Introduction

The sub-prime financial crisis was not simply the result of excessive leverage and inadequate capital but also concoction, of a gradual deterioration of business leadership, lapses of governance in the regulatory framework (particularly in derivatives markets) and an ineffective risk-management framework, that had been brewing for some time. There is consensus among researchers that the regulatory and supervisory framework was not adequate to forecast and prevent the crisis. However, the crisis itself has highlighted several regulatory and governance-related issues: the market-discipline mechanism proved to be too weak; the decision-making of corporate leaders was overly driven by short-term goals; trust in corporate leadership declined; corporate boards were slack in their oversight and risk control; business ethics and values were compromised; risk management and supervision failed due to a lack of foresight; the quality of bank supervision was compromised; and finally, the corporate incentive and remuneration system was skewed in favour of financial results over responsibility.

The consequences of the crisis on the way financial intermediation and markets operate will be felt for many years, impacting not only conventional financial institutions but also their Islamic counterparts.

Core issues shaping the future of regulatory and supervisory framework for the financial industry

- Failure of market discipline

“What has occurred is a shock to a set of intellectual assumptions about the way that markets work, about their self-equilibrating character.”

Lord Turner, IOSCO, June 11, 2009

The financial crisis has disproved the widely held notion that the invisible hand of the market would instil market discipline and resolve conflicts amongst market players without any further need to regulate the market. It was soon realized that not only was the financial-market information incomplete, but that the market could be manipulated by market players for their own personal interests. This observation is particularly applicable to the derivatives and structured markets, where the level of complexity is higher than markets for other financial products. This failure of market discipline led by financial innovation undermined the effectiveness of a regulatory model that rested, at least in large part, on transparency, disclosure, and market discipline to curb excessive risk-taking.

- Failure of corporate governance and risk management

“Corporate governance is one of the most important failures behind the present financial crisis.”

De Larosière Group (2009)

“This Report concludes that the financial crisis can be, to an important extent, attributed to failures and weaknesses in corporate governance arrangements.”

OECD report (2009)

It was only after the Asian crisis of 1997-98, that issues of corporate governance caught the attention of policy-makers and were highlighted to strengthen the overall governance and risk management framework. However, the current financial crisis has shown that al- though governance and risk management frameworks were in place, they failed to prevent a crisis before it erupted. Managers focused on short-term profit generation and boards neglected their task to probe tough questions.

The role of board oversight in the governance structure of financial institutions is critical, but this oversight function was undermined by the offer of high levels of remunerations to board members in exchange for their loyalty, even before the current financial crisis. The failure of the boards to determine and monitor the strategy and risk appetite of the company and to respond in a timely manner was evident in many cases. Even when there was a proper risk-management framework in place, boards failed to take timely action. Although the role of the boards of financial institutions has increased dramatically over the last decade, they have been criticized for being too complacent and unable to prevent collapses.ii A recent G-20 report concluded that “the current financial crisis is a classic example of board failure on strategy and oversight, misaligned or perverse incentives, empire building, conflicts of interest, weaknesses in internal controls, incompetence and fraud.”

Weaknesses in safeguarding against excessive risk-taking behaviour in a number of financial-services companies were exposed during the current financial crisis. Even when the risk models gave signals of trouble, lax corporate governance meant that often no action was taken by senior management because such information never reached them or they judged it to be of little importance. While the failure of certain risk models can be put down to technical assumptions, the way in which the information was used in organizations was also a major contributor to this.

- Breach of trust

The current financial crisis has significantly damaged aspects of social capital. The Edelman Trust Barometer, which tracks the level of trust in different countries, observed that people began to lose trust in business leaders and became critical of their irresponsible actions, especially in the US.v In the case of the United States, home to some of the largest corporate collapses, trust in business leaders dropped 20% points as a result of the crisis. At just 38 %, this was even lower than the levels witnessed during the Enron and dot.com crises and came close to the levels in Western Europe, which has historically displayed the lowest trust levels in businesses amongst all nations surveyed by the tracker. Similarly, survey clearly showed a sharp decline in the trustworthiness and credibility of CEOs in all major industrial economies.

