While Islamic finance has enjoyed somewhat stable growth for more than four decades, development in information and communication technology (ICT) in recent years is tremendous and recently it completely reached the huge continent of financial industry in various types of forms and manners.

The word “FinTech”, which literally means financial services enhanced by high use of ICT, may no longer be a suitable expression, considering the fact that various innovations in financial industry these days involve extensive use of ICT, including consumer banking and remittance on smartphone applications and the internet, cryptocurrencies, AI (artificial intelligence)-based Robo-advisors, to name just a few.

Under this background, this chapter explores the possibilities of Islamic FinTech, especially in terms of its social finance nature, which is in line with the religious values of Islam.

FinTech Reaches Islamic Finance

FinTech has started to enjoy growing interest in the financial industry all over the world. Ten years ago, the word itself did not even exist, but we are sure that it will have a huge impact on, and shape, financial business in coming five years, or even shorter. Islamic finance also enjoys benefits of FinTech. Just a quick look at several stories depicts how FinTech is being seen as a significant element that will make a big change in contents of Islamic financial services. Let’s see several stories in these five years.

Given the growing importance of the FinTech, several cities in the Middle East, such as Dubai and Manama, are making efforts to become an Islamic FinTech hub in the world. In the same year, the Islamic Development Bank Group called for business ideas of Islamic FinTech under the project called “FinTech – Islamic Finance Challenge”.

Note that FinTech is a general and collective term and it has many varieties of financial services practiced now. A research firm called Venture Scanner categorized FinTech companies into 13 groups by their businesses: (1) lending, (2) personal finance, (3) payments,

(4) equity financing, (5) remittances, (6) retail investing, (7) institutional investing, (8) security, (9) infrastructure, (10) business tools, (11) Crowdfunding, (12) online banking, and (13) research and data. This implies that we need to look at concrete forms of financial services among various types, when we talk about the actual transaction.

Whatever the terms and the phenomena may be, it is an undisputable fact that the FinTech has already reached the huge continent of Islamic finance.

The 3-step Approach for Socio-economic Development Through Islamic FinTech

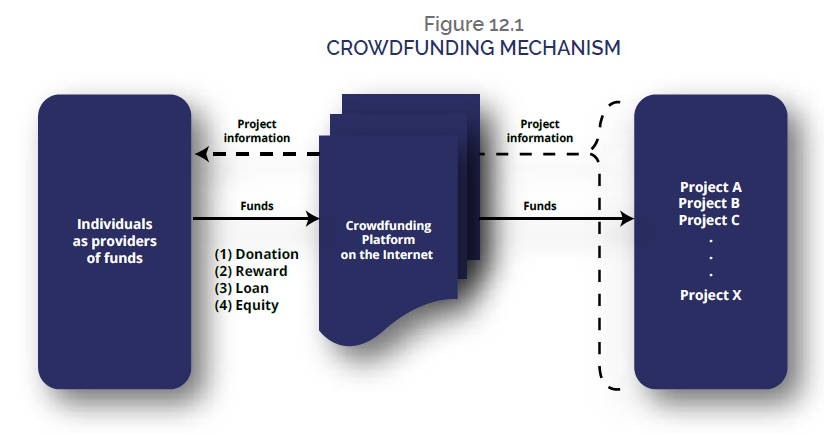

FinTech can help promote financial inclusion and poverty alleviation, from both demand and supply sides of financial services. Before moving on to several forms of Islamic FinTech models for socio-economic development, we should first explain what “crowdfunding” is (Figure 12.1), for better understanding of its application to other Islamic FinTech models.

The modus operandi of the crowdfunding mechanism goes as follows. A platform on the internet provides information on each project to a large number of individuals as potential fund providers – also called a crowd. If an individual decides to provide certain amount of money on the project they would like to financially support, they do so by clicking a relevant button on the website or the smartphone application. The funds are provided typically in four ways: (1) donation, (2) reward (physical products such as manufactured goods), (3) loan, and (4) equity (Massolution 2015). For collection of funds from the public, FinTech can play a huge role with extremely high efficiency of transmitting information and payment from the viewpoint of potential provider of funds.

