Introduction – Islamic debt capital instruments (sukuk)

Sukuk, or Islamic debt security, is generally thought of as the Shari’a-compliant alternative to bonds. Indeed, it was originally created for that purpose: to offer an Islamic alternative to mobilising medium to long-term debt capital. Over a period of time, however, efforts to standardize the industry have also sought to give sukuk a more distinctive Islamic identity, in part by basing them on the principle of risk-sharing, something that has led some observers to compare certain proposed structures to preference shares. Sukuk are different from conventional bonds in the sense that they provide ownership in an underlying asset or project to the investors, unlike conventional bonds, which merely represent a promise by the issuer to repay the loan amount to investors. The issuer of a sukuk provides a financial certificate to investors who are given proportionate ownership of the underlying asset for a pre-defined period. In fact, recent efforts to standardise the market sought to ensure that sukuks have a concrete underlying asset. Moreover, unlike conventional bonds, which provide a fixed interest to bond holders, the sukuk issuer agrees to provide a return to investors in the form of payments that are linked to cash flows generated from the underlying asset for which capital is mobilised. Sukuk issuances can be broadly categorized into:

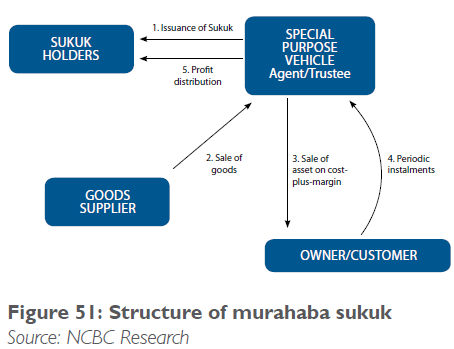

- Murahaba sukuk

This type of sukuk is based on the murahaba form of contract for the sale and purchase of an asset using the cost plus (mark-up) method. It is widely used for short- term financing in trade finance. In the murahaba form of contract, an agreement is signed between the special purpose vehicle (SPV) and the customer according to which the SPV undertakes to buy the asset required by the customer. The SPV then issues sukuks to investors and buys commodities on spot basis from the sukuk proceeds. After that, the SPV sells the commodity to the customer at the spot price plus a profit margin on an instalment basis over an agreed period of time. The sukuk certificate represents a monetary-debt payable by the customer to sukuk holders, the amount of which is agreed initially. Consequently, the secondary trading of murahaba sukuk is not permissible as its transfer to a third party will mean transfer of debt which, according to Shari’a law, can only be exchanged at par value.

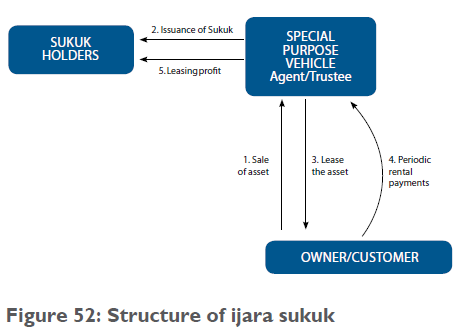

- Ijara sukuk

This type of sukuk is based on the ijara form of contract to buy equipment and lease it to a customer. ijara-based sukuks are primarily used in project financing.

Under ijara sukuk, the customer enters into an asset sale agreement with the third party or an SPV. The SPV or third party acts as an agent/trustee for the investors who fund the purchase. The ownership of the asset is then passed to the trustee on the sale of the asset. The trustee, acting on behalf of the investors, leases the same asset to the customer in return for lease payments from the customer during the leasing period. The leasing profit is then distributed among the investors and the principal amount is paid at maturity. At maturity, the customer purchases the asset from the trustee.

The following are the other prominent form of sukuks:

- Mudaraba sukuk

Mudaraba sukuks are investment sukuks that represent common ownership and entitle their holders share in the specific projects against which the sukuk has been issued. The mudaraba holder has the right to transfer the ownership by selling the deeds in the securities market at his/her discretion.

- Musharaka sukuk

Musharaka sukuks are also investment sukuks and do not differ from mudaraba sukuk except for the relationship between the party issuing such sukuks and holders of these sukuks. In musharaka sukuk, the party issuing sukuks forms a committee comprising holders of the Sukuk who make the investment decisions. These musharaka sukuks can be treated as negotiable instruments and can be bought and sold in the secondary market.

