Wealth management has been defined as “a practice that in its broadest sense describes the combining of personal investment management, financial advisory, and planning disciplines directly for the benefit of high-net-worth clients.” Islamic wealth management is the provision of wealth management services in a manner that is consistent with Islamic principles as interpreted by Shari’a scholars. The above definition is applicable globally. However, tax law is always jurisdiction specific. Accordingly, this chapter outlines some generic taxation issues that need to be taken into account in the provision of Islamic wealth management services, and provides specific illustrations of how they are dealt with in one jurisdiction with a relatively advanced system for taxing Islamic finance, the United Kingdom, to provide some pointers as to how other jurisdictions should treat those issues. However, it does not attempt to survey the tax treatment in other jurisdictions.

Taxation of Estates and Inheritances

Assisting the client with their estate planning is normally an integral part of wealth management. A will is almost always desirable, as otherwise the jurisdiction will impose its own rules of intestate succession if the client dies.

For Muslim clients, there will often be a conflict between the way they wish to draw up their will and the way the jurisdiction taxes estates and inheritances. The UK’s tax law illustrates this conflict.

Islamic Rules of Succession

The Quran 4:11-12 sets out specific rules of inheritance:

CONCERNING [the inheritance of] your children, God enjoins [this] upon you: The male shall have the equal of two females’ share; but if there are more than two females, they shall have two-thirds of what [their parents] leave behind; and if there is only one daughter, she shall have one-half thereof.

And as for the parents [of the deceased], each of them shall have one-sixth of what he leaves behind, in the event of him having [left] a child; but if he has left no child and his parents are his [only] heirs, then his mother shall have one-third; and if he has brothers and sisters, then his mother shall have one-sixth after [the deduction of] any bequest he may have made, or any debt [he may have incurred]. As for your parents and your children – you know not which of them is more deserving of benefit from you: [therefore this] ordinance from God. Verily, God is all-knowing, wise.

And you shall inherit one-half of what your wives leave behind, provided they have left no child; but if they have left a child, then you shall have one-quarter of what they leave behind, after [the deduction of] any bequest they may have made, or any debt [they may have incurred].

And your widows shall have one-quarter of what you leave behind, provided you have left no child; but if you have left a child, then they shall have one-eighth of what you leave behind, after [the deduction of] any bequest you may have made, or any debt [you may have incurred].

And if a man or a woman has no heir in the direct line, but has a brother or a sister, then each of these two shall inherit one-sixth; but if there are more than two, then they shall share in one-third [of the inheritance], after [the deduction of] any bequest that may have been made, or any debt [that may have been incurred], neither of which having been intended to harm [the heirs]. [This is] an injunction from God: and God is all-knowing, forbearing.

Without attempting to consider all possible circumstances, if a woman has both a husband and children, under the Islamic rules of succession ¼ of the estate will pass to the widower, while ¾ will pass to other inheritors. If a man has both a wife and children, his wife will inherit 1/8 while 7/8 will pass to other inheritors.

UK Inheritance Tax law

The taxation of estates in the UK is governed by the Inheritance Tax Act 1984. Very briefly, estates below £325,000 suffer no inheritance tax. However, estates larger than that suffer inheritance tax at 40% on the excess over £325,000. As one might expect there is a complex system of exemptions and relief for certain types of asset, and leaving part of the estate to charity can reduce the inheritance tax on the remainder of the estate. The details are beyond the scope of this chapter.

However, a key point is that provided the spouse is not domiciled outside the UK, IHTA 1984 s18 (1) specifies an unlimited exemption for inheritances passing to a surviving spouse. The impact is illustrated below where a husband dies leaving an estate of £10 million which is allocated in accordance with the Islamic rules of succession.

£3.37 million of inheritance tax is suffered. If instead of applying the Islamic rules of succession the entire estate had been left to the widow, no tax would have been charged. Obviously on the widow’s later death tax may be payable, but that death might not take place for many years.

Mitigation of UK Inheritance Tax Liability

The details of UK inheritance tax planning are beyond the scope of this chapter. However, there are a number of measures which can mitigate the above consequences. For example:

- The husband could hold part of his wealth in the form of assets that suffer a reduced or zero inheritance tax rate, such as business property.

- The husband can give away some of his wealth during his lifetime to those individuals who will inherit in the event of his death. Such gifts are normally exempt from inheritance tax if the donor survives for seven years after the gift.

Other Jurisdictions

Each jurisdiction where the client holds assets needs to be considered separately to consider taxes on death, and also to consider whether any local rules on inheritance might over-rule the disposition the client is planning in his or her will.

Investments

HNWIs will typically hold a range of investments. In conventional finance language, these are likely to include cash deposits, fixed interest securities, real estate, commodities, directly held equities and equity funds, insurance products to provide risk mitigation or to provide tax-favoured investments, and pension products.

