Continued Innovation For Market Relevance And Future Growth

Introduction

Like its conventional counterpart, the Islamic finance sector has had to withstand numerous challenges over the years, most recently, the on-going economic and social implications of the COVID-19 pandemic. At the same time, the sector has and continues to face questions as to whether it complies with Islamic law in substance, or only in form, and whether it has disengaged from its inherent ethical framework and religious underpinnings.

Despite these challenges, the Islamic finance industry has continued to expand and mature in the last decade, with new market participants and products entering the market. Islamic finance is now an established sector in the global financial market, both within and outside of the Muslim-majority countries. But this successful cultivation of an established Islamic finance sector is not now a basis for complacency. If the Islamic finance sector is to remain relevant, and ensure its long-term sustainability, there must be a willingness to innovate and respond to broader market developments.

Innovation within Islamic finance is, however, more challenging and nuanced than it is in the conventional sector. Not only must new products and transactions be financially viable and structurally possible within existing regulatory frameworks, but they must also be compatible with the financial principles of the Islamic law.

This chapter will consider two innovative products in the global financial market – (1) social and sustainability capital markets instruments and (2) cryptocurrencies. One of these products conceptually aligns well with the financial principles of Islamic law and has been readily accepted by the Islamic finance market, the other has not. This chapter will, therefore, discuss whether these products have been localised into the Islamic finance market, the structures developed for these products within Islamic finance, and difficulties that have been faced by those seeking to introduce these new products. This chapter does not cover every recent innovation that might be relevant to the Islamic finance industry. Instead it seeks to provide a snapshot of some of the more high-profile ways in which those within the Islamic finance industry are seeking to maintain its relevance and ongoing sustainability, as well as difficulties faced by the industry when trying to come to a consensus on a new product.

Social and Sustainability Sukuk

Steady growth of the responsible finance bond and sukuk markets

A growing global focus on environmental, social and sustainability issues has led to increased attention in the conventional finance sector on the use of responsible finance products to help finance a response to those issues. These products have included green loans, investment funds guided by sustainability criteria, and the issuance of capital markets instruments – including bonds – with clear green, social or sustainability objectives. In the capital markets space, ‘responsible finance bonds’ are structured to consider both financial and non-financial criteria, such that they target financial returns and the maximisation of societal value. As such, responsible finance bonds are structured such that the proceeds generated by the issue of the bonds are directed towards the financing or refinancing of green and/or social projects. Within the Islamic finance market, responsible finance products and transactions have also gained momentum, supported by governments, market participants and industry bodies. The Islamic Development Bank, for example, has noted that the ‘aspirations for human dignity, and “to leave no one behind”’ within the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Sustainable Development Goals (the SDGs) are ‘fully in line with the principles and objectives of development from an Islamic perspective’. The bank went on to highlight the significant funding requirements needed to meet the SDGs and the potential use of Islamic finance as a vehicle for providing that funding. AAOIFI has also encouraged Islamic finance institutions to pursue investments that contribute directly or indirectly to ‘social, development and environmental causes.’

To date, the sustainability discussion in a finance context has predominantly focused on environmental and climate-related concerns. This has led to a steady growth over the last five years in the number of issuances of green bonds with environmental objectives – such as those that have funded the construction of solar power plants or green transportation projects. Though coming sometime after the conventional industry’s entrance into the green bond market, the Islamic finance industry has also embraced this product innovation. This has led to the development of shari’a-compliant alternatives to green bonds, in the form of green sukuk. These green sukuk are structurally similar to standard sukuk, but they are designed to intentionally direct the issue proceeds towards the financing or refinancing of eligible green projects.

A new focus on social and sustainability considerations – a slower start for sukuk?

More recently, the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, and its impact on health, society and economies, has acted as a catalyst for a rapid increase in the number of social and sustainability bond issuances in 2020 and 2021. Social bonds are financial instruments that are structured so that the proceeds generated from the issue of the bonds are intentionally used to fund new and existing social projects – such as access to essential services, employment generation and socioeconomic advancement and empowerment. The proceeds generated from an issue of sustainability bonds are directed towards funding projects that combine both social and green objectives. The risk-return profile of social and sustainability bonds is comparable to that of standard bonds. Yet there is an articulated intentionality of social purpose underpinning an issue of social or sustainability bonds that is disclosed to investors when these instruments are issued and the fulfilment of which is often reported on following an issuance.