- Deteriorating business ethics and values

The current financial crisis has also highlighted a decline in moral and ethical values in senior management, who cared less about moral edifice and focused more on circumventing regulatory constraints and finding loophole in the law. Greed and personal empire-building became the norm on Wall Street with little emphasis being placed on producing moral and ethical business leaders.

Key drivers of change

There is no doubt that the lessons learnt from the crisis will shape the changes in the regulatory and supervisory framework and practices. The debate on which direction a policy-maker needs to take has already been heating up on several international forums, including the Financial Stability Forum (FSF), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), national authorities, and standard-setting bodies who are collaborating to address deficiencies and invoke enhancements. Working groups at FSF and the G-20 are reviewing a wide spectrum of related issues including complex and difficult legal and institutional hurdles to improve cross-border cooperation in regulation and the resolution of troubled institutions.

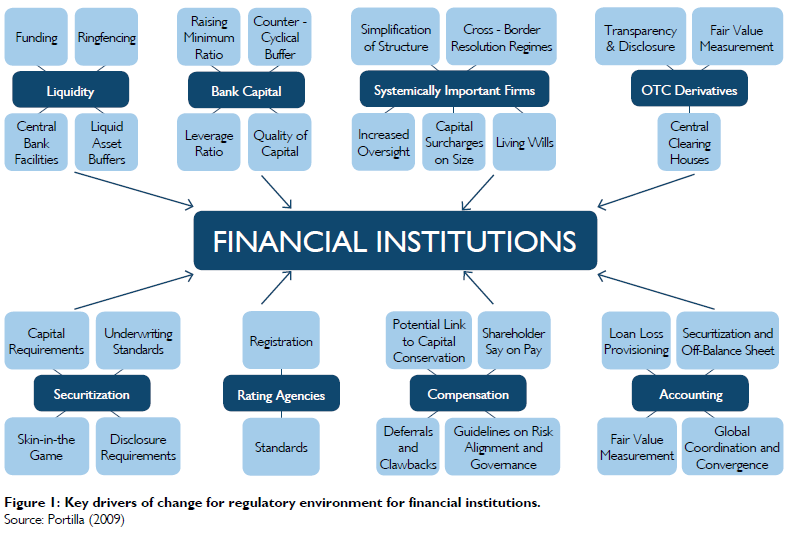

Figure 1 is a very good depiction of how financial institutions were surrounded by different pressure points which came to surface during the crisis. This gives an idea of the nature of the issues under consideration for shaping new financial landscape. The environment within which today’s financial institutions are operating is changing and the key drivers for change include defining capital and its adequacy, liquidity, securitization, rating agencies, compensation, OTC derivatives, and systemically important entities. In this section, select key drivers will be discussed, along with how each driver will impact the Islamic financial services industry.

- Capital Requirements

The first realization is that in the increasing complexity of the present financial system and growing innovative practices of financial institutions, activities cannot be sustained with the current capital requirements without clear segregation of commercial and investment banking activities. Keeping this in mind, Basel III recommends that financial institutions substantially raise the quality and quantity of capital with a much greater focus on common equity to absorb losses. Enhanced capital buffers can help protect the banking sector against credit bubbles that can be drawn down during times of stress. Key features of Basel III’s new capital requirements include (i) increase of the minimum levels of capital under Basel (6%-8% Tier 1); (ii) change of rules in regard to composition/definition of capital (66%-75% from Tier 1 composed of retained earnings and common stock); (iii) requirement of countercyclical shock-absorbers/buffers (that vary with the economic cycle); (iv) requirement of a leverage ratio, limiting asset size (both on and off-balance sheet.); and (v) additional charges of capital related to firms considered systematically relevant. Proposed changes in the capital requirements are a step in the right direction. The IFSB has already announced a review of existing capital adequacy requirements in light of the proposed Basel III requirements. Determination of capital requirements for IFIs is not straightforward.

