Introduction

The global economic crisis has been an important turning point for the Islamic capital markets the world over. It can be reasonably argued that years between the emergence of Shari’a-compliant finance as a dis- tinct sector (starting in the 1970s) and the onset of the credit crunch in August 2007 marked the initial, albeit rather drawn-out phase of extensive development for Islamic finance. This was a period characterized by the gradual emergence of Shari’a-compliant products in key categories and of rapid growth in the number of Shari’a-compliant financial sector institutions. By the time the crisis hit, Islamic finance had established itself as a large industry with an international footprint and a diverse array of products and services. Even though the growth and convergence potential of the sector is far from exhausted, the initial phase of dynamic expansion and innovation now appears to be largely over. The global crisis has been an important test to the sector and an ultimately valuable reminder of the need to structure products and strategies in a way that makes them resilient in the face of economic uncertainty. The downturn, by creating thorny problems, has also enabled the industry to grow its human capital base in the form of more experts with an understanding of what to do when Islamic financial products run into difficulties.

The impact of the crisis on Islamic finance has been dichotomous. On the one hand, it has become clear that the principles underpinning Islamic finance, which in turn are based on centuries-old tried and tested values, have protected Islamic finance from the excesses that brought the Western financial system to the brink of collapse. The aversion to leverage has been particularly important in the face of a systemic shock triggered in essence by reckless credit expansion. Those market participants that used to criticize Islamic finance, as well as government regulators in countries with sizeable Shari’a-compliant industries, for being too restrictive and conservative, now applaud and seek to emulate them. As people the world over seek to return to traditional values in finance, Islamic finance stands in good stead as an established paradigm whose credibility has been enhanced by its performance.

On the other hand, however, Islamic finance has obviously not been immune to the crisis. The downturn has severely tested pre-crisis assumptions and euphoric attitudes while also underscoring the need to better define and structure Shari’a-compliant products. Having been subjected to this test, the industry now has a much better idea of what works and what does not. But the crisis has also underscored the extreme urgency of broaden- ing the product offering in Islamic capital markets and Shari’a-compliant finance more generally. The Islamic institutions that ran into difficulty typically had excessive exposures to a single asset class, often real estate, in the relative absence of established, Shari’a-compliant alternatives. The clients of Shari’a-compliant institutions were hurt by the limited retail product offering which still makes it difficult for people to build diverse portfolios balanced in terms of risk and return. Companies relying on Islamic finance have struggled due to the general underdevelopment and tensions of Islamic capital markets at a time when banks became reluctant to lend.

Thankfully, the crisis has coincided with important progress in addressing these limitations. The initiatives in the Gulf region have been particularly important, al- though they partly reflect the fact that the GCC had been lagging behind the other main hub of Islamic finance, namely Malaysia, in a number of respects. The most important progress has taken place in the area of debt capital markets where a number of important initiatives are underway with respect to the market in-

frastructure, regulations, and product offerings. Following the pioneering move by NASDAQ Dubai, the Saudi Arabian Stock Exchange Tadawul launched a new secondary board for bonds and sukuk last year and Qatar Exchange is understood to be considering similar plans. The oft-heard criticism of a lack of benchmarks is also being addressed with a number of regional sovereign issuers tapping the market and Qatar leading the way with a deliberate plan to create the framework for a domestic debt capital market through issues of different maturities and structures. But there have been significant government issues – primarily, but not exclusively in the conventional space – also in the rest of the region with the exception of Saudi Arabia which is not planning to tap the market before the national debt to GDP ratio is brought below 10%. However, even in Saudi Arabia, important benchmark issues continue to be made by the partially state-owned SABIC and Saudi Electricity.

Government activism has in turn encouraged others, most notably state-owned companies, to tap the sukuk and markets. In Saudi Arabia, additional expectations are created by the pending implementation of the mortgage law which would create a market for mortgage-backed securities. Partly because of the downturn in the IPO market and restrictions on bank lending, bonds and sukuk are now belatedly gaining popularity as ideal instruments for funding long-term development and infrastructure projects as well as corporate restructuring needs. By doing so, they offer opportunities to buy into the some of the most compelling growth stories in the region. Nonetheless, a great deal of work remains to be done in terms of developing attractive and cost-effective products that can compete with the conventional alternatives.

