Developed by Edbiz Consulting in 2011, Islamic Finance Country Index (IFCI) is the oldest index for ranking different countries with respect to the state of Islamic banking and finance (IBF) and their leadership role in the industry on a national level and benchmarked to an international level. IFCI has evolved over the last nine years, with two adjustments (first in 2018 and the second this year). These adjustments aimed at normalizing the data over the time series (2018) and to reflect on our increased intelligence into some key IBF markets (2019).

The data has now started achieving a meaningful length. In 2011, when IFCI was launched, there was no previous benchmark to assess the performance of the countries included in the sample. With nine years in running, the index has started exhibiting some characteristics of time series data. In 2017, we started drawing some implications from the past performance of IBF in individual countries and on a global level for the future growth of the industry.

The IFCI was initiated with the aim to capture the growth of the industry, and providing an immediate assessment of the state of IBF in each country. With the nine-year data since its inception, IFCI can now be used to compare the countries not only in a given year but also over time. As more countries open up to IBF, the index will provide a benchmark for nations to track their performance against others. Over time, the individual countries on the index should also be able to track and assess their own performance.

The IFCI shows the growth of IBF in an objective manner, making it a useful tool for industry analysis and comparative assessments. We recommend that the readers use previous GIFRs (2011-18) to have a comprehensive view on IFCI.

IFCI 2019

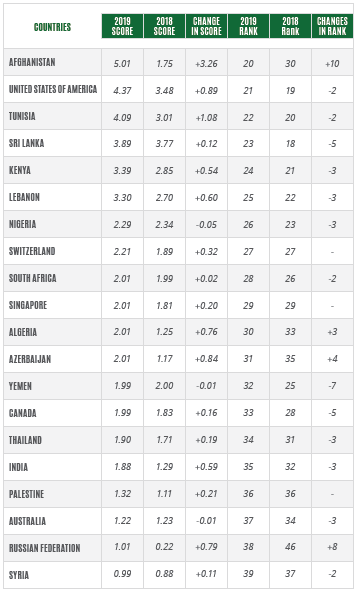

Table 1 presents the latest IFCI scores and ranks. Following are some of the important observations:

- Indonesia ranks number one, with 81.93 score, overtaking Malaysia that dominated the index since 2011. The previous holders of the top position have included Iran and Malaysia. Prior to this year, Malaysia was ranked number one for three years in a row, taking over from Iran in 2016. Indonesia has jumped 5 positions up to capture the top slot this year.

- There is no change in ranks of four countries (Turkey ranked 13; Switzerland ranked 27; Singapore ranked 29; and Palestine ranked 36). This represents the largest annual variation in the annual ranking of IFCI since its inception.

- There are 44 countries that have witnessed changes in their IFCI scores: 14 positively and 28 negatively. This is in contrast to the last year when only 14 countries experienced change in ranking.

- It must be noted that there has been positive changes in the IFCI scores for all the countries except four, most notably Saudi Arabia which experienced 6.01 points decrease in its IFCI score. This means while IBF has strengthened in most countries, Saudi Arabia has witnessed weakening of its IBF market in the past one year.

- This year, Morocco took the biggest leap and improved its position from number 48 to 19. Morocco is fast assuming mainstream relevance in the global IBF, as it is now one of the top 20 IBF markets in the world. Last year, the biggest leap was taken by Kazakhstan that has further improved its ranking from being 24th last year to the 18th position this year. Afghanistan is another gainer, which jumped 10 positions from being 30th last year to enter the top 20 list. Brunei Darussalam and Sudan are two other net gainers, with 8 and 6 positions improvement, respectively.

- Countries in the GCC (barring Oman) and the likes of Pakistan, Jordan, Tunisia, Sri Lanka, Kenya, Lebanon, India, Australia, Gambia and Senegal are net losers.

- The data also exhibits the robustness of the sample and its size. There are 48 countries included in the sample (less than some other indices being reported in the industry). The IFCI score falls below 1.00 at the 39th position, implying that the information contents provided by the 10 countries is almost negligible.

- It is also interesting to note that average IFCI score increased this year to 16.17 from 11.12 last year.

“THIS YEAR, MOROCCO TOOK THE BIGGEST LEAP AND IMPROVED ITS POSITION FROM NUMBER 48 TO 19. IN THIS WAY, MOROCCO IS FAST ASSUMING MAINSTREAM RELEVANCE IN THE GLOBAL IBF, AS IT IS NOW ONE OF THE TOP 20 IBF MARKETS IN THE WORLD.”

What Led to Improvement in IFCI Ranks of the Sampled Countries

Movements in IFCI are determined by changes in values of its constituent factors. Five of the 14 countries that have shown improvement in IFCI are discussed below. Before we go into details about specific countries, it is important to clarify that the positive changes in the IFCI scores and ranking may be explained with the help of:

- Changes in the constituent factors affecting the index; and

- Improvement in our intelligence into the individual markets.

