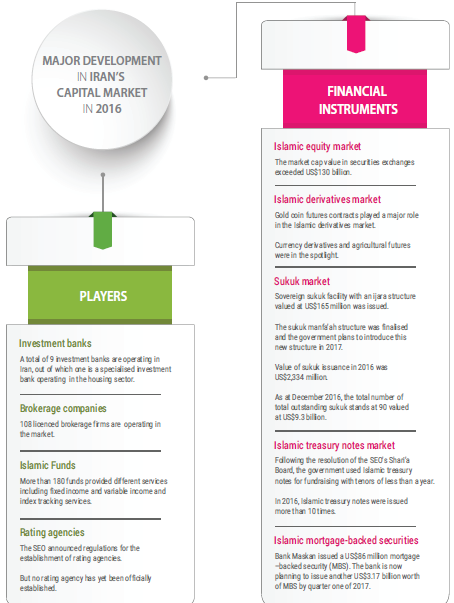

Islamic banking and finance in Iran took a great leap when the Islamic Revolution in 1979 broke down any barriers for the rapid process of Islamisation. What began as a popular democratic movement ended up with the establishment of an Islamic state known as the Islamic Republic of Iran. Iran’s banking system has been fully Islamic since 1983, and its banking assets account for around 40% of the global Islamic banking industry, making it the largest Islamic financial system in the world.

With a population of about 80 million, Iran is the second largest economy in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region after Saudi Arabia, with an estimated Gross Domestic.

Product (GDP) of US$393.7 billion in 2015 according to the World Bank. While the country’s economy is considered to be completely Islamic, various fundamental differences in Shari’a interpretation across its banking sector, capital markets and investment mandates could lead to challenges for firms seeking to enter the market.

Islamisation of the Banking System

With the culmination of the Islamic Revolution, the government set out to transform the country’s economic system into a fully-Islamised banking system based on Shari’a principles. This saw 3 major phases in the process of Islamisation of the banking system. In the first phase, from 1979 to 1982, the banking system was nationalized, restructured and reorganized in order to remove any weaknesses of the existing banking system. With the ratification of the Law on Nationalization of Banks in June 1979, all private banks in Iran were nationalized including 14 Iranian banks and 13 foreign banks. Foreign banks were not allowed to establish a branch bank in Iran. They were only permitted to establish representative offices. On 25th June of the same year, 15 privately owned insurance companies were nationalized.

In 1980, 27 domestic banks were consolidated into a central bank and 9 other banks (6 commercial banks and 3 specialized banks) in which banks with similar activities were merged. Commercial banks included Mellat Bank, Melli Bank, Saderat Bank, Tejarat Bank, Bank Rafah Kargaran and Sepah Bank whilst specialized banks were Keshavarzi Bank, Maskan Bank and Sanat o Madan Bank. However, existing banks – Bank Melli, Bank Sepah, Bank Saderat and Bank Rafah Kargaran, continued to operate under the government management. In the same year, the Money and Credit Council of Bank Markazi Iran (Central Bank of the Islamic Republic of Iran or CBI) reduced interest rate charged by commercial banks against borrowers and those paid to depositors. During this initial phase of Islamisation of the banking system, banks revised their operations and avoided using fixed interest rate in their deposit-taking and lending operations The period from 1983 to 1986 marked the second phase. During this period, the structure of an Islamic banking system was put in place with the passing of the Usury Free Banking Law on September 1, 1983; which came into effect in March, 1984. The enactment of this law opened a new horizon in the banking practices in Iran. The law banned the payment of interest on all lending and borrowing activities. Hence, interest on loans was replaced by a 4% service charge while interest on deposit was replaced with profit rates of between 4-8%, depending on the type of economic activity. Interest on deposits were converted into a guaranteed minimum profit of 7% for short-term savings and 8.5% for long-term savings accounts. The law also described 14 types of operations applicable to assets and liabilities. However, an exception to this prohibition of interest is provided by the Regulations on Monetary and Banking Operations in Free Trade – Industrial Zone, which states that foreign currency transactions conducted from within a free zone are exempted from implementing the Islamic banking system. It remains unclear, however, whether this exemption is consistently applied in practice.