The growing popularity of sukuk has coincided with an acute recognition of the need to address some of the weaknesses of the still-emerging market. Developments over the past year, triggered in part by efforts by AAOIFI, have led to greater structural and conceptual uniformity of the market. The defaults in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE have boosted transparency and risk management and also resulted in considerable progress in procedures and know-how for dealing with stressful situations. Among other things, some of the regional governments have been forced to provide far greater clarity on the nature of implicit guarantees and investors themselves are likely to be more discriminating, at least for a time.

The beginnings of Islamic capital markets

The emergence of Shari’a-complaint finance was perhaps somewhat paradoxically led by banks, ie credit institutions, first among them Tabung Haji, or Pilgrims Management and Fund Board, established by the Malaysian government in 1962. An Egyptian bank in Mit Ghamr began to invest its funds on a profit-sharing basis in 1963. In 1971, the Mit Ghamr model was embraced by the Nasr Social Bank of Egypt and by 1976, nine Egyptian banks had adopted an explicit no-interest policy.

The first explicitly Islamic financial institution, the Islamic Development Bank (IDB), was established by Organization of Islamic Countries in Jeddah in 1975. The IDB was given an explicit objective of promoting Islamic banking globally and providing assistance for the economic and social development of its member states in accordance with Shari’a principles. The bank collects fees for its financial service offerings while providing profit-sharing-based assistance for various projects. Currently, 56 countries are IDB members.

IDB acted as an important catalyst for the Islamic banking industry with the incorporation of Dubai Islamic Bank in 1975. Other notable Shari’a-compliant institutions that came into existence soon after included Faisal Islamic Bank of Sudan (1977) and the Bahrain Islamic Bank (1979). Pakistan authorized Islamic banking at the state level in 1979

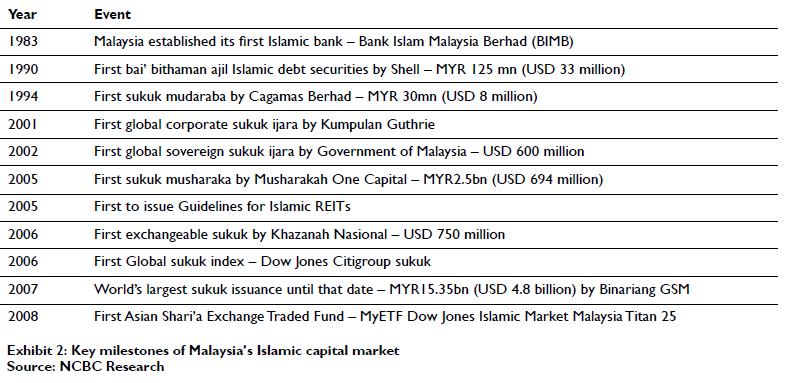

The 1980s saw a steady expansion in the geographic footprint of Islamic financial institutions, as Shari’a-com- pliant banking and financing concepts spread rapidly across Asia. In 1981, Pakistan allowed its conventional banks to offer interest-free counters across branches to mobilize deposits on profit/loss sharing basis. Malaysia, on the other hand, adopted a gradual approach in implementing Islamic principles for its financial system. Malaysia established its first Islamic bank, Bank Islam Malaysia Berhad in 1983. Countries such as Sudan and Iran also started reforming their banking systems to conform to Shari’a principles. However, the major development in Islamic finance was the emergence in 1985 of a dis- tinct insurance concept, takaful or Islamic insurance. The process was initiated by the Council of Organization of Islamic Conference (OIC) that declared takaful as Shari’a-compliant. Nonetheless, the range of products and services remained narrow until the 1980s, with the focus being on deposits and savings activities.

Growing sophistication

By the late 1990’s, the need for distinctive capital market solutions became evident in the face of a palpable economic take-off of majority-Muslim emerging markets such as Malaysia and the Gulf countries. This ultimately led to the introduction of several new innovative products such as sukuk, Islamic equity funds, and various structured products. The first private-sector sukuk issues were launched in Malaysia in the 1990s, but over time, also governments played a key role in sponsoring these developments. The Malaysian government issued the first global sovereign sukuk in 2002 and this encouraged other Muslims countries to follow suit. Increasing deregulation and liberalization of capital markets in the GCC and other Islamic countries, along with the growing demand for innovative financial products, paved the way for the creation of an Islamic capital market infrastructure, complete with Islamic equity indices, asset-backed securities, investment banks and brokers/dealers. In recent years, a growing number of Islamic solutions have emerged for asset management and venture capital services. Product innovation was above all driven by the growing Shari’a-compliant financing needs of corporate and governments but also a pressing need to address the liquidity management problems of Islamic banks.