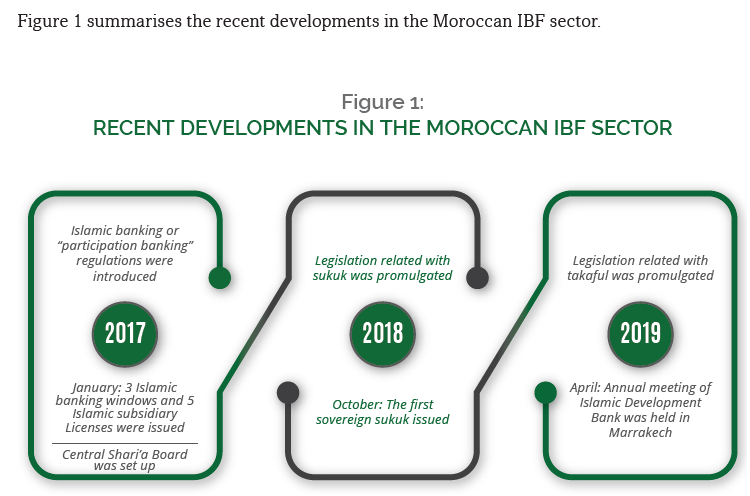

Morocco: +29

Morocco experienced the biggest jump in IFCI ranking, from 48 to 19. Our analysis suggests that 60% of the change in the ranking of Morocco can be explained with the help of the improved publicly available information and Cambridge IFA’s (our research partner) proprietary intelligence into the Moroccan IBF market. The remaining 40% of the improvement is owning to positive changes in the constituent factors of IFCI.

IBF-related activities in Morocco were scant before 2015 when there were no clear regulatory guidelines for Islamic banks and financial institutions. Since 2017 when Islamic banking regulations were introduced in the country, a very large number of banks and financial institutions have started offering Islamic financial services. Our 2018 data started capturing the specific regulatory information and its consequent improvement in the IBF-related infrastructure, and this is due to the improvement in the intelligence that Morocco has witnessed the reported huge jump in its IFCI ranking. Having said that, the nascent IBF industry in the country continues to face challenges. The good news is that the government and other stakeholders have shown serious intent to resolve the issues surrounding the growth of IBF in the country. Following the legislation on sukuk, the government issued its first sovereign sukuk of MAD1 billion (US$105 million) in 2018. This year, the government has finalized the legislation on takaful, which is expected to spur growth in this field as well as provide adequate tools for liquidity management for Islamic financial institutions in the country.

As an important member of the OIC and its sister organisations like Islamic Development Bank (IsDB), it has continued to be central to many developments. Earlier this year, IsDB held its annual meeting in Marrakech, which focused on the development of IBF, among other things on its agenda.

“Brunei Darussalam has jumped this year to the 6th position from its previous 14th, ahead of all the six GCC countries except Saudia Arabia.”

Afghanistan: +10

After emerging from a prolonged war on terrorism and political instability, Afghanistan has started showing its relevance to a number of fields, including IBF. Now, there is one full-fledged Islamic bank – Islamic Bank of Afghanistan – operating in the country, along with some other players. There is growing awareness of IBF in Afghanistan, as a number of bodies have started offering instruction and trainings in this field of increasing importance for the country. The country is also included in the list of 5 member states of Asian Development Bank (ADB), which will benefit from the ADB’s drive to capacity building and public awareness around IBF in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, the Kyrgyz Republic and Kazakhstan.

Although there is only one full-fledged Islamic bank in the country at present, the country has been on the radar of various foreign investors from the Middle East. There are some prospects of attracting investments from other countries, especially Malaysia that has been a major IBF market for more than a decade.

Brunei Darussalam: +8

Brunei Darussalam has jumped this year to the 6th position from its previous 14th, ahead of all the six GCC countries except Saudi Arabia. This is a remarkable position that Brunei Darussalam enjoys in the global Islamic financial services industry.

Brunei Darussalam is in the good company of other two important players in the global Islamic financial services industry, i.e., Indonesia and Malaysia (ranked first and second, respectively). These three countries make up the second strongest regional block in the global Islamic finance, after the GCC (see below for further classification of countries with respect to IFCI).

Following are the salient features of the IBF sector of Brunei Darussalam:

- Share of IBF in the total national financial sector > 50%1

- The largest bank in the country is an Islamic bank – Bank Islam Brunei Darussalam

Sudan: +6

Before the political unrest in the country, Sudan’s banking sector (which is 100% Shari’a-compliant on a systemic level) was doing extremely well. This is reflected in its improved ranking of 5 from 11 last year. The largest bank in the country – Bank of Khartoum – is a bank that has received lot of awards and recognition for the innovative approach it has adopted in the wake of adverse macroeconomic conditions and international sanctions. Our research suggests that Sudan has a lot more to offer in terms of leadership within the country and outside it. The country has pioneered a number of tools and products for financial inclusion besides the innovative approach it has adopted for product development and structuring.