Most of the above investment products have Shari’a-compliant variants or analogues. In many cases, depending upon the jurisdiction, the Shari’a-compliant variants may give rise to taxation issues that do not arise with the equivalent conventional product. The broad reason is that the taxation systems of the jurisdictions concerned were developed over an extended period in an environment of exclusively conventional finance. In many cases achieving economic results similar to those of conventional finance but using Shari’a-compliant transactions causes additional tax costs to arise.

In the case of UHNWIs, the wealth management advisor may find himself structuring investment transactions in jurisdictions where Islamic finance has not previously been present and where the jurisdiction’s tax administrators may not have developed any tax rules for the taxation of Islamic financial transactions.

Some examples are given in the discussion below.

Cash deposits

The conventional transaction is straightforward. The client makes a deposit with a bank, either for a fixed period of time at a fixed interest rate, or for an indeterminate time with interest being paid at a rate which varies over time in line with market interest rates.

Most jurisdictions have well-developed tax law covering the taxation of conventional banks, and the taxation of interest earned from banks either by domestic depositors or by foreign depositors.

The Islamic analogue is a profit and loss sharing investment account, illustrated diagrammatically below.

Islamic banks typically offer savings products in the form of profit and loss-sharing investment accounts, which at least conceptually are exposed to the risk of loss but where the customer participates in the profits made by the bank from the use of the customer’s money.

A common contractual form is a mudaraba contract, as illustrated above.

In a mudaraba transaction, the investor (the depositor in the bank) provides cash to the bank (acting as mudarib) to invest that money in a commercial venture, with the bank as mudarib managing that commercial venture. Typically, in the case of a bank the commercial venture will consist of the full range of its operating assets, both finance facilities made available to customers and financial assets held in the bank’s treasury operations to ensure that the bank has sufficient liquidity to repay its current account and savings accounts customers when required.

If there are profits from the bank’s operations, those profits are shared between the bank and the customer on an agreed basis. Typically, the customer obtains a return similar to market interest rates while the bank keeps any excess return as a reward for organising the transactions.

Generic Taxation Issues

The transaction summarised above gives rise to a number of taxation questions. For example:

- What is the nature of the economic return paid to the investor? Should this be taxed as a share of business profits, or as passive investment income?

- Are the payments to the investor deductible for the bank?

- If the investor is located outside the jurisdiction, do the bank’s activities as mudarib (a form of agent) cause the investor to have a taxable presence (normally called a “permanent establishment” in international tax vocabulary) in the jurisdiction where the bank is located?

The Approach of the United Kingdom

The UK first legislated for this transaction in Finance Act 2005, and the law is now contained in Income Tax Act 2007 s564E for the taxation of individuals and in Corporation Tax Act 2009 s505 for the taxation of companies. Very briefly for all tax purposes the bank is treated as paying interest to the investor. Furthermore, the activities of the bank (if located in the UK) are not treated as causing a non-UK investor to have a permanent establishment in the UK.

Fixed Interest Investments

The typical conventional fixed-interest investment is a bond having a specified maturity and a fixed interest rate, issued by either a public authority or sovereign government, or issued by a company. While bonds are not considered to be Shari’a-compliant, over the last fifteen years sukuk has developed as an asset class offering similar economic characteristics, as illustrated below:

The investment goal in the above transaction is for the Investors collectively to provide US$100 million to a company, here called “Owner” for a fixed period of time, say five years, and to receive a fixed annual payment of US$5 million as an economic return. This is achieved by Owner selling a building to a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) owned by a charity, and then renting the building at a fixed annual rent of US$5 million per year. SPV pays for the building by issuing fractional ownership certificates (known as “sukuk”) to the Investors. Each year when Owner pays rent to the SPV, the SPV passes on the rent to the Investors in proportion to their ownership of the sukuk. After five years, the Owner will repurchase the building for US$100 million, which the SPV will similarly pass on to the Investors who own the sukuk.

Generic Taxation Issues

Many taxation issues need to be considered when structuring such a sukuk transaction. For example:

- Is the sale of the property by Owner to SPV and at the expiry by SPV to Owner subject to taxes on capital gains, recapture of tax depreciation previously allowed, or real estate transfer taxes?

- Is the SPV taxable on the rent received? Does it receive a tax deduction for its payment to the sukuk investors?

- Are the payments by the SPV to the Investors subject to withholding tax? If they are, do the jurisdiction’s double taxation treaties apply to such payments?

- If an investor sells his holding of sukuk to a new purchaser, what is the nature of that transaction?Is it treated as the sale of a fractional interest

- in the building and therefore subject to the jurisdiction’s real estate transfer tax?

