A Possible Existential Crises

Introduction

Most countries of the world have committed to achieving the sustainable developmental goals (SDGs) launched by the United Nations in 2015, that envision a balanced, equitable and environment-friendly growth path.

The efforts of these countries’ progression towards sustainable development are in the backdrop of an increasingly digitalised world, an impending climate crisis and compounded global risks and uncertainties.

One way of categorising risks facing businesses in general and financial institutions in particular, is exogenous and endogenous. Exogenous risks arise from factors that are external to financial institutions such as macroeconomic factors, environmental risks, legal and regulatory changes, geopolitical and societal risks, etc.

Endogenous risks arise within an organisation, and can be broadly classified as strategic risks and operational risks. While strategic risks relate to long-term issues that affect the growth and performance of an organisation, operational risks arise in implementing the strategy in the short- term.

Strategic risk management requires understanding the long-term risks and then developing appropriate policies and plans to navigate the future to achieve the long-term objectives of the organisation.

While strategic risk management would mainly deal with long-term endogenous risks, it is also influenced by and includes plans to mitigate exogenous risks. Although organisations do not have direct control over exogenous risks, they can take steps to minimise their impact and cope with them by building resilient structures and systems. Operational risk management would involve instituting appropriate risk management systems to mitigate various risks that organisations face in their day-to-day operations.

This paper focuses on strategic risks that the Islamic financial industry faces, and discusses how these could affect the future trajectory of the industry. The risks that the Islamic financial sector faces can be broadly classified into two types.

First are risks that are common to both Islamic and conventional financial sectors, while the second type of risks are unique to Islamic finance.

The paper first presents the evolving uncertainties and risk environment under which both Islamic and conventional financial industry are expected to operate in the future. It then identifies the risks that are unique to Islamic finance. A key risk relating to the very essence of Islamic finance which is of existential nature is highlighted. After discussing how conventional financial sector is dealing with the strategic risks, the paper presents some suggestions on how Islamic finance can take strategic decisions to mitigate the risks and prosper in the future.

Future Risks and the Financial Sector

The economies of the world are facing a variety of risks arising from different sources. In line with WEF (2022), the sources of risks can be categorised as economic, environmental, legal/ regulatory and geopolitical, societal and technological.

Table 8.1 reports the top future risks identified in the following three recent surveys of key stakeholders: WEF (2022) survey of 12,000 country-level leaders identifying the most severe risks at the global scale during the next 10 years; Allianz (2022) survey of 2,650 risk management experts from 89 countries across 22 industry sectors; and Protiviti (2021) survey of 1,081 global board members and C-suite executives on key risks in 2030.

While all risks listed in Table 8.1 are relevant, a few key risks that will shape the future of financial industry are economic, environment and technological. Beyond the impact of global uncertainties on national economies and financial systems, a strategic economic concern that the financial sector needs to deal with would be demographic shifts that will change the preferences and demand from future customers.

Table 8.1 Top Risks in the Future – Survey Results

| Risk Category | Top Risks |

| Economic | WEF Top Risks (10 Years): Debt crisis; price instability; energy security; commodity shocks |

| Allianz Survey: Business interruptions (supply chain issues; market developments; shortage of skilled workforce; macroeconomic factors (inflation, monetary policies, etc.) Protiviti &Top Risks (2030): Attract and retain top talent; substitute products and services; demographic shifts and customer preferences | |

| Environmental | WEF Top Risks (10 Years): Climate action failure; extreme weather; biodiversity loss; human environmental damage; natural resource crisis Allianz Survey: Natural catastrophes; Climate change; fire explosion |

| Legal/Regulatory and Geopolitical | WEF Top Risks (10 Years): Geo-economic confrontation Allianz Survey: Changes in legislation and regulation Protiviti &Top Risks (2030): Regulatory changes |

| Societal | WEF Top Risks (10 Years): Social cohesion erosion; livelihood crisis; infectious diseases Allianz Survey: Pandemic outbreak |

| WEF Top Risks (10 Years): Cybersecurity; digital inequality Allianz Survey: Cyber incidents Protiviti &Top Risks (2030): New skills for digital technology adoption; disruptive innovations; Information security; competition from digital providers; unable to use data analytics and big data |

