This chapter explicates the issue of factors affecting Islamic wealth in the Muslim countries, discussed in Chapters 1 & 5 in a methodological context. The reference here is to the prices of oil – a commodity that wealth accumulation in a number of Muslim-majority countries. Petrodollars are also assumed to have a direct link with the growth in Islamic banking and finance. Therefore, this chapter has huge relevance to the understanding of dynamics of Islamic wealth management.

The idea of a link between oil prices and Islamic wealth would seem to make intuitive sense given the prominence of oil producers among the countries characterized by sizeable Islamic populations. This connection is particularly obvious in the case of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) member states, which are all oil exporters and include one-third of the

12-country membership of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) – Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Kuwait, and Qatar. OPEC recently announced that Indonesia would rejoin the organization in December. Indonesia is not treated as an OPEC state in the current analysis. Overall, a majority of OPEC members are predominantly Islamic countries. In addition to the GCC members, these include Algeria, Iran, Iraq, Libya, and Nigeria (roughly 50% Islamic). Kazakhstan is another one of the top 20 oil producers globally with a predominantly Islamic population.

The connection between Islamic populations and Islamic wealth, of course, is not direct. After all, only a fraction of the global Muslim population make use of Islamic finance, although the figure is expected to rise. Moreover, some of the key oil producers now have much higher levels of penetration of Islamic finance than others. The GCC countries, which have – along with Malaysia – been at the forefront of developing the Shari’a-compliant financial industry, head the list. According to estimates made by the Islamic Bankers Association and Edbiz Consulting, the aggregate size of the Islamic banking and finance industry has grown from US$639 million to US$1,984 billion between 2007 and 2014. The Islamic oil producers with the largest Islamic finance sectors in 2014 were Iran (US$530 billion), Saudi Arabia (US$339 billion), the UAE (US$144 billion), Qatar (US$111 billion), Kuwait (US$107 billion), and Bahrain (US$27 billion). The list of the ten largest Islamic financial sectors includes four oil net importers – Malaysia (US$249 billion), Turkey (US$69 billion), the UK (US$43 billion), and Indonesia (US$49 billion). The combined Islamic finance industry of all other countries is worth US$316 billion. With the exception of Iraq (US$13 billion) and Brunei Darussalam (US$12 billion), these countries are not significant oil net exporters. In aggregate terms, therefore, oil net exporters accounted for a total of US$1,283 billion of Islamic assets, or just under two-thirds (64.7%) of the total. Of course, the performance of some of these Islamic financial sectors is not purely linked to domestic growth drivers as they also attract significant inflows from other economies. Hence, for instance, Islamic asset managers in London or Malaysia are likely to benefit from oil-induced increases in wealth in other economies.

Identifying the Links Between Oil Prices & Islamic Wealth

A number of factors influence the relationship between oil prices and Islamic wealth. Chief among them are the following:

Current Account Position Higher oil prices boost the current account positions of oil exporters. This increases the wealth of the sovereigns, which almost invariably derives a substantial proportion of their revenue from oil exports in these countries. According to estimates by the Institute of International Finance, the total foreign assets of the GCC countries rose five-fold between 2001 and 2011 alone, from US$0.5 trillion to US$2.5 trillion. In practice, the main beneficiary institutions tend to benefit either the sovereign wealth funds of these countries or the central bank reserves.

The sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) of the GCC economies (along with their counterparts in other economies with similar profiles) have seen a substantial build-up in their holdings during the recent years of high oil prices. The total assets of sovereign wealth funds globally rose by a record US$1 trillion in 2014 to a total of US$7.1 trillion. According to the Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute, some US$4.3 trillion of this total is dependent on oil and gas. Following an estimated 12% average annual growth in their assets over the past five years, SWFs are expected to see a deceleration to 4% this year as a result of the recent oil price correction.