Indonesia: +5

This year, Indonesia becomes the top-ranked country in terms of its leadership and potential in global IBF. The factors that led to its elevation to the top rank include:

1. The highest level political support: The President Joko Widodo himself chairs a national committee (Komite Nasional Keuangan Syariah, also known as KNKS in its abbreviated form) to promote Islamic finance in the country.

2. The fact that Indonesia is the largest economy in the OIC-block, both in terms of population and the GDP (see Table 6), and the top-level government support has now emerged for IBF in the country, Indonesia is bound to become an unrivalled global leader in this respect. Its IFCI top rank seems like the start of a long-lived leadership role.

3. Regulatory developments in the field of IBF have also greatly helped the country in becoming the top IBF market. The role of Otoritas Jasa Keuangan (OJK) – Financial Services Authority of Indonesia – is very commendable in this respect. OJK and Bank Indonesia (the central bank) have closely worked to create a level-playing field for IBF in the country.

4. Ecosystem for IBF has improved significantly in the country. Halal tourism, zakat collection and distribution, waqf bonds/sukuk and the related regulatory framework are just a few examples of the impressive recent track record of Indonesia in IBF.

5. Private sector has also played a tremendously important role in the promotion of IBF. Bank Syariah Mandiri (BSM) has now emerged as a global leader in IBF, although its major focus remains on the national/domestic market. In the past few years, BSM has been recognized by the likes of Global Islamic Finance Awards (GIFA) and Islamic Retail Banking Awards (IRBA) for its emerging leadership role in the global Islamic financial services industry. Other players like BTPN Syariah have also started becoming extroverts.

Classification of Countries with Respect to IFCI

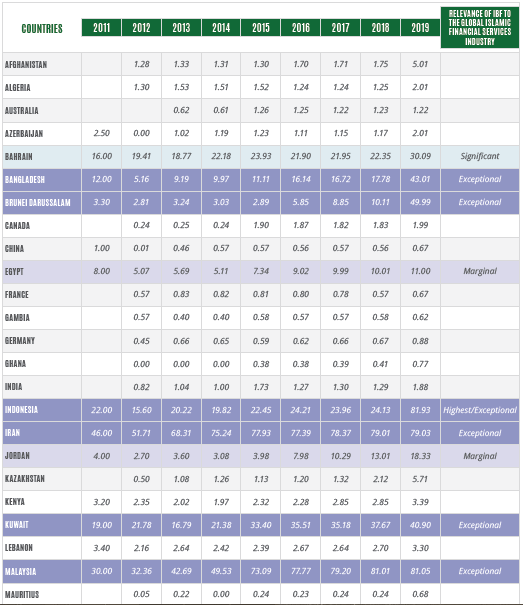

Table 2 presents the latest IFCI scores, along with that of the previous eight years. Based on the scores, the table classifies the sampled countries into six groups:

1. Insignificant: The countries with the latest IFCI score of less than or equal to 10 (IFCI ≤ 10) – 32 countries;

2. Marginal: The countries with the latest IFCI score of more than 10 but less than or equal to 20 (10 < IFCI ≤ 20) – 3 countries;

3. Moderate: The countries with the latest IFCI score of more than 20 but less than or equal to 30 (20 < IFCI ≤ 30) – 2 countries;

4. Significant: The countries with the latest IFCI score of more than 30 but less than or equal to 40 (30 < IFCI ≤ 40) – 2 countries;

5. Exceptional: The countries with the latest IFCI score of more than 40 (IFCI > 40) – 9 countries; and

6. Highest3: The country that tops the list (in this case, Indonesia, which has an IFCI score of 81.93).

This means that there are only 16 countries where IBF has assumed any meaningful relevance to mainstream banking and finance. These countries are presented later in the chapter along with an analysis in light of some macroeconomic indicators (see Table 7).

“Private sector has also played a tremendously important role in the promotion of IBF. Bank Syariah Mandiri (BSM) has now emerged as a global leader in IBF, although its major focus remains on the national/domestic market.”

