INTRODUCTION

The past two decades have witnessed a substantial increase in the number of Islamic banks and financial institutions (IBFIs) in different parts of the world. Even if sizes of IBFIs are relatively small compared to international standards, it has to be noted that the prospects for growth and expansion in both Muslim and non-Muslim countries are strong. IBFIs include commercial, investment and offshore banks, takaful

companies and trust funds. As far as principles, Islamic banking and finance (IBF) in practice, if not in theory, has the same purpose as conventional banking and finance, i.e., profit maximization, except that it operates in accordance with the rules of Shari’a, known as fiqh al muamalat (Islamic rules on transactions). More specific principles governing IBF are the prohibition of riba (interest), trading of goods and services (rather than money lending) and possible sharing of profit and loss, wherever applicable.

It was to meet the demand for Shari’a-compliant financial services and capture the emerging market therefrom that a number of Islamic banks were set up in different parts of the world. Furthermore, conventional banks also started opening Islamic windows and Islamic units for those clients who did not want to indulge in interest-based transactions. This conviction created an increased demand for Islamic products

in the field of financing and gave birth to a market where only Islamic products are acceptable. Thus, banks working under Islamic principles and conventional banks offering Islamic financial services provide services to Muslim clients, in addition to offering a variety of products for general clientele. Despite the fact that most of IBFIs operate in the countries comprising the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), many universal banks in developed countries have begun to valve the massive demand for Islamic financial products.

The basic principles governing IBFIs have protected them from the recent global financial crisis. Indeed, it is broadly known that Islamic banks, the main part of the Islamic financial system, perform better, during the global financial crisis, than conventional banks. One key difference is that the former don’t allow investing in and financing the kind of instruments that have adversely affected their conventional competitors and triggered the global financial crisis. These instruments mainly include derivatives and toxic assets. When we compare Islamic banks to conventional ones, we are not comparing one financial institution to another as many analysts like to put it. We are rather comparing two different faunae: it is the Western spirit compared with the Eastern way of thinking. Others would rather emphatically like to describe it comparison between ethical and unethical. Greed, exploitation and abuses are the dominant factors in most financial transactions that take place under the conventional banking system. So long as commissions are received and interests are paid and the collaterals are in place, banks will lend. Reckless financial players, on the other hand, knowing the borrowed money is not theirs will borrow to the maximum. Depositors who care most about the high interest they receive will keep on depositing regardless of the behaviour of the bankers; thus, a good recipe for a crisis. They all contribute to it and they all suffer from it. While under Islamic finance, we notice that greed, exploitation, abuses are at a minimum. Reasons are attributed to the religious nature of the depositors, bankers, and investors. If the transactions are based on profit and loss sharing, direct involvement of all the parties in the transaction and their common stakes will prevent recklessness. Under such a scenario, no one has any direct or indirect interest in exploiting one another, and if they do, they all fail. In addition, IBFIs do not finance pure risky financial investments or intangible assets, and they equate the interest of the society to that of the investor.

The academics and policymakers alike point to the advantages of Islamic financial products. The first and foremost benefit of the Islamic banking model is in terms of minimization of the mismatch between short-term, on-sight demand deposits and long-term loan contracts, as Islamic investment accounts can potentially be more amenable to risk management. In addition, Islamic financial products are very attractive for customers segments that require financial services consistent with their religious beliefs.

Although it has undergone considerable developments during the past few decades, empirical evidence on the profitability, efficiency and stability of the Islamic banking sector is still in its infancy. An increasing amount of literature has compared the profitability of Islamic banks to that of conventional banks, using comparative ratio analysis. A myriad of studies have examined the comparative performance using financial ratios.

Several other studies have compared the efficiency of Islamic banks (both full-fledged banks and Islamic windows) and conventional banks in the context of market structure (competitive or otherwise). A number of key indicators

(traditional concentration measures, the PR statistic, and the Learner index) have been used in this context.

Some studies have examined bank-specific factors of profitability (e.g., size, revenue growth, risk, and control of expenses), while cross-country investigations have considered external factors (e.g. inflation, concentration, and GDP growth), in addition to a few internal factors of profitability.

