Introduction

As a leading international hub for Islamic banking and finance (IBF), Malaysia has always been seen as a jurisdiction which has successfully established its own unique model and set new benchmarks for the regulatory and supervisory framework for IBF. The success of the Malaysian model is even more outstanding considering that, compared to other OIC member countries, it is a diverse nation in terms of race, culture and religion, and its Muslim population control less than 30% of the nation’s wealth as compared to its non-Muslim population.

This chapter summarizes the Malaysian model of regulating and supervising IBF, covering its historical development, strategic framework and foreseeable trends moving forward.

Defining ‘Regulatory and supervisory approaches’

‘Regulatory and supervisory approaches’ refers to the various frameworks purposefully and strategically put in place by the respective Malaysian authorities to deal with specific areas such as the licensing of IBF institutions; requirements for capital adequacy, risk management, Shari’a-compliance and corporate governance amongst IBF institutions, and the establishment of infrastructures such as capital and money markets, dispute resolution forums and talent enrichment institutions, as well as short, medium and long term strategies for the IBF industry generally. This conceptual understanding is important to ensure that one appreciates and recognizes the complex and sophisticated interface between different levels of regulatory and supervisory framework for IBF in Malaysia. These frameworks are developed through cooperation between different bodies and agencies including:

- statutory authorities such as the Ministry of Finance (MoF), Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM – the Central Bank), Securities Commission of Malaysia (SC), Labuan Financial Services Authority (Labuan FSA) and the Inland Revenue Board (IRB);

- exchange authorities such as Bursa Malaysia (Bursa- Mal) and Labuan Financial Exchange (LFX);

- self-regulatory bodies and industry associations such as Association of Banks in Malaysia (ABM), Association of Islamic Banking Institutions Malaysia (AIBIM), Malaysian Investment Banking Association (MIBA), and Malaysian Takaful Association (MTA).

As may be observed in the later sections, the regulatory and supervisory approaches for IBF in Malaysia have been developed with clear strategic objectives of, among others:

- ensuring public confidence in the soundness and competitiveness of the Islamic financial system;

- meeting local needs without compromising on international standards and best practices;

- addressing the market’s various short-term and long-term needs, depending on the stage of its development;

- providing a conducive environment for business development and talent enrichment; and

- expanding the width and depth of the industry through internationalisation of local players and liberalisation policies that attract participation of foreign players.

historical development

Rome was not built in a day. Similarly Malaysia has endured its own long journey in developing its IBF industry. Although Malaysia’s first fully Shari’a-compliant financial institution i.e. Tabung Haji (the Pilgrimage Fund) was established as early as 1963, a real drive towards establishing infrastructures for a proper IBF industry to flourish only began about twenty years later, marked by the enactment of an Islamic Banking Act (IBA) in 1983. From then onwards, the framework for the IBF industry in Malaysia underwent three main phases of development:

- First phase: 1983-1992

Early initiatives were focused on building the necessary legal and infrastructural foundations that would enable IBF to be gradually introduced and developed, without causing any disruption to the existing conventional banking system. As opposed to Iran, Pakistan and Sudan which attempted to Islamise the whole financial system through radical reforms at around the same period, Malaysia deliberately opted for a dual-banking system approach whereby IBF could co-exist with its conventional cousins and offer an alternative range of products and services to the people. When the IBA was enacted, it was the world’s first piece of Islamic banking legislation as well as Malaysia’s. Takaful Act 1984 immediately followed a year later, which again marked the first legislation in the world that was tailor-made to govern the takaful (Islamic insurance) business.

During this period, Bank Islam Malaysia Berhad (BIMB) was the only full-fledged Islamic bank; a second full-fledged Islamic bank, namely Bank Muamalat Malaysia Berhad (BMMB) was only licensed in 1999. Although it seems as if the government deliberately granted a monopoly to BIMB to dominate the IBF market throughout these years, it is possible that the authorities wanted to ensure that they had adequately learnt and understood the business and market dynamics of an IBF institution properly before increasing the number of institutions in the market.

