Three years ago protestors stood in Tahrir Square convinced they were entering a new and freer era in Egypt. Optimism has quickly turned to pessimism and concern. Today, déjà vu has crept in with the soon to be inauguration of a military leader and a crackdown on an Islamist group. What could this mean for the country in the next few years? In this article we explore the situation in Egypt and ponder whether things could turn worse, a consequence that could have sizable ramifications for the region and for the wider economy.

A new normal in Egypt, much like the old normal but harsher

Since the ouster of Morsi last summer, Egypt has been a bit stranger than normal as the deep state and army have solidified their control over the country to a level far above that of Mubarak. The Muslim Brotherhood has not only been removed from power but deemed a terrorist group and ostracised from society. To serve as a further humiliation, the Minya Criminal Court sentenced 529 in March this year to face the death penalty for the murder of a police officer and attempted killing of two others in a police station following protests last August.

Given that the verdict was delivered in only two sessions and only 142 of those sentenced to death were actually under custody (53 were in court), it is unlikely that these death sentences will be upheld. Nevertheless, irrespective of the legal irregularities which undermine the judgment, this was a clear sign that the state organs are going to adopt a strong and harsh stance against the Brotherhood.

Arab Spring lesson: if you crack down, crack down hard

With protests continuing despite the illegality of the Muslim Brotherhood and the rising levels of terrorist violence led by Ansar Jerusalem, the government and army have clearly decided to take a hard line against any form of protest in order to try to nip it in the bud. This posture has proved remarkably efficient over history in putting down insurrections, with the fault lines it opens up dependent on the willingness of the broader populace to accept such extreme action. In the case of Egypt, the anti-Muslim Brotherhood sentiment from those who felt they were a threat to their way of life remains high so we can expect continued aggressive policing with minimal disapproval.

However, the outlet of frustration is likely to move further underground gradually becoming more extreme, which is why we must consider the development of armed insurrection and how it may pan out in Egypt. The conflict in Algeria in the early 90s offers an uncomfortable precedent given that civil war was a consequence.

Will past Algeria be future Egypt?

Following the oil price collapse in the 1980s, President Chadli of Algeria found his support being eroded dramatically with October 1988 riots representing a culmination of frustrations against the beleaguered leader. So, in a desperate attempt to garner support, President Chadli called for a referendum on the constitution in February 1989 to move away from socialism towards democracy. He hoped that in ensuing elections the support for the FIS (Front Islamique de Salut, aka Islamic Salvation Front) would help balance out the democratic RCD (Rassemblement pour la Culture et la Démocratie, aka Rally for Culture and Democracy) party, allowing his own socialist FLN (Front de Libération Nationale) to win easily.

This was a huge miscalculation. The highly organised FIS leveraged its dual leadership structure, with Abassai Madani reaching out to the middle class and Ali Benhadj appealing to the working classes, particularly the young urban poor. They won a series of local and municipal elections in June 1990 cementing their power and influence particularly amongst the urban youth that looked towards enforcing Islamic law. Aghast, the FLN adjusted the electoral constituencies as a result, leading to the FIS calling for a general strike in June 1991 and Ali Belhadj calling for the FIS to take up arms if the FLN tried to stop them.

The leadership of the FIS was duly thrown into jail, but even though they lost a million votes, the FIS led by the new leader Hachani, still won the first round of postponed elections in 1992 with 66% of the vote, a level that would have allowed them to change the constitution. However, the army stepped in to “defend democracy”, dissolving the FIS and arresting 40,000 people.

The new President Boudiaf, a prior hero who returned from a 27-year exile in February 1992 to try to stabilise matters and clear up corruption, was subsequently assassinated by his own bodyguard in June 1992, making the situation even messier. The FIS started to fracture and extremist splinters coalesced, with the first major group being the GIA (Armed Islamic Group), led by Abdel-Haq Layada, a former car mechanic, who actively recruited veterans of the Afghan jihad.

Much like today’s Boko Haram, the basic principle of the GIA was that the West was in terminal moral decline and many Algerians had become overly westernised, entering a state known as “jahiliyyah”, a kind of aggressive ignorance, which took them outside the fold of Islam. Thus the call was not for any democratic re-establishment, but for the full imposition of a very restrictive view of Islam, with significant recruitment coming from individuals marginalised by Algerian society.

The GIA constantly broadened its range of targets, including foreigners in 1994 and other jihadists in 1995, eventually leading them to implode, but not before tens of thousands of Algerians and foreigners had died. Indeed, this is a hallmark of fundamentalist jihad – you tend to have a core of “true believers”, whose rejection of most of humanity causes them to become exceptionally paranoid. The majority of neophytes tend to be those that piggyback on their momentum. This is until they start to turn in on themselves or they receive significant external support by others using them for their own means, something that we have seen recently with Al Shabaab in Somalia.

