABILITIES SIDE RISKS

Profit Rate Risk

As Islamic banks do not deal with interest rate, it may appear that they do not have market risks arising from changes in the interest rate. Changes in the market interest rate, however, introduce some risks in the earnings of Islamic financial institutions. Financial institutions use a benchmark rate, to price different financial instruments. Specifically, in a murabaha contract, the mark-up is determined by adding the risk premium to the benchmark rate (usually the LIBOR). The nature of fixed income assets is such that the mark-up is fixed for the duration of the contract. As such, if the benchmark rate changes, the mark-up rates on these fixed income contracts cannot be adjusted. As a result, Islamic banks face risks arising from movements in market interest rate. Profit rate risk is also known as the rate of return risk.

Displaced Commercial Risk

Displaced commercial risk is the transfer of the risk associated with deposits to equity holders. This arises when, under commercial pressure, Islamic banks forego a part of its profit to pay the depositors to prevent withdrawals due to a lower return (AAOIFI, 1999). Displaced commercial risk implies that although the bank may operate fully in compliance with the Shari’a requirements, it may not be able to pay competitive rates of return as compared to its peers and other competitors. Depositors will in this instance have the incentive to seek withdrawal. To prevent it from happening, the owners of the bank will need to apportion part of their own share in profits to the investment depositors.

A variable rate of return on savings/investment deposits introduces uncertainty regarding the real value of deposits. Asset preservation in terms of minimizing the risk of loss due to a lower rate of return may be an important factor in the depositors’ withdrawal decisions. From the bank’s perspective, this introduces a “withdrawal risk” that is linked to the lower rate of return relative to other financial institutions.

Fiduciary Risk

A rate of return that is lower than the market rate also introduces fiduciary risk, which is when depositors/ investors interpret a low rate of return as a breach of investment contract or mismanagement of funds by the bank (AAOIFI, 1999). Fiduciary risk can be caused by a breach of contract by the Islamic bank. For example, the bank may not be able to fully comply with the Shari’a requirements of various contracts. While the justification for the Islamic bank’s business is compliance with the Shari’a, an inability to do so or not doing so wilfully can cause a serious confidence problem and deposit withdrawal.

The following are some examples of fiduciary risk:

- In case of partnership-based investment in the form of mudaraba and musharaka on the assets side, the bank is expected to perform adequate screening and monitoring of projects, and any deliberate or intentional negligence in evaluating and monitoring the project can lead to fiduciary It becomes incumbent on management to perform due diligence before committing the funds of investors-depositors.

- Mismanagement of the funds of current account holders, which are accepted on a trust (amana) basis, can expose the bank to fiduciary risk as It is common practice for Islamic banks to use the funds of current account holders without being obliged to share the profits with them. However, in the case of heavy losses on the investments financed by the funds of current account holders, the depositors can lose confidence in the bank and decide to seek legal recourse.

- Mismanagement in governing the business by incurring unnecessary expenses or allocating excessive expenses to investment account holders is a breach of the implicit contract to act in a transparent