2020 and 2021 also saw an increase in interest with respect to social and sustainability sukuk, targeting social issues. Yet, despite additional attention, the number of issuances of such sukuk has remained comparatively small and the market has not yet experienced the surge in issuances seen in the conventional social and sustainability bond sector. In practice, social and sustainability sukuk are more complex and take longer to issue than their conventional equivalents. They require not only evidence of a valid social framework through which social projects can be identified and managed, but also confirmation of the issuance’s compliance with the financial principles of Islamic law.

Malaysian Sustainability Sukuk – indications of market interest

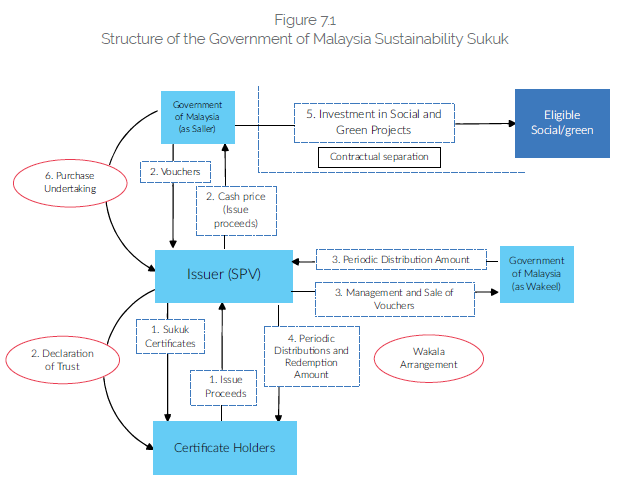

Nevertheless, we are now starting to see a willingness within the Islamic finance industry to innovate and respond to wider market interest in social and sustainability capital markets products. In April 2021, for example, the Government of Malaysia through a special purpose vehicle (an SPV – Malaysia Wakala Sukuk Berhad) issued the world’s first USD-denominated sovereign sustainability sukuk with the issue of USD800,000,000 worth of sustainability sukuk certificates due 2031 (the Malaysian Sustainability Sukuk). At the same time, the Government of Malaysia undertook a parallel issuance of USD500,000,000 worth of standard sukuk certificates, bringing the total issuance to USD1.3 billion. (See Figure 7.1 for the structure of sukuk).

The issuance was based on a wakala agency arrangement as the underpinning contractual structure. As part of the issuance of the Malaysian Sustainability Sukuk, therefore, the issuer agreed to apply 100 per cent of the Malaysian Sustainability Sukuk issue proceeds towards the purchase of certain vouchers from the Government of Malaysia. These vouchers represented an entitlement to a specified number of travel units on Malaysia’s Light Rail Transit, Mass Rapid Transit and KL Monorail networks. The issuer (as trustee) declared a trust in favour of certificate- holders over all of its rights, title, interest and benefit in and to the vouchers, the related transaction documents, cash standing in certain accounts and connected proceeds. This gave certificate-holders an undivided beneficial ownership interest in, and the right to receive certain payments arising from, the sale of the vouchers. While (in common with other responsible finance sukuk) this did not give the certificate-holders an ownership interest in the social and green projects ultimately to be funded through the issue of the Malaysian Sustainability Sukuk, this sukuk issuance is unusual amongst other responsible finance sukuk in the market. Typically, certificate- holders are given a beneficial ownership interest in various tangible and intangible assets with no obvious sustainability characteristics. In the case of the Malaysian Sustainability Sukuk, the vouchers represent travel units on Malaysia’s public transport network, something that arguably displays inherent green and social characteristics. With the cash paid to it from the sale of the vouchers to the issuer, the Government of Malaysia will receive upfront payment of an amount equivalent to the full issue proceeds that it will then use to finance or refinance expenditure relating to eligible social and/or green projects.

Pursuant to a wakala agreement between the issuer SPV and the Government of Malaysia, the Government was appointed as agent (or wakeel) of the issuer to periodically sell the vouchers to public transport customers and then to pay the issuer an amount reflecting the sale proceeds. These proceeds will be used to pay periodic distribution amounts to certificate holders. This structure will give those certificate-holders the regular payments of profit due under the sukuk documentation. At maturity or early redemption of the Malaysian Sustainability Sukuk, the Government of Malaysia has undertaken to repurchase from the issuer any unsold vouchers at a price equal to the outstanding face amount of the sukuk certificates, plus any unpaid periodic distribution amount. This amount will be used by the issuer SPV to repay certificateholders their capital investment in the Malaysian Sustainability Sukuk, and to redeem any outstanding sukuk in full.

