After the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) almost a decade ago, many extraordinary transformations have taken place in the global financial system. A novel coronavirus, referred to as COVID-19 pandemic, is the new “black swan” in town. Both the speed and magnitude of this pandemic spread engulfing the whole world has been greater than the GFC.

It is not discriminating between borders, race, ranks, and faiths. From “flattening the curve” to “herd immunity” and “social distancing” to “prudent distancing”, everyone is offering suggestions. One of the many worrying issues around COVID-19 is the spread of pseudoscience, recommending everything from giving up ice cream to drinking bleach, and being caught up in the hysteria and the continuous stream of bad news.

I have never felt more dispirited while writing than the present case. Fear of the unknown remains dominant in our mind as the menace of the unprecedented economic and human crisis of this proportion unfolds. This pandemic is not only a threat to the global financial system bringing dramatic economic effect bigger than the GFC but also underlies long-lasting psychological implications.

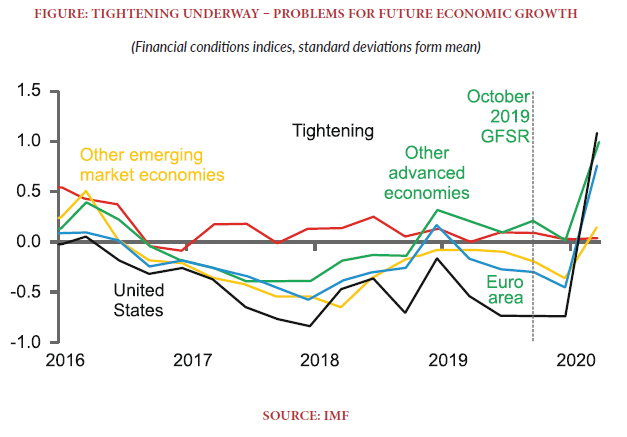

Who would have thought two quarters ago about this pandemic, which is slowing down everything? There are challenging times ahead for countries and financial institutions as financial conditions are tightening (see Figure below). Global financial markets are crashing, airlines are grounded due to cancellation of thousands of flights and countries imposing a ban on travel. Crude oil prices have dropped to the lowest in 18 years. Sharp increase of uncertainty in financial markets worldwide has widened the credit spreads broadly across markets. Currencies have been hit hard against the USD. Significant policy rates cut and open-ended quantitative easing have resulted in global bonds yield declining. Business confidence is falling off a cliff as cross-border trade has been disturbed that provides critical streams of foreign exchange. All of these conditions bring negative implications for businesses which will ultimately impact the financial sector as well as the fragile gig-economy.

The question is: are we headed for recession? The IMF Managing Director, Ms Kristalina Georgieva confirmed during the Opening Remarks at a Press Briefing on March 27, 2020, that “we have entered a recession – as bad as or worse than in 2009”. One can certainly concur with her that “a key concern about the long-lasting impact of the sudden stop of the world economy is the risk of a wave of bankruptcies and layoffs that not only can undermine recovery but can also erode the fabric of our societies”. While the G20 have reported fiscal measures totalling some USD5 trillion or over 6% of global GDP, the question remains: is it enough?

Financial sector, including Islamic finance, is certainly going to be impacted because of the above conditions. In this context, I tend to address the following key questions in this modest piece:

- What is the potential impact on Islamic banks (IBs)?

- How IBs can measure the impact with stress testing?

- How to navigate through this tough time?

- What should be the role of various stakeholders such as regulators and standard-setting bodies for Islamic finance?

“This pandemic is not only a threat to the global financial system bringing dramatic economic effect bigger than the GFC but also underlies long-lasting psychological implications.”

POTENTIAL IMPACT AND IMPLICATIONS FOR ISLAMIC BANKS

The COVID-19 brings a range of potential implications for all types of financial institutions. Being a part of global finance, Islamic finance is no exception as it continues to operate in a similar economic and financial environment. It brings various credit, market, liquidity and operational risks implications proportionate to the size of an Islamic bank, complexity and nature of the dominant portfolio (e.g., real estate, financing-driven, financial investment) and the economy in which it operates.

Let us briefly look at what kind of implications the COVID-19 brings to Islamic banks through a balance sheet approach.

First, the significant decline in domestic and global economic activity brings huge business disruptions. This brings an important implication for sovereign central banks when their rating is downgraded due to the ongoing domestic and global economic outlook, taking into account both monetary and fiscal measures, and their likelihood to honour their debt obligations. This indicates impacts of rating migrations (downward; e.g. AAA to AA) of counterparties (banks, corporates, SMEs, and PSEs) under the standardised approach, which ultimately has an impact on the funding costs as well as Risk- Weighted Assets (RWAs) in capital adequacy.