Admittedly, the results from many of these previous studies comparing the performances of Islamic and conventional banks are unsatisfactory. There are several reasons for that.

First, a large proportion of the studies is based on small samples (particularly of Islamic banks).

Second, where sample sizes are large, the data have often been collected across a variety of countries with very different economic size.

Third, the significance of the differences in performance between the two types of banking is often not tested. Studies have generally employed few financial ratios – mainly return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE) – to examine the performance of the banks.

Fourth, these studies do not provide clear answers whether and how the profitability, cost efficiency and stability differ between conventional and Islamic banks.

This ambiguity is exacerbated by lack of clarity whether the products of Islamic banks follow Shari’a in form or in content.

This edition of GIFR includes a recent study on the profitability, efficiency and stability of Islamic banking in a brief chapter (see Chapter 13).

BOX 1: POTENTIAL AND ACTUAL SIZE OF THE GLOBAL ISLAMIC FINANCIAL SERVICES INDUSTRY

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

| Potential size of the global Islamic financial servicesindustry (US$ trillion) | 4.0 | 4.4 | 4.84 | 5.324 | 5.865 | 6.451 |

| Actual size of the global Islamic financial servicesindustry (US$ trillion) | 1.036 | 1.139 | 1.357 | 1.631 | 1.813 | 1.984 |

| Size gap (US$ trillion) | 2.964 | 3.261 | 3.483 | 3.693 | 4.043 | 4.47 |

| Growth in actual size of the global Islamic financialservices industry (%) | 26 | 9.9 | 19.1 | 20.2 | 12.3 | 9.3 |

| Average growth rate between 2009-2014 (%) | 16.1 | |||||

| Catch-up period – based on 10% growth in potential size and 20% growth in actual size (years) | 13.5 | |||||

| Catch-up period – based on 10% growth in potential size and 16.1% growth in actual size (years) | 22 |

The potential Size of the global Islamic financial services industry can be defined as the assets under management (AUM) of the institutions offering Islamic financial services to all those who would like to have access to such services, and to all those who would like to use Islamic financial services but have excluded themselves voluntarily from the financial services market because such services are not available. The demand for Islamic financial services amongst the Muslims – individuals and the business owned by Muslims – is estimated to be over 90% and 70%, respectively.

This definition implies that:

Î The suppliers of financial services do not meet the full demand for Islamic financial services – purely unmet demand;

Î On the demand side, not all those who demand Islamic financial services actually have access to such services and financial products – involuntary financial exclusion; and

Î Also, there are certain people who otherwise have access to Islamic financial services but are not entirely satisfied with them either on religious grounds or because of business features of such products voluntary financial exclusion.

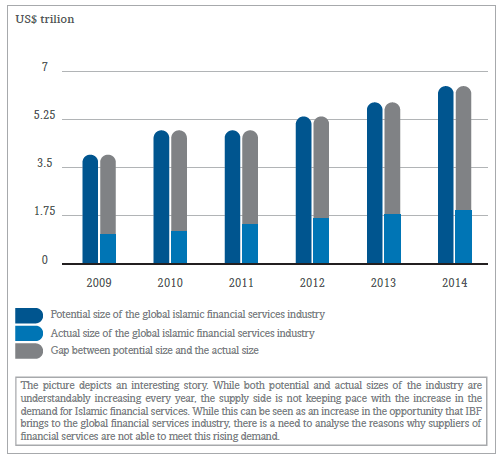

Potential size of Islamic financial services has grown from US$4 trillion in 2009 to US$6.451 in 2014, with an annual growth rate of 10%. Actual size of the global Islamic financial services industry reached US$1.984 at the end of 2014, from slightly over US$1 trillion in 2009, with an average annual growth rate of just over 16% (see Diagram B1.1).