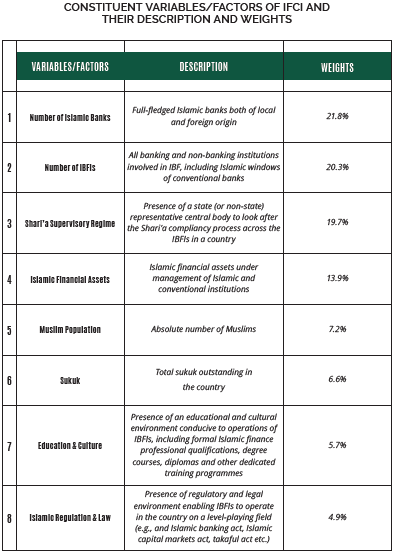

Box 1: A NOTE ON DATA AND METHODOLOGY

IFCI is based on multivariate analysis. For the construction of the index, data was collected on a number of variables, including macroeconomic indicators of the countries included. The data was then tested to see if it contained any meaningful information to draw conclusions from. After consideration of different multivariate methods, it was decided to use factor analysis to identify the factors that may influence IBF in the countries included in the sample.

In order for factor analysis to be applicable, it is important that the data fits a specification test for such an analysis. The Kaiser-Meyer-Oklin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy is used to compare the magnitudes of the observed correlation coefficients in relation to the magnitudes and partial correlation coefficients. Large values (between 0.5 and 1) indicate that factor analysis is an appropriate technique for the data at hand. If the value is less than that, then the results of the factor analysis may not be very useful. For the data we used, we found the measure to be 0.85, which made it reasonable for us to use factor analysis.

Batlett’s test of sphericity is another specification test that tests the hypothesis that the correlation matrix is an identity matrix indicating that the given variables are unrelated and therefore unsuitable for structure design. Smaller values (less than 0.05) of the significance level indicate that factor analysis may be useful with the data. For the present purposes, this value was found to be significant (0.00 level), which means that data was fit for factor analysis.

Factor analysis was therefore run to compute initial communalities to measure the proportion of variance accounted for in each variable by the rest of the variables. In this manner, we were able to assign weights to all eight factors in an objective manner.

By following the above method, we have been able to remove the subjectivity in the index. The weights along with the identified factors make up the IFCI. The weights point to the relative importance of each constituent factor of the index in determining the rank of an individual country.

There are over 70 countries involved in IBF in some way or another. However, due to limitations imposed by authenticity, availability and heterogeneity of the data, IFCI was launched in 2011 with only 36 countries. Over the next three years, the availability of data allowed us to include and other six countries to make the sample size of 42. The current sample stands at 48, and we believe that this is a robust enough number to analyze the state of affairs of the global Islamic financial services industry. Information contents of the data for other countries is not instructive at all.

The data used comes from different primary and secondary sources, but in its collective final form becomes the proprietary data set of Edbiz Consulting, which collects, collates and maintains it.

We collect data on eight factors/variables for the countries included in IFCI. The variable and their respective weights are described in the following table.

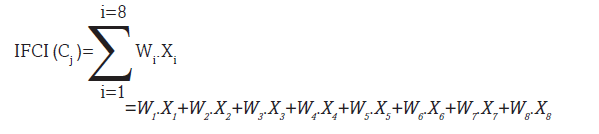

THE GENERAL MODEL

used for the construction of IFCI is as follows:

where

Cj = Country j including in the index

Wi = Weight attached to a given variable/factor i

Xi = A given variable/factor I included in the index

The countries are ranked according to the above formula every year, using the updated annual data.

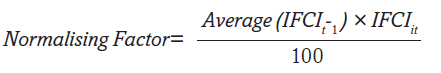

In 2016, a major adjustment exercise was undertaken to take into account some of the time-series characteristics of the data. The primary objective of this exercise was to normalize the data over the time. We adopted a methodology based on a weightage system that we adopted to construct a normalizing factor.

The normalizing factor used in the adjusted IFCI was calculated by the following formula:

where

Average(IFCIt-1 )= Average of IFCI scores for all the countries included in the sample of the previous year (t-1); and

IFCIit = IFCI score for an individual country i in the current year (t).

This normalizing factor allows us to neutralize the purely statistical effect of data movements on IFCI score in such a way that the overall ranking in a given year remains unaffected.

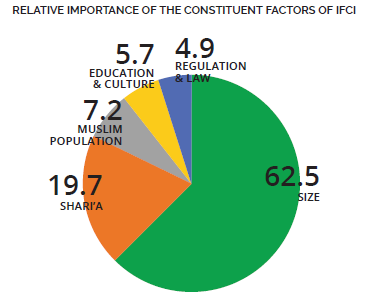

As the above table and figure suggest, size of Islamic financial services industry as captured by four factors (namely, number of Islamic banks, number of IBFIs, volume of Islamic financial assets, and the sukuk outstanding) is the most important factor in the index, explaining 62.6% variation. Therefore, it is superior to the unilabiate analyses that focus on just size of the industry in a given country. Furthermore, size in itself is not enough to capture the relative importance of IBF in a country. It is equally important to consider depth and breadth of the industry. Hence, both the size of Islamic financial assets and the number of IBFIs are included. Furthermore, the inclusion of sukuk, which accounts for 15% of the global Islamic financial services industry, as a separate factor is also useful.