- Istisna’ sukuk

Under the istisna’ sukuk contract, the SPV issues sukuk certificates to raise funds for the project. Sukuk proceeds are then used to pay the contractor/builder to build and deliver the future project. Once the project is completed, the title is transferred to the SPV, which, in turn, sells it to the end buyer. The end buyer pays monthly instalments to the SPV. The profit made from the istisna’ transaction is distributed among the sukuk holders.

- Hybrid sukuk

Hybrid sukuks are the combination of istisna’, murahaba receivables and ijara sukuk. Hybrid sukuks facilitate greater mobilization of funds as they comprise a portfolio of different classes of assets. However, since murahaba and istisna’ contracts cannot be traded on secondary markets as securitized instruments, at least 51% of the pool in a hybrid sukuk must comprise tradable sukuk such as ijara sukuk.

The concept of sukuk as an asset-backed security

Any asset-backed sukuk issuance starts with the identification and segregation of a pool of underlying Shari’a- compliant assets on the balance sheet of the company seeking the finance. Tangible assets such as properties and land are naturally eligible as Shari’a-compliant assets. In addition, most Shari’a supervisory boards have also recognised the eligibility of expected asset-related receivables, not fully identified at the time the sukuk are issued. Ownership rights attached to the pool of assets are then transferred to an ad hoc economic entity, in the form of an issuing SPV that has no capital and seeks to isolate the underlying assets from the “borrower”. The SPV will usually purchase the assets with the in- vestor’s funds, and ultimately the SPV constitutes the legal issuer of the sukuk. The cash payment made by sukuk holders to the SPV as a price for acquiring the sukuk serves as the basis for the issuing SPV to acquire from the originator the rights on the future cash flows to be generated by the pool of underlying assets. Legal or beneficial ownership is passed to the investors, but with a “security agent” or trustee (although there is no recognised trust law in most local jurisdictions).

In current asset-based sukuk, the underlying assets are sold (usually back to the originator at maturity), and the proceeds of this sale are used to pay back the Sukuk principal, usually at a predetermined price. During the lifespan of the sukuk, coupons are served to investors on the basis of the expected returns extracted from the pool of underlying assets. Should there be a gap or mis-match between coupons served and asset returns, the originator or any other external liquidity provider (guar- antor) can make up for such a shortfall – this gives the sukuk the fixed-income characteristics of a conventional unsecured bond. Sukuk issuances can also be subject to some form of “tranching”, like in any conventional secu ritisation transaction, between different classes of sukuk: “senior”, “mezzanine” (or “junior”) and “equity” classes can be issued, depending on their relative creditworthi- ness as reflected in their respective credit ratings.

Whatever the form of the sukuk structure, the legal environment surrounding the issuance is always a key component for analysing risk factors attached to sukuk. Indeed, not only the applicable legal framework, but also the nature of the legal courts expected to possibly handle the eventual disputes emanating from sukuk con- tracts, can to a large extent alter the return expectations of sukuk holders.

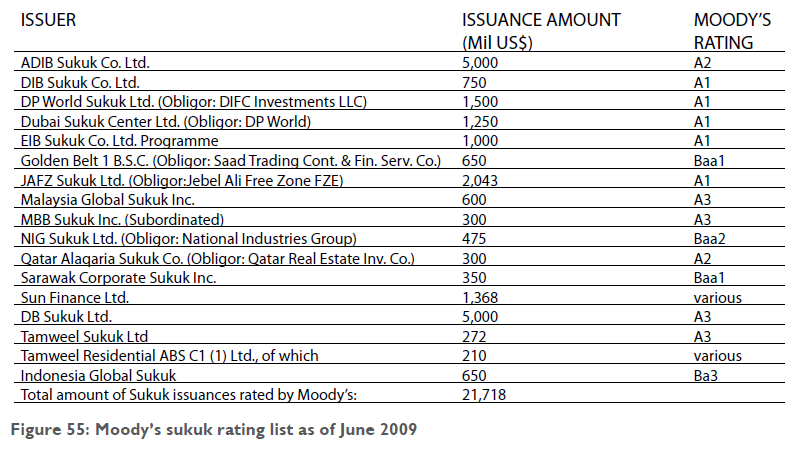

Criteria for rating sukuk distinguish between the broad categories of Islamic bonds

Moody’s assigns ratings to bond issuances, be they conventional or Islamic. The analytical criteria applicable to rating sukuk depend on their nature and characteristics. As shown in figure 54 below, the analysis distinguishes between two broad categories of structures under which sukuk may be issued, and which dictate to a large extent the applicable rating methodology.