Of course, not all, or indeed even most, of the holdings of SWFs have gone into Islamic assets but it seems safe to assume a positive correlation between the two. This is partly due to the increased domestic and emerging market bias of these and other institutions, which is likely to have benefited Islamic assets more than their traditional profile which was heavily skewed toward the West. For instance, leading GCC SWFs appear to have significantly boosted in-house assets management during the global economic crisis. Other things equal, this is likely to result in at least a somewhat greater focus on local and regional assets in countries with relatively developed Islamic finance industries. For instance, the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA) this year announced that it would handle more of its investments in-house. The proportion is already estimated to have risen from 25% in 2013 to 35% in 2014. The Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA) has reportedly taken similar steps and has, among other things, set up a unit to invest in infrastructure. Such a focus is likely to increase relative exposure to Islamic economies and assets, not least due to the major infrastructure boom underway in the GCC. Many of the Islamic financial institutions in the region are active players in the process.

If high oil prices are a key driver of wealth creation in many oil-exporting economies, the opposite is naturally also true. We have repeatedly seen a pattern where lower oil prices have substantially reduced transfers to SWFs and in a number of cases led to net transfers back into government coffers. Many sovereign funds posit a minimum oil price below which transfers from the government to the SWF are no longer made. Similarly, many countries have introduced provisions for governments to claim a percentage of the annual receipts of SWFs. A recent example in point of this dynamic is Saudi Arabia which in March reported a 4.7% YoY drop in its net foreign assets to US$691 billion, a level was last seen in July 2013. In 2008-9, lower oil prices are estimated to have reduced the aggregate value of SWFs globally by US$150 billion to US$4 trillion.

Following an estimated 12% average annual growth in their assets over the past five years, SWFs are expected to see a deceleration to 4% this year as a result of the recent oil price correction.

Lower oil prices tend to have a benign impact on net oil importers. However, their weight among the main centers of Islamic finance is less than that of oil exporters. Moreover, the link between the current account position of these economies and the oil price tends to be much less strong than it is among the leading oil exporters. While oil may be an important import, it tends to be one of many. Moreover, the connection between the current account position and sovereign wealth is typically much less direct.

Fiscal Implications

There has traditionally been a clear positive correlation between the oil price and government spending in most oil-exporting economies. For instance, in the GCC, government sectors are historically quite large and primarily funded from oil exports. Under this model, higher oil prices typically trigger increases in government spending. In the case of recurrent spending, this tends to benefit public sector salaries and benefits, thereby boosting the savings and disposable incomes of citizens. In the case of capital spending, such increases create multiplier effects through sectors such as construction and finance. In either case, the impact on private wealth creation is positive.

Government spending tends to be subject to a ratchet effect so that lower oil prices typically contain the growth of government spending in these oil-dependent fiscal systems (barring countercyclical efforts), rather than actually reducing it. Hence, the impact of oil price increases on sovereign and private wealth is likely to be much greater than that of oil price decreases.

Oil importers usually have fiscal systems that are less influenced by the oil price, although higher oil prices normally exert a negative effect on overall economic activity. Hence, lower oil prices should produce a positive wealth effect and boost the disposable incomes of the population.

Indirect Effects

Higher oil prices tend to have a range of positive indirect effects in oil-exporting economies. They generally boost liquidity, enhance economic confidence, and encourage spending and investment. Conversely, oil price corrections tend to undermine confidence and increase both investor and lender caution. The 2008-9 crisis in the GCC serves as an extreme example of a global crisis having a major adverse effect on private wealth through disruptions that both depressed the oil price and hit the regional asset markets.

In oil-importing economies, the opposite tends to be true. Lower oil prices boost the external position and disposable incomes. They generally tend to have a positive impact of investor and consumer confidence.

In practice, of course, a multitude of factors can underpin oil price variations and these causal factors can be much more important in determining the overall economic impact than oil price dynamics in isolation. Weak oil prices can be the result of weaker demand for oil. To the extent that this is consequence of weaker aggregate demand, the stimulating effect of lower oil prices even in importer nations is likely to pale in comparison to the broader economic malaise.