Although the other factors collectively explain 37.4% variation in the index, their inclusion is important as they give a comprehensive view on the state of affairs of IBF in a country.

It must be clarified that IFCI is a positive measure of the state of affairs of IBF and its potential in a country, without taking a normative view on what should be the important factors determining size and growth of the industry, and their relative importance (i.e., weights).

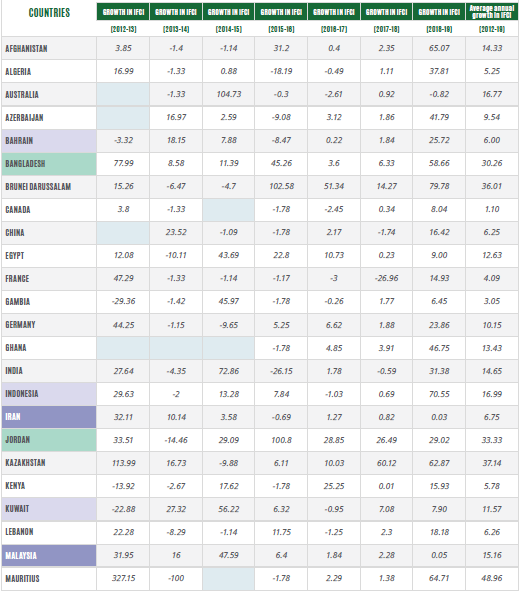

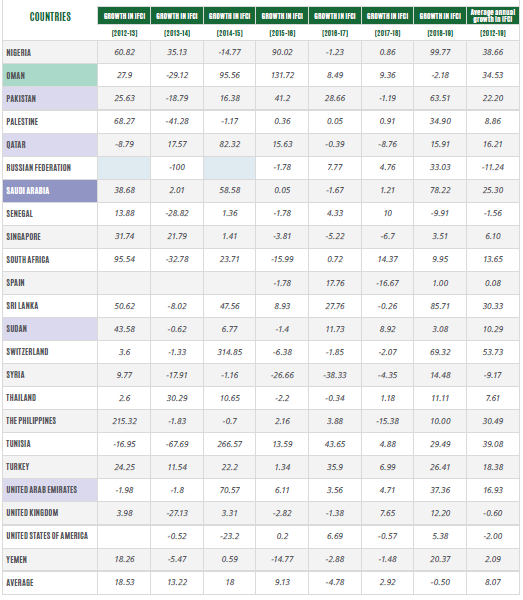

GROWTH IN IFCI: 2012-19

Table 3 presents growth in IFCI over the last 8 years, showing that overall annual growth in the index between 2011 and 2019 has been 8.07%. This should, however, not imply that the growth has been evenly distributed in the countries included in the sample. There are 5 countries where IBF has on average gone down in significance over the last eight years. These include: the Russian Federation, Senegal, Syria, the UK and the USA.

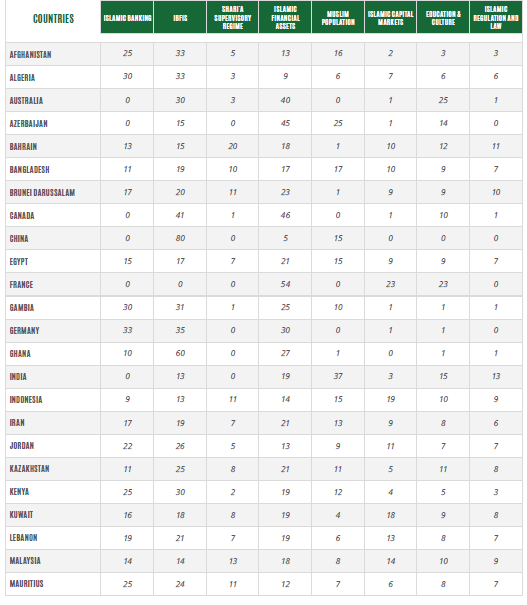

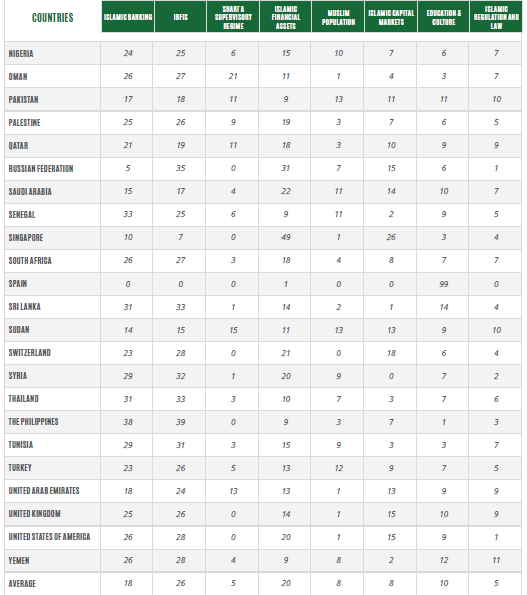

Table 4 presents the contributions of composite factors to IFCI for the year 2017. On the basis of relative contributions of these factors, one may classify the countries into three broad categories:

1. Comprehensively balanced;

2. Balanced; and

3. Skewed.

“THERE ARE 5 COUNTRIES WHERE IBF HAS ON AVERAGE GONE DOWN IN SIGNIFICANCE OVER THE LAST EIGHT YEARS. THESE INCLUDE: THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION, SENEGAL, SYRIA, THE UK AND THE USA.”

PERCENTAGE CONTRIBUTIONS OF COMPOSITE FACTORS TO IFCI

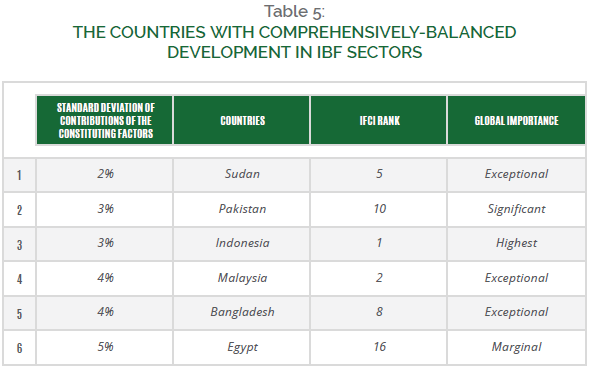

Countries with Comprehensively-balanced Development in IBF

These are the countries wherein constituting factors contribute evenly to the development of IBF sector. A country is categorised as one with comprehensively-balanced development in IBF if the standard deviation of the contributions of the composite factors is less than or equal to 5%.

As Table 5 suggests, there are only 6 countries, namely, Sudan, Pakistan, Indonesia, Malaysia, Bangladesh and Egypt, which have undergone comprehensively-balanced development in their respective IBF sectors.

It is interesting to note that the countries with the highest Muslim population (e.g., Indonesia, Pakistan, Bangladesh) have developed their IBF sectors more comprehensively than other leading countries like Iran, Saudi Arabia and other important players in the GCC region.

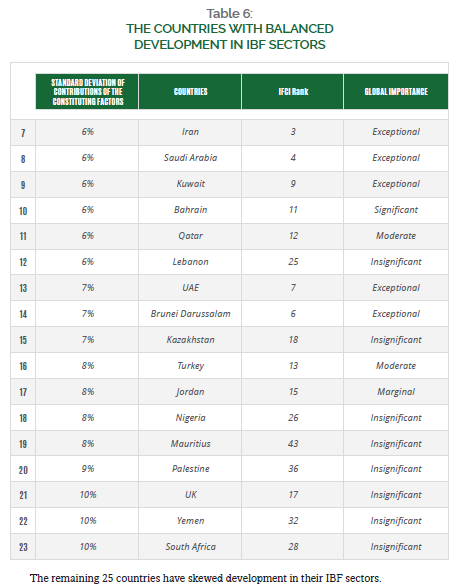

Countries with Balanced Development in IBF

There are 17 countries with balanced developments in the IBF sector. A country is categorized as the one with balanced development in IBF if standard deviation of the contributions of the composite factors is more than 5% but less than or equal to 10%. Table 6 presents the countries with balanced development separately.

THE COUNTRIES WITH BALANCED DEVELOPMENT IN IBF SECTORS

The remaining 25 countries have skewed development in their IBF sectors.

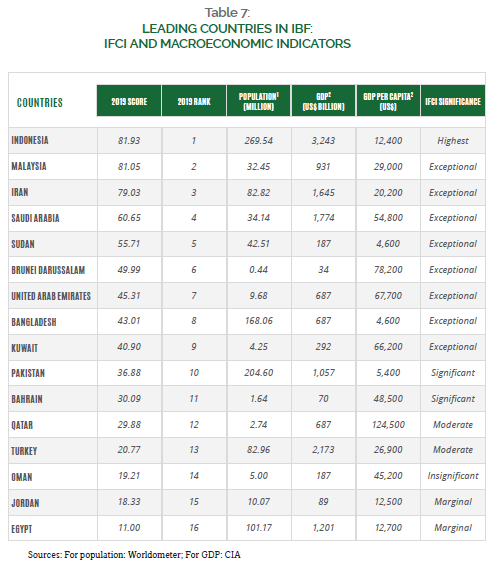

IFCI and Macroeconomic Indicators

There are only 16 countries in the world, which are playing a role of some significance in the global Islamic financial services industry. These are separately listed in Table 7, with their geographical location, and some basic information on their demographics and economies.