Islamic equity markets

The Islamic equity market is composed of equities of companies that do not engage in activities that are considered haram (forbidden) in Islam. This excludes ventures involving gambling, pork (food businesses), alcohol (wine and liquor makers), tobacco (cigarette and related product companies), pornography (entertainment and hotel stocks), and arms and ammunition. Similar restrictions pertain to companies whose debt is to a large extent interest-based or those that derive a significant proportion of their net income from interest payments on deposits held in conventional financial institutions. Such entities are excluded even if their main business is otherwise halal (permissible). In addition, equity offerings of conventional financial services institutions (including banks, mortgagers and insurers) and companies with high debt or cash positions are also not considered Shari’a-compliant.

The identification of Shari’a-complaint stocks in turn made possible the creation of Islamic indices. The Islamic equity index was first launched in Malaysia by RHB Unit Trust Management Bhd in May 1996. This was followed by the launch of Dow Jones Islamic Market Index by Dow Jones & Company in February 1999 and the Kuala Lumpur Shari’a Index by Bursa Malaysia in April 1999. In October 1999, the FTSE Group also launched the FTSE Global Islamic Index Series. Major index providers, which include MSCI, S&P, and Dow Jones, have in recent years launched a large number of similar Islamic indices.

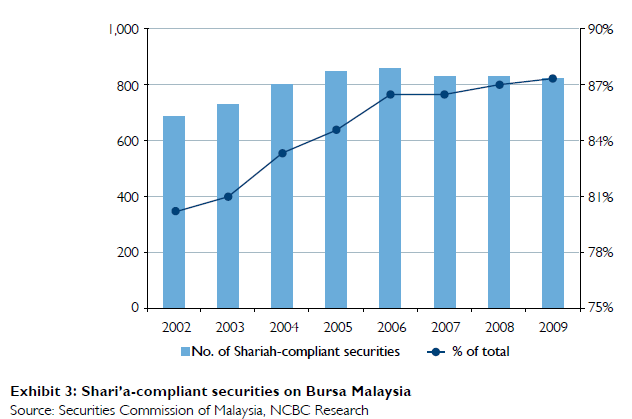

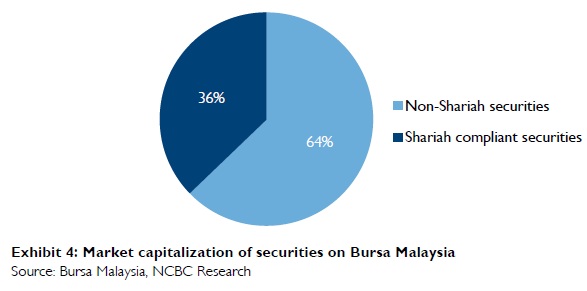

The growth of the Islamic equities market can be gauged from the progress made in Malaysia. The number of Shari’a-compliant equities listed on Bursa Malaysia has increased steadily from 787 in 2004 to 847 in May 2010. In fact, Shari’a-complaint securities accounted for 64% of the total market cap of Bursa Malaysia in 2009, compared with 58% in 2003.

Sukuk Markets

Sukuk are generally thought of as the Shari’a-compliant alternative to bonds. Indeed, much of the initial evolution of the market arguable involved the financial reengineering of bonds with a view to giving them a Shari’a-compliant veneer. Even though the stricter interpretation of sukuk essentially views them as analogous to preference shares, the references to bonds have persisted due to the use of sukuk in raising capital for a finite period, until recently typically up to five years and virtually never more than ten. However, the past year has seen efforts to widen the range of tenors through the issuance of seven-year, as well as short-term (less than a year) sukuk.