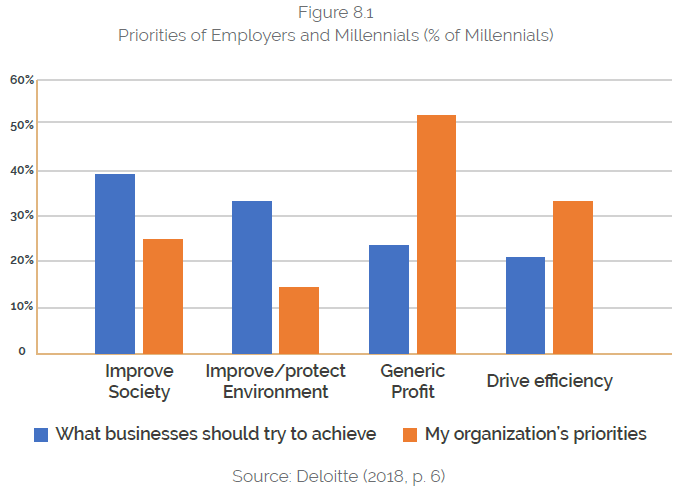

Results from a Deloitte (2018) survey of 10,455 millennials and 1,844 Gen Z respondents from 36 countries show that significant proportions of millennials (83%) and of Gen Z (80%) feel that business success should be measured by things that go beyond financial performance.

Some key results from the survey shown in Figure 8.1 indicate a mismatch of their priorities and those of their current employers. While a larger percentage of millennials and Gen Z feel that businesses should play a role in improving society (39%) and environment (33%) compared to their employers (25% and 14% respectively), the organisations prioritise profit (51%) and efficiency (33%) in higher numbers than them (24% and 21% respectively).

From a strategic point of view, the preferences of the millenniums and Gen Z would represent expectations and trends of the future demand, and businesses and financial institutions have to pay attention to their needs and preferences.

The second crucial risk relates to climate crisis and environmental degradation that the global community has to deal with collectively and everyone has to do their part. As in the case of many businesses, many financial institutions are moving towards improving the environment, social and governance (ESG) performances partly due to expectations from the stakeholders.

One way of doing this is to incorporate ESG risk mitigation in their operations and financing/ investment activities. Final important risk arises from adapting business models to rapid changes in digital technologies.

The financial sector has to adopt digital technologies or will face the risk of being disrupted by new savvy and dynamic FinTechs that can provide services more efficiently and at a faster pace. This would require the right talent and skilled workforce who can deliver the products and services in increasingly digitalised markets.

Islamic Finance and Unique Existential Risk

The distinctiveness of Islamic finance lies in the prefix ‘Islamic’ that gives its identity and meaning. The ‘Islamic’ feature is manifested by compliance with Shari’a principles and values. A unique risk that Islamic finance faces relates to how ‘Shari’a compliance’ is defined and what it means to different stakeholders. In particular, Shari’a compliance can be interpreted in narrow or broad terms. While the narrow meaning of Shari’a compliance focuses on formal legal compliance with Shari’a rules in a mechanical way, the broader interpretation includes complying with the Shari’a rules and ethical values expressed in the OS.

At a broader level, the essence of maqasid can be summarised by the maxim stating that the overall goal of the Islamic law is the ‘promotion of welfare or benefits and prevention of harm’ (jalb al-masalih wa-dar’ al mafasid) (Dien 2004, Kamali 2008). More specifically, the essential goals or maqasid of Shari’a are identified as protection and enhancement of the faith, self, intellect, posterity, and wealth (Hallaq 2004, Kamali 2003).

Ibn Ashur (2006) identifies five further maqasid-al-Shari’a related to economic activities and transactions as circulation, preservation, persistence, transparency and justice. The maqasid perspective goes beyond legal compliance in contracts and considers the outcome and impact of transactions.

Different meanings of Shari’a compliance have implications for business models, products and markets served. For example, a narrow view of Shari’a compliance focussing on legality of contracts has resulted in shareholders’ value maximisation model in Islamic financial institutions.

Operationally, this has resulted in a business model of replicating conventional financial products through reverse engineering that are sold in market segments where most profit is reaped in a secure manner. Alternatively, using broader perspective of Shari’a would lead to a stakeholder’s model that would include economic and social value creation as organisational objectives and using inclusive Shari’a-based products serving all market segments.