There are two main issues. First, technically, IFIs is supposed to be on “pass-through” mode, where all profits and losses on the asset side are passed to the liability side (to investors/depositors) and therefore, the need for capital is minimal. In this mode of intermediation— just like mutual funds—the purpose of capital is to cover negligence and operational risk. However, the reality is that capital requirements have been set on similar lines for IFIs as they have for conventional banks to maintain the confidence of investors. Along the same vein, it is expected that the capital requirements for IFIs will also be modified to comply with Basel III. Increased capital requirement can also impact the efficiency and return on equity for IFIs.

The second issue with capital requirement concerns the exposure of IFIs to real assets that are subject to price volatility as well as to liquidity risk. It is observed that several Islamic banks, especially in the Middle East have considerable exposure to the real estate sector. Depending on how the assets are valued—book value or market value, the financial health of Islamic banks can deteriorate as a result of price volatility. In addition, requirements to adjust capital to economic cycles and Islamic banks’ activities to the real sector will come into play in determining new capital requirements. Policymakers and authorities can develop sophisticated capital requirements to combat pro-cyclical pressures only after they understand the nature of risk/return reward of assets of IFIs which are definitely different from their conventional counterparts. Since Basel III will change capital charge for securitization risks, IFIs dealing with sukuk market could also expect changes. Finally, as discussed below, additional requirements for liquidity in Basel III will put additional burden on Islamic banks to maintain adequate capital and the levels of minimum capital are expected to increase.

- Liquidity

The current financial crisis is termed a ‘perfect liquidity surprise.’ Liquidity problems associated with the financial crisis have forced the regulators to get tough on this issue. Basel III incorporates the introduction of minimum liquidity standards and monitoring of liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) of financial institutions. The LCR is a ratio meant to ensure that the firm has enough liquid assets to cover a short-term crisis based on a predetermined set of cash inflows and outflows established by the BCBS. Such liquidity issues have serious implications for IFIs for several reasons. First, IFIs do not have access to short-term liquidity through markets. One of the biggest impediments for IFIs is the development of liquid markets where securities can be traded efficiently at minimal transaction cost. Second, due to heavy concentration of trade or commodity finance, assets of Islamic banks are illiquid, i.e. Murabaha-based assets cannot be traded in the secondary market. Third, whereas conventional banks have access to liquidity provided by a lender of last resort, Islamic banks can not benefit from such facility as the lending is interest-based. This means that although, an Islamic bank may be in good financial health but still could face additional capital requirements due to low liquidity which could hamper its growth or efficiency.

- Quality of information

For markets, policymakers and financial authorities, multi-laterals (IMF and World Bank) appropriate coverage and quality of information is increasingly becoming critical for their capacity to assess risks and vulnerabilities. Regulators are looking for better information on the range of financial institutions’ activities such as ‘off balance sheet’ risks (involving better-consolidated supervision), and the risks of financial inter-linkages. New regulatory and supervisory environment will be “information-focused” and financial institutions will be required to enhance the information collection and disclosure as required by the regulators.

What does this mean for financial institutions? This mean that the financial institutions will have to improve, enhance, and upgrade overall flow and the quality of information in their institutions. They will need to be very focused on satisfying the reporting and disclosure requirements for the regulators and supervisors. The financial institutions should expect to address this issue across all business lines and functional areas from front to back office. For some institutions, it would require an upgrade of risk reporting systems or development of new risk measures.

The General level of transparency and disclosure of information is low in the Islamic financial services industry. The impact of quality of information on IFIs could be from two directions. At the institutional level, they would be required to enhance the flow and quality within the institution which could demand automation of manual monitoring processes, upgrading information systems and improving the transparency of data and information for reporting purposes. This could be a challenge considering that majority of Islamic financial institutions are of small size and do not have surplus funds to invest in the information infrastructure.

The quality of information is relevant to investors and also the regulators, but in several countries where Islamic banks operate, the general quality of information is considered low. Table 1 shows a comparison of the information disclosure index of Middle East and North Africa (MENA) countries with G7 countries, and Table 2 shows the depth of credit information in the region. This index measures the rules and practices affecting the coverage, scope and accessibility of credit information available through either a public credit registry or a private credit bureau. The index shows relatively low levels as compared to the developed economies of G7. National authorities and regulators need to take concrete steps to enhance information at a systemic level so that all participants in the system can benefit from it. Enhancing the flow and quality of information can be considered as a key driver where the Islamic financial industry needs to pay attention.