- Second phase: 1993-2000

Within 10 years of the establishment of BIMB, more than 20 IBF products had become available in the Malaysian market. By then, the authorities considered the IBF market ready for the second phase: to increase the number of players, increasing competition as an incentive to improve efficiency and enhancing the overall market vibrancy. This phase witnessed the following:

– in 1993, permission was granted to conventional banks to offer IBF products and services through a ‘window’ concept known initially as the “usury-free banking scheme”, which gradually came to be known as the “Islamic banking scheme”. Although the Islamic window branches were owned by conventional banks, the operation and sources of funds of the window operations were completely separated from those of their holding conventional banks.

- the development of an Islamic capital market (ICM) marked by the issuance of the first Islamic security (now more popularly known as sukuk) by Shell MDS in 1990

- the establishment of a National Shari’a Advisory Council (NSAC) at both the SC and BNM (in 1996 and 1997 respectively).

The opening of Islamic bank window branches by conventional banks was legally made possible as the result of legislative amendments, specifically section 124 of the Banking and Financial Institution Act 1989 (BAFIA). This provision is consistent with the Government Investment Act 1983 (GIA) which was introduced earlier, and section 129 of the Development Financial Institution Act 2002 (DAFIA) which was later introduced in 2002.

By 1994, Malaysia had advanced its IBF market to the next step by setting up the Islamic Interbank Money Market to enable transactions in the wholesale money market on an Islamic basis.

- Third phase: 2001-2010

The third phase of the IBF industry in Malaysia saw concerted efforts towards making it a truly global IBF centre. Two strategic documents, namely the BNM’s Financial Sector Master Plan (FSMP) and the SC’s Capital Market Master Plan (CMMP), are both 10-year roadmaps that alleviated IBF and ICM into the mainstream of Malaysia’s economic agenda, with specific strategic reforms and goals proposed and executed. This phase was also marked by the following events:

- the liberalisation of the market through licensing of foreign Islamic banks;

- the launch of MIFC initiative, which is a community network of financial and market regulatory bodies, Government ministries and agencies, financial institutions, human capital development institutions and professional services companies that are participating in the field of Islamic finance with the aim of positioning Malaysia as the preferred international Islamic finance hub;

- the selection of Malaysia to be the host country for the IFSB and the International Islamic Liquidity Management Corporation (IILM); which are two supranational organisation critical to the development of the global IBF industry;

- the setting up of the Malaysian Deposit Insurance Corporation (MDIC) that also covers Islamic deposits; and

- the establishment of various talent development and research institutions dedicated to IBF, including the Institute of Islamic Banking and Finance Malaysia (IBFIM), International Centre for Education in Islamic Finance.

(INCEIF), International Shari’a Research Academy for Islamic Finance (ISRA), Securities Industry Development Corporation (SIDC) and SC’s ICM-Capital Market Development Fund initiatives. Despite intense competition from other financial centres aspiring to be the preferred hub for Islamic finance, Malaysia so far has managed to remain at the forefront and has won numerous awards and accolades as the best international Islamic financial centre.