There seems to be a mismatch of the notions of Shari’a compliance between the customers, who form key stakeholders and Islamic financial institutions. A large percentage of Muslims engage with Islamic finance due to religious convictions and to fulfil Shari’a commandments related to economic transactions. Shari’a compliance for them, means not only avoiding riba, but also fulfilling ethical and social goals.

This is apparent from a survey of 477 respondents carried out in Malaysia (see left-hand side of Table 8.2). On a scale of 1 to 5 (with 1 representing ‘Not important’ and 5 indicating ‘Very important’), the highest-ranking expectations of the stakeholders for Islamic finance are providing Shari’a-compliant products (average score of 4.60), promoting sustainable development’ (score of 4.13) and contributing to social welfare (score of 4.07). The respondents rank ‘maximising profits’ below these objectives with a score of 3.76.

A survey regarding the concerns of CEOs of Islamic banks, however, shows different preferences. Right-hand side of Table 8.2 shows that the top-most concern of 103 CEO’s is ‘Shareholders’ Value & Expectations (score of 4.35).

Table 8.2 Stakeholders’ Objectives and Concerns of Islamic Financial Institutions

| Stakeholders’ Expectationsa (477 respondents in Malaysia) | Islamic Banks Concernsb (103 CEOs from 31 Countries) | ||

| Objectives | Score* | Concerns | Score* (Rank) |

| Provide Shari’a-compliant products | 4.60 | Shareholders’ Value & Expectations | 4.35 (1) |

| Promote sustainable development | 4.13 | Consumer Attraction, Relation & Retention | 4.26 (6) |

| Contribute to social welfare | 4.07 | Shari’a standards, compliance and governance framework | 4.16 (8) |

| Maximising profits | 3.76 | Financial Inclusion, Micro & SME Financing | 3.67 (18) |

Interestingly, ‘Shari’a standards, compliance and governance framework’ is ranked as 8th concern with a score of 4.16. Social and development-related issues reflected in ‘Financial Inclusion, Micro & SME Financing’ has a score of 3.67 and is ranked much lower at 18th position. The low priority for social and developmental issues is also apparent in several empirical studies, that show insignificant contribution of Islamic banks towards social and environmental impact (see for example Aribi and Arun 2012, Haniffa and Hudaib 2007, Kamla and Rammal 2013, Maali at al. 2006).

Evidence from surveys clearly shows a disparity in the understanding of the notions of Shari’a compliance between the customers and Islamic financial institutions. The differences in stakeholder expectations and practice can have a negative impact on the customers’ perceptions regarding Islamic banking operations. For example, in a survey of 146 respondents in the UK, Rahman (2012) finds that 78.2% agree or strongly agree with the statement, ‘Muslims believe that Islamic banking is just change of names.’ The numbers are 73.9% for the statement, ‘Muslims have doubts about the banking products of IsFIs’ and 65.7% for the statement, ‘Islamic financial institutions are not meeting the financial needs of Muslims.’

While it is likely that part of the problem with the responses in the above survey may be due to the lack knowledge of Islamic financial products, but the evidence of the expectations of stakeholders points out to a serious existential risk for Islamic finance. From a strategic risk perspective, divergence of meanings of Shari’a compliance among different stakeholders can impact the reputation and have implications on the essence and future of Islamic finance. Not only is this an issue of reputational risk, but more importantly, it is about erosion of ‘trust’ that people have on the industry. The lack of trust and credibility can impact the growth of the industry in the future since these ethical notions are fundamental to economic and financial relationships and transactions.

Common Risks, Conventional and Islamic Finance

Financial institutions have to think strategically on how to align their operations to deal with the numerous risks that economies are facing, which are expected to become more acute in the future.

To stay relevant and survive in an uncertain environment, financial institutions have to cope with the key economic, environmental and technological risks and positively contribute to the SDGs. As implied in the Deloitte survey of millennials and Gen Z presented in Figure 8.1, the future market trends are expected to move from focussing on profits only to include societal and environmental concerns. This would require moving from the current shareholders’ model towards a stakeholders’ model that have triple bottom lines of profit, people and planet. Since the Islamic financial industry also faces these common risks, there is a need to strategically realign their business model from the one that focuses on maximising the shareholders’ values only to that of the stakeholders’ model.

Furthermore, the adoption of digital technology will be crucial for financial institutions to remain competitive and achieve the future organisational goals more efficiently and effectively.