OPERATIONAL RISKS FACING IBFIs

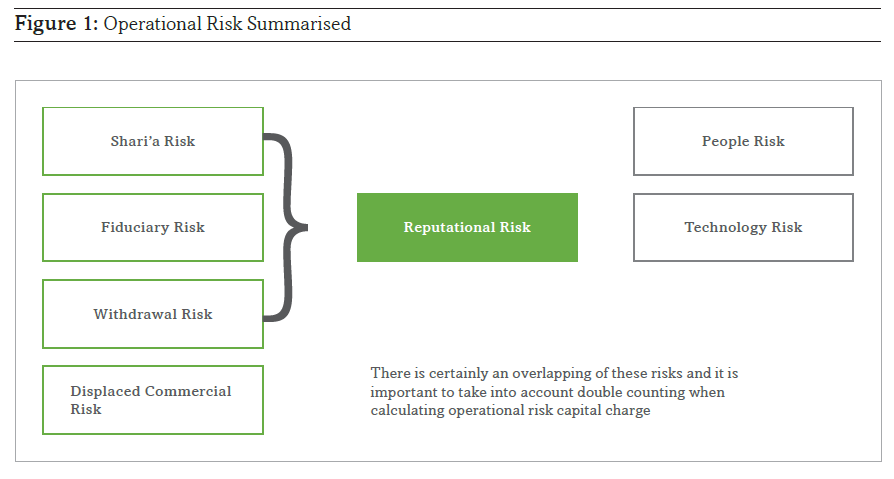

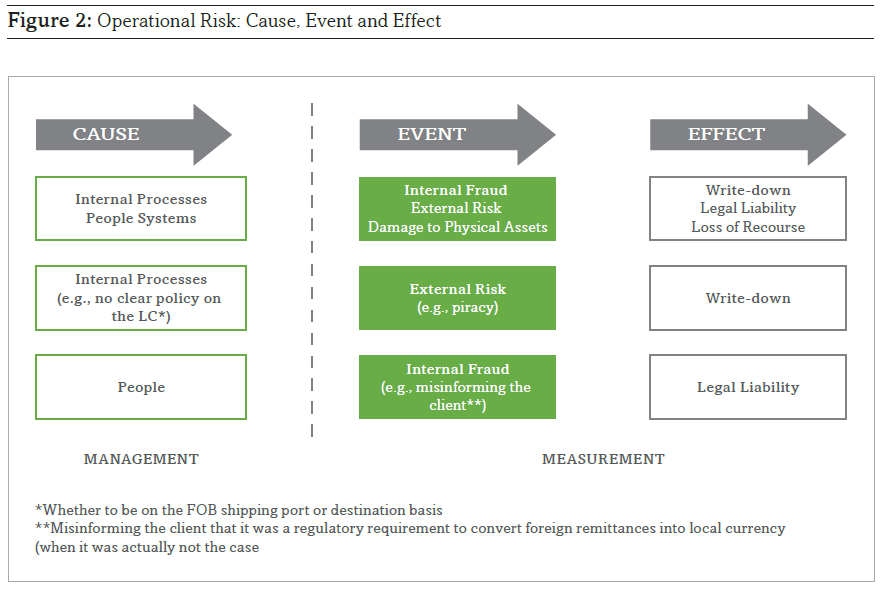

Although one may argue that operational risk facing IBFIs cannot be significantly different from what other banks and financial institutions have to deal with in their operations in normal circumstances, it can however become more significant and complicated compared to conventional banks because of their unique contractual features and general legal environments. Specific aspects and diversity of contracts could raise the operational risk of Islamic banks. Thus operational risk in IBFIs has attracted more attention from the regulators, practitioners and academics over the last decade.

The most significant of operational risks facing IBFIs relates to Shari’a compliance and the adverse reputational consequences of it.

Shari’a Non-compliance Risk

Shari’a non-compliance risk is the risk that arises from an IBFI’s failure to comply with the Shari’a rules and principles. As compliance with Shari’a is a basic requirement for an IBFI, Shari’a risk is related to the structure and functioning of Shari’a boards at the institutional and systemic level.

This risk could be due to non-standard practices in respect of different contracts in different jurisdictions, and may in fact be due to the failure to comply with Shari’a rules. Differences in the interpretation of Shari’a rules result in differences in financial reporting, auditing, and accounting treatment. For instance, while some

Shari’a scholars consider the terms of a murabaha or istisna’ contracts to be binding on the buyer, others argue that the buyer has the option to decline even after placing an order and paying the commitment fee. While different schools of thought consider different practices to be acceptable, the bank’s risk is higher in non-binding cases and may lead to litigation in the case of unsettled transactions.

The relationship between the bank and the investors-depositors is not only that of an agent and principal; it is also based on an implicit trust between the two that the agent will respect the desires of the principal to comply fully with Shari’a. This relationship distinguishes Islamic banking from conventional banking and is the sole justification for the existence of Islamic banks. If the bank is unable to maintain this trust and the bank’s actions lead to non-compliance with Shari’a, the bank risks breaking the confidence of the investors- depositors. Therefore, the bank should give high priority to ensuring transparency in compliance with Shari’a and take actions to avoid lack of compliance.

Islamic Contracts and Shari’a Compliance

There are at least six basic principles that are taken into consideration while executing any Islamic banking transaction. These principles differentiate a financial transaction from a riba/interest-based transaction to an Islamic banking transaction:

- Sanctity of contract: Before executing any Islamic banking transaction, the counterparties have to satisfy whether he transaction is halal (valid) in the eyes of Shari’a. This means that Islamic bank’s transaction must not be invalid or An invalid contract is a contract, which by virtue of its nature is invalid according to Shari’a rulings. Whereas a voidable contract is a contract, which by nature is valid, but some invalid components are inserted in the valid contract. Unless these invalid components are eliminated from the valid contract, the contract will remain voidable.

- Risk sharing: Islamic jurists have drawn two principles from the sayings of Prophet These are “al-khiraj bi al-daman” and “al-ghunum bi al-ghurum”. Both the principles have similar meanings that no profit can be earned from an asset or a capital unless ownership risks have been taken by the earner of that profit. Thus in every Islamic banking transaction, the Islamic financial institution and/or its deposit holders take the risk of ownership of tangible assets, real services or capital before earning any profit therefrom.

- No Riba/interest: Islamic banks cannot be involved in riba/interest-based They cannot lend money to earn additional amount on it. However, as stated in point 2 above, it earns profit by taking risk of ownership of tangible assets, real services or capital and passes on this profit/loss to its deposit holders who also take the risk of their capital.

- Economic purpose/activity: Every Islamic banking transaction has certain economic purpose/activity. Further, Islamic banking transactions are backed by tangible assets or real

- Fairness: Islamic banking inculcates fairness through its Transactions based on dubious terms and conditions cannot become part of Islamic banking. All the terms and conditions embedded in the transactions are properly disclosed in the contract/agreement.

- No invalid subject matter: While executing an Islamic banking transaction it is ensured that no invalid subject matter or activity is The law of the land may allow some subject matter or activity but if the same are not allowed by Shari’a, an Islamic bank cannot finance these.

Any transaction that does not adhere to the aforementioned rules, would be considered Shari’a non-compliant and thus be invalid.

COUNTERPARTY RISKS UNIQUE TO ISLAMIC FINANCING CONTRACTS

In this section, we discuss some of the risks inherent in some Islamic modes of financing.

Murabaha Financing

Murabaha is the most used Islamic financial contract. The most important counterparty risk specific to murabaha arises due to some of the unsettled operational aspects of the contract in many countries. For example, it still remains a matter of juristic debate whether murabaha is a binding contract at the time of the purchaser putting an order to buy. Although AAOIFI Shari’a standard on murabaha li al-amr bi al-shira (murabaha to the purchase orderer) clearly proclaims it to be a binding contract, in many jurisdictions it is important to incorporate an explicit reference to this Shari’a standard to avoid any potential disputes. Another potential problem in a sale contract like murabaha is with reference to late payments by the counterparty. An Islamic bank cannot, in principle, charge anything in excess of the agreed-upon price. However, in the contemporary practice of IBF, it is allowed to discourage wilful default. It is, therefore, important to incorporate default penalty carefully in such a way that it does not dilute the spirit of Islamic finance, on one hand side, and protects the interests of the bank, on the other hand, in such a way that all the Shari’a requirements of charging penalty are fulfilled.