Looking back at Egyptian jihad

In considering how current Egyptian groups have formed and how lessons from Algeria may feed in, it is also instructive to look at the Egyptian jihadist groups that popped up in the last few years.

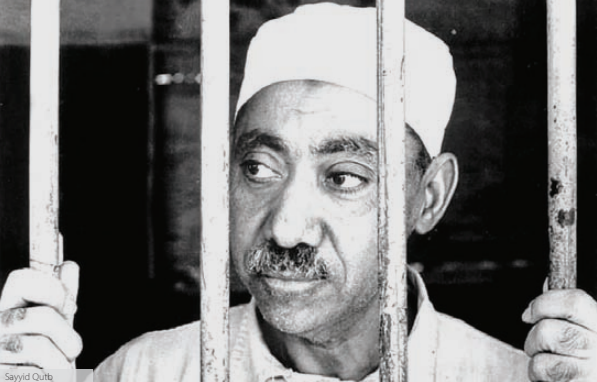

The origins of modern jihadist groups can be traced back to one of the early leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood, Sayyid Qutb, one of the key proponents of the concept of jahilliyah. Qutb’s relationship with Nasser had previously been congenial particularly after the coup of 1952, but conviviality failed to last after Qutb turned down a variety of positions in the government. It led to Qutb’s incarceration in 1954 where he was accused with other Muslim Brotherhood members of attempting to assassinate Nasser. As Nasser cracked down on the Muslim Brotherhood that he had previously seemed so close to (using his Tahrir (Freedom) organisation, history really does rhyme), extremist elements came out focusing on Qutb’s work written during his imprisonment especially those in his seminal work “Milestones”.

The spread of anti-secular and anti-Western principles of Qutbism accelerated in the late 1980s (Qutb was hung in 1966), particularly thanks to a huge surge of funding and organisational support given to Al Qaeda during the Soviet War in Afghanistan. Splinters of the Muslim Brotherhood periodically gave up on peaceful community organisation after being imprisoned and suppressed, resorting to terror attacks, notably assassinating Anwar Sadat in 1981.

Jihadist attacks peaked in the late 1990s with the Luxor massacre of November 1997. 62 people were killed by gunmen from a splinter group of al-Gamaa al-Islamiyyah, purportedly under the planning and influence of Ayman al-Zawahiri. The attack attempted to undermine the Egyptian economy and puncture the nonviolence initiative of July of that year when the main group had renounced violence. Their aims were thwarted as the attack destroyed all public support for jihadist groups in Egypt, leading to mass protests against terror groups that had previously relied on local knowledge and support for their organisations.

The Iraq war in 2003 led to another surge of support for jihadist movements, with the simultaneous bombings in Taba and Nuweiba in October 2004 leading to an indiscriminate crackdown by the security forces. They arrested over 3,000 people and employed very harsh, direct tactics. The crackdown only served to build sympathy and support for these groups once more, not from an ideological vantage, but rather as a means to vent anti-government frustrations.

Some jihadists gave up their weapons to do social work, others became post-jihadists in jail and tried to de-radicalise others. Most of those who did not give up their guns moved away from targeting the booming tourism industry to a more broadly appealing target, Israel, led by a group known as Majlis Shura al-Mujahidin fi Aknaf Bayt al-Maqdis, commonly known as Ansar Jerusalem. The Arish- Ashkelon gas pipeline is a favoured target.

Understanding modern Egyptian terror and how it may evolve

Ansar Jerusalem has made quite a splash in Egypt since Morsi’s ouster, turning from a fringe group attacking primarily Israeli targets to one conducting hundreds of operations in the Sinai and beyond, including the September 5th assassination attempt in Nasr City on Interior Minister! Mohammed Ibrahim and the recent terror attack in Taba. The group is part of Al Qaeda’s loose transnational jihad network but operates largely independently from them. They like to talk through their attacks, with videos and press releases outlining their motivations, modus operandi and likely direction.

While the Egyptian government has indicated that this group is part of the Muslim, with some saying it is directly funded by former leader Khairat al-Shater, most of the videos of suicide bombers indicate disdain both for the principles of the Muslim Brotherhood and the organisation itself. This is not the popular view in Egypt, with some polls indicating a third of Egyptians believe the Brotherhood was responsible for the Mansoura bombing despite Ansar Jersualem taking responsibility (only 6% believed they did it).

“ While the government’s tactics for dealing with the opposition are likely to cement their position short-term, the instability in the social fabric of Egypt is likely to increase over the next few years dramatically.”