Responding to the future market expectations and trends, many businesses and financial institutions in the West are making strategic decisions to transform organisational orientation to meet the needs of the society and mitigate environmental risks. Many corporations are conscious about the broader ‘purposes’ beyond maximising shareholders value and considering ESG related issues in decision-making. This is evident from the ‘Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation’ issued by 181 top US CEOs (representing 30% of US market capitalisation) in 2019. The statement states that “Each of our stakeholders is essential. We commit to deliver value to all of them, for the future success of our companies, our communities and our country.”

The trend is also seen in the conventional financial industry where a significant percentage of investments are going into sustainable assets. For example, in 2020, the proportion of sustainable investments to total managed assets was 61.8% in Canada, 41.6% in Europe, 37.9% in Australasia and 33.2% in United States (GSI 2021). A specific example of the re-alignment of organisational purpose comes from Blackrock, the largest asset management company in the world (managing US$10.01 trillion assets in 2021 compared to a total of less than US$3 trillion Islamic finance assets). Larry Fink, CEO and Chairman of Blackrock in his 2019 annual letter to CEOs of companies entitled “Profit & Purpose” asserted that “Society is increasingly looking to companies; both public and private, to address pressing social and economic issues” and “Companies that fulfil their purpose and responsibilities to stakeholders reap rewards over the long-term. Companies that ignore them stumble and fail.” Similarly, in his 2020 annual CEO letter entitled “A Fundamental Reshaping of Finance” Fink declared that sustainability would be at the centre of Blackrock’s investment approach. He emphasised that the company would make “sustainability integral to portfolio construction and risk management” and “there will be a significant reallocation of capital”.

While no specific data on the contribution of Islamic financial institutions towards sustainable investments is available, the evidence presented above indicates that their inclination to contribute towards social and environmental areas is minimal. From a strategic point of view, the failure of the Islamic financial institutions to address these major emerging risks could seriously affect their viability in the longer term. Not addressing the ESG risks would imply that Islamic financial institutions could ‘stumble and fail’ and hamper the future growth of the industry.

Islamic Finance and Risks: The Way Forward

The current practice of Islamic finance adopting a narrow legalistic interpretation of Shari’a compliance is not aligned with the broader goals of Shari’a and is contrary to the expectations of the stakeholders. While the values of maqasid points to adopting inclusive and sustainable finance, using the narrow legalistic Shari’a perspective has led Islamic finance to ignoring these issues. As indicated above, from a strategic point of view, disregarding the environmental and societal issues can be disastrous for the future viability of Islamic finance, both in terms of mitigating economic and environmental risks, and also from the perspective of existential risk related to mismatch of meanings of Shari’a compliance. To be viable in the future, Islamic financial industry needs to integrate ESG, technology and finance to sustain their operations in risky environments.

Many stakeholders view Shari’a compliance form a broader maqasid perspective as revealed in the survey results reported in Table 8.2. Looking forward, many Muslim millennials and Gen Z, who would be future prospective customers share the priorities of focussing on societal and environmental issues, as the Deloitte survey shows in Figure 8.1.4 They would expect Islamic financial institutions to contribute to social and developmental issues as is being done in conventional finance. The practice of focusing on narrow legalistic Shari’a compliance and ignoring the maqasid could be interpreted as Islamic finance not fulfilling the broader Shari’a values. The divergence of the meaning of Shari’a compliance can affect industry’s reputation and credibility (as seen in the UK survey) and pose existential risk. One can ponder whether the lack of trust and credibility are playing a role in the slowdown of the growth rates of the Islamic finance industry from double digits in the past to single digits during recent times.

To be relevant in the future, there would be a need to adopt the broader meaning of Shari’a compliance that incorporates maqasid-al-Shari’a and realigns the operations of the industry accordingly. Incidentally, embracing the broader Shari’a compliance concept to include maqasid will also help align operations of the industry to one that can deal with the common economic and environmental risks discussed above. Adopting the broader notion of Shari’a compliance would imply changing from the current narrow shareholder’s model to the stakeholders’ model that creates both economic and social values.

Including ethical values of the maqasid will translate into incorporating ESG-related issues in decision making which will result in more inclusive and sustainable financing. This will not only build back the trust, credibility and reputation of Islamic finance among the stakeholders but also enhance the industry’s resilience and contribution to the SDGs. Strategically, implementing maqasid as part of broader meaning of Shari’a compliance is essential for ensuring long-term growth of the industry and making Islamic finance relevant in the future.