The introduction of internet, e-commerce, mobile network and smart devices has greatly contributed in changing the shape of monetary and financial services in the contemporary financial architecture. However, the inception of Bitcoin along with the blockchain technology has been among the greatest influencers and strongest catalysts for disruption. Although, Bitcoin and blockchain technology are still in their infancy stages, experts have already regarded their impact and effect as the beginning of a new technological revolution, particularly relevant to the financial services sector.

Following the global financial crisis in 2008, Satoshi Nakamoto introduced the idea of digital peer-to-peer (P2P) payment system in the form of Bitcoin and suggested reducing the intermediary role of financial institutions in financial transactions. The system was introduced as an alternative to building trust among the parties of a transaction at a distributed network, instead of having a third party to establish it while maintaining their anonymity (Nakamoto, 2008). Immediately after initiating the idea, Satoshi Nakamoto also developed the system and uploaded it as an open-source programme in 2009.

Within a period of less than a decade, the crypto-assets industry is already a multi-billion dollars industry. While the industry has caught up between the reality and opportunities as well as the hype and controversies, Shari’a compliance of this phenomenon remains a major issue, particularly for the Islamic finance industry. This challenge has been posed to the Shari’a scholars and Islamic finance experts for their response. But due to the dearth of quality research work and lack of data and literature, many misunderstandings and misconceptions have emerged surrounding the topic of crypto-assets and their Shari’a-compliance. Those misconceptions have greatly affected the Shari’a opinions regarding this phenomenon and hence, causing huge variances in issuing Shari’a ruling for it.

A balanced and comprehensive Islamic legal characterization of crypto-assets and their criteria of Shari’a compliance based on appreciating the underlying technology, processes, systems, and mechanisms have been warranted for quite a while. The questions like what is the Islamic legal status of crypto-assets; what is the criteria of Shari’a-compliance of such asset class; is creating, using, investing or holding crypto-assets Shari’a-compliant; and many similar challenging questions have been posed to the Shari’a scholars.

With the above backdrop, this chapter offers an insightful Islamic legal analysis of crypto-assets based on their vigorous understanding and proper categorization. It aims to offer a reference point for those who are interested in understanding the Shari’a viewpoint on crypto-assets and to discuss how Shari’a scholars should approach this intricate, yet crucial issue. Before delving into the main discussion, it is crucial to mention at this point that the term ‘cryptocurrency’ is a misnomer and widely misunderstood. It would be made clearer in the later discussion that neither all types of crypto-assets are ‘currencies’, nor ‘cryptocurrencies’ are the only type of crypto-assets.

Actually, cryptocurrencies are a subset of crypto-assets, while there are many other types of crypto-assets. The reason for the popularity of the term ‘cryptocurrency’ for all types of crypto-assets is that the first crypto-asset, Bitcoin, and other early-stage crypto-assets the likes of Namecoin, Litecoin, Peercoin, etc. were created as currency-tokens or coins. However, in this chapter, the term ‘cryptocurrency’ is intentionally avoided to circumvent that misunderstanding and save the reader from confusion. That is why, the term ‘crypto-assets’ is preferred and used throughout the chapter, which is technically and logically more appropriate and less confusing for such type of asset class.

Crypto-Assets Explained

It is not surprising not to find any suitable definition of crypto-assets, as they have not been understood, or at least not discussed in the existing literature with comprehensiveness and in-depth understanding. The current literature indeed defines the term ‘cryptocurrency’, but most of the definitions and explanations mentioned in that literature confine the discussion within the context of ‘currency’ or ‘money’. For instance, Investopedia.com (2018) provides the definition as:

‘A cryptocurrency is a digital or virtual currency that uses cryptography for security.’ (Investopedia.com, 2018)

As mentioned earlier, the crypto-asset is a wider concept than cryptocurrencies. That is why, such definition cannot be used to define crypto-assets. Accordingly, an appropriate definition can be given as:

“A crypto-asset is a digital representation of value that uses crypto-graphic encryption techniques.”