Salam Financing

There are at least two important counterparty risks in salam. A brief discussion of these risks is as follows:

The counterparty risks can range from failure to supply on time or supply at all or to supply the same quality of goods as contractually agreed. Since salam is a commodity-based contract, the counterparty risks may be due to factors beyond the normal credit quality of the client. For example, the credit quality of the client may be very good but the supply may not come as contractually agreed due to natural calamities or any other factors beyond control of the salam seller. In case of agricultural commodities, the produce is exposed to catastrophic risks, and the counterparty risks are expected to be more than usual in salam.

- Salam contracts are in general neither exchange-traded nor traded over the These contracts are written between two parties to a contract. Thus, all the salam contracts end up in physical deliveries and ownership of commodities. These commodities require inventories, which expose the banks to storage costs and other related with price risks. Such costs and risks are unique to Islamic banks.

Istisna’ Financing

When extending istisna’-based finance, the bank exposes its capital to a number of specific counterparty risks:

- The counterparty risks faced by the bank under istisna’ from the supplier’s side are similar to the risks mentioned under There could be a contract failure regarding quality and time of delivery.

However, the subject matter of istisna’ is more in the control of the counterparty and less exposed to natural calamities as compared to salam. Therefore, it can be expected that the counterparty risk of the sub-contractor of istisna’, though substantially high, is less severe compared to that of salam.

- The default risk on the buyer’s side is of a general nature, namely, failure in paying fully on

- If the istisna’ contract is considered optional and not binding as the fulfilment of conditions under certain fiqhi jurisdictions may require, there is a counterparty risk as the supplier maintains the option to rescind the contract.

- Like in a murabaha contract, if the client in the istisna’ contract is given the option to rescind the contract and decline acceptance at the time of delivery, the bank will be exposed to additional

These risks exist because an Islamic bank, when entering into an istisna’ contract assumes the role of a builder, constructor, manufacturer and supplier. Since the bank does not specialize in these areas, it relies on subcontractors.

Musharaka/Mudaraba Financing

Many academic and policy-oriented writings consider that the allocation of funds by Islamic banks on the basis of musharaka and mudaraba is preferable compared to the fixed return modes of murabaha, leasing and istisna’. But in practice, Islamic banks’ use of the equity modes is minimal. This is considered to be due to the very high credit risk involved.

Business risk is expected to be higher under the partnership modes due to the fact that there may in many cases be no collateral requirement. Furthermore, there is a high level of moral hazard and adverse selection and the banks’ existing competencies in project evaluation and related techniques are limited. Institutional arrangements such as tax treatment, accounting and auditing systems, and regulatory framework are all not in favour of a larger use of these modes by the banks.

One possible way for Islamic banks to reduce the risks in profit-sharing modes of financing is by taking a control position in the companies they invest in. Before investing in projects on a partnership basis, the bank needs to carry out a thorough feasibility study. By holding an equity stake in the investee company and hence commanding a director’s position, an Islamic bank can essentially get involved in decision-making and the management of the investee company. As a result, the bank will be able to monitor the use of funds by the project more closely and reduce the moral hazard problem.

Some economists however, argue that by not opting for these modes, banks are actually not benefiting from portfolio diversification and hence taking more risks rather than avoiding risks. Moreover, the use of the partnership modes on both sides of the banks’ balance sheets will actually enhance systemic stability as any shocks on the asset side will be matched by an absorption of the shock on the deposit side. It is also argued that incentive-compatible contracts, which can reduce the effect of moral hazard and adverse selection, can be formulated.

Internal Shari’a Control Mechanism for Ijara Financing

Ijara is the lease of a non-consumable asset. The difference between an ijara contract and a conventional lease is that the ownership and all associated risks remain with the lessor till the end of the ijara term. While in a conventional lease, ownership of the leased asset remains with the lessor, the lessee is responsible for the maintenance and other such responsibilities. An ijara contract makes the lessor responsible for all such matters and the associated costs.

Shari’a control mechanism in this case should ensure:

The bank must document the transaction properly;

The asset is specified and known – proper asset description and date of delivery must be mentioned in the relevant document;

In case of ijara wa iqtina’, it is advisable that the total costs of the asset must be determined at the time of the execution of the lease agreement and will include all ownership related costs, e.g., takaful (insurance) duties, taxes, transportation;

The ijara period is known – specified date of each monthly rental becoming due must be clearly mentioned in the rental schedule;

A proper mechanism is agreed upon in case of need to change rental rate;

The ijara is concluded correctly and the ownership is transferred to the customer (in case of ijara wa iqtina’);

- The responsibility of risk is clearly known to both the bank and customer;

- The nature of rentals is clearly known, e., in advance or in arrears;

The rental payment starts after the delivery of the asset, not from the contract date – in case the asset requires some time for installation, the rentals will start after the asset is in a usable condition;

Rentals can be fixed or variable – in case of variable rate rental, the rentals for the first period must be fixed at the time of execution of the ijara agreement and will change accordingly to a known formula;

The asset is transferred (by means of gift or sale) through a separate contract at the end of the lease term (in case of ijara wa iqtina’).

Internal Shari’a Control Mechanism for Diminishing Musharaka Financing

Diminishing musharaka is a composite product that comprises shirka (joint ownership), ijara rental and bai’ (sale). Rules of the mentioned contracts need to be ensured for this product.

Most processes are the same as in the ijara contract. Shari’a control mechanism for this should ensure:

- The steps of implementation should be defined in advance, e.,

- shirka first then ijara and then sale;

- This arrangement should not be used for cash financing;

In a sale-and-lease-back transaction, the sale of units will start after completion of one year to avoid buy-back arrangement; and

There must be a mechanism to deal with early maturity and balloon payments.