This crowdfunding mechanism can be applied to financial transactions in Islamically- desirable income redistribution in an economic system. Below, we explore the 3-step approach, depending on the degree of economic development in an economic unit, such as a country or a community. Let’s see how it works.

ICT-enhanced Zakat/Cash Waqf Model

When we talk about social finance in an Islamic context, zakat and waqf should show up on the main stage as a matter of course. Although zakat and waqf are different in nature of willingness to pay, they are part of a traditional income redistribution system in Islam. The following describes how Islamic ICT can be applied to waqf transactions, but the similar can be said to be the case of zakat as well.

Waqf, as one of the traditional methods of income redistribution in Islam, is generally considered as a contribution of asset in the form of real estate or cash, donated by the owner (waaqif) of the asset. The waaqif, in the beginning, specifies an asset (mawquf) for the waqf transaction, with its purpose and the recipients of the benefits (mawquf ‘alayh) and a trustee (mutawalli).

Although waqf transactions were popular in older days such as in the Ottoman Empire periods, they also enjoy modern popularity. It is not just as a practice that was continuously conveyed from the past, but also as an effective financial tool and mechanism that would enhance economic equality in a society, as seen in past works such as Ahmed (2007) and Nagaoka (2013).

Waqf can be theoretically categorized, as a snapshot of its forms in the current practice, by two kinds of dimensions. One dimension is the beneficiary (mawquf ‘alayh); the designated (mu ‘ayyan) or the undesignated (majhul). The other dimension is the nature of the endowed assets (mawquf), real estates or chattels (movables). Amongst these types, traditionally there have been many debates regarding the permissibility under Shari’a, especially regarding cash waqf and family waqf, but this isn’t a focus here. The focus here is set on cash waqf, which is efficiently utilized by the use of ICT, as FinTech.

In this background, FinTech will be able to increase the efficiency of financial transactions in a waqf scheme, and with its increased efficiency, it may be able to create additional values on the waqf transaction. We call this new type as the “FinTech-enabled cash waqf”. As indicated earlier, technologies are utilized in various aspects of financial transactions, so we can expect various forms of expansion of the FinTech-enabled cash waqf.

