Introduction

Nearly all activities labelled today as “Islamic asset management” or “Islamic wealth management” are not at all related to their conventional cousins. Islamic asset management is primarily a supply-side phenomenon, driven by Shari’a compliancy and related Shari’a premium (higher management fees charged by the Islamic fund managers). Sometimes it is accused of being random, undisciplined, and lacking professionalism, but there is certainly a distinct improvement as evidenced by many Western fund managers in Islamic fund management.

The Shari’a premium-based argument assumes that investors are looking for Shari’a compliancy only and may not in fact attempt to seek to improve their chances of achieving long-term savings objectives through disciplined investing. Instead they randomly purchase investments from their bankers who offer Shari’a compliancy with the help of their Shari’a boards. By extension the theory assumes Muslim investors may not be interested in planning and executing an investment savings program based on modern, global investment practices, instead assembling a hodge-podge of investments in a haphazard fashion.

While this approach has worked in favour of the Islamic fund and asset managers in the past, this however is not appealing to a vast majority of new users of Islamic asset management services, many of those may have advanced university degrees, communicate in many languages, or run complex businesses. The younger generation of Muslims care deeply about Islam in all aspects of their lives, including their investments. This newly emerging trend requires change in Islamic asset management styles and the underlying fund management practices, which must not only be Shari’a-compliant but also generate risk/return profiles commensurate with their conventional counterparts. The conventional asset managers who have been involved in Islamic finance seem to resist this new trend, believing that the new trend is limited to only a very small proportion of Muslim investors. Many such asset managers have surprisingly suggested that:

- Our Muslim clients don’t want Islamic investing

- Our bank tried one Islamic equity fund and because it didn’t sell we know Muslims don’t want Islamic investing

- Our bank won’t go into an area of investing we don’t understand

- In our experience it won’t work

- Our capital-guaranteed structured products sell so well we don’t want to change the product mix for Muslims

- We’re afraid to sell Islamic asset management to existing Muslim clients

These excuses are surprising as the basic genetic coding of Muslims is presumably identical to the rest of the world’s population. Universal human values, including the need to organize and execute savings plans, should be the same for Muslims as they are for anyone else. These same asset managers prefer to offer everyone else (Brazilian ranchers, Italian industrialists, Australian artists, California pension funds, etc.) wealth and asset management services derived from a disciplined, professional and well-established process.

It is mistakenly thought that the old asset management model only applies to Muslim markets, not to those in, for example, Brazil, Russia, the United States, Germany, or China. In those markets we know that most banks approach potential clients with a very specific service offering: “We will manage your assets according to the principles of Modern Portfolio Theory, matching your investment profile with an investment strategy and a pool of carefully diversified investment products that will have a high chance of achieving your investment objectives.” Seemingly this is the global standard, which must be applicable to Muslim investors who seek Shari’a-compliant investing.

Foundations Of Asset

As has been detailed elsewhere, Modern Portfolio Theory forms the bedrock of asset management everywhere, and should by any measure form the bedrock of Islamic asset management. This was first conceptualized in 20092, showing how first an asset manager examines a particular client’s profile—whether the client is an individual or an institution—deriving from that a roadmap for investing. The client profile quantitatively and qualitatively describes the client’s investment objectives by indicating risk and reward preferences, defining end-term investment objectives, and shows current and future assets and liabilities.

From the client profile one can choose an investment strategy that has a certain probability of achieving the client’s investment goals. There are only three kinds of strategies: Income, Balanced and Growth, indicating low-, medium- and higher-risk investing styles. All other strategies are derived from these and only these three.

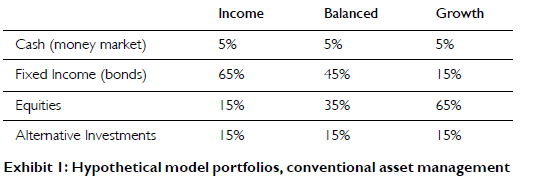

An investment strategy is then matched with an asset allocation model, where there are only four categories of assets: Cash (money market), Fixed Income, Equities and Alternative Investments (being any asset that is not in the first three categories)3. These categories are themselves reflective of risk, where Cash and Fixed Income are relatively less risky, and Equities and Alternative Investments inherently riskier. More risky assets means more risky portfolios, and vice versa.