Second, when central banks are relaxing the policy rate to boost the sluggish economy, the return on investment for placement with the central bank as well as lending to government by banks will attract low investment return. In such a situation, the new financing will also attract low return, and existing financing will be affected by the non-payments due to closure of businesses and people being unemployed for a certain period. Thus, bringing non-performing financing (NPF) high and depleting the provisions. The NPF has implications for expected credit losses (ECL), write-off, and liquidity. This will bring a drag on the profitability of IBs, which will consequently affect the retained earnings, and capital buffer subsequently.

Third, as global financial markets crash – especially, when in developed markets investors sell-off and in emerging markets when investors pull out billions of USD investment – there is an impact to local stock exchanges, bringing negative consequences to financial investment

and Shari’a-compliant instruments. Both yields and value of an investment will go down significantly and will have an influence on the investment income of IBs. Furthermore, real estate investment will be having a downturn and a correction in market valuations due to a decline in demand and relocations.

Lastly, the value of foreign liabilities (FX) surges sharply due to the depreciation of the local currency. The FX market has shown significant volatility. On the other hand, the structural investments by the IBs in their subsidiaries and affiliates can also bring negative implications due to the disruption of business domestically and abroad. Last year, IFSB Islamic Financial Services Industry Report also pointed out the prolonged depreciation of several emerging markets’ currencies from 2017 towards Q3- 2018, which led to a decline in the dollar value of assets.

MEASURING THE IMPACT AND IMPLICATIONS – STRESS TESTING AND REVERSE STRESS TESTING

Now let me address how the impact can be measured. Similar to the GFC, the COVID-19 pandemic has put significant emphasis on the role of stress testing within risk management. Stress testing should form an integral part of the overall governance of the IBs. The ultimate responsibility for the overall stress testing programme is with the board of directors (BOD).

Just like medical unpreparedness has been exposed by this pandemic, similarly, banks will be exposed by not having in place a pandemic scenario that is “low-frequency – high-impact event” which may not be reflected in historical data” or “fat tails event” in their stress testing. Such an event can have catastrophic consequences.

Two quarters ago, the above scenario may not be envisaged by the risk management team and given due consideration due to its plausibility, but now this is a reality.

IBs should include in their stress testing not only the worst-case scenarios but it should also be complemented with reverse stress testing (i.e. striking off a whole business line and estimating whether the IBs can survive). The macro model should not only capture significant drop in macroeconomic variables such as GDP due to significant drop-in business activities in various economic sectors causing unemployment, among others, but also should include spillover effect through trade, tourism, travelling, hospitability, etc. In particular, IBs must pursue a more thorough analysis of risk transmission and contagion mechanisms (including “ripple and reinforcing effects” from a primary stress scenario extending to other markets or products) and also reflect better risk correlations which may vary in stressed conditions.

“A key concern about the long-lasting impact of the sudden stop of the world economy is the risk of a wave of bankruptcies and layoffs that not only can undermine recovery but can also erode the fabric of our societies.”

Severity is to be understood in the light of the specific vulnerabilities of the respective IBs, which might not be equal to the perspective of the total economy. A simple country- or region-specific macroeconomic stress scenario may be less relevant to some IBs’ risk profile than others – for example, if they have a specific industry exposure which is countercyclical, or if their risks are primarily international and less impacted by national scenarios. Deployment of stress testing should be proportionate to the IBs’ size of balance sheets and the extent of their interconnectedness.

A reverse stress test induces an IB to consider scenarios beyond its normal business settings and highlights potential events with contagion and systemic implications. Therefore, reverse stress testing starts from a known stress test outcome (such as breaching regulatory capital ratios, or a liquidity crisis) and then asking what events could lead to such an outcome for the IB. As such, reverse stress testing complements in an important way the existing stress testing framework. It requires an IB to assess scenarios and circumstances that would put its survival in jeopardy, thereby identifying potential IB-wide business vulnerabilities.

Other than conducting reverse stress testing, IBs should include the following key factors in their stress testing exercise (for details, see IFSB-13):

- Significant decline in domestic economic activity;

- Significant deterioration of anchor macroeconomic variables (e.g., oil) or sectors (e.g., tourism, real estate, recreation, etc.);

- Impacts of rating migrations (i.e., historical default experience of IBs of counterparties within specific rating classes (AAA, AA, A, etc.) of different counterparties (retail, corporate or sovereign) under the standardised approach and its impacts on RWA in capital adequacy;

- Adverse shifts in the distribution of default probabilities and recovery rates;

- Policy for determining and allocating provisions for doubtful debts;

- The forced defaults (due to cash flow shortages) and planned defaults (higher probability of default by counterparties and loss given default);

- Fluctuations in values in tradable, or marketable, assets (including Sukūk);

- Equities (stocks) (including those in liquid and/or non-liquid markets);

- FX fluctuations and volatility arising from general foreign exchange spot rate changes in cross-border transactions;

- Severe constraints in accessing secured and unsecured Shari’a-compliant funding;

- The ability to transfer liquidity across entities, sectors and borders taking into account legal, regulatory, operational, and time zone restrictions and constraints; and

- Liquidity reserves and regulatory required ratios (such as LCR and NSFR).