Periodic payments to certificate-holders during the life of the Malaysian Sustainability Sukuk, and the amounts used to repay certificate-holders upon redemption of these sukuk are, therefore, generated not by a separate social and/or green project funded by the Government of Malaysia, but rather by the purchase and sale of travel vouchers. Nevertheless, the use of the proceeds section of the Malaysian Sustainability Sukuk Offering Memorandum clearly outlines a sustainability basis for how the proceeds generated by the issue of the sukuk will ultimately be used to fund social and green projects by the Government of Malaysia. It therefore notes that ‘the net proceeds… received by the Government of Malaysia in connection with the sale of the Vouchers will be used by the Government of Malaysia for Shari’a compliant general purposes, including but not limited, to financing or refinancing, in whole or in part, new or existing development expenditure with a social and/or green focus, in accordance with the eligibility criteria described under the SDG Sukuk Framework of the Government of Malaysia’. This SDG Sukuk Framework (the Framework) is part of the Government of Malaysia’s broader sustainability ambitions and goes on to emphasise that sustainability sukuk will be used by the Government to ‘fund projects that will deliver environmental and social benefits which are in close alignment with the SDGs’. Eligible projects include those targeting access to quality healthcare – such as building and/or upgrading hospitals, clinics and healthcare facilities; projects designed to increase accessibility to affordable and quality basic infrastructure – such as improving efficiency of broadband infrastructure in rural areas; and projects to develop clean public transport systems. The framework explicitly excludes expenditure in a number of industries, including those involved in weapons and military contracting, adult entertainment, alcohol and tobacco, and fossil-fuel-related activities.

Following the issue of sukuk under the Framework, the Government of Malaysia will report annually on the allocation of the issue proceeds, the projects funded and, where possible, the social and environmental impacts associated with the funding (such as number of hospitals built, number of women supported, and annual greenhouse gas emissions reduced). It also engaged Sustainalytics (an independent environmental, social and governance assessment firm) to carry out a pre-issuance review of the Framework and has agreed to engage an independent third party to review the Government of Malaysia’s annual sustainability reports. As part of its evaluation, Sustainalytics noted that it was confident that the Government of Malaysia was ‘well-positioned to issue sustainability bonds [and sukuk]’ and that its ‘SDG Sukuk Framework is robust, transparent, and in alignment with the Green Bond Principles (2018) and Social Bond Principles (2020) and ASEAN Sustainability Bond Standards.’ While noting that the Government of Malaysia’s sustainability targets could lead to ‘negative environmental and social outcomes’, Sustainalytics concluded that the Government was in a position to manage and/or mitigate these potential risks.

Looking to the future

The Malaysian Sustainability Sukuk issuance was oversubscribed, with an investor base from across Asia, Europe, and the United States. There is an appetite for sukuk structured to fund not just green projects, but also projects focused on social goals aiming to create a positive social impact. It is imperative that the industry responds to this enthusiasm. A failure to do so could leave sukuk investors with fewer social and sustainability investment opportunities, and could also impact the longer-term societal benefits coming from the targeted investments of social and sustainability sukuk issue proceeds. Reflecting this opportunity, key market players are beginning to engage with the social and sustainability sukuk market – in March 2021, the Islamic Development Bank issued USD2.5 billion worth of sustainability sukuk, following a USD1.5 billion sustainability sukuk issuance the year before. Within sukuk hubs such as Malaysia, there have also been a number of domestic sustainability sukuk issuances by corporate issuers. We are yet to see more consistent issuances of social and sustainability sukuk in the international markets. But with the emergence of benchmark offerings, such as the Malaysian Sustainability Sukuk and the issuance of sustainability sukuk by the Islamic Development Bank, the market now has precedents that can be used as a springboard for future issuances by corporates and other sovereigns looking to fund socially positive projects.

The spread of COVID-19 infections around the world in 2020, 2021 and the continued impact of the virus into 2022 has required states, multilateral agencies, and the private sector to respond decisively. It also mobilised the financial market to consider how the capital markets could be used to address these and other social issues. Social and sustainability sukuk offer issuers a mechanism for raising capital to invest in projects with specific social objectives; at the same time, they give investors a way of funding social projects while still earning a return. As a way of tackling pressing social issues, these financial instruments would also appear to align well with the broader ethical and developmental goals of Islam. As a financially viable way of tackling broader social issues, social and sustainability sukuk offer an important basis for ongoing resilience and sustainability of the industry.