The first category of sukuk includes all Islamic bond issuances that benefit from the originator’s guarantee. Such sukuk are said to be “asset-based”, where- by asset transfer is essentially in form rather than in substance.

The second sukuk category comprises sukuks that do not benefit from the explicit support of the asset originator. Such sukuk are said to be “asset-backed” to reflect the fact that the most critical rating factor lies in the credit quality of the underlying assets. Here the asset transfer is effective in substance and not just form.

This distinction determines the eligible ratings approach. In short, the first category of sukuk usually attracts ratings that reflect both the creditworthiness of the originator providing the guarantee and the ranking the sukuk compare to the originator’s other senior unsecured obligations. The ratings on the second category of sukuk are a function of the credit features of the assets underlying the whole sukuk structure.

The main analytical feature of unsecured asset-based sukuk lies in the fact that both coupons and principal reflect an unconditional and irrevocable obligation of the originator. In cases where the underlying assets gener- ate insufficient cash flows to pay the coupons (periodic distribution amounts) to sukuk investors, the originator, as asset manager and guarantor, makes up the shortfall and serves coupon payments to sukuk holders.

At the sukuk maturity, the originator repurchases the sukuk underlying assets at a predetermined price, equivalent to the sukuk principal. In this case, the sukuk rank pari passu with all other obligations of the originator, senior or subordinated, depending on the rank of the guarantee. Most of the rated sukuk in this category constitute senior unsecured obligations of originators- obligors, and by way of consequence their ratings have been equalised with the originators’ issuer ratings. So far, very few subordinated sukuk have been issued and rated.

Secured asset-backed sukuk, on the contrary, are subject to an analytical treatment similar to that applicable to bond classes emanating from securitisation transactions. This means that the ratings on, those secured asset-backed sukuk, like those on securitisation tranches, essentially depend on the economic and financial attributes of the pool of underlying assets, not on the creditworthiness of their originator. One of the many benefits of Islamic securitisation transactions giving birth to secured asset-backed sukuk is the ability of the originator to issue sukuk rated higher than the originator’s issuer credit ratings.

The intricate history of sukuk

Although the concept of sukuk has been discussed in the Islamic finance literature for over a decade, the first modern sukuk prototype was only pioneered in 2000, at the 11th Islamic Development Bank Annual Symposium.

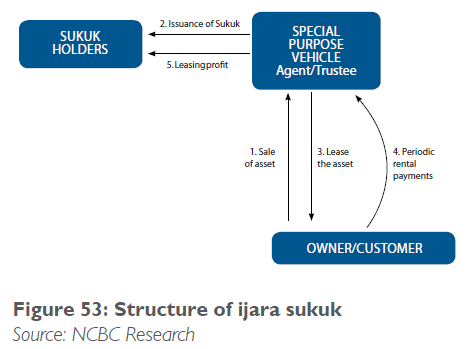

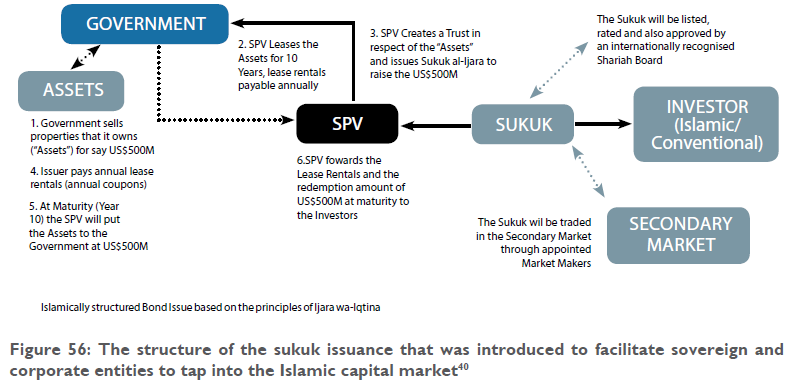

- The ijara sukuk structure essentially requires the corporate to sell certain physical assets to a SPV, which would then lease the assets back to the corporate for a certain number of years

- The SPV will issue sukuk certificates to investors and raise the required funds to pay the corporate for the physical assets.