All banks were given a deadline of one year to convert their deposits in line with Islamic law and 3 years to fully convert their operations. However, an exception was made for the ordinary transactions of the central bank with the government, government institutions, public enterprises, as well as banks, as long as these institutions use their own resources. With the legislation of the Usury Free Banking Law, banks shifted their lending operations towards participatory modes of contracts and in the consequent years, they fully transformed their operations from that of a fixed interest rate to be based on profit rate. The third phase began in 1986 and continues until today. During this phase, Iran experienced a reconstruction of the financial system, concentrating on reforming the regulatory conditions through the implementation of a number of Five-Year Economic Development Plans.

Different Jurisprudential Approach

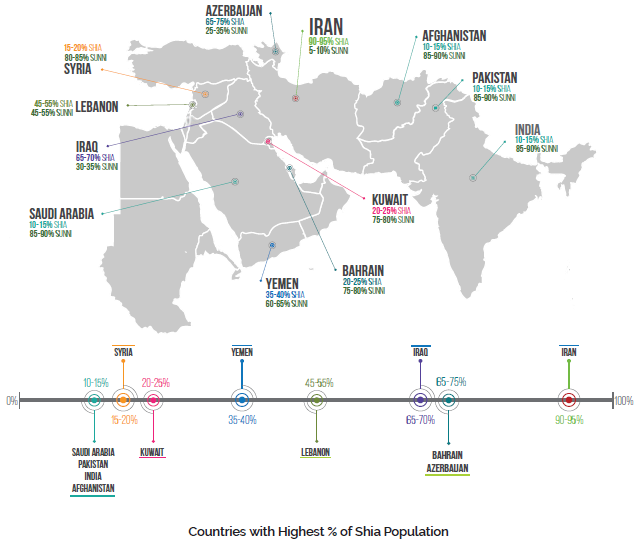

Iran is home to the largest Shia community, with Shiites representing 95% of the country’s population. Shiites are estimated to make up about 15% of the world’s Muslim population, the remainder being Sunnis (Figure 1). Although both sects share common religious beliefs: the five pillars of Islam, the Quran and Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) being the last messenger of God; Shia has a different jurisprudential approach than Sunni when it comes to interpretation of the hadiths and Shari’a law. For example, qiyas or analogical deduction is a fundamental source of Shari’a after the Quran and Hadith. In case of the lack of direct text, from the Quran or Hadith, on any contemporary issue, making a judgment based on analogy is permissible by Shari’a.

However, the Shia Muslims do not view qiyas as a fourth source of Shari’a law. In fact, the Jafari School of Thought, which is the primary school of Shiites, rejects the usage of qiyas altogether, replacing it with aql or human reason. Shia jurists also reject consensus or ijma (consensus among Muslim scholars) as not having any particular value but view it as a means through which the opinion of the Prophet or the Imams may be discovered.

Another difference is Shari’a interpretation on the ability to sell debt at a discount, which is allowable under Shia rules but not Sunni. Dominant Shari’a opinion (which is Sunni in this case) prohibits selling debt for a price other than its face value. This prohibition covers both discounts and premiums in the sale and purchase of debt. Many resolutions have been issued on the prohibition of this process. One of them is Resolution No. 64 (7/2) of the International Islamic Fiqh Academy, which stated that the discount of commercial papers is not permissible in Shari’a because it amounts to a transaction involving riba al nasi’ah (interest on delayed repayment), which is prohibited.

In addition, according to Shia interpretation, conventional insurance is not viewed as non-Shari’a-compliant as the Shia school of thought defines gharar differently from that of Sunnis’. The Shiites view gharar as a concept on a continuum ranging anywhere between ‘gharar yasir’ or tolerable/minor uncertainty and ‘gharar fahish’ or excessive uncertainty and the legitimacy of a business transaction is decided depending on the degree of uncertainty. This reasoning is acceptable to the Shia Muslims as it is in line with the Shia tradition of ijtihad, meaning independent reasoning to arrive at religious edicts and conclusions. This explains why there is no takaful industry in Iran. All the examples provided show that whilst Iran’s entire legal system is Islamic based, differences in Shia interpretation implies that the Iranian financial system operates under very different rules in comparison to other countries where Islamic banking and finance is being implemented. This could pose a challenge for Iran in its efforts to integrate into the global Islamic finance industry and could be a stumbling block to its entry on the international stage post sanctions.