Cryptocurrencies and Islamic Finance

Issuances of social and sustainability sukuk have emerged over the last few years, encouraged largely by consistent support of the market, industry bodies and governments. However, not every product innovation within Islamic finance has seen so much support. The Islamic finance industry continues to have a more uneasy relationship with cryptocurrencies, compounded by conflicting views as to the nature and religious legitimacy of crypto-assets and cryptocurrencies across the industry. This is not wholly surprising – it is a highly complex sector that is developing rapidly, with limited regulatory oversight. Yet crypto-based transactions stand as a very clear example of the added tensions faced by innovation in the Islamic finance market where not only must innovators seek to operate within the existing regulatory framework, but they must also provide assurances as to the religious compatibility of their product or transaction. Nevertheless, in December 2020, a World Economic Forum report stated that ‘cryptocurrencies have reached a point of inevitability’; they are becoming an increasingly pervasive aspect of global financial activity, and one that the Islamic finance industry must not just ignore.

There have been some moves to develop specifically Islamic crypto-assets and cryptocurrencies. For example, Islamic Coin has been marketed as ‘Shari’a-compliant digital money’ built on a dedicated Islamic Blockchain. Islamic Coins are ‘minted’ by ‘those who contribute work and investment’ and with each newly minted Islamic Coin, 10% of the issued amount is deposited in a decentralised autonomous organisation for future investment into Islamic internet projects or for donation to Islamic charities. $MRHB describes itself as an ‘ethical cryptocurrency’ – as a utility token it provides holders with certain discounts, access to products and services within the MRHB Defi network and will ultimately ‘serve as a payment token within the system for certain services and features’. CaizCoin has marketed itself as ‘the first Islamic compliant cryptocurrency’ which will ‘revolutionize the concept of virtual currency based on goodness and faithfulness’ providing for investing and purchase options within the Caiz network.

The difficulty from an Islamic finance perspective with engagement with cryptocurrencies is that there is little consistency in terms of how religious scholars, governments and market participants approach the religious legitimacy of cryptocurrencies. There are scholars and authorities that confirm that cryptocurrency is not inherently haram, while others prohibit engagement with cryptocurrencies on the basis that they do not comply with Islamic law. The Shariyah Review Bureau in Bahrain, for example, has noted that ‘Bitcoin has a lawful and Shari’a compliant utility, which is to function as a medium of exchange, facilitate payment and the transfer of value; as such Bitcoin is Shari’a compliant. On the other hand, the National Ulema Council in Indonesia has deemed the use of cryptocurrencies as a currency to be haram and forbidden (although if a cryptocurrency is a commodity or asset that fulfils the requirements of Shari’a, is underpinned by something, and has clear benefits, then it can be legally traded).

Inconsistency of opinion is nothing new to the Islamic finance industry, but the variety of opinions when it comes to cryptocurrencies and the absence of clear guiding views could make it difficult for the industry to effectively respond to the growing cryptocurrency sector. This could lead to a reluctance of market participants to get involved with cryptocurrency-related transactions, or could encourage the use of cryptocurrencies in a way that claims to be religiously compatible, but which is in fact inconsistent with the financial principles of Islamic law.

Much of the literature on Islamic finance and cryptocurrencies directly deals with whether cryptocurrencies are halal or haram. However, when engaging with an innovative product like cryptocurrencies, it is important that the industry takes a step back, and attempts to reach a common ground (as far as one is possible) on what cryptocurrencies actually are – money, assets, or a hybrid of the two? There is a fundamental issue here that is often overlooked in literature on Islamic finance and cryptocurrencies, which is the legal nature of those cryptocurrencies. This chapter will not answer the question of cryptocurrencies’ legal nature. It will explore relevant definitions as well as the guidance set by recent regulatory statements and court decisions in the conventional sector, which each seek to clarify the nature of cryptocurrencies. It will also call on those within the industry, particularly standard-setting bodies, to seek to reach a common understanding of the legal nature of some of the more commonly used cryptocurrencies. This chapter focuses on Bitcoins, as the most pervasive form of cryptocurrency.