Strategic Framework

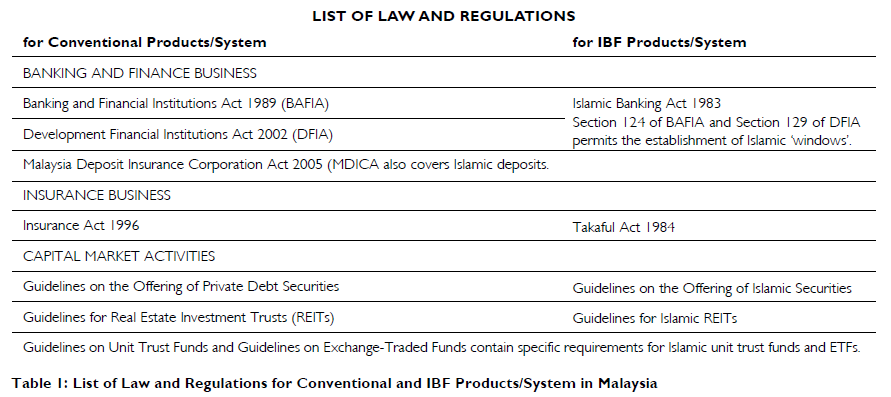

As aforementioned, Malaysia adopts a ‘dual’ financial system which allows harmonious co-existence of IBF alongside the conventional financial system. In this respect, it is obvious that the authorities attempted to provide for IBF an enabling legal framework whereby anything that the conventional system can offer would always have an Islamic parallel or alternative. This is evident by the introduction of separate legislation and regulations to cover matters of similar nature, as reflected in Table 1.

The importance and clarity of the law and regulations as listed above cannot be overemphasized, because they form the backbone of every aspect of IBF operations in Malaysia. In other words, the development of activities of every IBF player are guided and dictated by the strong backing of law and regulations, leaving nothing to mere assumption or chance.

- Strengths and advantages of the Malaysian model

Beside its ability to spur the growth of the IBF sector amidst a very diverse populace and within an economic environment strongly dominated by non-Muslims, it is worth mentioning that the Malaysian model has proven its resilience in the wake of two financial crises- namely the Asian financial crisis in 1997 and the recent global financial crisis. Without doubt, the Malaysian model has grown from strength to strength and can provide useful benchmarks to other jurisdictions which aspire to develop their own IBF industry.

The strength and advantages of the Malaysian model are numerous and deserve an analysis on their own. However, in summary, amongst the obvious advantages of the Malaysian model are the following:

- Sound and clear Shari’a-compliance and governance framework

The existence of a structured and powerful National Supervisory Advisory Council (NSAC) was originally in- tended to ensure clarity in terms of fiqh muamalat practices, but today it also has the power of final arbiter on Shari’a issues in any IBF dispute. By having legal authority, there will be coherence and assurance of validity of pronouncements by Shari’a scholars. In most other jurisdictions, the status of Shari’a pronouncements for IBF contracts remains vague and ambiguous when it comes to enforcement under the law.

- Tax accommodations

In Malaysia, concerns about IBF contracts potentially attracting additional taxes that would make their products less competitive as compared to conventional financial contracts have since died down. The tax authorities, namely the MoF and the IRD have always cooperated with BNM and SC to ensure that, in a worse-case scenario, there will be tax neutrality between what has to be paid under an IBF transaction and what would be paid under a conventional financial transaction. In certain best-case scenarios, special tax incentives including remittance and rebate are given to encourage the use of IBF structures by market players.

- Certainty and predictability of dispute resolution outcomes

By virtue of the common law system inherited from the British colonialists, the Malaysian courts apply the doctrine of judicial precedent and publicly report landmark decisions, thereby facilitating the development of certainty and predictability of dispute resolution outcomes for IBF cases.

The Reciprocal Enforcement of Foreign Judgments Act (1958) generally recognizes the decisions made in courts of other common law jurisdictions such as the UK, Hong Kong, Singapore, thereby providing clarity on the enforceability of judgments obtained from the courts in these jurisdictions, even when it comes to IBF disputes. It also has a clear insolvency regime that permits speedy debt recovery and liquidation of assets, including for IBF institutions.

To add further depth to these capabilities, the Kuala Lumpur Regional Centre for Arbitration (KLRCA) provides a convenient alternative dispute resolution platform by having a specific rule to govern disputes involving IBF matters. The Rules for Arbitration (Islamic Banking and Financial Services) 2007 was specially drafted and introduced to provide a customized platform and mechanism for the resolution of disputes in the Is- lamic financial services sector.