Sanctions on Iran

The US has been imposing successive economic sanctions against Iran in one form or another since the 1979 Iranian Revolution. In 1995, the US expanded sanctions to include non-Iranian firms dealing with the Iranian government, thus effectively preventing any company from engaging with Iran if they wish to do business with or in the US. The following year, the US Congress passed a law requiring the US government to impose sanctions on foreign firms investing more than US$20 million a year in Iran’s energy sector. In subsequent years, the US sanctions were primarily aimed at Iran’s financial sector and the oil and petrochemical sector.

DISTRIBUTION OF SUNNI AND SHIA MUSLIM POPULATION

IN THE MIDDLE EAST

In 2006, the United Nations (UN), amidst concerns about Iran’s uranium enrichment programme, passed Resolution 1696 and imposed sanctions on the country after Tehran refused to suspend the programme. Sanctions were imposed on Iran’s trade in nuclear-related materials and technology. Since then the UN have been progressively imposing punitive sanctions including travel bans on individuals, freezing offshore Iranian assets of key individuals and companies, imposing a ban on the supply of heavy weaponry a nuclear-related technology to Iran, and blocking arms exports.

In addition to implementing UN sanctions, EU imposed its own sanctions on Iran covering both economic and financial sanctions. Among them were restrictions on trade in equipment which could be used for uranium enrichment, asset freeze on a list of individuals and organizations that the EU believed were helping advance the nuclear programme including a ban on them from entering the EU, a ban on any transactions with Iranian banks and financial institutions and a ban on the import, purchase and transport of Iranian crude oil and natural gas (the EU had previously accounted for 20% of Iran’s oil exports). In 2012, Iranian banks were disconnected from the global transaction network SWIFT, which effectively meant that Iranian banks were cut-off from the global financial system.

In January 2016, Iran received extensive economic and financial sanctions relief from UN and the EU following confirmation from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) that Iran had met its obligations under the nuclear deal agreed on 14th July 2015. This meant that Iran was now able to trade more freely globally. Following the lifting of sanctions on Tehran, SWIFT has reconnected a number of Iranian banks to its system, allowing them to resume cross-border transactions with foreign banks.

Development of Islamic Banking and Finance in Iran

Since the Islamisation of the country’s economic system in 1979 and the passing of the Usury Free Banking Law 1983, all banks in Iran can only engage in interest-free Islamic transactions and such transactions are performed through Islamic contracts, such as mozarebe (profit-loss sharing), foroush aghsati (instalment sale), joale (fee-based transactions), salaf (futures), and gharz al hazaneh or qard hassan (benevolent loan). Under the legal framework for Islamic banking, four types of deposits are allowed to be offered by banks: demand deposits that are interest-free “loans” to the bank; savings accounts (gharz al hazaneh or GAH); term deposits/investment accounts in which depositors share in the general profits of the banks; and since 2011, special-purpose investment accounts in which the investor/depositor restricts the use of funds to designated projects where the bank is also an equity partner (generally used by specialized banks).

Savings deposits receive some remuneration in the form of “bonuses” in cash or in kind through random drawings. Here, banks are required to distribute 2.5% of GAH deposits per year through random drawings. The provisional remuneration of term deposits, on the other hand, is set by the Money and Credit Council (MCC) each year with a view to ensuring reasonable funding costs. The MCC is the highest banking policy-making body of CBI and decides on the country’s macro-finance and banking policy including determining the regulations pertaining to determination of profit rate or expected rate of return on banking facilities and the minimum and maximum profit rate or expected rate of return. The Islamic credit contracts take two forms — participatory and non-participatory facilities. Under the participatory contracts, banks will share profits on the investment being financed. Non-participatory contracts, on the other hand, are similar to leasing structures, where the bank’s remuneration is a mark-up on the acquisition value of the goods being financed.

In early 2009, the juridical council was formed at CBI. This council, which consists of juridical, economic and banking experts, discusses newly proposed Islamic financial instruments and resolves any Shari’a concerns that may arise. Although the council has no formal and legal position, over the years it has prepared numerous approvals for various issues including formulating Shari’a instructions for issuing participation securities, formulating Shari’a instructions for issuing certificate of deposit currency, formulating Shari’a instructions for using future currency transactions to cover risk, planning for the approval of Shari’a-compliant procedures for other types of sukuk, devising inter-bank transaction tools in usury-free banking, formulating Shari’a instructions for repurchase agreement or repo in usury free banking and formulating Shari’a instructions for different applications of purchasing loan.

Due to several weaknesses inherent in the Usury Free Banking Law, the conversion to

Islamic modes has been much slower on the asset side than on the deposit side. One reason cited for this slow pace is that there is inadequate supply of personnel trained in long-term financing.