From the definition, three main points need an explanation to have a better understanding of crypto-assets. This understanding subsequently contributes to the Islamic legal characterization (takyif fiqhi) of such asset class. The first important term in the definition is ‘digital’. It means crypto-assets do not exist physically. They are a virtual or intangible form of assets. However, being digital does not mean that they are imaginary or non-existent. They are specific numbers created by a digital computer programme or code as a result of solving a particular mathematical problem. The mathematical problem is solved by known algorithms, which are run on computers or certain electronic devices built for such purpose called ‘mining devices’ or ‘miners’.

The process of solving the mathematical problem is called ‘mining’, which can be done either by contributing computing power as in proof-of-work (POW) system, by having a certain stake in the system as in a proof-of-stake (POS) system, or by any other criteria defined by the creator of any specific crypto-asset system in its protocols. The number generated by the system is actually the digital coin or token, which resides and is stored in the blockchain system itself. This number or digital coin/token is uniquely identifiable and cannot be duplicated or counterfeited. It can be transferred from one electronic wallet to another wallet on the blockchain; which means it can be owned, traded, or transferred from one party to another. This transfer can be easily traceable too.

The second term is ‘cryptographic encryption’. This encryption technique is used not only to maintain the anonymity of the transacting parties while performing transactions, but also to ensure that the network remains highly secured and hard to be forged. It is almost impossible to create a digital token on a blockchain system without following the protocols specified by the creator of that particular blockchain system. The third term is ‘value’ which is pivotal to the concept of crypto-assets. The question arises that since crypto-assets represent a certain value, where do they derive this value from? There can be many sources for deriving the value of crypto-assets. Accordingly, crypto-assets can be categorized based on their sources of value and features. Therefore, in the next section, the categorization of crypto-assets based on their sources of value is discussed.

Taxonomy of Crypto-Assets

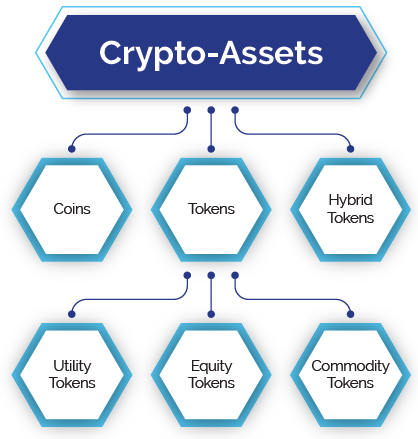

A crypto-asset is represented in the form of units, which can be categorized as ‘coins’, ‘tokens’ or ‘hybrid’. Tokens can be further divided into (1) utility tokens; (2) equity tokens; and (3) commodity tokens.

• Coins

Blockchains have their own native digital asset, which is represented in terms of a unit. That unit is called a ‘coin’. A coin can only serve two purposes: (1) to pay the transaction fee on its native blockchain; and (2) to transfer value among different parties. The value of a crypto-asset can be based on people’s trust and belief in the blockchain system, without the token having any intrinsic utility. A specific group of people, or even ordinary people who are interested in such digital coins, believe that such coins have value due to demand, supply and other market forces. The value of such type of coins also depends on their acceptability and usage as transfer of value. Normally, coins can be used only as a store of value and transfer of value; hence they can also be used as a medium of exchange. Due to this reason, they can be called digital currency. This is exactly the case of Bitcoin. The only intrinsic utility of Bitcoin is to digitally store and transfer value. But it has gained the trust of the people, and subsequently, its acceptability has widened (Kelleher, 2018).

Moreover, a government can also transform its national currency into digital coins. In this way, the state can benefit from the advantages of a blockchain system for its currency. Each digital coin can be pegged against one unit of that national currency. Again, in this case, the trust of the people in the government and factors impacting the monetary policy, economy and the system play an important role in deriving the value of the coins. The coins will merely be a digital representation of the national currency, and hence, will have the same value as the national currency. Many governments and monetary authorities are working along this line. For example, according to a press release on 26 September 2017 by the Department of Economic Development (a Dubai government body), Dubai announced its state-issued crypto-coin, named emCash (DED, 2017). This will be a fine example of a state-issued national crypto-coin.