- Talent enrichment and thought leadership infrastructures

Central to its ambition to be a preferred international Islamic financial centre, Malaysia appreciates the importance of ensuring that its IBF sector is supported by a sizeable pool of competent human capital. It has established numerous unique institutions dedicated to talent enrichment and thought leadership, including:

- 2001 – Islamic Banking and Finance institute Malaysia (IBFIM)

This institution is truly unique. It is owned by IBF institutions and its primary role is to provide training and consultancy. It focuses on programmes related to IBF and ICM. IBFIM’s mandate can be best described by referring to the FSMP where it mentions about IBFIM,

“to increase the pool of bankers and takaful operators who are knowledgeable and competent, efforts will be directed to promote human capital development to support the envisaged growth of the industry via establishing an industry-owned institution on Islamic banking and finance dedicated to train and supply a sufficient pool of Islamic bankers and takaful operators as required by the industry”.

Similarly the CMMP mentions that IBFIM is ‘to develop local expertise to ensure the availability of a pool of skilled professionals who are well-versed in Syariah matters and are able to provide a range of relevant high-quality value-added advisory and intermediation services’.

- 2003 – International Centre for Leadership in Finance (ICLIF)

Apart from providing training and consultancy, Malaysia realized that there is a need to start grooming and supplying leaders for its IBF market, especially if it wishes to see Malaysia become a world-class IBF hub. Hence, a well-structured development programme focusing on leadership capacity building for financial institutions and business corporations has been introduced by BNM, known as ICLIF. ICLIF is mandated to provide training and development programmes for young and intermediate leaders by offering short courses ranging from 2 to 4 weeks. The programmes offered by ICLIF are designed for specific needs, for instance, to groom middle-class managers who are expected to be promoted in two years time. ICLIF is supported with resources from various prestigious institution around the world including Harvard Business School, Stanford Graduate School of Business, Drucker School of Management, University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) and University of California at Berkeley (UC Berkeley).

- 2006 – International Centre for Education in Islamic Finance (INCEIF)

INCEIF is a global university offering expertise certification in various IBF-related disciplines at postgraduate level. Students enrolled to this programme come from various countries and INCEIF graduates are trained to become professionals of IBF in its programmes which are offered in three levels namely Chartered qualification, Masters and Ph.D. INCEIF received a generous grant of RM500 million from the Malaysian government to realise its vision to become the knowledge leader in Islamic finance industry.

- 2008 – International Shari’a Research Academy for Islamic Finance (ISRA)

Unlike many other institutions that focus on develop- ing human capital, ISRA was established to enhance literature and research on Shari’a and fiqh ul muamalat. It provides an international platform to encourage discourse among Shari’a scholars, academicians, regulators and practitioners. To date, ISRA has organized many programmes and published various literature on the IBF industry.

- Depth and Width of its Capital Market

Following the Asian financial crisis at the end of the 1990s, the Malaysian authorities recognized that amongst the weak links within its financial system was the heavy dependence of the economy on borrowing from financial institutions to spur further growth. Since then, it has consciously developed its capital market, including the ICM, and has emerged as the largest bond market in Asia after Japan. Bonds and sukuk issued in the local currency, Ringgit (RM), has developed their own strengths and profile to enable issuers whether local or foreign, to generate capital in a cost-efficient manner to the extent that the RM sukuk market is hardly affected, notwithstanding slowdowns in the sukuk market elsewhere as seen during the recent global financial crisis.

- Deposit insurance protection

Malaysia is the only country in the world which has a deposit insurance corporation that covers both conventional and Islamic deposits. The innovation made by the MDIC in this respect certainly has helped in strengthening public confidence in IBF institutions.

a word of caution

Notwithstanding its enviable merits and record of success, it should be noted that the Malaysian model is championed by a supportive and prescient government which has advocated reforms conducive to the development of Islamic finance. A heavy and dominant leadership of government authorities would be an absolute luxury for the IBF sector in most other jurisdictions. In this respect, it is not fair to compare the Malaysian model with the regulatory and supervisory approaches in other countries. It remains to be seen whether the Malaysian IBF industry can remain robust and vibrant if the government decides to take a back- seat and leave the next stage of development entirely to the market.