Asset allocation models are critically important as numerous attribution analysis studies have shown repeatedly, that investment success or failure normally evolves from the macro decisions made by the asset manager, not micro decisions. Macro in this sense means not whether to buy Nokia or Motorola, and not whether to buy on a Monday and sell on a Friday. Security selection and investment timing have been shown to be almost insignificant to investment performance.

Instead, the larger decisions on whether to move porrelated among professional asset managers. Typically the three investment strategies invested in the four asset categories come up with allocations as shown in the Exhibit 1.

While the above is a somewhat crude depiction of the three investment strategies and their composition of four asset categories, it is in fact illustrative of how professional managers actually do make investment allocations for real-world clients everywhere.

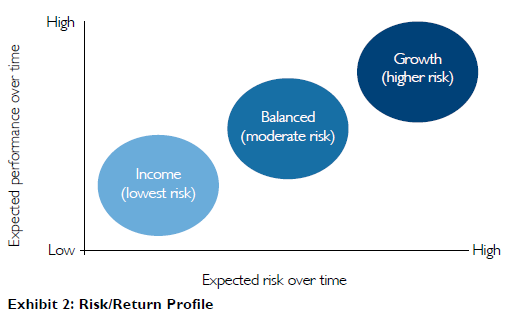

This is intuitively correct. One doesn’t need an advanced degree in statistics to understand that expecting higher rewards will involve higher risks, and vice versa. Nor does one need professional qualifications to conclude concentration of investments into one or a few assets is inherently more risky, and that diversification is inherently less risky. We illustrate the risk-reward ratio and its meaning for portfolio investment strategy selection in Exhibit 2.

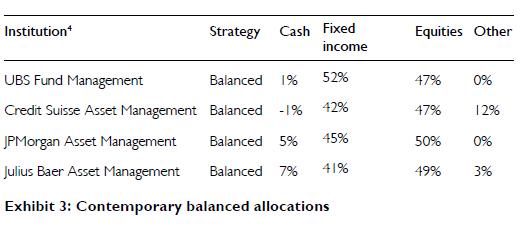

As an indication of what this means in the real world, take a look at contemporary Balanced allocations made today by well-respected names in the asset management industry This can be seen in Exhibit 3.

There are general correlations among all asset managers in all investment strategies, where asset allocation is the result of disciplined, studious analysis of expected future risks and rewards among the four major asset categories.

Foundations of Islamic asset Management

Modern Portfolio Theory is known to underpin all professional asset management everywhere and it should not be an exception for Muslim clients seeking Shari’a- compliant investing. In the above-referenced work5, it was shown that that there is essentially no difference between conventional asset management and Islamic asset management—whether the client is an individual or an institution—except in security selection in compliance with Shari’a. The common, universal steps of the professional practice we call asset management are: 1) client profiling, 2) investment strategy selection, 3) asset allocation, 4) security selection, and 5) investment monitoring and rebalancing. Only at Step 4, security selection, does Islam enter the equation. All other steps are identical for all clients, regardless of faith. Even security selection is nearly identical, the only difference being the selection of high-quality, qualifying assets that have an acceptable degree of Shari’a-compliance.

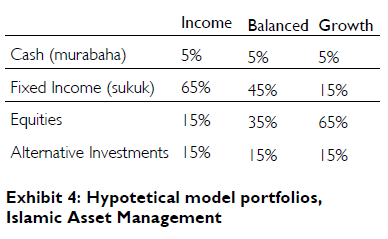

Fortunately, the Islamic banking community has delivered what we believe is a minimum number of mutual- fund securities that are in fact fully Shari’a-compliant and represented in all four asset categories. Each asset category has a Shari’a equivalent: murabaha or trade finance funds for Cash, sukuk or trade finance funds for Fixed Income, Shari’a-compliant shares for Equities, and numerous “other” securities such as real estate funds or commodity funds for Alternative Investments.6 Therefore, one can conclude Shari’a-compliant investing would comprise the identical three investment strate- gies and four asset categories common in conventional investing. General allocations can be seen in Exhibit 4.