• Tokens

A token is also a type of crypto-asset but unlike a coin, it does not have its own blockchain platform. That is why it is not the native asset, which is directly associated with a blockchain system. It derives its value from different sources and due to this, it can be divided into the following types:

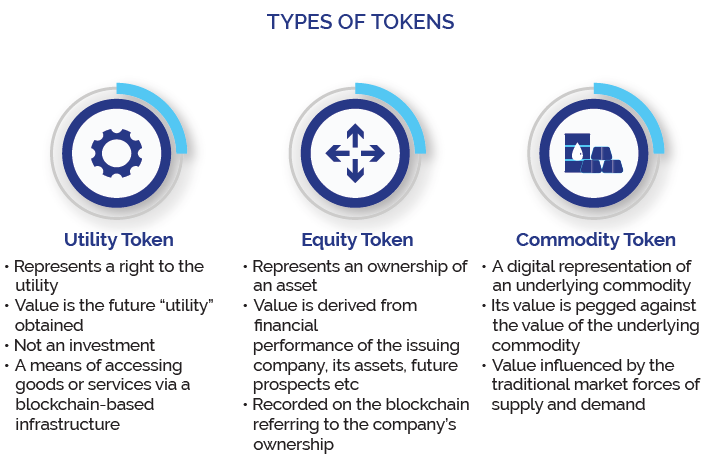

Utility Token

A utility token is a type of crypto asset that represents a right to the utility. The source of value in such crypto-tokens is the future ‘utility’ obtained from that token. A crypto-token can derive its value from the usefulness, benefit or usage attached to that specific token. The benefit attached to that token is actually an outcome of a project for which the token is issued against some capital. However, that benefit or utility is normally realized in the future and not at present. The utility can be in the form of products, services, certain rights, discounts or even a facility or privilege; which can be realized in the future within the native blockchain system.

These types of tokens consist of the feature of accessibility on their native blockchain system so that the users of such tokens can benefit from the services offered by it. A good example of such type of token is FileCoin. FileCoin offers a decentralized storage network by utilizing unused storage space, instead of having storage space at a single point of failure for data. Every space or storage provider is incentivized through FileCoin (the utility token) for its contribution to the system (FileCoin.io, n.d.).

Equity Token

An equity token is a type of crypto asset that represents an ownership interest in a company or corporation. It can be understood as a simple digital representation of stock of a company through a crypto-token. So, the underlying asset of equity token is the share in the assets, business or project of the issuing company, with or without voting rights. Therefore, the value of equity tokens is derived from the financial performance of the issuing company, its assets, future prospects, or any other factor that normally influences the share price of a company.

A company may issue equity tokens instead of shares or stocks for reasons such as blockades in accessing the financial markets, lesser regulatory restrictions, faster processes, or for other various reasons. A good example of equity token is The DAO (Decentralized Autonomous Organization) token, which was created by Slock.it, a German company. The DAO was established in 2016 as a decentralized autonomous organization on the blockchain, and its initial coin offering (ICO) was launched in April the same year. In May 2016, only within one month of its launch, it had raised over US$150 million from more than 11,000 participants, making it the largest ICO at that time. However, just after its creation, the DAO went into serious trouble from many aspects and became a big example of catastrophe (Golomb, 2018). Regardless of its sudden failure, it is important to note that the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) declared that the DAO’s tokens are securities in nature and held that the US federal securities laws are applicable to those tokens (SEC, 2017).