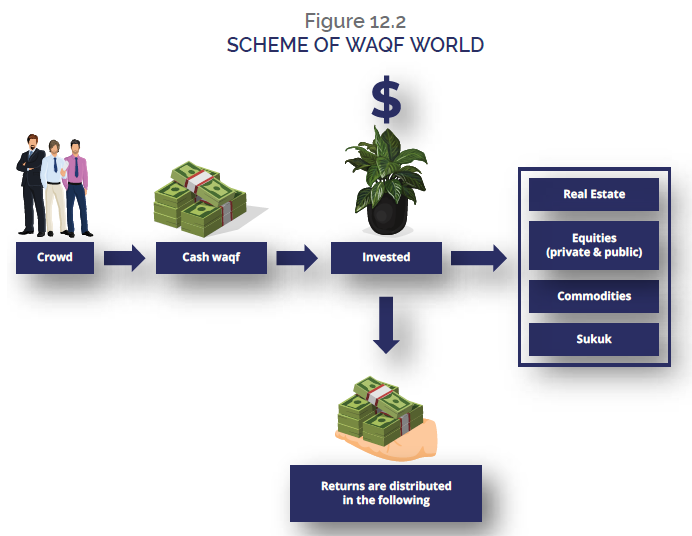

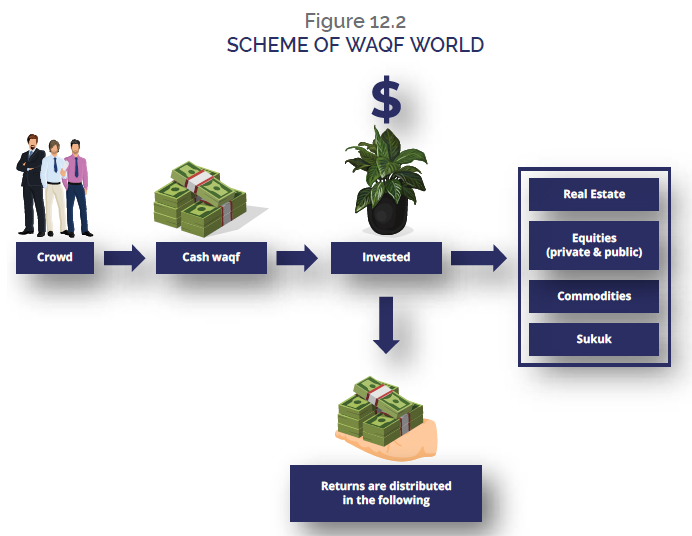

Figure 12.2 shows a basic and good actual case of the FinTech-enabled cash waqf, which is called the “Waqf World”, developed and practiced in Malaysia. The initiative was taken by Tun Abudullah Badawi, ex-Prime Ministry of Malaysia, and it was launched at the 12th World Islamic Economic Forum held in Jakarta in August 2016. The idea was reportedly first presented by Research Center for Islamic Economics and Finance (EKONIS) of National University of Malaysia (UKM) at a forum held by IRTI in January 2016.

Here is the modus operandi of the platform. A potential donator (waaqif) of cash waqf will go to the website of the Waqf World, and provide details of donated amount and the waaqif themselves. The collected funds will be invested into real estates, equities (private & public), commodities, sukuk, to name just a few, in a Shari’a-compliant manner. The profit gained from those investments will be distributed to the people in need, as a typical form of waqf and social finance. Operation of this platform, including technological aspects, is carried out by Ethis Ventures, a local Islamic FinTech venture, which usually offers Islamic equity crowdfunding platform.

ICT-enhanced Islamic Microfinance Model

Microfinance is known as a typical form of social finance since it provides loans to financially challenged people, to which banks seldom provide finance. Considering its nature of financing to the financially challenged, the amount of loan transaction tends to be very small (micro), but the transaction is intended to support small businesses of those people, in the direction of economic independence and getting out of poverty.

Traditionally, microfinance funds come from donations and public endowments such as government, international organizations and NGOs, although recently business-based investment model has also started playing a role. Here, as a more Islamic model of donation, let’s introduce cash waqf funds as source of funds for microfinance activities. This can be called “Microfinance-based dual social finance model” as in Figure 12.3, as a hybrid model of waqf and microfinance.

This model is, not just for those who will benefit from acquiring the microfinance loans, but also for people who must depend on donations from the fund, the source of which is profits generated through the microfinance business using the donated funds. ICT can facilitate collection of cash, and provision of information on microfinance projects for potential waaqif. Also, there can be an automatic system, enhanced by ICT, to transfer a certain portion of the profits to those who are in need.

ICT-enhanced Islamic SME-financing Model

As the next social finance model with Islamic FinTech which is suitable for the third stage of economic development after the one with waqf and the next one with microfinance, we should better put more focus on financing for SMEs. SME financing usually involves the nature of social policy in a government, not just an economic policy that should be based on the nature of capitalism. In an emerging economy, SMEs can be a dynamic source of macroeconomic growth considering its large size and possibility of changing into large corporations to support the whole economy.