NAVIGATING THESE CHALLENGING TIMES – THE ROLE OF VARIOUS STAKEHOLDERS

As per the IFSB PISIFIs latest data, we should bear in mind that Islamic finance is facing these challenges from a position of overall strength. However, this should not stop IBs taking into account the above stress testing to ensure their continuity and sustainability. In particular, it is worth noting that the global Islamic banking industry experienced only 0.9% growth in assets to close at approximately USD1.57 trillion (2Q17: USD1.56 trillion) and thus its share in the overall IFSI has slightly contracted to 71.7% (2017: 76%) (IFSB IFSI Stability Report, 2018). This monotonous growth over the period was attributed mainly to the depreciation of local currencies in terms of the USD, especially in some emerging economies with a significant Islamic banking presence. With this trend and the ongoing deterioration in global economic and financial conditions, growth in the Islamic banking sector is certainly being threatened by the devastating effects of COVID-19 outbreak.

ROLE OF ISLAMIC BANKS

We should bear in mind that unless one is unable, it is very reprehensible delaying to pay one’s debts. Taking into account the above implications for the IBs arising out of their balance sheet; firstly, the IBs should provide relief to the customers (individuals, companies, SMEs) which are adversely affected by the COVID-19 in line with their respective central bank instructions.

In such a difficult time, we should remember that Allah SWT, in the Holy Quran in Surah Al- Baqara, instructs creditors to be patient with the debtors who are having a hard-financial time. Grant them time until it is easy for them to repay: “And if someone is in hardship, then [let there be] postponement until [a time of] ease. But if you give [from your right as] charity, then it is better for you, if you only knew.” (2: 280).

In terms of classification and provisioning standards (e.g. rescheduling, refinancing or reclassification), IBs should bear in mind that Shari’a rules and principles do not allow to refinance debts based on renegotiated higher markup rates; however, debt rescheduling or restructuring arrangements (without an increase in the amount of the debt) are allowed.

“And if someone is in hardship, then [let there be] postponement until [a time of] ease. But if you give [from your right as] charity, then it is better for you, if you only knew.” (2: 280)

Secondly, the IBs should continue paying compensation in appreciation of the banks’ employees for their work during the holidays or when working remotely.

Thirdly, to fulfil the Maqasid al-Shari’a, IBs should divert all of their CSR activities and budget in a Fund established by the government or by other organisation(s) fighting for the COVID-19. Subject to the respective SSB’s approval, the IBs can pay the Zakat to this Fund for the COVID-19.

CENTRAL BANKS – REGULATORS’ RESPONSE AND NEEDED MEASURES TO SUPPORT IBS

Both the governments and central banks have come forward in Islamic finance jurisdictions to provide monetary and fiscal stimulus packages and instructions respectively. These measures have provided breathing space to the banking sector and the overall economy during the lockdown period.

It is commendable how various central banks (e.g. BNM, CBK, CBUAE, QCB, SBP, and SAMA) have announced several regulatory, supervisory and administrative measures in support of efforts by banking institutions to assist individuals, small and medium-sized enterprises and companies to manage the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

These measures include, among others, moratorium and/or restructuring of financing facilities for a certain period, special discounts to essential sectors for exports, liquidity facilities to banks via various tools under open market operations, procedures to ensure swift and efficient operations, uninterrupted access to financial services to the general public, prioritising working remotely within the banks’ business continuity plan, and disinfection of vaults and currency notes.

Other than deferring the implementation of the Basel III and its equivalent IFSB regulatory standards for IBs, the regulators should also allow the IBs to draw down from their regulatory reserves built during the periods of strong financing growth and their capital conservation buffer of 2.5%.

The regulators can also allow IBs to operate below the minimum liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) and Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) of 100% for a certain period. In this context, IBs could be given a timeline to restore their buffers within a reasonable period after January 2021 to comply with the original requirements.

Moreover, the regulators may also provide some relief to the IBs in terms of NPF threshold for the year 2020 and selected write-off for genuine cases being adversely affected during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The supervisory haircut on collateral values could also be reviewed by the central banks to provide some relief to the IBs in terms of calculating the minimum regulatory capital ratio for the year 2020.

Lastly, regulators can also put restrictions on dividend distribution by IBs until the NPF issues are resolved and all the regulatory requirements are restored.