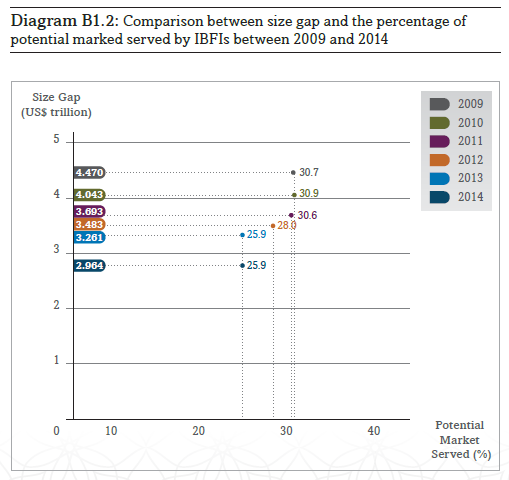

Size gap, i.e., the difference between the potential and actual size, has widened, implying that the industry has failed to cope with the growing demand for Islamic financial services (see Diagram B1.2). The question then arises as to why the gap has increased despite growing awareness of IBF in the countries where it has strong foothold and in a number of other

Diagram B1.1: Gap between potential and actual sizes of the Islamic Financial Services Industry

countries where it has emerged as a relatively new phenomenon. There are a number of reasons:

The institutional response has been slow: Institutions including banks and financial institutions, regulators, and other stakeholders like service providers have faced a challenging task to adjust their businesses and to develop a comprehensive framework for the development of IBF. This has in particular been true in recent times in a number of countries where interest in IBF has just started to emerge.

Most of the unmet demand relates to the financially excluded: As tapping the financially excluded has been challenging even for conventional banks and financial institutions, IBFIs have found it even more difficult to reach out to this segment of the market.

Purely statistical reasons: The size gap in absolute number is in billions and any percentage changes in it are expected to be big in size; on the other hand the percentage market (both actual and potential) served is a relatively small number and any changes in them are expected to be smaller than the size gap.

A speculative explanation of the size gap may very well be non-synchronization of expectations of the potential customers of Islamic financial services and the products offered by Islamic banks and financial institutions (IBFIs).

IBF IN fl014

A hallmark of IBF in 2014 has been the issuance of sovereign sukuk by United Kingdom, Luxembourg, South Africa and Hong Kong. For all practical purposes, the year has proven to be a period that may be considered as a start of maturity and consolidation for the industry. While no mega transactions came to fruition during the reported period, the industry continued to grow steadily. One must, however, notice that the earlier growth pattern is giving way to a slower and steadier pace (see Box 1). It is imperative to study this phenomenon to get implications for further growth in the global industry. This issue has been dealt with in some detail in Chapter 6.

According to a survey commissioned by Finance Accreditation Agency (FAA) in February 2014, talent shortage is a major hindrance in further development of the industry. While talent shortage may have contributed to the slowing growth, the problem is nevertheless more accentuated with respect to the top management of the institutions offering Islamic financial services. Even after forty years of existence, IBF has failed to develop leadership that has global recognition, respect and relevance. This is primarily because IBF has so far developed itself as a niche embedded in the global financial services industry. Its truly independent identity has yet to emerge, owing primarily to a lack of a distinct economic value proposition that is otherwise needed but badly missing.

There are four possible levels of leadership that must be developed to enhance the global role of IBF:

- Country leadership in the form of an unambiguous commitment and support;

- Institutional leadership by large institutions offering Islamic financial services;

- Product-level leadership by way of developing “flagship” Islamic financial products with a global appeal and outreach; and

- Individual leadership spearheaded by the “rock-star” IBF

This report analyses the issues pertaining to leadership in IBF in detail (see Section 3).

This chapter provides an overview of the global Islamic financial services industry, with a focus on the size and growth.

SIZE OF THE GLOBAL ISLAMIC FINANCIAL SERVICES INDUSTRY

Edbiz Consulting estimates that the size of the global Islamic financial services industry reached the mark of US$1.984 trillion at the end of 2014.

Saudi Arabia and Malaysia remain central to the growth story of IBF on a global level. With Islamic financial assets of US$339 and US$249 billion respectively, they are the two leading players in the global Islamic financial services industry. There is further coverage of these countries including another 32 in chapter 3.

Suffice to say, however, that any financial institutions contemplating to enter IBF must consider either to base their business therein or to create credible linkages with the IBFIs in these jurisdictions.