Shari’a-compliant funds universe

It should come as no surprise that Muslim investors are identical to people of all faiths in their need for planned, disciplined savings. Such common human characteristics and behaviours are not exclusive to any race, ethnic class, or faith. They are universal. Among them is the need to save for the future, itself not a spiritual activity.

To do this, one must examine security selection, the only element of the common rules of professional asset management that requires adaptation to Shari’a. Focus should be on the universe of Shari’a-compliant assets to determine just how many investment funds meet global standards. The question is: can an asset manager assemble a professional portfolio of Shari’a-compliant assets that will meet international asset management standards yet at the same time satisfy the spiritual component of a client’s investment objectives?

No asset management of any kind can be done without data tools. These data tools are found in abundance in the conventional world of asset management. They include Bloomberg, Reuters, Morningstar, IdealRatings, Eurekahedge and many others. In fact, each of these mentioned services have Islamic components, databases that presumably fill the needs of professional investors for information on securities available in the Islamic as- set universe.

Unfortunately, on more careful examination it is found that none of these services meet professional standards for asset managers seeking to fulfil the majority of Islam- ic investment mandates. All of them have incomplete listings of the available universe of Shari’a-compliant securities mostly suited for the average investor, and even most wealthy investors. All but the highest-net-worth investors would find the existing listings of Shari’a-com- pliant securities unusable for constructing diversified portfolios in all asset classes.

Importantly this is so because the large majority of investing is done on a funds-of-funds basis. That means most allocations are made from an assembly of funds, where each asset category in every investment strategy is populated with funds, not individual securities like stocks or bonds. When witnessing actual allocations in the Swiss private banking industry, for example, there are almost no cases of “smaller” accounts being invested directly into individual securities such as stocks or bonds. Smaller is often measured in the tens of millions of dollars.

Exhibit 4: Hypotetical model portfolios, Islamic Asset Management

These allocations are essentially immutable, i.e., if an as-set manager wishes to accept an investment mandate from a Muslim client seeking Shari’a-compliant invest- ing, then the asset manager will construct a portfolio allocation essentially along the same ratios used for any other client with the same client profile. Tolerance for risk and expectations for reward are inherent elements of professionally constructed allocations. lars, where a client account of say USD 50 million or less is considered “small.”

While the threshold of “small” will vary from bank to bank, or manager to manager, the concept is the same:

1) managers cannot dedicate cost-effective individualized investing to every client account, and even less so for smaller accounts, 2) most investment failure or success is not based on individual security selections but on broader investment decisions that can be achieved with funds-of-funds allocations, and 3) resources at all asset management units—whether in banks or investment companies—are limited, so that no manager can be said to be professionally competent in all asset markets all the time, therefore stimulating the need for managers of specialized funds.

Funds-of-funds allocations predominate in the asset management universe. Even very large multi-billion dollar pension funds and endowments utilize funds for much of their allocations. Very few very large investors, in fact, will buy straight securities for all of their allocations. With over 3 million investible securities world-wide it is no wonder that mutual funds dominate the asset management allocation process. Specialization in various geographies, industries and securities is much sought after in the investment world, and nearly always via mutual funds.

And, the universe of conventional funds is rich and large. As of the end of 2009 there were somewhere around 65,000 mutual funds worldwide according to the Investment Company Institute Factbook.7 These funds manage collectively around USD 23 trillion in assets, one of the largest pools of managed money anywhere. A very large number of these funds are identified by the major data sources (e.g., Bloomberg, Reuters), with substantial data on each fund’s history, volume, domiciliation, liquidity terms, and much more. Clearly this eases the professional responsibility of an asset manager seeking a universe of conventional funds for selection and investing into a client allocation.

But what of the Islamic mutual fund space? As was de- tailed previously in the Global Islamic Finance Report 2010, the Shari’a-compliant universe consists of a trifling 830 mutual funds and ETFs and about USD 82 billion in assets under management. Other studies have indicated the Shari’a-compliant universe is even smaller, with about 750 funds managing only around USD 52 billion in assets.8 A global search today would likely show about the same, or perhaps even less. By either number of funds or assets under management, the Islamic funds universe is indeed very small; with Shari’a-compliant funds numbering only 1.3% of their conventional cousins, and only 0.36% in assets under management compared to the global funds universe.