Efforts have been underway for a number of years to give sukuk a more distinctive Islamic identity, in part by basing them on the principle of risk-sharing. Recent ef-forts by AAOIFI have been particularly important in this regard, both in terms of fueling greater standardization and by seeking to ensure that sukuk have a concrete underlying asset. Indeed, AAOIFI found that the vast majority of the pre-2008 sukuk issuance was in violation of its new rules. Under the proposed paradigm, the issuer of a sukuk provides a financial certificate to investors who are given proportionate ownership of the underlying asset for a pre-defined period. Moreover, unlike conventional bonds, which provide a fixed interest to bond holders, the sukuk issuer agrees to provide a return to investors in the form of payments that are linked to cash flows generated from the underlying asset for which capital is mobilized. This model should, under the circumstances, not provide any guarantees of principal repayment at the end of the period as the value of the asset can vary.

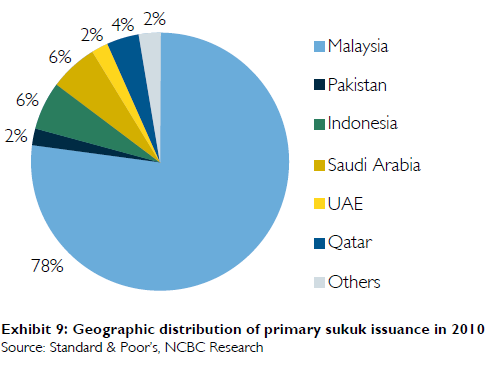

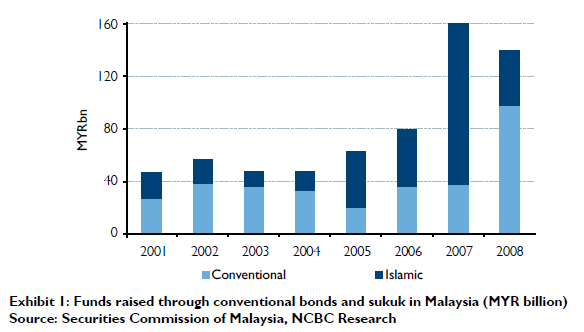

The first sukuk ever was issued by Shell MDS in 1990 for MYR 125 million (USD 33 million). Since then, the progress of the market depended heavily on efforts of the Malaysian government that had made the world’s first sovereign USD 600 million sukuk issue in 2002. Malaysia’s Cagamas MBS has issued USD 540 million worth residential mortgage-backed securities. Malaysia has also seen issuance by corporates, including notably a pioneering USD 2.86 billion issue by the PLUS highway concessionaire in 2006. The government’s investment arm, Khazanah Nasional, issued the first exchangeable sukuk the same year.

Following the Malaysian precedent, also other Islamic countries entered the sovereign sukuk market. Bahrain led the way with a USD 100 million issue in 2001. Qatar issued a global sukuk of USD 700 million in 2003, and Pakistan came out with USD 600 million issue in 2005. In the Gulf, Bahrain remains the most active sukuk market. The country regularly issues short-term sukuk for liquid- ity management. In 2002, Islamic Liquidity Management Centre was established in Bahrain in order to boost sukuk issuances. Qatar has recently intensified its efforts to develop the national debt capital markets and this year issued domestic sukuk, as well as bonds, partly for the purposes of liquidity management in the banking sector.

The world’s first global corporate sukuk issuance for USD 150 million was made by Kumpulan Guthrie, a Malaysia-based company, in 2001. Since then, sukuk have not only grown in size but in product sophistication and structure. Bai bithaman ajil was initially the most popular form, accounting for 77% of total issues in 2001. However, efforts aimed at standardization, notably by AAOIFI, have now effectively made ijara the dominant structure, albeit in a market that has seen historically subdued issuance levels.

Global sukuk issuance grew steadily from USD 5.8 billion in 2003 to USD 33 billion in 2007. Even as the onset of the financial crisis and the debate on Shari’a- compliance standards temporarily reversed the positive progress, restrictions on bank credit and depressed stock markets have stimulated interest in bonds and sukuk. Moreover, sukuk have continued to benefit from high yields as well as perceptions of them as a ‘less risky’ investment proposition compared with conventional bonds, in part because they are typically backed by physical collateral. Indeed, efforts to ensure that this is the case have been among the focal points of recent efforts to standardize the sector. Moreover, the huge public and private investments undertaken in emerging economies, particularly in infrastructure, have boosted funding requirements in areas essential for economic development. Leading Middle Eastern sukuk issuers include companies such as the petrochemicals giant SABIC and the Saudi Electricity Company, as well as a growing number of real estate developers.