Similarly, oil prices tend to be inversely correlated to the US dollar. The recurrent speculation in recent years of US tightening has engendered period of dollar strength which have typically thrown up a multitude of challenges for oil import-dependent emerging markets. Especially in countries with current account vulnerabilities, this tended to translate into capital outflows and downward pressure on the currency which has often forced monetary policymakers to react through tightening. In some markets, this downward influence of lower oil prices inflation has, by contrast, allowed central banks to stimulate economic activity through monetary loosening.

Oil is Only Part of the Story

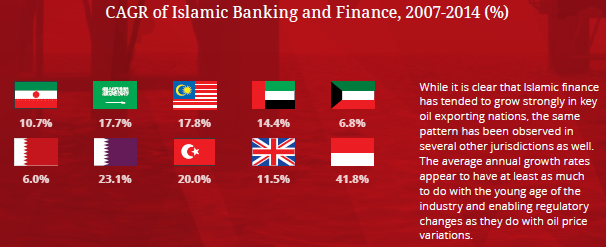

While oil is an important driver, especially of sovereign wealth in key Islamic economies, the development of Islamic finance has been influenced by a multitude of factors, such as regulation, convergence, and diversification. Many of them are largely independent on oil prices. Islamic finance is a relatively young industry and is still typically amidst a relatively early stage of convergence-style extensive growth. For instance, countries such as Oman and some of North African economies are seeing strong growth in Islamic assets now that regulation has explicitly permitted – typically fairly recently – Shari’a-complaint structures and products. For instance, Oman was the last GCC economy to adopt formal regulations for Islamic finance in 2011 and has since then issued two Islamic banking licenses. Sub-Saharan Africa is beginning to see more and more activity in Islamic finance and is generally viewed as having significant potential for rapid growth in this area. New growth from a low base is also materializing in countries ranging from the former Soviet Union to China and India. Developing largely from scratch, Islamic finance in these countries is still to an extent driven by pent-up demand as people switch to their preferred option which has now become available or develop a better sense of the new offerings.

While oil is an important driver, especially of sovereign wealth in key Islamic economies, the development of Islamic finance has been influenced by a multitude of factors, such as regulation, convergence, and diversification.

Islamic finance is also benefiting from new investors or deliberate diversification by existing investors looking for new types of exposures. For instance, the growth of the takaful industry as an alternative to conventional insurance has created a growing class of institutional investors that can only invest in Shari’a-compliant assets. In many countries, they are likely to experience strong growth due to favourable demographics, new regulations, or internationally low insurance penetration levels which are expected to grow swiftly. Pension, social insurance, and provident funds in many economies are growing rapidly and become increasingly active as investors in Islamic assets. They are typically at an early stage of their growth trajectory in countries with the largest Islamic financial sectors. In some cases, the global economic crisis enhanced perceptions of Islamic finance as a safer alternative due to its principles-based nature and strong aversion to leverage. This has strongly stimulated interest also among conventional institutions and investors.

Of course, one important driver behind the growth of Islamic wealth has been the concentration of Islamic finance in rapidly growing emerging economies. Both the GCC and South East Asia, as well as economies such as Turkey, have benefited from growing investor interest as institutions and even individuals have sought to diversify their assets and to enhance their returns at a time when yields in the West have been at historically low levels. At the same time, many of these “Islamic” markets have benefited from greater integration in the global economy as well as easier access as a result of better technology, improving regulation, and more attractive products. In the GCC, for instance, the exchanges of the UAE and Qatar are now included in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index which should drive new inflows of institutional money. Saudi Arabia this year made it possible for qualifying foreign institutions to invest directly on Tadawul. Such steps are likely to stimulate interest in the Middle East and North Africa wider region as well.

Similarly, the growing sophistication and increased product offering of Islamic financial institutions is likely to increase their relative appeal ad competitiveness vis-à-vis conventional players. For instance, Bahrain has for several years seen much faster growth in Islamic finance than in conventional finance.