As it has deliberately decided to adopt a ‘dual’ financial system, the IBF sector in Malaysia is also under constant pressure to remain competitive against its conventional counterpart, and hence, it remains to be seen whether the IBF players can withstand such pressure without the intervention of a helping hand from the authorities in the form of regulatory ‘green lane’ or tax incentives.

Foreseeable trends, moving forward

law Harmonisation Committee

BNM has established a Harmonisation of Law Committee, chaired by the highly respected former Chief Justice of the Federal Court of Malaysia, Tun Abdul Hamid Mohamad. The Committee is established with the following objectives:

- To create a conducive legal system that facilitates and supports the development of the Islamic finance industry;

- To achieve certainty and enforceability in the Malaysian laws in regard to Islamic finance contracts;

- To position Malaysia as the reference law for international Islamic finance transactions and;

- For Malaysian laws to be the law of choice and the forum for settlement of disputes for cross-border Islamic financial transactions.

It is observed that all this while English law has been the preferred law of reference for international Islamic finance transactions, therefore the objective of the Committee is arguably very ambitious. Considering that English law has a long tradition of being the reference law for international contracts and English courts command enormous respect in the international arena for its impartiality and independence, there are many reasons for people to be sceptical. However, if we consider that Malaysia is simply offering a value proposition whereby parties to an international Islamic finance contracts are comfortable that:

- The jurisdiction is neutral and impartial to all parties in the contract;

- The Malaysian law offers absolute certainty and predictability with regard to Shari’a issues, as the NSAC is the final arbiter on such matter – which no other jurisdictions can offer;

- The Malaysian courts and arbitration centre are competent in dealing with disputes arising from IBF contracts; then there is no reason to reject the possibility of making Malaysian law as the reference law for IBF contracts.

Initiatives to govern the Shari’a scholar profession

ISRA has announced its plan to come up with the first global certification for Shari’a scholars, seeking to bolster the industry’s reputation and make it easier for banks to find qualified advisers. As it is, the Shari’a-compliance and governance framework in Malaysia is already highly regulated compared to anywhere else in the world, with the BNM and SC each issuing specific guidelines on the appointment of members of Shari’a Committee and imposing various fit and proper requirements comparable to any other regulated professions that serve the financial services industry such as directors and auditors. Through its annual Muzakarah Cendekiawan Shari’a Nusantara (Regional Shari’a Scholars Symposium), ISRA is progressively building consensus amongst scholars in the South East Asia region. If they manage to build on this and expand the scope and strength of the dialogue platform to other parts of the world, especially in the Middle East and Africa, there is a higher possibility for this initiative to transform into a more globally accepted professional association of Shari’a scholars that can provide a recognised certification and governance regime for this important group of gatekeepers in the IBF industry.

While it is well acknowledged that the Shari’a profession is largely fragmented into various schools of thoughts and in this respect remains an obstacle in bringing standardization of Shari’a best practices for the global IBF industry, ISRA has the appropriate government backing and a strong team that have so far done well in establishing its stature in the international arena. Hence, there are reasons to be optimistic that it can contribute positively towards establishing a better set-up for the Shari’a scholar profession in the future.

Conclusion

Malaysia has shown that with proper planning and effective strategies, it has managed to overcome many challenges in developing its IBF industry, including withstanding two devastating periods of financial crisis. It has undertaken thoughtful and carefully calculated proactive as well as reactive steps in bringing IBF as a value proposition at the global stage. Its ability to establish cutting-edge regulatory and supervisory framework that caters to local needs but meets emerging international demands is certainly commendable. If there are reflections that can be summarized from its long arduous journey to establish itself as a leading Islamic financial centre, it is that Malaysia has been continuously learning and adapting its regulatory and supervisory approaches to the challenges faced, and innovating expeditiously throughout the different phases of its IBF development.