Figure 1 summarizes the growth of IBF between 2007 and 2014. It is interesting, if not alarming, to note that the global Islamic financial services industry has witnessed slow down for the second consecutive year – from the high annual growth rate of 20.2% in 2012 to 12.3% in 2013 and a further lower growth rate of 9.3% in 2014. This slow down in growth is further referred in Chapter 6 on need for a collective global strategy for growth and competition in the context of IBF.

Banks continue to dominate in terms of assets under management (AUM) of IBFIs, with 75% of the global Islamic financial assets held by Islamic banks and conventional banks in their Islamic window operations. The second largest sector in terms of AUM is sukuk, which comprises 15% of the global Islamic financial services industry. Islamic investment funds have yet to see any significant growth and so is the case for takaful and the emerging business of Islamic microfinance.

| COUNTRIES | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | FO |

| Iran | 235 | 293 | 369 | 406 | 413 | 416 | 480 | 530 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 92 | 128 | 161 | 177 | 205 | 215 | 270 | 339 | |

| Malaysia | 67 | 87 | 109 | 120 | 131 | 155 | 200 | 249 | |

| UAE | 49 | 84 | 106 | 116 | 118 | 120 | 123 | 144 | |

| Kuwait | 63 | 68 | 85 | 94 | 95 | 103 | 105 | 107 | |

| Bahrain | 17 | 21 | 18 | 18 | 20 | 21 | 25 | 27 | |

| Qatar | 21 | 28 | 35 | 38 | 47 | 68 | 70 | 111 | |

| Turkey | 16 | 18 | 22 | 25 | 35 | 41 | 43 | 69 | |

| UK | 18 | 19 | 24 | 27 | 33 | 37 | 40 | 43 | |

| Indonesia | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 22 | 25 | 49 | |

| Bangladesh | 6 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 13 | 17 | 19 | 21 | |

| Egypt | 6 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 12 | 19 | 19 | 20 | |

| Saudan | 5 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

| Pakistan | 6 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 16 | |

| Jordan | 3 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 14 | |

| Iraq | —- | 4 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 13 | |

| Brunei Darussalam | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 12 | |

| Syria | 1 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Other Countries | 27 | 32 | 49 | 56 | 170 | 333 | 327 | 200 | |

| Total | 638 | 823 | 1,034 | 1,138 | 1,357 | 1,633 | 1,813 | 1,984 | 1 |

Table 1: Size of the Global Islamic Financial Services Industry

Note on IRAN

As Table 1 shows, bulk of Islamic financial assets is located in Iran, which could mislead the size of the industry. Despite claiming to have the largest concentration of Islamic financial assets, Iran has not played any significant role in the global Islamic financial services industry, which is partially explained by the economic sanctions the country has for long been facing. Another reason for lack of Iran’s leadership role has something to do with the approach it has taken in defining IBF and operationalizing it domestically. In addition, there are obvious political reasons, as Iran has failed to engage itself with other significant players in the Islamic financial services industry, most notably Saudi Arabia and Malaysia. With the on-going political conflict in the Middle East, Iran’s isolation in IBF is expected to continue.

It is interesting to note that all the three countries – Pakistan, Iran and Sudan – that were once focus of Islamic banking (especially in the 1980s and early 1990s) have lost their leadership stature in favor of Malaysia and the countries in the GCC region. All the three countries have suffered in somewhat similar ways of political instability in their respective jurisdictions, but Iran and Sudan have suffered more.

Given that Iran’s Islamic financial assets are the largest in terms of volume – US$530 billion at the end of 2014 – and are in fact nearly one-fourth of the global Islamic financial assets, it is absolutely imperative to engage Iran in a more active way in IBF.

Once the economic sanctions are lifted, Islamic banking in Iran will be the direct beneficiary, as Iran will have to open up its economy to foreign investors and the banks will be expected to play their role in advising on financial transactions and structuring them. One area of growth will be sukuk. One must hope that the government of Iran will be interested in adopting a sukuk programme to meet its public sector borrowing requirements.