- The corporate will receive the sale price at the time of the sukuk issuance, and will pay the periodic lease rentals, usually every 6 months, to the SPV for the duration of the lease.

- The SPV will distribute the periodic lease rentals to the sukuk holders as coupon payments under the sukuk (comparable to bond coupon payments).

- At maturity, the SPV will sell the assets back to the corporation at the original sale price, (not at market or fair value).

- The SPV will pay the sale price received from the corporate to the sukuk holders and the sukuk will be redeemed. Given that the rental payment and sale price at maturity are the direct obligations of the corporate, the risk/reward profile of the sukuk is comparable to that of a conventional bond. This allows the sukuk to then be priced on par with a conventional bond.

Although the structure of the sukuk, the pricing formulae and the risk/reward profile are all quite straightforward and appealing, the sovereign and corporate entities faced several challenges in issuing this sukuk. One major challenge was the lack of suitable assets for the underlying ijara transaction. Most sovereign entities were reluctant to relinquish public assets to foreign investors due to the negative sentiments this would create in the public. The sovereign entities preferred the conventional bond route which did not require any disposal of assets from the sovereign. The corporate entities on the other hand either did not have suitable assets, or the assets were not sufficient or already encumbered, or such disposal was subject to transfer taxes. Hence, although the ijara sukuk is structurally viable and legally possible, the product did not receive much initial interest in the Muslim world.

Finally in 2001, the State of Bahrain tested the sukuk waters by offering its inaugural ijara sukuk issue in the domestic market. The issue amount was US$ 250 million and had a tenor of 5 years. The sukuk carried 6-monthly lease rentals which were fixed at the lease inception and paid in arrears during the lease term. The sukuk was backed by US$ 250 million worth of sovereign assets. The Bahrain sukuk issue was a major milestone in Islamic finance as it marked the dawn of the sukuk capital market. It also demonstrated to other Muslim sovereigns that the sale of sovereign assets for the purpose of sukuk issuance would not be perceived negatively by the public. However, the Bahrain sukuk documentation did not meet international bond standards, and was not rated or listed or cleared through any clearing house. The Bahrain sukuk issue was hence mostly subscribed by domestic investors.

Subsequently in December 2001, Kumpulan Guthrie Berhad, a Malaysian public listed company involved in the plantation and construction sector, issued an ijara sukuk. The company offered a US$ 150 million sukuk issue with a floating rate of return. The tenor was divided into 3 years (US$ 50 million) and 5 years (US$ 100 million). The sukuk was backed by underlying land assets in Malaysia worth more than US$ 150 million. Unlike the Bahrain Sukuk, the Guthrie Sukuk was documented in accordance with the internationally recognized US Regulation S format, and was listed on the Labuan International Financial Exchange. However, the Guthrie Sukuk was neither rated by the likes of Moody’s, S&Ps or Fitch, nor was it cleared through any clearing house. Again, the Guthrie Sukuk did not achieve a wide distribution in the international capital markets.

The Birth Of Asset based Sukuk

Malaysia, having successfully developed its domestic Islamic bond market, was eager to help create the international Islamic bond market. In 2002, the Federation of Malaysia created history by issuing the first Islamic global sukuk that complied with the US Regulation S and Rule 144A formats that are used for conventional global bonds. The Malaysian ijara sukuk was the first sukuk to be listed on the Luxembourg Stock Exchange and rated by S&P and Moody’s. The US$ 600 million sukuk was offered globally to both Islamic and conventional investors including ‘Qualified Institutional Buyers’ in the United States. The issue was a huge success and was two-times oversubscribed. The Malaysian sukuk was a significant development because it was able to successfully fuse the concept of ijara sukuk with the conventional bond practices of listing, ratings, dematerialized scripts and centralized clearance.

The Malaysian sukuk was backed by US$ 600 million worth of sovereign assets like government administrative buildings, hospitals and academic institutions. The asset-backed sukuk structure created a major legal constraint for the Federation of Malaysia. Unlike the State of Bahrain and Kumpulan Guthrie, the Federation of Malaysia had previously issued international bonds and some of them still remained unredeemed in 2002. All international bonds have a standard negative pledge which restrains the bond issuers from issuing any bond in the future that is not in pari passu with the existing un-secured bonds. Given that the Malaysian international bonds were all unsecured bonds, the proposed sukuk issuance was seen as a direct breach of the negative pledge clause, given that the sukuk would be backed by the ownership of the underlying assets. The sukuk effectively becomes a secured bond, and will be given priority over all unsecured bonds of the Federation of Malaysia. The Federation of Malaysia was advised not to proceed with the sukuk until all the outstanding bonds were redeemed. The development of the sukuk market almost came to a standstill.