- Risk management practices

As previously mentioned, a failure of risk management was observed during the financial crisis and as a result, risk management practices have come under close scrutiny and a review of the risk framework is expected. It is expected that policymakers and regulators will be taking a very close look at how banks arrive at their measures of exposure, how they risk-weight their as- sets, and how they engage in risk mitigation activities. Requirements from the regulators on risk measures and enhanced quality of information will pressurise financial institutions to be vigilant to requirements for new products and to comply with the regulatory requirements. The risk framework in IFIs is gradually evolving but is still at an early stage. The emphasis is on credit risk management and the awareness of market and operational risk is not adequate. Due to size, some financial houses cannot afford an extensive enterprise-wide risk-management system; which further exposes them to operational risk due to manual processes. In terms of risk technology, there are a handful of technology vendors who are taking their conventional product and offering them to Islamic banks with some modifications. It is critical that a proper risk framework for Islamic products and financial institutions is developed so that meaningful risk measures such as value-at-risk are maintained and proper back-testing and stress-testing of exposures are undertaken to satisfy upcoming requirements.

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |

| Average MENA | 5.86 | 5.86 | 5.94 | 6.13 | 6.44 | 6.56 |

| Average GCC | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.83 | 6.83 | 6.83 |

| Average Non-GCC | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 6.2 | 6.4 |

| Average G7 | 7.71 | 7.71 | 7.71 | 7.71 | 7.71 | 7.71 |

Source: DoingBusiness, World Bank.

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |

| Average MENA | 1.93 | 2.21 | 2.69 | 3.13 | 3.5 | 3.69 |

| Average GCC | 3 | 3 | 3.33 | 3.83 | 3.83 | 3.83 |

| Average Non-GCC | 1.5 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 3.3 | 3.6 |

| Average G7 | 5.71 | 5.57 | 5.57 | 5.57 | 5.57 | 5.57 |

Source: DoingBusiness, World Bank.

- Supervisory framework

In the standard setting area, the focus of policy work is on the market risk rules, systemically important banks, the reliance on external ratings and large exposures. Ba- sel III is the core regulatory response to the financial crisis but with the regulatory changes. The next critical task is to promote more collaborative supervision at the global level. It is expected that authorities will be paying more attention to improve supervisory practices and cross-border bank resolution practices in addition to further development of supervisory standards. The working group on Financial Stability Board (FSB) has identified areas of the Core Principles for Effective Banking Supervision that could be expanded or clarified to address topics related to the supervision of systemically important financial institutions. One key challenge for the bank supervision would be to assess risks associated with innovations and how such exposure is monitored. The main challenge for both supervisors and the Islamic financial industry would be to develop and enhance supervisory framework. If one takes the example of the MENA region where there is large concentration of IFIs; supervisory standards, legal institutions governing the resolution of large cross-border financial firms and insolvency issues are under-developed for both conventional and IFIs. Unless these impediments are removed, the financial system will be prone to instability. The current practice is to treat Islamic banks similar to conventional banks when it comes to supervision but this practice is not optimal. Islamic institutions have different contractual agreements and without understanding the underlying contracts, supervision can overlook areas of potential problems. Although, standards for exposure, governance, and supervision have been issued by IFSB, these standards are yet to be adopted formally by regulators and national authorities. National supervisory authorities may be very familiar with supervision framework and methodology of conventional financial institutions, but they need to pay attention to revising supervisory standards and manuals for Islamic institutions in addition to getting serious about implementing IFSB standards. Another dimension of complexity in supervision is introduced by the existence of “Islamic windows” by conventional banks and the need for maintaining proper firewall to segregate Islamic assets from conventional assets.

As Basel III incorporates macro-prudential measures to help address systemic risk and inter-connectedness of financial systems; regulators and supervisors need to enhance the supervision of Islamic institutions by forcing these institutions to: improve their internal risk systems; compliance with reporting requirements; transparency of disclosures and quality of information. Without focusing on these issues, the authorities would not get a meaningful understanding of the risk such institutions pose to the systemic risk.