Liquidity Risk Management

The risk management functions relating to treasury operations are mainly performed by the middle-office. The concept of middle-office has recently been introduced so as to independently monitor, measure and analyze risks inherent in treasury operations of banks. Besides, the unit also prepares reports for the information of senior management as well as a bank’s Asset and Liability Management Committee (ALCO). Basically the middle-office performs risk review function of day-to-day activities. Being a highly specialized function, it should be staffed by people who have relevant expertise and knowledge.

A middle-office setup, independent of the treasury unit, could act as a risk monitoring and control entity reporting directly to top management. Keeping tabs on the Value-at-Risk (VaR), ensuring adherence to external and internal guidelines and evolving risk-monitoring systems would be some responsibilities of such a setup. The methodology of analysis and reporting may vary from bank to bank depending on their degree of sophistication and exposure to market risks. These same criteria should govern the reporting requirements demanded of the middle-office; which may vary from simple gap analysis to computerized VaR modelling.

Middle-office staff may prepare forecasts (simulations) showing the effects of various possible changes in market conditions related to risk exposures. Banks using VaR or modelling methodologies should ensure that the results are consistent.

Regular information flow from the head of treasury to the head of middle office department is required in discharging these responsibilities efficiently and effectively. Investment in IT as a tool for decision-making allows banks to respond in real time to operational needs. However, the ability to monitor and respond manually in the absence of IT tools is still required.

The roles of an effective middle-office operation are to ensure:

A systematic approach to risk control for all products;

- Understanding of the necessary legal, documentary and regulatory frameworks;

- Effective interaction with the front office and other departments;

- The preparation and support for the introduction of new products;

- The implementation of effective accounting, reporting and MIS; and

- Comparing the “best practices” of middle-office

Risk assessment should cover all risks facing the bank and the consolidated banking organization (i.e., Shari’a risk, country and transfer risk, market risk, interest rate risk, liquidity risk, operational risk, legal risk and reputational risk). Financial controls may need to be revised to appropriately address any new or previously uncontrolled risks. Areas of potential conflicts of interest should be identified and minimized, subject to careful and independent monitoring.

Control activities should include:

Top level reviews;

- Appropriate activity controls for different departments or divisions;

- Physical controls;

- Checking for compliance with exposure limits and follow-up on non-compliance;

- A system of approvals and authorizations; and

A system of verification and reconciliation.

There should be an effective and comprehensive internal audit carried out by operationally independent, appropriately trained and competent staff. These systems, including those that hold and use data in an electronic form, must be secure and monitored independently, and supported by adequate contingency arrangements. The internal audit function should report directly to the board of directors or its audit committee, and to senior management. Deficiencies, whether identified by business line, internal audit, or other control personnel, should be reported in a timely manner to the appropriate management level and addressed promptly. Material internal control deficiencies should be reported to senior management and the board of directors.

Market/Business Risk Management

Market risk in Islamic banking refers to the potential loss arising from a trading position – such as sale and purchase, leasing or equity. All these positions involve ownership of assets whose value fluctuates due to market forces. For example, in a murabaha-financing contract, the bank purchases an asset on cash basis in order to sell it on to the customer on credit terms. In ijara, the bank buys an asset and further leases it. When dealing in equities, using a musharaka contract, the bank purchases common stocks with a plan to sell them and realize capital gains.

All these positions involve the purchase of assets and consequently incurring market risk before selling them further. In ijara, the ownership risk remains with the lessor throughout the rental tenure.

Trading positions in Islamic banks are based on the certainty of sale and purchase activity between the bank and the client. In other words, the bank will enter into a trading position only when there is reasonable certainty (after due diligence) of disposing the asset at a profit. This Islamic banking practice is different from retail trading where merchants have no guarantees as such and are fully exposed to market movements and price volatilities.

While ownership of assets can be evident in Islamic financing through title transfer, Islamic banks have been able to eliminate volatility in asset value (i.e., business risk) by instantaneous sale and purchase. This feature is common in murabaha, bay al-‘ina and tawarruq financing, where instantaneous asset exchanges means the bank does not incur an additional capital charge. The bank further reduces its risk position by making sales binding, where financing is initiated only when the client has confirmed the purchase of the asset and, hence, it is highly unlikely that the bank will end up holding unwanted inventories. Some argue that this practice is against the spirit of Islamic economic theory but this argument, whether true or false, is not the point of discussion of this report.

Using murabaha financing as an example, we see how this works:

The client negotiates with a vendor to purchase an Asset A. He then seeks a bank facility to finance the purchase. Suppose the price of Asset A is $100,000. Using murabaha, the bank appoints the client as an agent to purchase the asset on the bank’s behalf. It is subsequently sold to the client at a credit price of $100,000 plus a profit margin, say $130,000 for a 10-year facility. The bank’s ownership of the asset is evident as the bank makes the purchase directly from the vendor. There is practically no holding period as the vendor makes delivery of the asset to the customer once the facility is approved.

Stage 1: Client negotiates with a vendor (1 February 2015)

Stage 2: Client applies for the financing facility (1 February 2015)

Stage 3: Bank approves the financing facility (6 February 2015)

Stage 4: Bank appoints the client to buy asset on its behalf and pays the vendor (6 February 2015)

Stage 5: Vendor delivers A to the client (6 February 2015)

Stage 6: Periodic cost + mark-up payments are made by the client till maturity period

Shari’a Governance & Disclosure

One of the key concerns is insufficient disclosure of Shari’a governance in the annual reports of IFIs. Issues such as conflict of interest of Shari’a board members within an IFI and with other IFIs, among other issues, are largely ignored. Inconsistency between jurisdictions aside, there appears to be insufficient disclosure of IFIs’ Shari’a governance and other key disclosures in annual reports.