Cryptocurrency – Money or Asset?

Cryptocurrencies come with much of the terminology of traditional money. How a cryptocurrency is to be legally classified remains a key question across the cryptocurrency market. Some in the conventional sector have queried whether cryptocurrencies possess the attributes of money: (1) unit of account (money is used as a benchmark for measuring the value of other things); (2) medium of exchange (money is used to enable the purchase and sale of things between parties); and (3) store of value (money’s value can be stored and used at a later date). When a thing starts to perform these functions, historically the courts and authorities have tended to recognise that thing as money. In the conventional sector, there have been some indications that certain cryptocurrencies may have assumed the characteristics of money. In United States v Ulbricht, for example, the court found that ‘Bitcoins carry value – that is their purpose and function – and act as a medium of exchange.

However, in practice, it is not quite so clearcut. Former Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney noted that cryptocurrencies fail to fulfil the three characteristics of money, noting that they do not function well as a store of value (being highly volatile in price), they are rarely used as a means of payment, and they are not generally used as a unit of account. Even Bitcoin, as the most widely used form of cryptocurrency, is only used as payment in a tiny percentage of daily transactions globally. The prices of cryptocurrencies highlight the volatile nature of this market and the difficulties that it is likely to face in its push for mainstream market access. Reflecting this, ‘cryptocurrencies act as money, at best, only for some people and to a limited extent, and even then only in parallel with the traditional currencies of the users.’ From an Islamic perspective, the primary sources of Islamic law have not outlined a definition of money, or the characteristics of what might be described as money. Instead, the Qur’an and Sunnah make reference to the types of money already in existence at the time of the Prophet Mohammed, most notably, the Dinar (gold coins) and Dirham (silver coins). This absence of guidance on the required characteristics of money in Islamic law was confirmed by classical scholars writing in the area, a number of whom sought to clarify a meaning of money themselves. Imam Abu Hanifa writing comparatively shortly after the time of the Prophet Mohammed, for example, noted that gold and silver are money by nature, whereas fulus (copper coins) is money simply as a result of its adoption and acceptance as such by the community. Ibn Taymiyyah acknowledged that Islam has not provided a definition of money, but has instead left this decision as to what is and is not money up to custom (‘urf) of the people. Ibn Taymiyyah himself suggested that there are two main functions of money – as a measure of value and as a medium of exchange. With a move away from gold and silver and towards paper and fiat money, whose value is based on an agreement to acknowledge its value within a community, Islamic scholars have sought to try to explain the place of such money in an Islamic legal context. This has included suggestions that fiat money takes the role of precious metals, that it replicates the use of fulus in the early days of Islam, or that it is simply a good that is traded. Some have argued that no currency that is not underpinned by gold or silver can legitimately be treated as money from an Islamic perspective. In practice, paper money has become functionally equivalent to gold and silver money through the authority of the state that issued it, and ultimately, by general consent of the community who use it.

How then might Bitcoin and cryptocurrencies more broadly fit within the conception of money from an Islamic legal perspective. In its current stage of development, Bitcoin would not yet appear to fully fulfil the characteristics of money in Islamic law as described by classical Islamic scholars or as reflected in the use of fiat money across the Muslim world. While Bitcoin can be used as a unit of account or measure of value of goods or services, the measure of value that it ascribes to a good or service is frequently presented in parallel with the relevant price in a mainstream currency – the price of the thing is, therefore, simply converted into Bitcoin, rather than being measured solely in Bitcoin. This would lean against a view that Bitcoins are consistently being used as a measure of value. Similarly, in terms of being a store of value, although the value of conventional currencies (as, indeed, the value of gold and silver) fluctuates, a store of value as volatile as Bitcoin would not appear to be very useful. This would mitigate against its widespread use as an alternative form of payment to conventional currencies.

In terms of being a medium of exchange, while Bitcoin’s use as a method of paying for goods and services is increasing, this use is not widespread. As a medium of exchange, Bitcoin only works within a limited number of venues rather than on the basis of the general consent that it can be used as such by the transacting public. As such, Bitcoin cannot be readily exchanged for goods and services. Bitcoin, or any cryptocurrency, could not, therefore be said to yet have widespread social adoption as an alternative to money or currency. This is not to say that Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies could not ultimately be classified as money – if cryptocurrencies mature to become more widely used as an alternative to mainstream currencies, it seems likely that they may be classified as money. It would then be for Islamic scholars to determine if certain cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin are money, whether their use as a form of money is legitimate from an Islamic legal perspective.