Commodity Token

A commodity token is a digital representation of an underlying commodity. The value of such type of token is pegged against the value of the underlying commodity, which is influenced by the traditional market forces of supply and demand. An example of a commodity token is OneGram, which is fully backed by physical gold and is kept in the issuing company’s vaults. Each token is backed by one gram of gold at the time of launch of the tokens. However, the amount of gold backing each token will increase with time as the transaction fee, after deducing administrative costs, will be reinvested to buy more gold backing each token. The token can be redeemed at any point in time with physical gold. Due to the full-backing of gold and redemption option, the spot price of gold will provide a floor for the token’s minimum price or value. The total supply of the tokens is capped at 12.4 million. On top of that, it is also claimed that OneGram is Shari’a-compliant (One Gram, n.d.). This is a good example of a commodity token.

• Hybrid Tokens

Hybrid tokens are a mixture of more than one category mentioned above, or they can possess some completely extra new features, which makes it difficult to categories them according to the above-mentioned types. Such types of tokens exhibit some complex features and amalgamation of different characteristics. That is why they warrant a separate category. Moreover, this is the most famous type of crypto-tokens. For example, Ether is a token on the Ethereum network, which is operated as a distributed platform. It is primarily a utility token, which is created and used to incentivise the developers of the Ethereum network for writing quality applications and for ensuring that the network remains healthy in terms of resources through their contribution of computing power. However, at the same time, it is used as a form of payment made by the clients of Ethereum to the machines executing the requested operations (Ethereum.org, n.d.). Hence, it is also famous for raising capital through new token sales or ICOs. In addition, ordinary investors also deem it as a medium of exchange, albeit in a very limited manner, and as an asset class that is good for investment.

Another good example of a hybrid token is Petro issued by the Venezuelan State. According to the Petro white paper, “Petro (PTR) will be a sovereign crypto-asset backed by oil assets and issued by the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela on a blockchain platform” (Petro, 2018, p. 12). The white paper further states that it will be a means of exchange for goods and services and will be redeemable for fiat money and other crypto-assets. At the same time, it will be a digital representation of national goods; mainly oil and precious metals, raw materials and other produce available for national and international trade (Petro, 2018). From the white paper, it can be assumed that it is a mixture of commodity token and coin. The commodity is not confined to only one type, but rather a basket of commodities that will support the crypto-asset. On the other hand, since it will be issued by a sovereign state, it will presumably be a legal tender and will hold strong features of a national currency.

Islamic Legal Criteria for Crypto-Assets

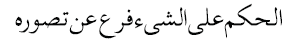

The nature of the Shari’a ruling regarding a thing or case depends on the nature of that thing or the case itself. An Islamic legal maxim reveals this analogy as:

“Judgment [Shari’ah ruling] is to be based on the [proper] knowledge and understanding [of the thing or case].” (Laldin, et al, 2013)

Similarly, for the Shari’a analysis of crypto-assets, the same approach should be applied. The above pivotal discussion has been comprehensively presented to support the proper understanding of the subject matter and its relevant Shari’a ruling. That is why, their main characteristics have been explained to facilitate a juristic deliberation. Moving forward, their takyif fiqhi (characterization from the Islamic legal perspective) is carried out. Technically, takyif fiqhi means determining the nature of a new case for the sake of affiliating it with an original case that has been specified in fiqh with its juristic features, so that the same Shari’a ruling of the original case to the new case can be extended once the similar juristic features have been established in that new case (Shabbir, 2014).

In this regard, some fundamental questions arise: do crypto-assets actually exist or are they imaginary; does Shari’a recognise intangible or virtual assets; can crypto-assets be considered as property or asset from Shari’a perspective and if yes, are they lawful and usable assets (mal mutaqawwam) or unlawful and unusable assets (ghayr-mutaqawwam); how they can be classified from Shari’a perspective; and lastly, how Shari’a rulings can be issued and implemented on them. This section deals with these issues in a thorough and methodical manner.