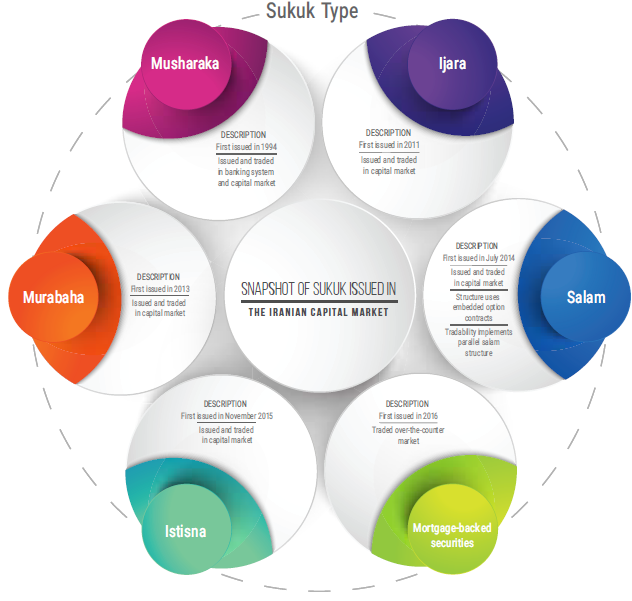

Sukuk Market

Sukuk were first introduced in Iran in 1994 in the form of “participation bonds” (musharaka sukuk) issued by the municipality of Tehran to finance Navvab project, which was valued at US$28 million. However, since there were no rules and regulations pertaining to sukuk issuance at that time, the CBI published “Regulations Governing Issuing Musharakah Sukuk” in June 1994, which was ratified by the Money and Credit Council. This new law became the legal base for the issuance of the musharaka sukuk in replaced of the Regulations on Issuing of Bonds.

After the first successful issuance, sukuk became a popular method to raise funds by governments, state-owned companies and private companies. These participation bonds are redeemable on demand and at face value from the issuing agent. As such they were deemed as unsuitable for secondary trading. As a result of this, issuances had been small – less than 1% of GDP between 2009 and 2010, and registered at 4% in 2011.

In 1997, the Regulations Governing the Issuing of Musharakah Sukuk, including 13 articles, were ratified by parliament to take into account deficiencies concerning the present regulations of the time. These deficiencies included lack of coordination with other rules and regulations, rendering of powers and duties of the CBI and lack of certain regulations on converting these securities to stocks. The Law and the Bylaw were also enacted specifying among other things the framework for the issuers’ guarantees, duties of respective authorities and on convertible musharaka sukuk. The new law also saw the CBI as the sole authority to issue permit for sukuk issuances in Iran. However, following the approval of the Securities Market Act, ratified in 2005, this responsibility was rendered to the Securities and Exchange Organisation (SEO).

In 2008, standards governing financial instruments of ijara securities were approved by the Securities and Exchange High Council. However, this was not implemented due to tax ambiguity and some executive concerns. The regulation on ijara sukuk was only finalized in 2010 and later revised in 2014. Nonetheless, the main factor that facilitated the issuance of ijara sukuk was The Law for Development of New Financial Instruments and Institutions (Articles 11 and 12), which was ratified in 2009. Under this law, Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) were recognized as one of the financial institutions under the Securities Market Act. Article 11 outlines tax exemptions of SPV where it shall be exempted from paying any tax. The article further spells out tax advantage to investors where “no tax whatsoever shall be claimed for the transfer, issuance and redemption of the foregoing securities”. Article 12, on the other hand, states that proceeds gained from selling assets to the SPV shall be exempted from tax and no tax and charges whatsoever shall be levied on the transfer of such securities.

With the regulations in placed, the first sukuk was issued in March 2011 by Mahan Airlines, valued at US$28 million with a 4-year maturity, followed by Saman Bank and Omid Investment Company with an issuance of US$85 million (in June 2011) and US$103 million (in August 2011), respectively. Mahan Airlines issued another ijara sukuk in August of the same year valued at US$86 million.