And, a majority of Islamic funds is not available to professional investors simply because they don’t meet professional standards. Typical screening and filtering— based on track record, domiciliation, liquidity and assets under management—reduces that number to substantially less. Adding a Shari’a filter, where funds without acceptable Shari’a compliance are eliminated, brings the total number of professionally acceptable Islamic funds to 99, comprising around USD 30 billion in total assets.9

With only 99 funds in an investment universe and only USD 30 billion in managed fund assets, one must ask: can we achieve professional investment management for clients seeking Shari’a-compliant investing? The short answer is yes, of course we can. In fact, one could conclude we have a professional responsibility to meet our client demands for professionalism, global standards and Shari’a compliance. If there is a path to achieve these goals then there is neither excuse nor reason for not achieving these goals.

Construction of Islamic portfolios

Shari’a-compliant funds were small and few prior to 1999 when Shari’a screening methodologies like those of Dow Jones and FTSE got global recognition. Since then, they are growing fast in size and number. The net new number of mutual funds in 2007, for example, was over 160. Later, with the global financial crisis, that number dwindled to the point where only two new funds were added to the Islamic investing universe in 2009.

GIFR 2010 used screening and filtering techniques common in asset management—with the addition of a Shari’a-compliance screen—and then prepared what are believed to be the first-ever asset allocation models comprising entirely of Shari’a-compliant assets. This process was described in great detail, thus perhaps pioneering the field of what is called Islamic wealth and asset management.

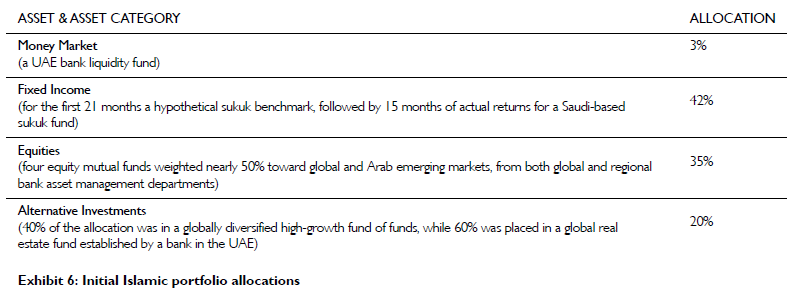

The above allocation was reasonably diversified, including investing in all four asset categories. It was also generally aligned with the Balanced investment strategy portfolios produced at the time by major global asset managers. Unfortunately, upon further testing it was determined the initial allocations were weak in some of the key criteria used to filter and sort qualifying investment funds, as well as diversification weakness (concentration risk). One weakness was the use of a proxy for Fixed Income during the majority of the time period results were measured. Another was the overweighting of global and Arab emerging market equities.

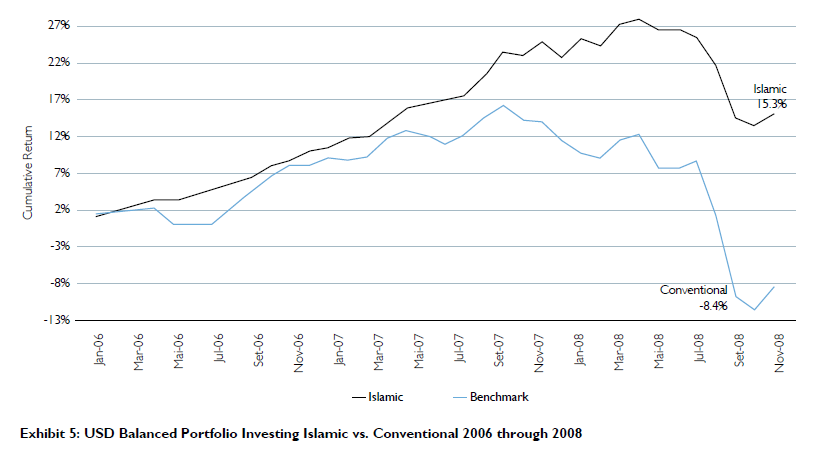

The initial allocation was made using a standard Balanced investment strategy, and benchmarking was quite crude. These early results were stunning. Despite handicaps in both allocation and benchmarking, the initial results gave confidence that further refinement would show sustained outperformance of Islamic allocations. (Exhibit 5)

These initial results showed an Islamic allocation had nearly 24 percentage point positive variance above a conventional benchmark. By any measure and for any asset manager these results are significant to an extraordinary degree. The fact that further enhancing the allocation and benchmarks resulted in continued positive variance (Exhibit 6) confirms the validity of the initial assumptions.