Existence of Crypto-Assets and Shari’a Stance on Intangible Assets

While explaining crypto-assets above, it has already been argued that the specific digit or number generated through the algorithm or protocol as the result of solving a mathematical problem is real. Although it is a digital asset that only exists on the blockchain platform, it is not imaginary or fictional. That asset is identifiable and distinguishable. It is unique and separated from other coins or tokens. It can be created, destroyed, stored, possessed and transferred. Therefore, it actually does exist.

Nevertheless, it is important to understand whether Shari’a recognizes digital or intangible assets in general. Some jurists, especially Hanafi scholars like Ibn Nujaim and Al-Haskafi are of the view that Shari’a only recognizes corporeal (ayn) or tangible things (Al-Zarqa, 1999). On the contrary, the majority of jurists and scholars consisting of Malikis, Shafis and Hanbalis hold the opinion that Shari’a recognizes both tangible and intangible things and can consider both as property or asset as long as they have value and desirability (Al-Zuhayli, 2010).

Internationally recognized contemporary Shari’a authorities, like Islamic Fiqh Academy of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) and Accounting and Auditing Organization of Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI), have also resolved that intangible or virtual assets are property of inherent monetary value that entitles them to legal protection and that any violations of property rights associated with them are punishable (IDB & IFA, 2000, Resolution No. 43 (5/5); AAOIFI, 2012, Article no 3/3/3/1).

Property/Asset (Mal) in Shari’a and Crypto-Assets

According to the famous Arabic dictionary “Lisan Al-Arab”, mal refers to something which can be possessed (Ibn Manzur, 1975). Al-Isfahani (1992) says that mal is something that is desirable and can be transferred from one person to another person. The Holy Qur’an and the Sunnah of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) have not explained the meaning of mal in clear terms. Hence, jurists differ on its meaning based on their own understanding, custom and etymological usage during their period. Al- Zuhayli (2010) categorises the scholars into two groups in this regard: Hanafi scholars and majority scholars.

• Definition of mal according to Hanafi scholars

Ibn Nujaim (2002) is of the view that mal is something that is desirable and can be physically stored for the time of need. Anything can be recognised as mal when all or a group of people accept and act as if something is mal. The same definition of mal is given by another Hanafi jurist, Ibn Abidin. He opines that mal is something that is created for the benefit of humans and can be physically stored and used at the time of need (Ibn Abidin, 2009). According to this definition, there are two attributes to consider something as mal: (1) it would be desirable by a human being and (2) it would be capable of being physically stored for the time of necessity. According to this definition, usufructs and rights (such as riding a car or living in the house, copyrights, etc.) are not mal because these things cannot be physically stored. Although, the above-mentioned definitions do not limit the definition of mal to tangible or corporeal things (ayn) in clear terms, it can be understood from their context.

• Definition of mal according to majority of scholars

Most jurists and scholars (including Malikis, Shafis, and Hanbalis) are of the view that mal is not limited to tangible things. Their view is that mal also includes intangible things as well as benefits and rights with certain conditions. Al Zuhayli (2010) explains that the majority of scholars opine that mal refers to everything that has value and is compensated for if it is destroyed.

• Preferred definition of mal

The contemporary Hanafi scholar, Taqi Usmani, is of the view that if intangible things such as rights and benefits become valuable things according to custom (urf), then it should be treated as mal. He further explains that prevalent custom (urf) of business plays a pivotal role in determining benefits (manafi) and rights (huquq) as mal. This is why, for example, copyrights, patents, trademarks, and goodwill are considered as mal – even though these things are intangible because these are very valuable things in the custom of business and trade in today’s world (Usmani, 2015).

Likewise, another contemporary Hanafi jurist, Khalid Saifullah Rahmani, argues that tangibility is not a core condition for determining something as mal. According to him, the core condition for the criterion of mal is storability. He explains that in the old times, only tangible things could be stored. It was difficult to imagine at those times that intangible things, such as benefits and rights can also be stored and protected. That is why the classical Hanafi jurists only considered tangible things as mal. However, nowadays, since intangible things can also be well protected and stored, there is no need to insist on this condition (Rahmani, 2010).