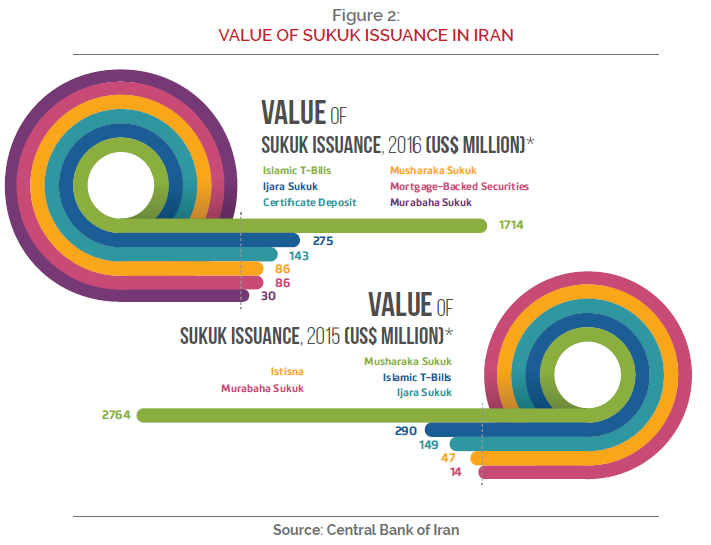

In 2012, SEO adopted The Regulation Governing the Issue of Murabaha Sukuk, thus paving the way for a new type of sukuk issuance in the country. The first murabaha sukuk was issued to finance Butan Company in 2013. A year later, the Iranian capital market issued the fourth type of sukuk – salam sukuk, which was used primarily to finance oil exploration and deployment projects by the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC). The model of trading was approved by Shari’a Board of SEO and the first and second phase of issuance was launched on the Iran Energy Exchange. This was thought to be the region’s first Islamic instrument in the Energy Market. From July 2014 until December 2016, the value of outstanding salam sukuk was over US$800 million, accounting for around 9% of total sukuk outstanding in Iran’s capital market as at the end of 2016.11 Istisna sukuk first made its debut in Iran in 2015. Novin Investment Bank subscribed the first istisna sukuk in the Iranian capital market on behalf of Tose’e Melli Mining and Industries Company for raising US$45.8 million at market exchange rate. This was to finance the completion two iron ore concentrate and pellet plants located in the city of Sangan, northeastern Khorasan Razavi Province.

The Iranian’s capital market has a deep market for musharaka sukuk but it is very small for ijara, murabaha, salam, istisna and mortgage-backed securities. The SEO has since taken serious steps to make Shari’a-compliant financial instruments more attractive to foreign investors with sukuk being the preferred instruments to serve this purpose. One important modification in the sukuk market in 2015 was the new procedure for subscription, which was based on investor valuation in IPOs. In 2016, Bank Maskan issued a US$86 million mortgage–backed security (MBS). This marked another effort by SEO to introduce regulated debt instruments in the country. The bank is now planning to issue another US$3.17 billion worth of MBS by quarter one of 2017. In September 2015, the first treasury bills after the 1979 Islamic revolution were issued with a face value US$33.16 per each bill and a maturity of 5.5 months. The bills are traded on Farabourse.

With the introduction of rules and regulations for the purchase of MBS, the SEO hoped to revive the mortgage market. In 2015, the SEO announced that it was going to use istisna sukuk more widely as a financial tool. In the same year, Iran’s Ministry of Finance issued US$165 million ijara sukuk with a 4-year maturity. The sukuk was oversubscribed on the over-the-counter securities market of the Farabourse. This was the first ijara sukuk to be issued by the Iranian government. Previously, the government had used musharaka sukuk to meet its financing needs. As shown in Figure 2, the value of sukuk issuance was US$3,264 million in 2015 and US$2,334 million in 2016. As at December 2016, the total number of total outstanding sukuk stands at 90 valued at US$9.3 billion. However, the sukuk market in Iran faced several challenges. The most critical being that the Iranian financial law does not allow government sukuk to be traded in foreign currencies. This poses a major obstacle in the development of the sukuk market as Iran integrates into the global Islamic finance industry.