ROLE OF STANDARD-SETTING BODIES – IFSB AND AAOIFI

The role of standard-setting bodies for Islamic finance such as the IFSB and AAOIFI is pertinent to look at, given the recent developments at their respective counterpart, the Basel Committee and the IFRS.

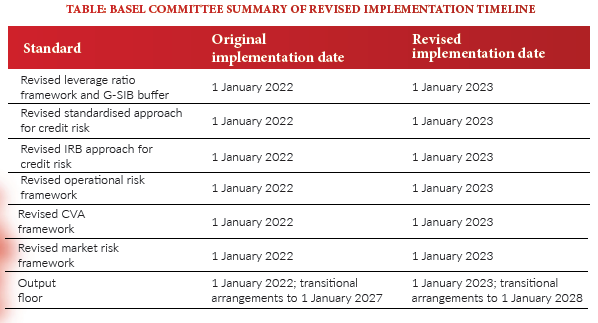

First, on the prudential side, the Basel Committee’s oversight body, the Group of Central Bank Governors and Heads of Supervision (GHOS) has endorsed on March 27, 2020, a set of measures including deferring Basel III implementation (see Table below) to provide additional operational capacity for banks and supervisors to respond to the immediate financial stability priorities resulting from the impact of the COVID-19 on the global banking system:

- The implementation date of the Basel III standards finalised in December 2017 has been deferred by one year to January 1, 2023;

- The implementation date of the revised market risk framework finalised in January 2019 has been deferred by one year to January 1, 2023;

- The implementation date of the revised Pillar 3 disclosure requirements finalised in December 2018 has been deferred by one year to January 1, 2023;

Second on the accounting side, on March 27, 2020, the IFRS has also issued a key statement on the expected credit losses (ECL) recognition and key steps to be taken by the banks in the light of current uncertainty resulting from the COVID-19.

It is worth recalling that IFRS 9 sets out a framework for determining the amount of ECL that should be recognised. It requires that lifetime ECLs be recognised when there is a significant increase in credit risk (SICR) on a financial instrument. Both the assessment of SICRs and the measurement of ECLs are required to be based on reasonable and supportable information that is available to an entity without undue cost or effort. The statement by the IFRS further indicates that in assessing forecast conditions, consideration should be given both to the effects of COVID-19 and the significant government support measures being undertaken. In this respect, several regulators have published guidance commenting on the application of IFRS 9 in the current environment.

In the above context of Basel Committee and IFRS, there is a certain role to be played by the IFSB, and AAOIFI. In particular, IFSB should review the Basel III equivalent standards implementation date, especially the latest document on Revised Capital Adequacy Standard (ED-23, which is still not yet published), and ensure the implementation date for new requirements as per the Basel III to provide a level-playing field to regulators.

On the other hand, the AAOIFI has issued FAS 30 (Impairment Credit Losses and Onerous Commitments), equivalent to IFRS 9 and it should provide some clarity and explanation on the ECL recognition for IBs during this time taking into account moratorium by regulators. The guidance from these bodies would be helpful to the supervisors regulating IBs in their respective jurisdiction.

CONCLUSION

We are facing extraordinary time with this COVID-19 pandemic. Though circumstances are unprecedented, lessons will be learned surely. In such times, both FinTech platforms for IBs and RegTech for regulators are probably winners. As things normalise, economic engines would re-start, people will go back to work, and planes

would take-off. Pandemic like this may become “new normal” in future compared to a “black swan” event. Hence, IBs should pursue agility and resilience. IBs should include such pandemic in their stress testing for sustainability and business continuity.

On the outlook of Islamic finance, being cognizant of this challenge to have a view at this junction; if this pandemic is contained mid of this year; a partial rebound in 2021 could be expected before heading to 2022 for a full-scale rebound. A concerted effort is needed by international bodies such as IFSB, AAOIFI, IIFM, CIBAFI, and IsDB on a coordinated response to COVID-19 for the financial stability of Islamic finance.

While we will see more academic empirical studies moving forward on the actual assessment, IBs should demonstrate compassion during these exceptional conditions. This compassion from IBs’ BOD and senior management should be two-fold: towards customers by giving them some relief and grace period for their debt payments and selfless staff who are at the frontline and/or back office. It is not only time to be kind and compassionate with the staff, but also show kindness to their loved ones by allowing them to work at home with pay.

IBs shareholders should be ready and well prepared for the remedial actions of the above stress testing including strengthening capital buffers. The IBs’ BOD should also provide some flexibility to the senior management on the performance targets for 2020. We should remember that difficult times need extraordinary measures. Together, with unity and resilience, we can all get through this.

Lastly, as this COVID-19 pandemic unfolds, I want to express my sincere thanks to folks – stocking the shelves at the local and those who are in the frontline to provide us services without interruption –who are unsung heroes of the crisis.