The sample of leading countries in IBF is a mixed bag, including relatively developed countries like Malaysia, the countries in the highest per capita income bracket (e.g., Qatar), and those falling in the list of the countries with the poorest populations (e.g., Bangladesh). This is both good news and bad news. It is good because it shows that IBF can work in all environments and can serve all segments of the societies. The other side of the coin may reveal, however, that IBF has not contributed to national socio-economic agendas, as there is no systematic relationship between the degree of economic development and the incidence of IBF. At least the limited data at hand does not suggest so!

LEADING COUNTRIES IN IBF: IFCI AND MACROECONOMIC INDICATORS

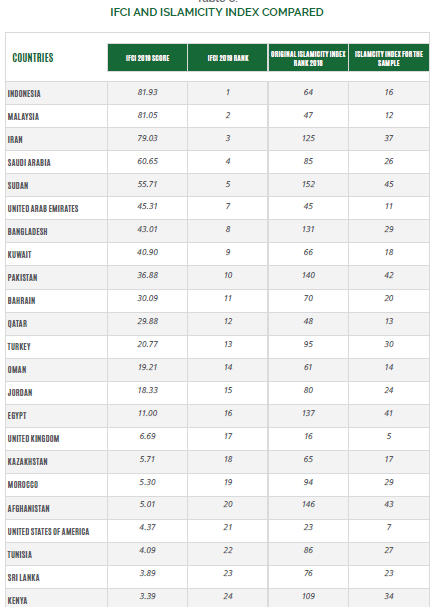

IFCI and Islamicity

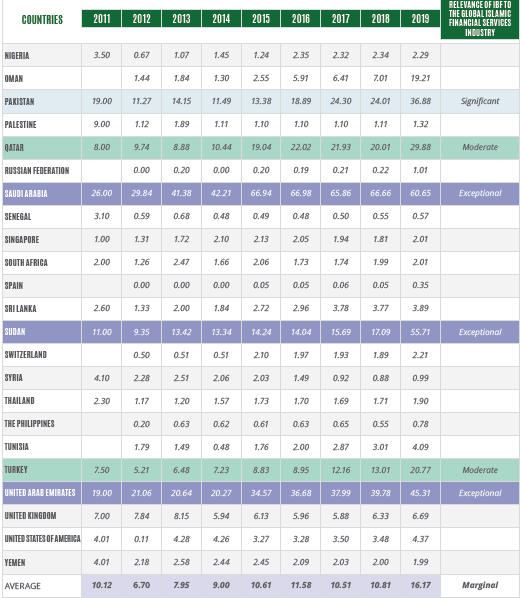

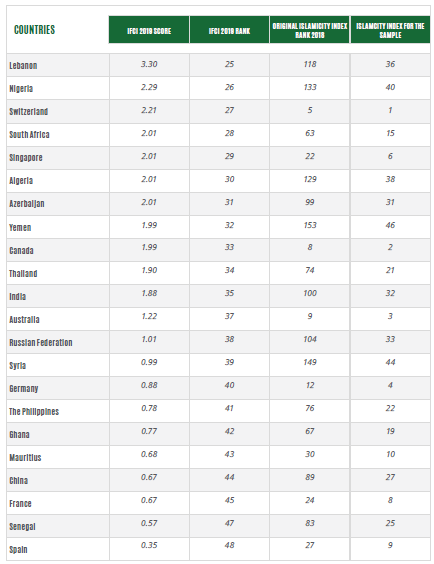

Economist Hossein Askari popularized an Islamicity Index, which is now produced under Islamicity Foundation. Last year’s GIFR presented a comparison between IFCI and Islamicity Index for which the data was available till 2016. This year’s report continues from the previous year, as since then the Islamicity Index 2018 has been released. The comparison should indicate similarities or differences between the two indices.

Table 8 compares the values of IFCI for 2019 with those of Islamicity Index for the year 2018. It is interesting to note that the top country on IFCI, i.e., Indonesia, is 64th on the Islamicity Index. Switzerland is Number 5 (the highest position attained by a country on Islamicity Index, which is also ranked under IFCI). Switzerland is 27th on the IFCI ranking.

Our analysis suggests that there is no clear correlation between the two indices, with very high standard deviation between the two indices.

“Last year’s GIFR presented a comparison between IFCI and Islamicity Index for which the data was available till 2016. This year’s report continues from the previous year, as since then the Islamicity Index 2018 has been released. The comparison should indicate similarities or differences between the two indices.”