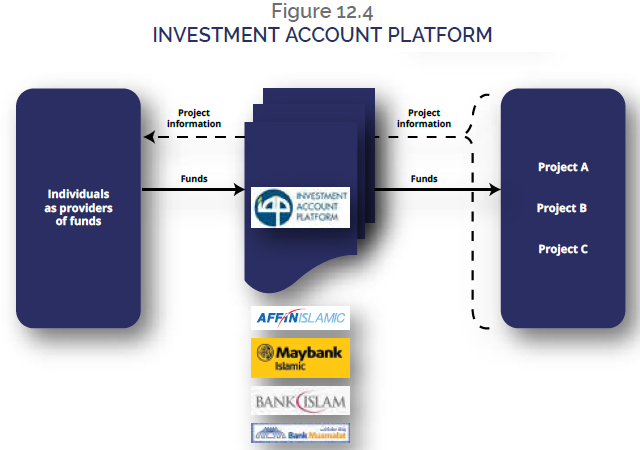

In this context, a good example would be the Investment Account Platform (IAP), led by the initiative of Bank Negara Malaysia. The scheme is shown in Figure 12.4. A quick look will give an impression that this is similar to the form of crowdfunding. Yes, it is exactly crowdfunding. Account holders of participating banks, namely Affin Islamic, Maybank Islamic, Bank Islam, Bank Muamalat, Bank Rakyat, BSN and RHB Islamic, will check the website of IAP, to find good projects to invest into. If they find anything good, they invest their money using their bank accounts. Projects are proposed by companies that are (potential) borrowers of the participating banks, mainly SMEs. This mechanism is expected to contribute to providing funds from Islamic investors, not just out of economic motivations but also with some religious mind to contribute to economic growth of others with lower economic conditions.

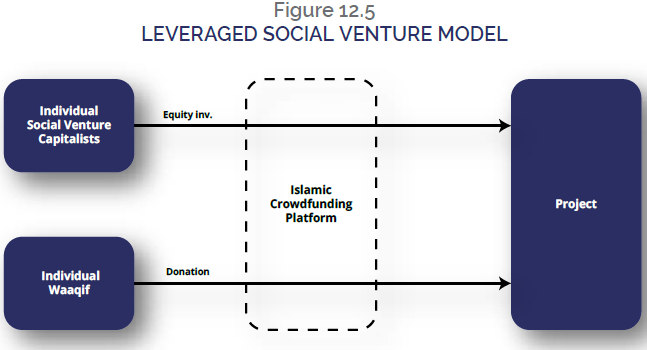

The idea can be developed to a more Islamic model using higher use of ICT. The idea can be called a “leveraged social venture model”, as shown in Figure 12.5. It is a combination of waqf (or could be zakat as well) fund, donation and equity investment for social purposes. Generally, social finance means not just for charity, but can include businesses as well. If a crowdfunding platform opens the door for both social venture capitalists and potential waaqifs, the equity investment for a social business project is leveraged using the collected funds of waqf, in the form of donation, loan, or even equity possibly.

The “Real” Islamic Finance and Prerequisites

Whilst growth of Islamic finance in general is evident not just in its market volume but in product development as well, the industry has often been criticized by academic scholars that the current practice of Islamic finance is not in the direction of pursuing HOS. Rather they think it is just a replica of conventional finance. Now, the industry offers Islamic derivatives, Islamic project finance, Islamic asset management services using highly-sophisticated financial engineering techniques, to name just a few, but the critics are not satisfied with these functions and outcomes of Islamic financial services.

Hasan (2010) criticized that the industry does not care enough about the objective of Islamic finance, and hence, there is a mismatch between structure and objective of the religious economic behaviour. El-Gamal (2003) described the current situation as “Islamic finance quickly turned to mimicking the interest-based conventional finance”. In addition, Hamoudi (2007) called the current situation as “Jurisprudential Schizophrenia” and De Lorenzo (2007) bantered it as “Shari’a-conversio`n technology”. Habib Ahmed (2011) observed the situation in a more objective manner, saying “contemporary practice of Islamic finance has been criticized for not fulfilling the [HOS]”. In addition, Dr Wahbah Al-Zuhayli (2001) says, “the primary goal of Islamic financial institutions is not profit-making, but the endorsement of social goals of socio-economic development and the alleviation of poverty.” Hassan and Lewis (2007) call this situation as the crossroads of Islamic finance.