IFIs should set additional requirements for disclosures in their annual reports relating to income purification and disbursement to charities, due to the inherent sensitivities associated with these funds. Additional disclosures can include:

- Value of impermissible income and the late penalty fees relating to the period, including any contingent amounts;

Purification amounts that have been disbursed during the period with explanations for any non-disbursed amounts;

Reporting on the nature of the charities supported and their social impact;

Disclosure of fees paid to the members of Shari’a supervisory board (SSB) within the institution’s annual reports (split by audit and non-audit), similar to disclosures of fees paid to external auditors;

Related party transactions where Islamic financial institutions have close connections with any of the receiving charitable organizations; and

Disclosure by all personnel involved in the audit (SSB, internal Shari’a unit members, etc.) of any interests such as shareholdings, a relative/related party working in a senior role in the institution, commercial relationships as a customer or supplier (either with the individual or with a related/linked company of which the SSB or any relative may be a director), etc.

BASEL III – IMPLICATIONS FOR IBIs

Liquidity Requirements and Implications

In both Basel I and Basel II, liquidity risk received only limited attention. The entire Basel framework only looked at the asset side of the balance sheet. Risks arising from the liability side (including liquidity risk alongside other risks, such as interest rate risk of the banking book), for instance, are not subject to regulatory capital requirements. They are instead disciplined under Pillar 2, whereby banks are required to undertake the ICAAP (Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process), i.e., a calculation of the amount of capital (called internal capital) they deem sufficient to support virtually all their risks. Pillar 2 requires that the ICAAP includes liquidity risk. However, this provision has resulted in an inconsistency. After years of sterile debate on the possible methodologies for calculating internal capital for liquidity risk, it has been generally accepted that capital is not a suitable mitigating factor for liquidity risk. As a result, the current Basel II framework does not in effect address liquidity risk.

Liquidity risk originates from the mismatch between the timings of cash inflows and outflows. As such, it is fundamentally inherent to the banking business. In fact, one of the key functions of the banking industry in a modern economic system is to allow the reallocation of financial resources from the liquid sectors (those which have excess financial resources to invest) to the illiquid ones. In the view of Bank for International Settlements (BIS) the new requirements will have to be stringent. Capital and liquidity resources should be such that the financial system must have the strength to withstand a crisis of the size and persistency of the recent one, without public support. The Basel Committee proposes to introduce two new ratios (Liquidity Coverage Ratio and Net Stable Funding Ratio) that banks must maintain as a minimum at virtually all times to help ensure they maintain sufficient liquidity to withstand cash obligations even under stress.

Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) focuses on the shorter end of the time horizon and is aimed at helping to ensure that each bank owns liquid resources to such an amount that short-term cash obligations are fulfilled even under a severe stress. The ratio requires banks to hold enough liquid assets to offset the sum of all cash outflows expected over the next 30 days.

Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) looks at a medium-term horizon and focuses on the structural balance between maturities of a bank’s assets and liabilities. It is aimed at preventing banks from exposing themselves to extreme maturity transformation risks by funding medium and long-term assets with very short-term liabilities.

With the deficiency of alternative Shari’a-compliant liquidity management tools and the absence of a developed Islamic money market, operations of an Islamic bank could be adversely affected. The idea that IFIs have sufficient liquid reserves and that they are immune to liquidity risk has proven to be wrong with the default of many sukuk. Islamic banks have daily liquidity requirements arising from basic activities such as withdrawals or credit payments. Therefore, Islamic banks, especially those with multiple lines of businesses, will have to aggregate, reconcile, and analyze data to gain an accurate measure of their liquidity risk exposures. Accordingly, LCR and NSFR ratios should be used on an ongoing basis to help monitor and control liquidity risk and prevent the case where Islamic banks are not able to adequately meet the liquidity gap in their obligations without incurring unacceptable costs or losses. The new framework imposes these banks to report their LCR at least once a month, with the operational capacity to increase the frequency to, weekly or even daily, in stressed situations, and to calculate and report the NSFR at least quarterly.

Capital Requirements and Implications

With Basel III, BIS has decided to increase the importance of what we name the Tier 1 Capital, which is in fact the common equity and some hybrid capital (strict eligibility criteria). The definition of the Tier 2 Capital is reduced consequently (for example, issuances without loss absorbency at the point of non-viability are progressively excluded from Tier 2 Capital). The Tier 3 is abrogated. In terms of capital requirements, the new measures include the installation of a leverage control, which will put an upper limit to the risk a financial institution will be able to take. Under Basel III, banks will be required to increase their Tier 1 capital to at least 6% of risk-weighted assets (RWA). Most of this capital will need to be in the form of common equity. And by 2015, at least 4.5% RWA should be used by banks as a maximum for market shock absorbency. In addition, banks will be required to hold a capital conservation buffer of 2.5% to withstand future periods of stress, bringing the total common equity requirements to 7%. The purpose of this buffer is to ensure that banks maintain an amount of capital that can be used to absorb losses during periods of financial and economic stress.

For Islamic banks, capital structure is not the same; banks cannot pay or earn interest on their financial instruments. The consequence is that the banks mobilize and utilize funds using Shari’a-compliant instruments or contracts that are not used by their conventional counterparts. The portion of minimum capital charges to shareholders in Islamic banks seems actually to be lower than in conventional banks. This is explained essentially by the fact that mudaraba contracts (profit sharing investment accounts) do not charge the mudarib for losses not resulting from negligence, fraud or violation of contract including violation of normal and customary professional standard practices. This means that while the parameters of risk weighing and minimum equity calculation in Islamic banks may be the same as in their conventional counterpart, the capital burden on shareholders should be lower than that in conventional banks.

In term of investments, Islamic banks have to take into account equity investment risk, related mostly to mudaraba and musharaka instruments held by the bank. As credit-based products are predominant in Islamic banking business models, these banks are much exposed to credit risk resulting from the uncertainty of the counterparties’ ability to meet their debt obligations.