The membership of Ansar Jerusalem has gradually broadened as well, with membership not only from the Sinai bedouins, but from educated middle-class Egyptians and fighters returning from the Syrian war (which was supported by the Muslim Brotherhood).

The release of hundreds of Islamist convicts between the ouster of Mubarak and Morsi taking power also strengthened the ranks of Ansar Jerusalem, which currently seems to be around 2,000 strong (versus 500,000 or so Muslim Brotherhood members). Many of those released were innocent, but some were unreformed jihadists, with even the al-Zomor brothers, convicted of Sadat’s assassination, released.

While the criticism of the Muslim Brotherhood is pointed in many places, with, for example, the Nasr city bomber Waleed Badr saying that they erred in pursuing “this farce called democratic Islam” and saying they were aping the west (the jahiliyyah refrain), most of the ire of Ansar Jerusalem is reserved for the army, particularly given its apparent acceleration in normalising relations with Israel at the expense of the Palestinians.

Originally the group warned Egyptians to stay away from security HQs as they were “legitimate” targets, but now they are expanding to tourist sites, as can be seen by the Taba attack, in an attempt to cause economic instability. It is notable however that the rhetoric and basis of the attacks are distinct from the Algerian Civil War and the

GIA as while the range of “acceptable” targets is widening, the level of takfir – declaring others as outside of Islam – is not, with the targets being primarily non-Muslim even in the case of the Taba attack.

If the government does carry out the death sentences and continues to crack down hard, groups such as Ansar Jerusalem are highly likely to swell and tourist attacks may accelerate. However, the primary target is the army in the case of Egyptian jihadists and, as with many jihadist groups, the goal is political as opposed to ideological, which may give it more staying power than other groups that have flamed out.

Additionally, the primary focus is unlikely to be the tourist industry as it remains in the doldrums and the government’s focus, with Gulf aid, is on infrastructure projects to fill the gap. The relatively open border with heavy weapon-rich Libya to the South affords plenty of opportunities for more balanced warfare with security forces (as evidenced by the recent shooting down of a military helicopter). This will be more successful in causing a disproportionate response bringing more recruits (a tactic employed by jihadists in Syria) and weaken the overall economy (the key modus operandi of Al Qaeda).

What does this all mean?

The reconciliation and gradual reintegration of the Muslim Brotherhood is probably at least 5-10 years away. In the meantime, the Egyptian economy is likely to get back on its feet in the next year or two provided Gulf money continues to come in and while the government’s tactics for dealing with the opposition are likely to cement their position short-term, the instability in the social fabric of Egypt is likely to increase over the next few years dramatically.

ISFIRE Comment

Mt Ghamr in Egypt is constantly offered in the annals of contemporary Islamic finance as a starting point for the industry. Since then, Egypt has at best flirted with the idea of Islamic finance although during the Morsi era there was a definite interest. The turmoil in Egypt is likely to set any kind of meaningful development back, and perhaps a greater concern is the increasing violence that is occurring in the region and its impact on the economy and the people. Syria has been caught by an intractable and grisly war which shows no signs of abating. In fact, the war

is seeping out into neighbouring countries such as Lebanon and Turkey, and hostilities in the region have resulted in broken relationships between countries in the GCC, primarily Saudi Arabia and Qatar. A disunited GCC will lead to a period of instability and uncertainty in the international markets especially as countries such as the aforementioned are playing a greater role in the global economy.

At the root of these fractures is a conflict between Islamist and secular politics. Harmonisation between the two has been an ongoing headache since the fall of the Ottoman Empire in 1924, and no single party has come close to offering an acceptable compromise. Islamic finance, in many respects, has managed to harmonise Islamic laws with secular principles making it a bridge builder between two often conflicting cultures. But its growth can only come with political and civil support. Being swept away in national politics as groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood have done has created a tinderbox in the region and formed conceptual associations between anything Islamic and violence. Islamic finance can fall into this unfortunate trap, which will upend its own global growth. Thus, the industry has to guard itself against a potential backlash, especially in the West, and counter any negative associations. Promotion, advocacy and marketing are important to delink a relationship with political Islam. Indeed, the genesis of Islamic finance is in political Islam but its branches need not be. Relatively more peaceful countries

such as Malaysia and Indonesia can counterbalance the association with anything Islamic to violence. Strengthening their Islamic finance industries has an advocacy effect and so remaining niche and targeting a low percentage of the population will not give the industry the positive profile it deserves. One could argue that we are overstating the metastasis effects of Islamist violence on anything Islamic. Yet we have seen the escalation of suspicion particularly after 9/11. Hence, responsibility on Islamic finance to provide an adequate counterbalance to this anxiety is necessary given the escalation of violence in Muslim countries