United Kingdom Approach

Subject to compliance with some tightly drawn legislation in Finance Act 2009 Sch61, the sale by Owner to the SPV and by the SPV back to the Owner are disregarded for the purposes of the taxation of capital gains, recapture of tax depreciation and the UK’s real estate transfer tax which is called Stamp Duty Land Tax. The SPV suffers no tax costs as its receipt of rent is matched by tax relief for its payments to the Investors. The Investors are taxed as if they held an interest-paying security; thereby ignoring the legal form of the transaction which is a fractional ownership interest in the building.

The overall consequence is that the UK treats the sukuk transaction in basically the same way as it would treat Owner issuing an interest-paying bond to the Investors. Furthermore provided the sukuk is listed on a stock exchange, it should be treated for withholding tax purposes in the same way as a Eurobond, so no UK withholding tax should be suffered.

Leasing of Assets

For HNWIs, the wealth manager may be engaged in structuring leasing transactions over assets such as shipping containers, aeroplanes or real estate, either as a way of synthesising investments paying a fixed rate of return or as a way for the investor to have full economic exposure to the assets concerned.

The leasing of such assets normally constitutes a business. Accordingly taking into account the location of the investor, the assets and the wealth manager, it is important to be aware of the risk that the wealth manager’s activities on behalf of the (foreign) investor may cause the investor to have a taxable presence in the country where the wealth manager is based and where the wealth manager enters into the leasing transactions on behalf of the HNWI.

Each jurisdiction will have its own rules to determine what kind of activities by an agent (the wealth manager) cause the principal (the HNWI) to have a taxable presence for business tax purposes, and many countries will have an exemption for the activities of investment managers. However the detailed legislation needs to be kept under constant review on a country-by-country basis.

Collective Investment Schemes

UHNWIs will normally own their investments directly, either making their own investment decisions or hiring the services of an investment adviser. However, less wealthy individuals will often use collective investment schemes as a more cost-effective way of achieving investment diversification combined with professional investment management.

Accordingly, Islamic wealth managers need to be equipped to select from the universe of available collective investment schemes, and may even find themselves creating new collective investment schemes to meet clients’ needs.

In conventional finance, collective investment schemes (using the definition in its general sense) cover a very wide range as illustrated below:

- Money market funds – collectivising short-term deposits and short-term commercial paper.

- Bond funds – collectivising fixed-interest investments.

- Equity funds – collectivising the ownership of shares.

- Commodity funds – collectivising the ownership of physical commodities.

- Venture capital funds – collectivising investment in early-stage businesses.

- Private equity funds – collectivising investment in leveraged buyouts.

- Hedge funds – collectivising aggressive investment strategies such as short selling.

Some of the above are straightforward to set up in a Shari’a-compliant way. For example, the main requirements for a Shari’a-compliant equity fund is selecting shares that themselves are Shari’a-compliant and making suitable arrangements for the holding of cash awaiting investment. Others, such as hedge funds, are more challenging, although there are some providers offering Shari’a-compliant versions.

Taxation of Collective Investments Schemes Generally

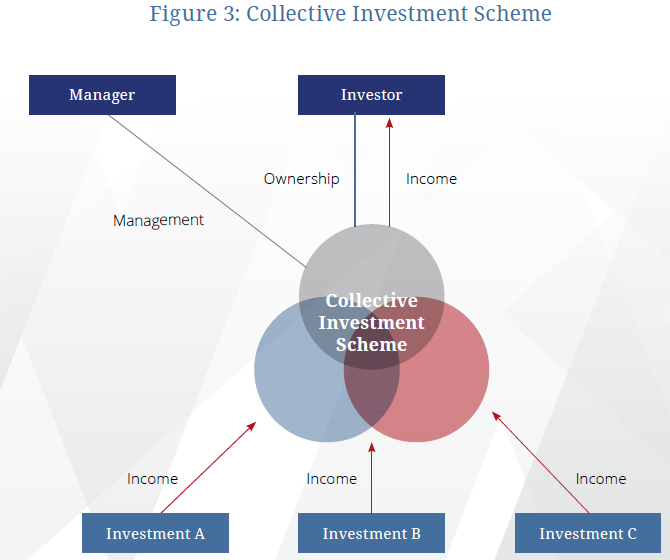

A generic collective investment scheme is illustrated below.

The investors will typically be located in multiple jurisdictions. It is commonplace for non-US investment managers to exclude US individuals from becoming participants of collective investment schemes due to the onerous regulatory and tax rules imposed by the USA. Apart from this, investment managers will typically have no control over who becomes an investor in the collective investment scheme, and must assume that they are located in multiple jurisdictions.