Supply-side Indicators

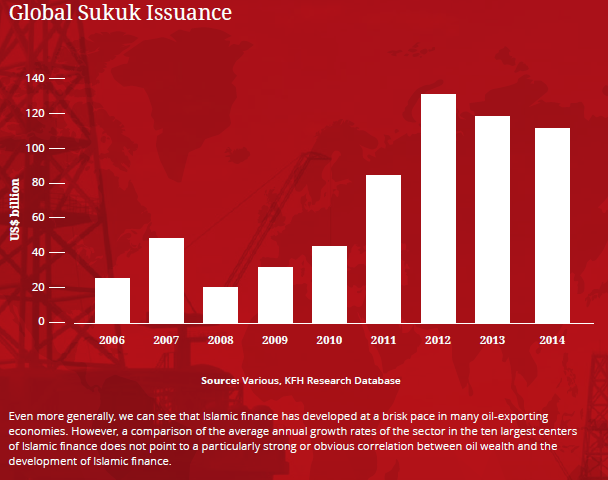

Growing Islamic wealth is likely to have been an important driver in stimulating increased activity in Islamic products, such as sukuk. While sukuk issuance has benefited from increased standardisation and a growing pool of experience, the attractiveness of the asset class has also reflected strong pent-up demand. The favourable terms available in the assets class appear to have induced many issuers to opt for sukuk rather than conventional bonds in recent years. For instance, GCC institutional investors have been very active in buying sukuk, which remain one of the easiest ways of gaining exposure to leading government-related or blue-chip corporate issuers. Access to this asset class has further benefited from a growing number of sukuk funds.

Evaluating the Data

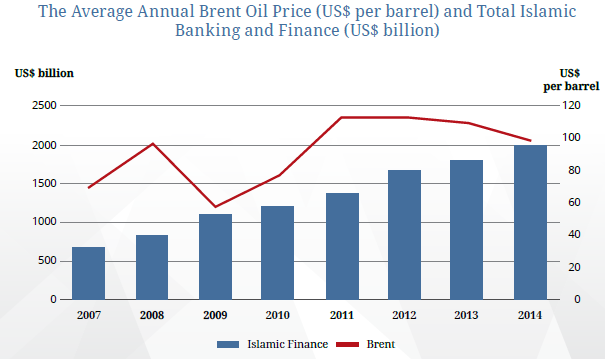

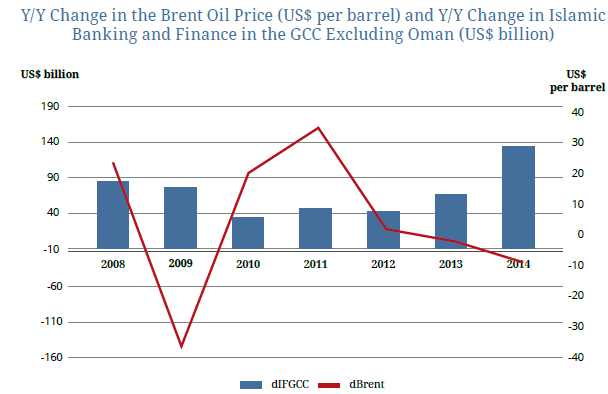

Both conceptually and on the basis of a great deal of anecdotal evidence, we would expect to see a relationship between oil prices and Islamic wealth. What does the available data tell us? Below is a comparison of the dynamics of the Brent benchmark price for oil with the data on the size of Islamic finance as compiled by the Islamic Bankers Association and Edbiz Consulting for Global Islamic Finance Report 2015. Any meaningful statistical analysis of the data is complicated by a host of methodological issues, not least the shortness of the series. What is presented below, therefore, are merely indicative high-level snapshots.