Bottom Line

It is hard to completely evaluate the possible effects of the implementation of Basel III reforms on Islamic banks at this stage. Even though the Basel III reforms are expected to directly affect capitalization and funding levels, the reforms seem to be generally accepted within the Islamic financial community. Organizations such as IFSB are already revising their regulatory and supervisory rules in line with the Basel III framework. The magnitude of the impact will basically depend on other factors, such as the jurisdiction where the IBI operates and the nature of banking activities within each institution.

THE WAY FORWARD

The challenge going forward for Islamic banks is to establish a cultural mindset and operating framework that embeds balance sheet risk – something beyond the regulatory requirements set out under Basel III.

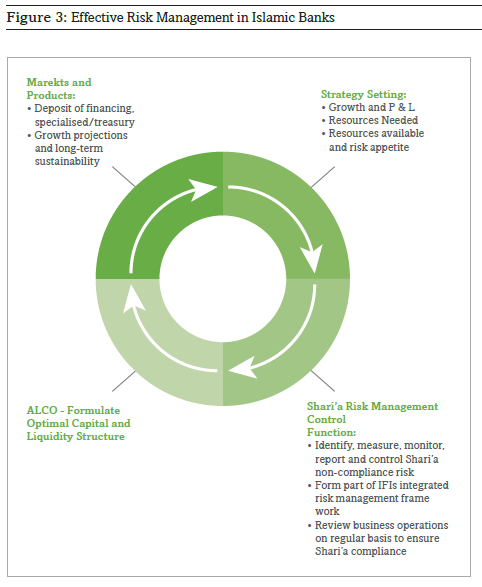

As regulations become more stringent and the market becomes saturated, banks need to enforce an inclusive risk management ensuring effective teamwork. Figure 3 (on next page) gives a brief illustration of what might be needed for Islamic banks to be more effective.

As more complex deals are being executed and more complicated products being developed, if any institution, inside or outside the Islamic financial services industry, deserves scrutiny, it is the Shari’a advisory function.

“As more complex deals are being executed and more complicated products being developed, if any institution, inside or outside the Islamic financial services industry, deserves scrutiny, it is the Shari’a advisory function. Indeed, Shari’a risk is the most paramount in operational risk management. Hence, development of effective Shari’a governance regimes on global, national and institutional levels are imperative.”

Indeed, Shari’a risk is the most paramount in operational risk management. Hence, development of effective Shari’a governance regimes on global, national and institutional levels are imperative. In this respect, apart from a Shari’a audit to check compliance with the Shari’a governance frameworks provided by the Shari’a board, a fatwa audit is also proposed in countries where no centralized SSB is instituted. This would be an independent audit carried out to determine what reasoning was used by the SSB in deeming a deal, product or transaction as Shari’a-compliant. This, along with strict adherence to Shari’a standards issued by AAOIFI and Shari’a governance framework being developed by IFSB, can be a revolutionary step in tackling the creeping cynicism about Islamic finance among Muslims.

Being suitably qualified requires both a minimum level of knowledge and skill as an entry criterion, and also the need to have ongoing training. Shari’a scholars working as advisors to an IBFI also need to consider the risks of litigation over the advice they provide as increasing litigation activity related to Islamic finance is being seen in courts. Initiatives in the Islamic finance industry specifically addressing the issue of competence include “fit and proper” criteria set by industry regulators. However, it is preferred that central Shari’a boards be constituted in all the countries where IBF is significant. This will ensure that no tension crops up between Shari’a scholars and other stakeholders involved in IBF.

Islamic banks should also bear in mind the lack of an effective consumer relations policy, focusing on aspects such as anticipating a change in consumer needs and how they will defer in the next 5 years, how to respond to such changes and how to target new consumer groups. Most of the global Muslim demography is young and the consumer base mostly consists of Gen-Y individuals. These individuals tend to be higher educated and critical; they often have above average incomes and are extensive users of technology. Therefore, use of technology in complicated products and the use of social media for marketing campaigns should be employed effectively.

BOX 9: SPECIFIC RISKS FACING IBFIs

Besides standard risks that Islamic as well as conventional banks face and manage, there are other risks that are specific to Islamic banks. Some of these risks are entirely new (like commercial displacement risk) and others are new yet fall under existing categorizations of risk (like credit risk, market risk and interest rate risk etc.). These risks are specific to Islamic banks with respect to the Shari’a compliance requirements. Hence, these could be treated as specific operational risks faced by IBFIs. Although these risks may prove fatal in some extreme cases, the management of IBFIs and their consultants so far have failed to emphasize sufficiently on their importance.

Islamic banks would be exposed to these specific risks due to a number of reasons, including the issuance of certain Shari’a resolutions by its own Shari’a supervisory committee and/or that of a national Shari’a advisory body (or even an individual Shari’a scholar), issuance of new guidelines by a central bank or another financial regulator, or due to issuance of unfavourable decisions by a court of law. In such a scenario, one must expect an adverse impact on profits and revenues of the concerned Islamic bank.

On the other hand, on a lighter note, an Islamic bank may be exposed to a specific risk due to customer defection or customer dissatisfaction. If such a situation arises then this might result in negative marketing (i.e., word of Mouth) and if remained unchecked for a long period then it could lead to permanent loss in the market share.

In this Box, we focus on some of the most important risks specific to IBFIs.

Factor 1: Risk of Underlying Asset

Most of the financing transactions in IBF are based on selling or leasing of an underlying asset. In fact, bearing the risk of ownership of an underlying asset entitles an IBFI to claim revenues generated from the sale of the underlying asset. The specific risk that an IBFI faces is a possible or potential loss of the underlying asset prior to execution of sale/lease contract. According to Shari’a, an IBFI can claim any amount of profit provided it bears the risk of the underlying asset at the time of selling or leasing the same.