It is evident that the view of contemporary Hanafi jurists also converges with the majority’s opinions, and there is no real difference between contemporary Hanafi jurists and other jurists on the definition of mal. Moreover, the contemporary custom of the people also supports the understanding of intangible assets being mal. Therefore, this view is preferred. Based on the preferred view, it can be argued that crypto-assets are intangible or digital assets, which can be recognized as mal (property or asset) in Shari’a. However, whether they are valid (mutaqawwam) or invalid (ghayr-mutaqawwam) type of assets needs further scrutiny. The next section delves into this discussion.

Mal Mutaqawwam and Crypto-Assets

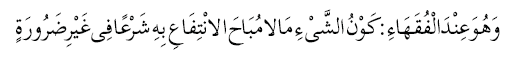

Mausooah Fiqhiyyah (2007) defines mal mutaqawwam as:

“According to [Hanafi] jurists, it is an asset which Shari’ah allows to derive benefit from without a dire need.” (Mausooah Fiqhiyyah, 2007, vol. 13, p. 168)

It means that anything that has commercial value and Shari’a allows benefiting from it in normal circumstances, is called mal mutaqawwam. In other words, it is something permissible and exchangeable for a price. On the contrary, if something has a commercial value but it is an impermissible object, it is considered as mal ghayr-mutaqawwam. An example of mal ghayr-mutaqawwam is wine. It can be possessed, stored and has a commercial value; yet it is not allowed for Muslims to derive benefits from it in any form. Therefore, wine is considered as mal ghayr-mutaqawwam for Muslims. Having said that, it may have a commercial value for non-Muslims and they are also allowed to benefit from it, hence wine is mal mutaqawwam for non-Muslims (Al-Kasani, 1986).

Rahmani (2010) explains that if something has the following required attributes, then it can be considered as mal (mutaqawwam): • It is permissible and lawful in Shari’a (mutaqawwam). That is why dead objects and alcohol are not considered as mal (mutaqawwam). • It is capable of being owned and possessed. • It has some valid uses and benefits.

Moreover, he further states that if the customary practice of people determines and treats something that is already permissible in Shari’a as mal, it would automatically be considered as mal mutaqawwam. This is another reason that many contemporary Hanafi scholars have considered various rights and benefits (copyrights, patents and trademarks etc.) as mal since people in their customary practice treat them as commercially valuable things. It seems that urf or customary treatment of something as mal can overcome the third condition mentioned above. In other words, if something does not have any intrinsic use or benefit, but it fulfils the first two conditions, and people treat it as mal, then it can be considered as mal mutaqawwam.

Therefore, if a crypto-asset can be owned and possessed, digitally represents the value of something that is permissible and lawful in Shari’a, and has commercial uses and benefits; then it can be considered as mal mutaqawwam (like in the case of tokens and hybrid tokens). However, if a crypto-asset does not have any intrinsic commercial use or benefit, but people consider and accept it as commercially valuable based on their customary practice; it still can be considered as mal mutaqawwam (like in the case of coins). Although it seems paradoxical that if something does not have any intrinsic use or benefit, why people would consider it as commercially valuable. However, this has been proven to be true in the case of Bitcoin. Bitcoins or other digital coins offer a way of digitally storing and transferring value. Although, they do not have any intrinsic use, yet people accept them as valuable.