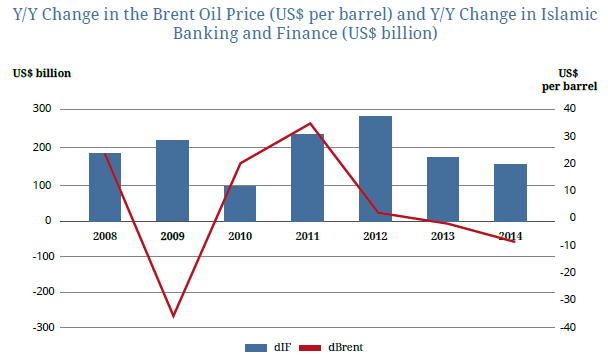

What we can observe from a direct comparison between the size of the Islamic banking industry and the oil price is something of a study in contrasts. While oil prices throughout the period under review have remained at a historically high level, they have experienced considerable volatility. The 2008-2011 cycle is particularly pronounced and something of replay is being observed since late 2014. On the other hand, Islamic finance globally has continued its steady onward march with limited disruptions, even if the pace of growth has varied somewhat. This contrast becomes even more evident from a comparison of year-to-year differences during the period.

In this case, a tentative relationship can be observed more clearly. In general, a drop in the oil price has tended to be followed by a deceleration in the growth of Islamic finance. A precipitous oil price correction in 2008-2009 was followed by a slowdown in the growth of Islamic finance from an annual increment of 25.6% in 2009 to a much more moderate 10.1% in 2010. Another deceleration in the pace of growth became evidence in 2013 as oil price growth once again turned negative. Islamic finance expanded by 20.3% in 2012, but this pace subsequently dropped to 11.0% in 2013 and 9.4% in 2014. To the extent that it is possible to extrapolate from this pattern, we would almost certainly expect to see a further pronounced slowdown in 2015 as the average annual oil price is likely to be markedly below the just under US$100 per barrel seen in 2014.

Somewhat paradoxically, limiting this analysis to the GCC countries produces a strikingly different picture.

The GCC countries, of course, along with Malaysia, have been at the forefront of developing Islamic finance while also being significant oil exporters.

The graph suggests that the oil price correction in 2008-2009 was followed by a much more long-lasting slowdown in the growth of Islamic finance in the GCC than was the case globally. This is likely to be at least partly linked to the systemic impact the onset of the financial crisis had on regional real estate markets as well as the incipient sukuk market. Many Islamic financial institutions had heavy exposures to real estate and had been instrumental in driving the growth of the market prior to 2008. This dynamic was reversed when the market was hit by as sharp correction, most notably in the case of the UAE. Concurrently, regional financial regulators took a number of steps to weaken the link between the financial sector and real estate in order to manage systemic risks.

A drop in the oil price has tended to be followed by a deceleration in the growth of Islamic finance.

In contrast to the global Islamic finance industry, the sector in the GCC has not been hit at all to date by the reversal in oil price growth since 2013. This is likely partly reflective of the success in putting Islamic finance in general, and the regional sukuk markets in particular, on a sustainable growth path since the 2008 crisis. Moreover, some of the regional financial sectors also benefited from inflows of deposits and investments from other parts of the Middle East during the “Arab Spring”. The recent dynamics of the sector appear robust and it can likely be expected to display considerable resilience in the face of the current oil cycle. Nonetheless, matching the 22.8% growth seen in 2014 is likely to be a tall order.

Concluding Remarks

Firm conclusions of links between oil price variations and the development of Islamic finance are complicated by the fact that the Islamic finance industry remains relatively young. It is still experiencing robust convergence-style growth, both as a result of its growing geographic footprint and thanks to its increasing maturity and sophistication. This in turn tends to translate into new and better products as well as growing suite of services, partly as a result of more and better-enabling regulation, and the growing willingness of new institutions to develop their offerings in this space. Nonetheless, as numerous as the qualifications overshadow this analysis are, it seems fairly clear that oil prices both have been, and will remain one of a number of key drivers of the development of Islamic finance, in particular in countries where oil is an important part of the economy.