For now, Bitcoins and similar cryptocurrencies currently operate closer to non-monetary assets in a digital form in terms of their use in transactions. They serve a money function in part, but would not yet appear to have met the characteristics of money from an Islamic legal perspective. Though Bitcoins and other cryptocurrencies are intangible, they are separable from those who own them, they can be owned, divided, sold, and form the object of a contractual or other legal rights.

They are valued for their scarcity – as such, the value of Bitcoins is not set by centralised authorities, or open to manipulation by those authorities. Instead, it is impacted by market forces and supply and demand – these are a finite asset acquired through human effort that is exchangeable, storable and identifiable. On this basis, they might currently be seen as permissible mal (wealth and property) from an Islamic legal perspective. In the conventional sector, this idea of cryptocurrencies being non-monetary assets and property capable of being owned has been reinforced by the English courts in AA v Persons Unknown, where the English High Court affirmed that Bitcoins constitute ‘property’. Turning first to the traditional definition of property, the court in AA v Persons Unknown noted, referring to Colonial Bank v Whinney, that all property must be one of two kinds – choses in possession or choses in action. Notwithstanding the fact that Bitcoin is neither a chose in possession or a chose in action, the court in AA v Persons Unknown found that this did not stop it from treating cryptocurrency as an asset that is property. Guided by statements from the UK jurisdiction Task Force in its report ‘Crypto Assets and Smart Contracts’, Bryan J noted that ‘I consider that crypto assets such as Bitcoin are property.

They meet the four criteria set out in Lord Wilberforce’s classic definition of property in National Provincial Bank v Ainsworth [1965] AC 1175 as being definable, identifiable by third parties, capable in their nature of assumption by third parties, and having some degree of permanence.’ A similar conclusion that cryptocurrency is property was reached in the Singapore International Commercial Court in B2C2 Ltd v Quoine PTC Ltd.

Looking to the Future

The position of Bitcoins specifically, and cryptocurrencies more generally in Islamic finance is likely to continue to evolve in line with developments in the conventional sector, and any legislative intervention clarifying the legal classification and treatment of this new asset class. In the absence of clear legislative guidance, Bitcoins in the conventional sector would appear to be classified as assets, capable of being traded, and with respect to with proprietary rights exist. From an Islamic legal perspective, there is yet to be any clear consistent guidance on this. However, a review of the relevant definitions in Islamic law would lean towards a suggestion that Bitcoins are not yet money, but are assets in Islamic law.

Ultimately, if the Islamic finance industry is to fully engage with cryptocurrencies, a clear statement from one of the standard-setting bodies within the Islamic finance industry would help the industry to move beyond the current questions of haram and halal and to more effectively adapt as the market itself continues to evolve. This could then open up the cryptocurrency market to the Islamic finance market, allowing Islamic finance to benefit from cryptocurrencies’ ‘inevitable’ growth.

Conclusion

The contemporary Islamic finance industry has proven itself to be adaptable and amenable to innovation over its comparatively short history. Its structures and market participants have gained an identifiable share of the global financial market, reflecting a growth trajectory. It is, however, through continued innovation and openness to new products and services that this growth trajectory can be maintained – the success of the Islamic finance industry to date cannot be used to justify complacency when it comes to innovation.

Unlike the conventional sector, where innovation is limited largely by regulatory hurdles and market appetite, the Islamic finance sector also faces the extra step of needing to ensure compliance with Islamic legal principles and the potential for disagreement regarding the legitimacy of innovative products and services. This does not prevent innovation, but does add to its complexity. For responsible finance sukuk, support of the industry, and broad acknowledgement as to the compatibility of these products with Islamic legal principles, has been an enabler of their growth in the market. With the emergence of social and sustainability sukuk, we are already starting to see the industry respond positively to this development. For Bitcoin and cryptocurrencies, on the other hand, debate continues to rage on. While this has not stopped the emergence of some products seeking to adapt cryptocurrencies to the Islamic finance market, it has, arguably, made it difficult for the Islamic finance industry to meaningfully penetrate the burgeoning cryptocurrency sector.

Innovation should never be rushed, particularly when it comes to ensuring its compliance with religious legal principles. But it is with innovation that the Islamic finance industry will be able to continue accessing growth opportunities in the long term.