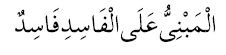

On the contrary, if the value of a crypto-asset is based on something that is not allowed in Shari’a per se, or it represents something that Shari’a does not allow to derive benefits from; then that crypto-asset is considered as mal ghayr-mutaqawwam. Consequently, it will become an impermissible or haram asset itself. It is based on an Islamic legal maxim, which is states:

“Anything which is based on a void thing is void [itself].” (Ibn Nujaim, 1999, p. 339)

Criteria for Shari’a-Compliance of Crypto-Assets

From the previous discussion, it can be argued that it is possible to create a Shari’a-compliant crypto-asset or to establish criteria for Shari’a-compliance of the existing crypto-assets to distinguish between Shari’a-compliant and non-compliant ones. It has been discussed earlier that in principle, Shari’a recognizes and accepts intangible assets (or digital assets in this case) as mal. However, for crypto-assets to qualify as mal mutaqawwam (valid assets), certain conditions or parameters can be proposed. These parameters can form the criteria for Shari’a compliance of crypto-assets. They can be stated as:

1. The native blockchain protocols, which provide the digital platform for the crypto-asset should be designed in such a manner that they do not fundamentally consist of haram or impermissible element. For example, the issuance of new crypto-tokens should not be based on interest (riba).

2. The main legal contracts forming the contractual and transactional framework for the crypto-asset should not violate any Shari’a principles.

3. The underlying product/service/commodity/business entity should be Shari’a-compliant. For example:

a. In the case of the utility token, the utility offered in the form of product or service should be Shari’a-compliant.

b. In the case of equity token, the issuing company and its business activities should be Shari’a-compliant. Moreover, it is important that the company should also fulfil the financial ratios’ criteria of Shari’a compliance set by certain stock screening bodies.

c. In the case of commodity token, the underlying goods should be Shari’a-compliant.

4. The crypto-asset by design should not contain any impermissible element. For example, it should not be attached or linked with the underlying project/product/service/goods in such a manner that it raises concerns about gharar, riba, or violates any other Shari’a principles.

5. The main features and characteristics of the crypto-asset should not include any impermissible element. For example, the use of crypto-asset should not be exclusively for impermissible purposes or haram activities.

In addition to the above parameters, special Shari’a requirements and conditions, which are exclusive for any specific transaction, product or service involved in the crypto-asset should also be fulfilled. However, this can be decided on a case-by-case basis.

Conclusion

The recent phenomenon of crypto-assets is a new dimension of technological advancement in the global financial sphere. Due to the absence of any close precedent in the classical fiqh literature regarding the issue of crypto-assets, it requires ijtihad (juristic analogy based on the main sources of Shari’a) to issue a Shari’a ruling on the permissibility and impermissibility of crypto-assets. Subsequently, it is vital to comprehensively understand the fiqhi characterization and taxonomy of such type of assets, so that their Shari’a ruling is based on the correct ijtihad and proper understanding. It has been deliberated in this chapter that crypto-assets are a type of digital assets. In relation to this, Shari’a recognizes intangible assets as a form of property or mal. However, the main question is whether such type of assets can be considered as mal mutaqawwam (valid asset).

To answer that question, it has been stated that there are various types of crypto-assets, mainly: (1) coins; (2) tokens; and (3) hybrids. Each of these types demonstrates specific characteristics and digitally represents a diverse array of business activities, commodities, rights and benefits. Due to unique protocols and different sources and types of underlying projects/products/services where such assets derive their value from, it may not be a correct approach to issue a general Shari’a ruling for all the crypto-assets. Each type of crypto-assets requires detailed analysis to investigate its nature, fiqhi characterization and features.

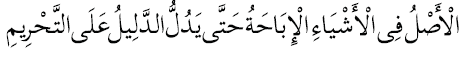

In view of that, this chapter proposes criteria for Islamic legal analysis of crypto-assets to facilitate the creation of a Shari’a-compliant crypto-asset or to know whether an existing crypto-asset is Shari’a-compliant. For a Shari’a-compliant crypto-asset, it is crucial that its main characteristics, the process of issuance and distribution, underlying project/product/ service and exclusive usage and benefits do not violate any Shari’a principles. With these parameters and criteria, it is possible to have a Shari’a-compliant crypto-asset, because:

“The original principle in [Shari’ah ruling of] things [or transactions] is permissibility unless evidence [from the Shari’ah sources] proves its impermissibility.” (Al-Suyuti, 1983, p. 60)