Going forward

It is essential that a long-term and broader approach is taken by the industry. It would be a mistake to limit the efforts to short-term goals such as the implementation of Basel III. However, the opportunity should be taken to address structural issues facing the industry. To make high growth sustainable, attention needs to be paid to developing infrastructure and institutions which promote Islamic finance. For example, Islamic finance is considered a risk-sharing system but current practices of Islamic finance significantly diverge from this core feature. Therefore, steps should be taken in this direction to promote the essence of the Islamic financial system which is risk-sharing and promotion of equity-based financing. To foster the development of Islamic finance, there is a need to emphasize its risk-sharing foundation; reduce transaction costs of stock market participation; create a market-based incentive structure to minimize speculative behaviour; and develop long-term financing instruments as well as low-cost efficient secondary markets for trading equity shares. These secondary markets would better enable the distribution of risk and achieve a reduction in risk with expected payoffs in line with the overall stock market portfolio.

Further, there should be a collective and collaborative effort by all the stakeholders in the Islamic financial services industry to meet the upcoming challenges. Key stakeholders such as IDB, IFSB, AAOIFI, and key central banks such as that of Malaysia and Bahrain need to pool resource together and work with international standard-setting bodies and multilateral institutions such as the IMF for coordinated response to upcoming regulator and supervisory changes. the Task Force on Financial Stability and Islamic Finance recommended that an Islamic Financial Stability Forum (IFSF) be established as a broad-based and constructive strategic platform to promote financial stability within the Islamic financial system. Such forum should collaborate closely with the Financial Stability Board (FSB) to exchange ideas on strengthening financial stability of IFIs. Without a common platform, it would be difficult for individual national authorities who might be preoccupied with adjusting to changing environment for conventional institutions to pay due attention to issues of the Islamic financial services industry.

As mentioned earlier, it is essential to develop a set of comprehensive, cross-sectorial prudential standards and supervisory framework covering not only Islamic banks, but also takaful companies and capital markets. The IFSB who has issued standards, needs to be more forceful in convincing national authorities to implement such standards. The IFSB also needs to seek help from the IMF to fill the gaps in standards and adequate training of national authorities. One of the challenges in the implementation of the macro-prudential framework is the development of key financial indicators which serve as benchmark for the assessment of financial soundness and exposures to vulnerabilities of the financial system. Such indicators also facilitate a relative assessment of their interaction with broader macroeconomic developments. This task requires: a design of indicators to suit IFIs; comprehensive statistics of financial institutions’ activities; high-quality of information available and design of templates to undertake financial sector assessments.

The development of efficient legal and economic institutions and a sound governance framework is important for the emergence and growth of a sound financial system. Institutions lay the foundation of the system and the governance framework ensures that the rules are enforced so that the desired results are achieved. The Islamic financial system is based and centred on risk sharing and affording equity finance a pre-eminent position in the financial system. Given the moral hazard and agency problems associated with equity-based financial contracts, institutions and governance become even more important in developing a risk-sharing financial system. Institutions governing economic transactions such as property rights; trustworthiness, truthfulness, fatefulness to the terms and conditions of contracts, transparency, and non-interference with the workings of the markets and the price mechanism so long as the market participants are compliant to the rule-provide a reasonably strong economy where information flows unhindered, and participants engage in transactions confidently with minimal concern for uncertainty regarding the actions and reactions of other participants. The result is that in such an economy with reduced uncertainty, economic agents will be encouraged to engage in risk-sharing contracts. Finally, while conventional finance also expects business leaders to exhibit ethical behaviour, it does not have a sound enforcement mechanism other than market discipline, which has come under a scathing attack during the current financial crisis. On the other hand, the Islamic financial system derives its values from the teachings of Is- lam and can expect ethical governance from the leaders, managers, and other stakeholders, who follow the rules prescribed by the Shari’a. Promoting ethical governance that fosters trust and formal governance mechanisms will become more effective in protecting the interests of stakeholders. Leaders of the Islamic financial industry should realize the importance of this enormous responsibility of not only behaving in an ethical manner but also to promote the best business ethics across their institutions.