Further, this performance was achieved during remarkable economic times. The time scale from January 2006 through December 2008 included one of the largest run-ups in asset pricing in modern history. Then, as was well documented, markets crashed worldwide and asset valuations tumbled in some cases as much as 90% or more. Asset deflation was not over by the end of 2008, either, despite the upturn in global markets by December of that year.

The initial allocation, therefore, straddled the manic bubble and the equally manic collapse, yet still maintained sizeable outperformance, reflecting a superior style of investing in both strong and weak market conditions.

These initial results were derived from the following al-location as seen in Exhibit 6.12

Further, there was no real effort to properly benchmark the results. The above benchmark is composed of 1) a 50% weighting from the Dow Jones U.S. corporate 5-year investment-grade bond index, 2) a 35% weighting from the S&P 500, and 3) a 15% weighting from the NASDAQ 100.

It was initially thought that these weightings were sufficient for a comparative benchmark simply because the price volatility of the components were guessed to be roughly equal to the volatility experienced by what would have been a more accurate benchmark, if one had been constructed.

Moreover, it was thought at that time the results were so clearly superior that the underlying premise—Islamic asset management could be proven equal or even superior to conventional investing—would survive even more so- phisticated portfolio modelling and benchmarking.

And, they did.

Testing the Islamic allocation Model

For this year’s report new set of portfolio allocation models were formed thus creating an updated global database of Shari’a-compliant assets which were sorted and filtered using the same conventional techniques (plus, of course, adding the Shari’a-compliance filter described in previous works).

Many anomalies appeared during the process of identifying the 830 mutual funds and exchange-traded funds that were discovered. Some were obvious, some not so. The process itself was simple. Our search involved naming any investible security that had both the nomenclature “fund” and “Islamic” on it. One would think this would be straightforward, but it is not always so. For one, hundreds of investment products were created since around 2002 by the dozens of newly created “Islamic” banks in the Arabian Gulf region. A good deal were just very high-risk real estate development funds (e.g., nearly all products from Gulf Finance House), which were categorized as pure private equity. Others were not so obvious.

One well-known bank in the Gulf region, for example, refused to disclose any information at all on their funds—both Shari’a-compliant and conventional—saying such information was given to customers only. This is at direct odds with the industry practice of listing all funds on the Internet and providing regular, transparent disclosure of those funds for interested investors of any kind. For this bank all their Shari’a-compliant funds had to be deleted from the database, as full disclosure and transparency are a requirement of asset management anywhere and all the time.

Many funds were mislabeled, knowingly or not, which caused considerable confusion and presumably caused the same confusion among investors. On closer investigation of one particular sukuk fund, further investigation disclosed the real nature of the fund, again very high-risk real estate speculation that had nothing to do with the commonly referred to concept of sukuk.

As indicated above, the resulting funds that met all professional tests—including track record, assets under management, liquidity, ability to clear and settle across borders, and of course compliance from respected scholars—left us with only 99 funds representing about USD 30 billion in assets under management. This itself is a concern for professional asset managers who wish much larger pools of potential assets to choose from in all asset categories. But the risks associated with these funds were considered, and it was determined that indeed the 99 funds and USD 30 billion in assets met the minimum requirements for assembling Shari’a-compliant portfolios. Much is made about investment risk, in particular risks in investing in funds that are too small or too new. Most of these arguments are acceptable, but at the same time it must be recognized that risk is sometimes immeasurable, or at least difficult to measure. What, for example, is the additional risk of a fund with only USD 90 million of assets under management if a bank’s investment criteria prohibit funds with less than USD 100 million? And, what is the additional risk if one buys a fund with only a 3-year track record versus the often-cited mini- mum 5-year track record? These questions have yet to be answered.