IFCI AND ISLAMICITY INDEX COMPARED

Size & Growth of the Global Islamic Financial Services Industry

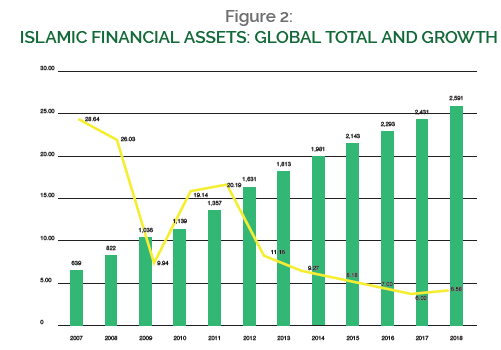

Islamic banking and finance (IBF) is growing in popularity. After four years of decline in growth rate, the industry has once again picked up to register annual growth in assets of 6.58% during 2018, from US$2.431 trillion at the end of 2017 to US$2.591 trillion at the end of 2018 (see Figure 2). In dollar terms, there was a net increase of US$160 billion in the global stock of Islamic financial assets.

Banks continue to dominate in terms of global Islamic AuM, with 79% of the global Islamic financial assets held by Islamic banks and Islamic windows and subsidiaries of conventional banks. Out of the total Islamic financial assets, around 60% are held by full-fledged Islamic banks (US$1.56 trillion in volume).

With the fifth consecutive year of single-digit growth, this is certainly the right time for the industry stakeholders to ponder over the real reasons for the slow-down. Is it just a natural and temporary slow-down caused by macroeconomic conditions in the countries where IBF is significant, or are there some fundamental issues that have started biting the industry? Having said that, it seems as if the industry has once again started picking up, as evidenced by slight increase in growth rate this year.

“MOST OF THE GROWTH STEMS FROM ISLAMIC BANKING, WITH ISLAMIC ASSET MANAGEMENT BEING THE LEAST GROWING SEGMENT.”

In the 2016 and 2018 reports, we attributed the slow-down in growth to some structural issues, stalled innovation and wider macroeconomic factors. Furthermore, security and law & order in a number of Muslim countries (e.g., Syria, Sudan and Iraq, etc.) have also hampered the growth. However, it appears as if the recent surge has been caused by returning peace and improving law and order in a number of countries. Also, oil prices have started improving in favor of IBF.

“IT APPEARS AS IF THE RECENT SURGE HAS BEEN CAUSED BY RETURNING PEACE AND IMPROVING LAW AND ORDER IN A NUMBER OF COUNTRIES. ALSO, OIL PRICES HAVE STARTED IMPROVING IN FAVOUR OF IBF.”

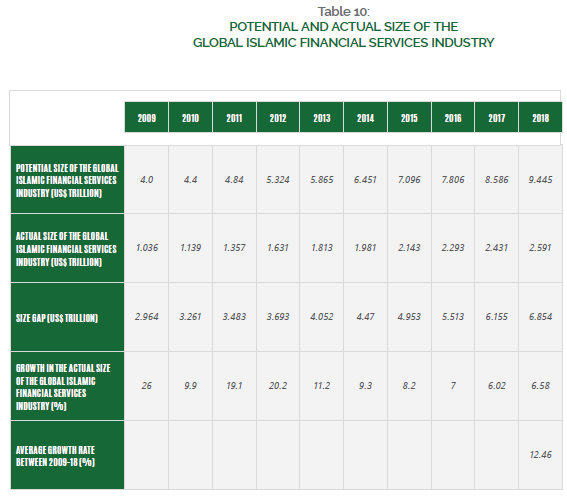

Potential and Actual Size of the Global Islamic Financial Services Industry

Potential size of the global Islamic financial services industry can be defined as the assets under management (AuM) of the institutions offering Islamic financial services to all those who would like to have access to such services, and to all those who would like to use Islamic financial services but have excluded themselves voluntarily from the financial services market because such services are not available (GIFR 2016, p. 39). Actual size of the global Islamic financial services industry is the AuM of all the institutions offering Islamic financial services, i.e., stand-alone Islamic banks, Islamic banking windows and subsidiaries of conventional banks and financial institutions, stand-alone takaful and re-takaful companies, takaful and re-takaful windows and subsidiaries of conventional insurance and reinsurance companies, Islamic microfinance institutions (whether microfinance banks or non-bank takaful provides), Islamic financial assets held by Islamic fund managers and Shari’a-compliant asset management arms of conventional fund management companies, and also include sukuk outstanding.

POTENTIAL AND ACTUAL SIZE OF THE

GLOBAL ISLAMIC FINANCIAL SERVICES INDUSTRY

As Table 10 shows, there is a growing gulf between potential and actual size of the global Islamic financial services industry. With nearly US$3 trillion of deficit in 2009, the gap has now more than doubled. This implies that the catch-up time required for the industry to realize its potential is ever-increasing. GIFR 2014 reported the catch-up period to be an estimated 17 years, which has now gone well beyond 40 years.