Banking Sector in Iran

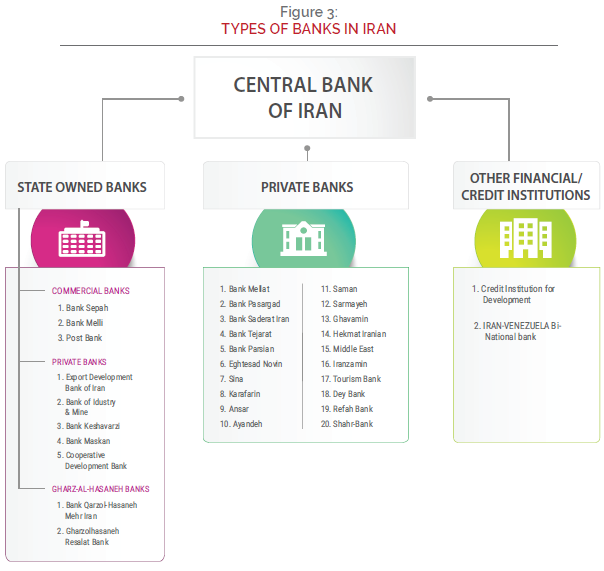

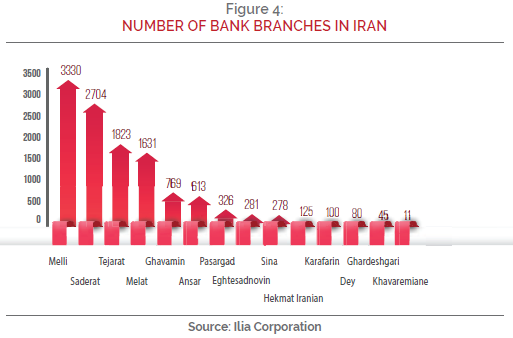

There are 3 types of banks in Iran – state-owned banks, private banks and other financial institutions. All of these banks are governed by the central bank, Bank Markazi. As shown in the Figure 3, state-owned banks consist of commercial banks, private banks and Gharz-alhasaneh banks. To date, there are 30 banks and 2 financial/credit institutions operating in Iran. Out of this, 20 are listed on the Tehran Stock Exchange. Although Iran was cut off from the global banking sector due to sanctions imposed, the domestic banking sector in Iran has overcompensated and is effectively overbanked. Iran has over 15,000 bank branches with Bank Melli, Bank Saderat, Bank Mellat and Bank Tejarat having the largest number of branches across the country (Figure 4).

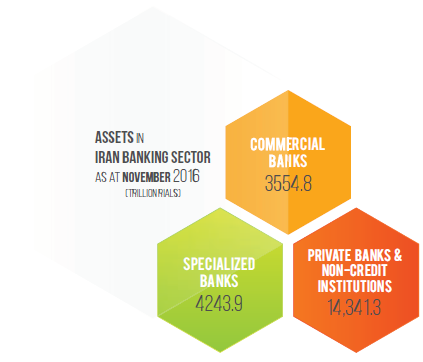

Iran’s financial system has undergone major transformation with major privatization and modernization of the country’s banking sector are underway. The banking system was previously dominated by state-owned banks including commercial banks, private banks and specialised banks or gharz-al-hasaneh banks, which jointly hold about 85% of the Iranian banking sector. However, following the privatisation of large public commercial banks in 2008-09, private bank assets have become the largest in the system. As a result, private bank assets grew from 13% in 2007 to 65% in 2016 due to the licensing of private banks. The seven largest private banks are listed on the stock exchange and are counted among the most actively traded stocks.

A New Era for Islamic Finance in Iran

Iran is poised to re-emerge as a powerhouse in the Middle East. Two important events may present the much needed boost for Iran to change its current status quo – the lifting of international economic and financial sanctions and the chairmanship of the Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB) in 2017. Iran is already a leader in the global Islamic finance industry in terms of the size of Islamic banking assets. Iran’s banking system, which has been secluded from the rest of the global financial system in the past as the direct result of financial sanctions imposed, is not fully aligned with other important Islamic finance jurisdictions.

However, with the gradual opening of Iran’s economy to the world after the lifting of international sanctions, a large number of sukuk and other Islamic securities from Iran are expected over the next few years as Iranian companies and state organizations would likely have to finance a significant amount of infrastructure development projects and power plants through sukuk issuance. Investments in key economic sectors have also declined due to the lack of available financing sources as sanctions cut Iran’s access to the international capital markets and prohibited foreign investments in most of its economic sectors. A renewed focus on Islamic project finance is also expected to boost the global Islamic finance industry.

The appointment of Iran’s central bank governor as chairman of IFSB is seen as a major boost to Iran’s bid to reintegrate into the international finance system and could help Iran fine-tune its finance practices with those in other Islamic financial centers across Asia and the Middle East, particularly the GCC. The IFSB is one of the main bodies for Islamic finance that sets international standards and prudential guidelines including governance, capital adequacy and liquidity risk management.