As per Shari’a rulings, Islamic banks cannot sell an asset before getting the risk of the underlying asset transferred to itself. For example, if an Islamic bank buys a car from a dealer and if anything goes wrong with the car prior to executing an auto murabaha contract then Islamic bank has to bear the loss.

Similarly, in shares financing (as a substitute to personal financing), Islamic bank is exposed to high degree of price risk in case the customer rejects or defaults in signing the murabaha or musharaka of shares. Such kind of risks could be mitigated through various risk mitigation methods. The most common risk mitigation method in this respect is to ensure that the Islamic bank (as seller) executes sale of the underlying asset to the customer (as buyer) in the fastest possible time. Obtaining customer’s acceptance through implied consent would facilitate Islamic bank to transfer such kind of risk at the fastest possible way.

As per Shari’a rulings, deferment of risk transfer for a specific asset is not permissible. For example, Islamic bank cannot agree to sell a specific asset today where the risk will be transferred after one month. This could be addressed through timing of risk where execution of the sale of the underlying asset is scheduled only when the seller is willing to part away from the underlying asset.

As per Shari’a rulings, once risk of the underlying asset is transferred to the customer (as buyer) then the Islamic bank (as seller) has no Shari’a right of reselling it to other party or the same buyer at profit. Hence many Islamic bank face losses when murabaha customers delay in settling their payments by few months. Islamic banks do not wish to qualify such delay as events of default but still they suffer losses due to fixing the price of murabaha. This could be mitigated through appropriate pricing of risk whereby the Islamic bank (as seller) has to agree on the best rate of return/ yield at the time of transferring the risk to the customer (as buyer).

Factor 2: Specific Credit Risk

Credit risk specific to Islamic banks can be defined as the financial loss that an IBFI suffers when a customer defaults. In conventional banking, when a customer is late on payments, the lender benefits in terms of default penalty and the additional interest that the customer has to pay to bring their account in order. In some cases, delay in payment is expected and welcomed, as it brings additional benefits to the lender (as is the case in the credit card business wherein credit card provider actually awaits a transactor to become a revolver). As default penalty is not allowed in IBF, and where it is imposed, the finance provider cannot benefit from it except to the extent of the direct administrative costs associated with it, the credit risk for IBFIs includes additional loss of income due to default.

Generally, customers of Islamic banks have two kinds of financial obligations: a) debt settlement; and

- b) periodic purchase or

In debt settlements (for example settling dues of murabaha, istisna’ and salam, etc.), the customer has to settle the outstanding financial obligation irrespective of availability or non-existence of the underlying asset. Hence, if a car sold on a murabaha basis is destroyed, even then the due price has to be paid by the customer. However, on the downside, Islamic bank cannot claim any extra returns over the contracted sale price or the outstanding debt.

For example, during financial crises, Islamic banks in Dubai had to stick to the capped profit amount agreed upon at the time of executing murabaha.

This incurred heavy losses to a number of Islamic banks that financed properties under construction, which got delayed on delivery. This is a major risk facing IBFIs using murabaha as a dominant tool of financing in their business.

This is one of the reasons that an increasing number of IBFIs have now started preferring other modes of financing, which offer flexibility in the wake of an adverse event. One solution that has been in practice in some countries is the use of periodic purchases and sales contracts. Ijara-based leasing is another risk mitigation tool. In cases of periodic sales and leases, returns for the coming periods can be adjusted to compensate the Islamic bank for loss due to customer’s default or changing financial conditions. For example, in case of ijara, it is possible to increase the rent of the subsequent months, followed by a default on part of a customer. Similarly, in case of a periodic sale contract, the sale price can be increased in subsequent sales if a regular customer happens to default on a particular obligation.

However, it should be noted that there is a possibility of trade-off between specific credit risks and the specific risks arising from the ownership of the underlying assets. While moving to ijara-based products may help in reducing credit risk, it is expected to increase the risks associated with the underlying assets. Similarly, moving to multiple and periodic sales to mitigate credit risk is also expected to increase likelihood of operational risk (in terms of mistakes, errors and omissions by the bank’s personnel).

Given this trade-off, care must be exercised to decide on the contract choice, and other factors like price volatility, customer’s credit history, and the expertise level of the bank staff must also be taken into account. If, for example, downward price volatility is the dominant factor, then one-off murabaha transaction may be a better choice. If, however, customer’s default is likely (and is still within the acceptable risk threshold), then periodic sales and ijara contracts may be more feasible. If, on the other hand, an IBFI faces excessive incidence of operational risk, simple one-off murabaha transactions may be preferred.

Factor 3: Risk of Human Capital

All banks and financial institutions face people risk, which is categorized under operational risks. In case of IBFIs, this risk has an additional dimension, given the Shari’a compliance requirements. After all, IBF is driven by Shari’a sensitivity of customers. If IBFI customers perceive employees of such institutions less than committed to IBF, this will adversely affect their patronage and custom.

In recent times, a number of Islamic banks in the Middle East have suffered losses due to irregularities in operations and inadequacy of policies adopted by the top management that was not particularly committed to Islamic banking. Similarly, all the Islamic banks set up in UK had CEOs who came from non-Islamic background. These CEOs were gradually replaced with Muslim CEOs who are seen more favorably by the users of Islamic financial services. A number of Shari’a boards advise their banks to choose pious Muslims to lead their businesses, an advice that has not been taken seriously in many cases though. In South Africa, there has been at least one case where a top manager of Islamic banking operations was found to be involved in activities that were questionable from a regulatory perspective. Consequently, shareholders of IBFIs in Africa have now adopted a cautious approach in deciding top leadership of such institutions.

“Care must be exercised to decide on the contract choice, and other factors like price volatility, customer’s credit history, and the expertise level of the bank staff must also be taken into account. If, for example, downward price volatility is the dominant factor, then one-off murabaha transaction may be a better choice. If, however, customer’s default is likely (and is still within the acceptable risk threshold), then periodic sales and ijara contracts may be more feasible. If, on the other hand, an IBFI faces excessive incidence of operational risk, simple one-off murabaha transactions may be preferred.”