THE SECOND CALIPH, UMAR, IS CONSIDERED TO HAVE SAID, IF HE WERE TO LIVE LONGER, HE WOULD SEE TO IT THAT EVEN A SHEPHERD ON THE MOUNT SINAI RECEIVED HIS SHARE FROM HIS WEALTH, ACCORDING TO BUKHARI. IN THE CONTEXT OF THE FINTECH-ENABLED CASH WAQF, THE STORY CAN BE INTERPRETED AS FOLLOWS: IF THE CALIPH LIVED LONGER ENOUGH UNTIL THE DAYS WHEN SMARTPHONE WAS AVAILABLE TO EVERYBODY AND DONATION WAS EASILY DONE ON THE PALM, A SHEPHERD IN THE MOUNT SINAI COULD HAVE RECEIVED THE DONATION FROM THE CALIPH LIVING IN MADINA THROUGH THE FINTECH-ENABLED CASH WAQF MECHANISM.

In this context, the potential growth of social finance must be better in terms of HOS, and it is noteworthy that extensive use of ICT can bring financial transactions into that direction. In other words, more “real” Islamic finance will be achieved by further growth of Islamic FinTech. As seen in three steps in the previous section, ICT will enable the crowdfunding mechanism. By connecting potential funds providers and those people with lower income that need funds through crowdfunding mechanism, traditional systems in Islam such as waqf and zakat can function in a more powerful manner and on a larger scale than their old styles. This “networking function” should be emphasised when establishing economic systems in Islamic communities, as the networking capabilities will surely enhance the mobilization of funds towards more financially equal society through income redistribution channels.

FinTech, not limited to Islamic FinTech but including the conventional equivalent in general, has just started its substantial growth, and of course, institutional developments and other arrangements in many aspects will be necessary in order to grow in a sustainable manner. Below are typical preconditions that may be required for growth of ICT-based IsSF mechanisms in many jurisdictions.

Legal Accommodation

One big issue in a jurisdiction will be legal treatment to accommodate Islamic FinTech-based transactions with the existing system. For example, the crowdfunding mechanism in general may be interpreted as fund-raising activities from many and unidentified people, and this may require additional treatments in domestic law. For instance, equity-based crowdfunding deals in the US required legal amendments, because a party that intends to raise funds from the public is required to register with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), with preparing required disclosure documents, under the Securities Act of 1933. The registration with the SEC means continuous disclosure under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Actually, amendment of exemption of these requirements was made, to escape from a lot of regulations intended for transparency and disclosure upon each and every single one of individual investors. More precisely, the government prepared in 2012 a new law called “Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act”, or JOBS Act. The Act has six topics, one of which is about crowdfunding. In this Act, if the fund-raising size is not larger than US$100 million and other conditions are met, a broker (the party that manages crowdfunding platform) is exempted from registration procedures.

It seems the bigger-than-anticipated networking capability of ICT can bring about these issues. There may be many other legal issues when introducing ICT-based social financing transactions.

Shari’a Screening

Needless to say, Shari’a screening will be essential in the introduction of ICT-based IsSF. For example, a developer of a FinTech-enabled cash waqf fund should acquire fatwa (a religious opinion) for the whole transaction in order to avoid ex-post troubles in terms of Shari’a compliance. If the fund manager is not a party from financial industries (e.g., internet technology companies, governmental entities and non-profit organizations), it may be able to consider retaining a third-party consulting firm with the function of a Shari’a board, or it may want to collaborate with financial institutions with expertise of offering Islamic financial services.

Sometimes, absence of Shari’a screening process in recent Islamic crowdfunding firms is reported. However, the waqf-based scheme is solely Islamic and it should be in line with the doctrine. So far, there is no standardized process of Shari’a screening among Islamic FinTech ventures, but hopefully it will be accomplished as they acquire bigger presence in markets in due course.

Public Awareness

Public awareness, or thorough marketing of a key FinTech service such as a crowdfunding platform, will also be an important issue when introducing ICT-based networking tools. If there are not enough people that know and can potentially participate in the scheme, this idea of crowdfunding will not make any sense. One possible solution is that the government shall be an operating body as a catalyst, so that many can be aware of it. Another idea will be that major banks can offer these services using its high creditworthiness and popularity among residents in a country. Leveraging through a major SNS would be a good idea as well.