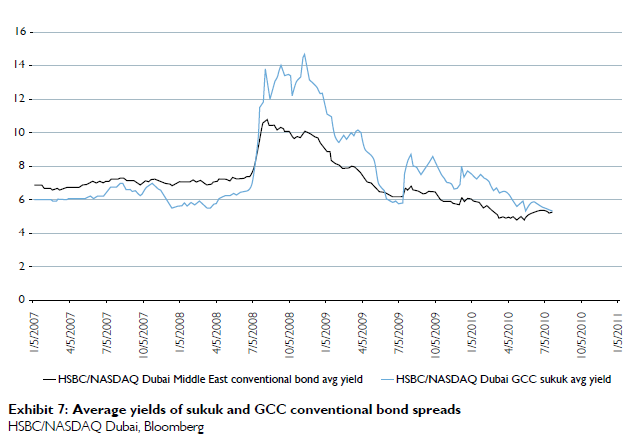

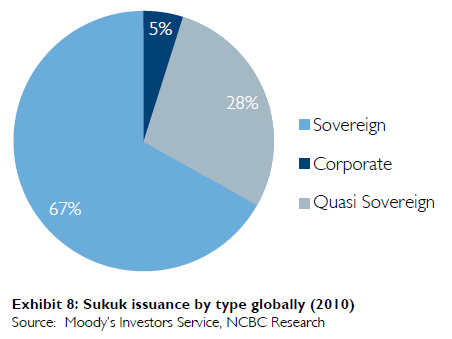

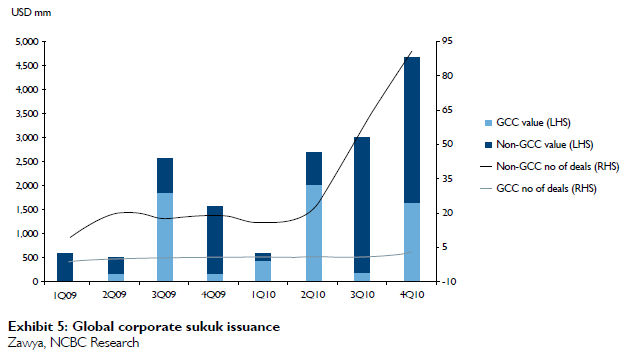

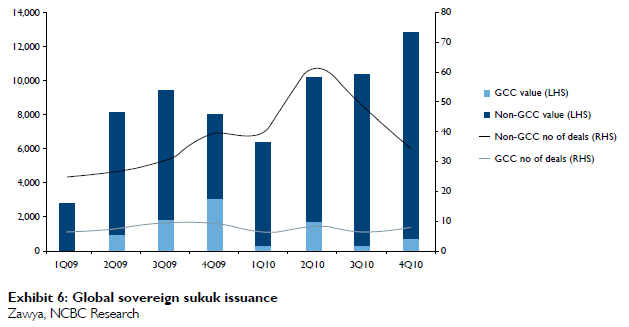

In spite of the promising potential and market drivers, the progress made in recent years was abruptly reversed in 2008 when total global sukuk issuances declined to USD 15 billion, as the broader debt capital markets dried up globally. In terms of types of sukuk issuances, corporate sukuk nonetheless continued to narrowly overshadow sovereigns and accounted for 56% of all sukuk issued in 2008. 2009 and 2010 have been marked by a cautious but a fairly consistent recovery. In 2009, sukuk issuances rose to USD 27.1 billion, which was followed by a further rebound to USD 38.0 billion in 2010. Nonetheless, the upturn has been an uneven and somewhat anxious one, due to the prominence, especially in the Gulf, of market stress linked to high-profile sukuk restructurings. These have in some instances necessitated government intervention and regulatory innovation. . Concerns over the restructuring terms have tended to make for greater market tension in the sukuk space as compared to conventional bonds (Exhibit 7). At the same time, the reliance of the market on a limited number of large issues by sovereigns and blue-chip names has translated into considerable quarterly variation in issuance volumes (Exhibits 5 and 6). Periods of market stress – some of them linked to the European sovereign debt crisis – have prompted many issuers to delay their plans. The market was also hit by the sharp cycle in real estate as well as, to an extent, in finance. Many of the property and financial companies that had driven sukuk issuance before the crisis largely withdrew from market. In the GCC, financial sector sukuk issuance declined from 17% in 2008 to 6.7% in 2009 while the share of real estate plummeted to 3.6%. The impact of these changes was particularly linked to the troubles of the UAE economy and especially Dubai. By contrast, corporate issuance has been robust in the dynamic Malaysian and Indonesian markets where new activity has been driven by a robust economic rebound.