In Malaysia, now there is an implicit understanding that the central bank will approve only Malay Muslims to lead Islamic banks and takaful companies as CEOs. This is, however, not so far the case when it comes to appointments in the Islamic capital market wherein Securities Commission Malaysia has yet to adopt such an implicit approach to manage risk of human capital specific to IBFIs.

In the wake of Islamic banking making its route to new markets like East Africa where local expertise in Shari’a structuring, development and audit is highly uncommon, IBFIs are expected to this specific risk, at least at the initial stage of development of IBF therein. This is a real challenge faced by IBFIs in the new jurisdictions where they face acute pressure from their conventional counterparts. Incapable, inadequately qualified or less committed human resources in such instances find it difficult to overcome competition pressure through structuring innovative products and adopting processes and procedures that favor IBF. Many industry observers believe that the credibility of

“All the Islamic banks set up in UK had CEOs who came from non-Islamic background. These CEOs were gradually replaced with Muslim CEOs who are seen more favourably by the users of Islamic financial services.”

Islamic banks with less committed workforce will adversely impact their Shari’a identity and branding.

As a general remedy to human resource-related specific risks faced by Islamic banks, HR departments of Islamic banks should make more serious efforts to raise the standards for those who are willing to join Islamic banking through recruitment, localization and continuous learning and development initiatives. In a study on top

Islamic banking brands, Meezan Bank’s employees were found to be most loyal to their bank and its brand, and there is a need to study Meezan Bank’s approach to human resource development.

Factor 4: Marketing Risk

Specific risk of marketing faced by Islamic banks is related to the possible financial and reputational suffered due to following inappropriate marketing tools in promoting Islamic financial products. This includes usage of conventional terminology in verbal and written communication.

Legal documentation and marketing material with conventional terminology might lead to shaking Shari’a Board’s confidence in the true essence of products offered by Islamic banks. Also, the personnel using conventional terminology will add doubts to the customers’ minds about Shari’a credibility of Islamic banks and the products offered by them.

“This is a real challenge faced by IBFIs in the new jurisdictions where they face acute pressure from their conventional counterparts. Incapable, inadequately qualified or less committed human resources in such instances find it difficult to overcome competition pressure through structuring innovative products and adopting processes and procedures that favor IBF.”

Similarly using inappropriate means of promoting Islamic financial products (like through music channels or cinema halls) could force Shari’a boards to take severe and unfavorable measures.

As a general remedy to risk faced by Islamic banks due to improper marketing efforts, serious thoughts should be given by the marketing departments of Islamic banks to give a positive and vibrant image of the Islamic banks, which can attract a larger market share. Moreover engaging Islamic banks in sponsoring Islamic conferences and charitable causes have proven to be a positive step to mitigate any risk of negative marketing.

Factor 5: Statutory and Legal Risk

Specific risk of statutory and legal risk faced by an IFBI is the risk of financial loss due to being subjected to certain regulatory frameworks or unfavorable decision in a court of law.

Except in a few countries (notably Malaysia), the laws of land do not recognize Shari’a principles and rulings as acceptable and applicable governing law for commercial and financial transactions.

This means that Islamic financial transactions become subject to conventional in the event of a dispute. This is particularly true when the legal documentation clearly stipulates a conventional law, e.g., the English law, as the governing law of the transaction.

Furthermore, many Islamic financial transactions are governed by complex lengthy documentation, which in many instances may not understood by judges (who are not well-versed in the Shari’a law) in the conventional courts. It may also be the case that legal documentation may have gaps and important exclusions, especially if they are prepared by law firms not fully exposed to the Shari’a requirements, or those documentation that are not properly vetted by qualified Shari’a advisors. If so, it is very likely that the transaction would be deemed null and void from a Shari’a viewpoint, in case of a dispute going into a law of court and the judge requires an independent Shari’a opinion on the transaction.

In such a case, the court will have no option but to adjudge the case from a pure conventional viewpoint. IBFIs in this circumstance are likely to incur financial losses.

“Except in a few countries (notably Malaysia), the laws of land do not recognize Shari’a principles and rulings as acceptable and applicable governing law for commercial and financial transactions. This means that Islamic financial transactions become subject to conventional in the event of a dispute. This is particularly true when the legal documentation clearly stipulates a conventional law, e.g., the English law, as the governing law of the transaction.”

Specific risk facing an IBFI in the context of regulatory framework may be understood in the context of liquidity management. In many jurisdictions, Islamic banks do not have access to Shari’a-compliant instruments to manage their liquidity requirements. While conventional banks may have access to a variety of instruments like repos and T-bills, IBFIs may have to resort to expensive bespoke arrangements for liquidity management. This is certainly a risk specific to IBFIs.

As a general remedy to the risks faced by Islamic banks due to statutory and legal factors, it should be ensured that documentation by Islamic banks’ legal departments are thorough and lean in order to cover all the Shari’a requirements to avoid being subjected to conventional rulings that are not in line with Shari’a principles. Also, Islamic banks should work more proactively on Shari’a-compliant alternatives to the existing central bank’s conventional products to avoid any financial or liquidity risk.

Conclusion

Risk management in IBFIs is a trick area, which is fast evolving with the increase in size and scope of the Islamic financial services industry. So far, however, risk managers and policy and strategy personnel of IBFIs have taken into account only secular views of risks. Consequently, the risk mitigation and management endeavor by IBFIs have resulted in bringing product development in IBF closer to the conventional practices. A proper consideration of risks specific to IBF must result in product development and structuring in favor of genuinely Shari’a-compliant products that fulfil Islamic requirements in letter and spirit.