Security

The more ICT is used in a financial transaction, the bigger the risk of ICT security grows. Every stakeholder must be cautious, while seeking no risk will result in no growth in the business. There is not any easy solution, but it must come along with the FinTech business.

Concluding Remarks

Use of ICT in financial services is expected to create huge changes in the financial industry, and so to Islamic finance as well. Especially, FinTech will reduce the cost related to supply and consumption of financial services, but there is more than that. This chapter focused on networking capabilities realized by high use of ICT and their potential when applied to social finance, especially in terms of religious values of enhancing economic equality in a community. This is exactly the objective of social finance, as well as HOS.

Some readers may think that what is written here may be theoretically right but it can happen only in the future. However, in the ICT industry, some changes can happen in an extremely agile manner. It is very hard to predict the picture of an ICT-based society in even one year ahead, considering very competitive nature of the industry including higher attention to blockchain and AI (artificial intelligence), and the existing giant players such as GAFA, i.e., Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple.

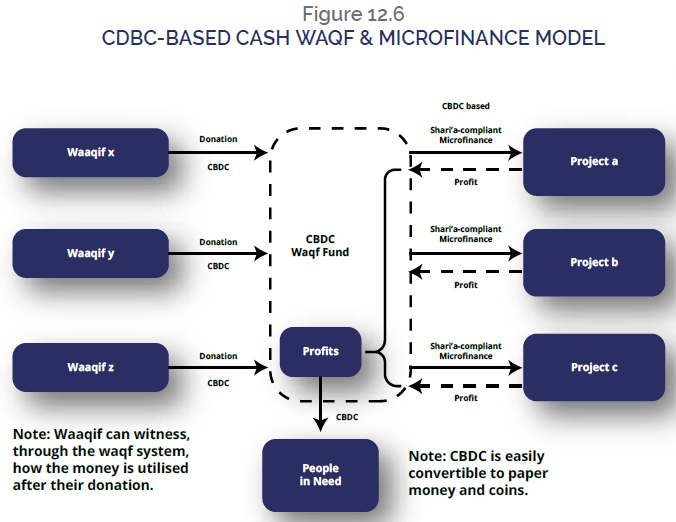

It is not only these huge ICT companies that can provide a big and swift change to a society. The government sector can also be an enabler of the change in recent years. For example, in last several years, cryptocurrencies emerged as an alternative financial asset in markets. Although they are frequently criticized by Islamic scholars for its price volatility and intangible nature, at least the concept has spread all over the world. There are some examples of Shari’a-compliant cryptocurrencies. In addition, it is also true that central banks in Muslim-majority countries such as Saudi Arabia and Kuwait are interested in introducing central bank digital currencies (CBDC), including possibilities of involving blockchain technologies into their banking systems. The CBDC can simply be understood as a state-issued cryptocurrency that has the equal value with the existing national currency.

Once CBDC is introduced in a country, there is high possibilities that economic system in the country can change rapidly. In such an economy, for example, the above-explained model of cash waqf and microfinance can function in a very efficient manner (see Figure 12.6). This also includes transparency of funds from waaqif to projects by establishing appropriate software applications and systems, which is more desirable in terms of Islamic economic ethics.

The second Caliph, Umar, is considered to have said, if he were to live longer, he would see to it that even a shepherd on the Mount Sinai received his share from his wealth, according to Bukhari. In the context of the FinTech-enabled cash waqf, the story can be interpreted as follows: if the Caliph lived long enough until the days when smartphone was available to everybody and donation was easily done on the palm, a shepherd in Mount Sinai could have received the donation from the Caliph living in Madina through the FinTech-enabled cash waqf mechanism.

The voyage with FinTech has just begun. It is a big challenge for the human society whether we can fully utilize the powerful tool for qualitative development of financial system in terms of Shari’a, and more income equality as part of maslaha (public interest), or we just end with having more efficient financial transactions.