As corporates retreated, sovereign issuance has once again become the backbone of the GCC sukuk markets. Sovereigns made up 91% of GCC sukuk issuance in 2009, up from 65% in 2008. 2010, by contrast, saw something of a revival in the corporate space, although sovereign programs also continued apace, most notably in Bahrain and Qatar. Also the Indonesian, Gambian, and Brunei governments tapped the Shari’a-compliant markets. Although corporate issuance has by no means normalized, there have been a number of landmark issues, not least the Saudi real estate developer, Dar al Arkan’s USD 450 billion issue in early 2010, which was the first Saudi 144a corporate issue open to US investors. Saudi Electricity Company broke new ground with a SAR 7 billion seven-year issue, having previously limited the tenors to five years. In general, the sluggish nature of the GCC sukuk market seems to reflect at least in part the residual concerns about sukuk structures and the potential risks pertaining to default-type situations. Under the circumstances, the improvement seen in the pricing of GCC sukuks has been clearly slower than that observed in the conventional market. The end of 2010 has seen tentative signs of optimism in the sukuk market. The Dubai World deal has boosted confidence, while the European situation gained a temporary respite from the Greek bail-out and the establishment of broader bail-out mechanisms. While the situation is showing signs of deteriorating again, GCC and South-East Asian sukuk issues are internationally active in terms of their fundamentals and prospects. There are signs that the region will reap at least some of the benefits offered by the latest wave of US quantitative easing as US investors seek yield outside their home markets. Even as the GCC sukuk markets have languished in relative terms, there has been increasingly strong momentum in South-East Asia, some of it involving Malaysian Ringgit-denominated issues by GCC entities. However, the positive momentum, especially in the wake of the Dubai World deal, is expected to lead to the re-activation of some of the GCC pipeline, even if political unrest in North Africa may temporarily curb the momentum. The regional refinancing needs are growing and the range of sukuk products widening in terms of tenors. Moreover, there is a structural imperative for catch-up in the GCC. During the crisis, Malaysia has consolidated its status as a sukuk hub in spite of the significantly smaller size of its economy – only about a fifth of the GCC (Exhibit 9). Quasi-sovereign infrastructure spending has been a critically important dimension of sukuk issuance and highlights the potential in this regard also in the GCC. Merely matching, the relative size of the Malaysian sukuk markets would offer considerable upside potential for the GCC.

The near-to-medium-term outlook for the global sukuk markets is generally benign, both thanks to a projected cyclical recovery in many of the key issuer markets and a number of powerful structural forces. While the cyclical recovery should reduce the need for government sukuk issuance, the pace of the upturn in bank lending may prove cautious. The current pipeline for bonds and sukuk in the GCC and South East Asia alike is sizeable and many issuers are likely to proceed with their plans in conditions of diminished market stress, not least be- cause of the demonstrated benefits of developing new sources of capital. In particular, corporates are likely to be able to reliably and cost-effectively fund their long-term needs through bonds and sukuk. Bank credit has been repeatedly shown to be an inadequate means of long-term capital raising, both due to the inevitable tenor mismatches and also the cyclical challenge of elevated risk aversion, as demonstrated during this crisis. The most compelling case for long-term sukuk finance comes, as noted, from the infrastructure development plans of emerging markets, although sustained success in this regard will necessitate structural innovation and longer tenors. In the GCC alone, infrastructure investment needs are estimated at possibly USD 120 billion over the next decade. The regional development plans envisaged total spending amounting to hundreds of billions of dollars in the next five years – USD 385 billion in Saudi Arabia, USD 129 billion in Kuwait, etc. The aggregate value of ongoing construction projects is in excess of USD 700 billion. A number of challenges persist in terms of developing acceptable sukuk solutions and the secondary markets needed for a larger, more liquid market. However, the developments of the past several years give grounds to cautious optimism in this regard.