The domicile of the investment manager will typically be chosen taking into account a combination of non-tax factors (political stability, the regulatory environment, availability of banking, legal, taxation and custody services, etc.) and taxation factors (the tax treatment of the individuals who work for the investment manager, the taxation of investment management companies etc.).

The domicile of the collective investment fund itself depends partly on regulatory issues and partly on taxation issues.

From a regulatory perspective, the European Union (EU) is a very large market. Once an investment fund is certified as complying with EU Directive 2009/65/EC of 13 July 2009 on the coordination of laws, regulations and administrative provisions relating to undertakings for collective investment in transferable securities (commonly known as UCITS IV): it can be marketed throughout the EU. Perhaps even more importantly qualifying under UCITS IV is often regarded by investors located in other non-EU jurisdictions as an indicator of quality. Accordingly, even investments primarily targeted at non-EU investors may be structured to be UCITS IV compliant.

The choice of domicile for the collective investment fund requires striking a balance between two objectives which will often conflict:

- The desire to avoid taxation inside the collective investment fund. It is clearly undesirable for the collective investment fund to suffer taxation on gains when it buys and sells investments. Similarly it is desirable to choose a location which does not tax income received by the collective investment fund.

- The underlying investments, here Investment A, Investment B, etc. may be located in many jurisdictions. Those jurisdictions will typically levy a withholding tax on income paid to the collective investment fund. If the collective investment fund is located in a low-tax or zero-tax jurisdiction (a “tax haven”) then the jurisdiction where the investment is located is likely to apply its maximum withholding tax rate. A collective investment fund located in a tax haven will not be able to benefit from any reduced rate that the paying jurisdiction may allow under its double taxation treaties.

UK Taxation of Collective Investment Schemes

As one of the world’s leading financial centres, the UK has a fully developed regime for the taxation of collective investment schemes. For brevity, this chapter discusses only the taxation of authorised (authorised and regulated under the terms of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000) open-ended (schemes where new interests are created or cancelled in response to investor demand, so that the price per ownership unit always corresponds to net asset value) collective investment schemes, namely authorised unit trusts and open-ended investment companies. The following comments summarise the basic principles the UK follows.

The collective investment scheme itself is taxed as if it were a company but with specific variations. Of these, the most important is that the collective investment scheme is not subject to tax on capital gains. That allows it to sell and buy investments such as shares or real estate without suffering tax. Otherwise, there would be a risk of the capital gains being taxed twice: once when the collective investment scheme sold the asset, and a second time by taxing the investor when he sold ownership units in the scheme, since the value of those ownership units would have been increased by the gains made by the fund.

Collective investment schemes are not subject to tax on UK source company dividends, and such income when distributed to investors is taxed in their hands in the same way as company dividends. With regard to dividends from overseas, the UK has one of the world’s largest collections of double taxation agreements which helps to minimise the impact of withholding tax in the overseas countries from which dividends are paid to the UK.

Collective investment schemes are subject to tax on interest income, but receive a deduction for interest distributions to investors which effectively cancels out the tax liability of the scheme leaving the investors taxable on the interest distribution.

The UK typically taxes UK resident investors on the income they receive from collective investment schemes, and charges them with capital gains tax when gains are made from selling ownership units in the collective investment scheme. However for certain types of non-UK collective investment scheme, if the scheme does not have the appropriate status with the UK tax authorities, (it needs to be a registered “reporting fund”) gains made from selling ownership interests will be treated as ordinary income which is subject to tax at a higher rate than capital gains. The provisions are too complex for further discussion in this chapter.

UK tax law specifically provides for the taxation of Islamic financial instruments by specifying that income from investments that qualify under the “alternative finance arrangements” provisions (the UK’s tax code for Islamic finance) are treated as interest-paying investments for taxation purposes.

Concluding Comments

In wealth management, it is always essential to keep in mind the taxation provisions of three jurisdictions:

- The country where the underlying assets are located. This country is likely to charge withholding tax on payments of income out of the country, and may charge tax on gains made on the sale of assets located in that country.

- The country where the wealth manager is located. This country’s rules need to be monitored to ensure that the activities of the wealth manager do not cause the investor (if not resident in that country) to have a taxable presence in the country. Furthermore, if a collective investment scheme is created in that country, (or in another country), the taxation of the collective investment scheme itself needs to be analysed.

- The country where the investor is located

This country is likely to tax income received by the investor and gains made from selling investments. Furthermore, some countries have relatively penal tax codes applicable to certain types of collective investment scheme. For example the UK’s treatment of non-UK collective investment schemes which do not qualify as registered reporting funds.

Accordingly, the merits of any form of wealth management strategy need to be assessed on a post-tax basis, requiring detailed consideration of the applicable tax rules in addition to considering the investment merits of the proposals.