With the help of a few prominent Shari’a scholars, the Federation of Malaysia found a neat solution to avoid breaching the negative pledge. Under the revised struc- ture, the sukuk holders will have beneficial ownership of the assets held through the sukuk trustee during the life of the sukuk. This will meet the Shari’a requirements of asset ownership46 under ijara principles. However, in the event of default by the Federation of Malaysia, the sukuk trustee’s sole recourse to the assets is to dispose the assets only to the Federation of Malaysia and seek payment. The sukuk trustee will not have the power to retain or sell the assets to any third party. Once the sukuk trustee has disposed the assets to the Federation of Malaysia, the sukuk holders will in law be treated as un- secured creditors. The revised sukuk structure therefore was not seen as asset-backed securities, although the su- kuk did have underlying assets. The Malaysian sukuk became known in the market as “asset-based” securities.47 The sukuk is based on Shari’a-compatible assets, but the sukuk holders will only be able to dispose the assets to the lessee and no one else. This was not viewed as an ideal solution by many, but given the prevailing circumstances, it was the only viable solution.

Today, almost all sukuk offerings are asset-based securities. The sukuk will have Shari’a-compatible underlying assets but the sukuk holders will not have any security interest over the assets. The asset-based sukuk are treated as senior unsecured securities similar to unsecured conventional bonds.

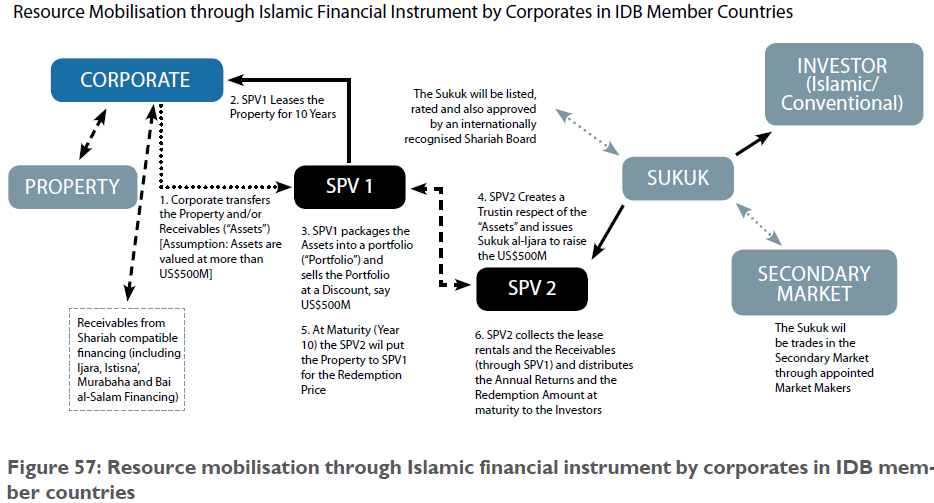

The dawn of “blended assets” sukuk

When the sukuk concept was first conceived in November 2001, it was also envisaged that not all corporate issuers will have sufficient Shari’a-compatible physical assets for the ijara transaction. The following structure was recommended for corporate issuers who have Shari’a-compatible receivables as well as physical assets. The structure shown in figure 57 above requires that the corporate sells both physical assets and receivables to an SPV (“SPC 1”) which will in turn lease-back the physical assets to the corporate. The SPC 1 will then combine the receivables and physical assets (leased-back to corporate) into a single portfolio and sell the entire portfolio to another SPV (“SPC 2”). SPC 2 will then hold the portfolio on trust and issue sukuk to investors. The sukuk holders will be treated in law as the beneficiaries of the trust portfolio, and this meets the Shari’a requirement of ownership. Although receivables and other forms of debt cannot be transferred except at par value under Shari’a, if the receivables are combined with physical assets in a single portfolio then the entire portfolio can be sold at any price48. This type of combination is structured based on the concept of khulta. The main condition for such portfolio is that the proportion of the physical assets has to be more than the receivables. Some Shari’a scholars require the majority portion to be at least 51% and others insist that it should be at least two thirds of the portfolio.

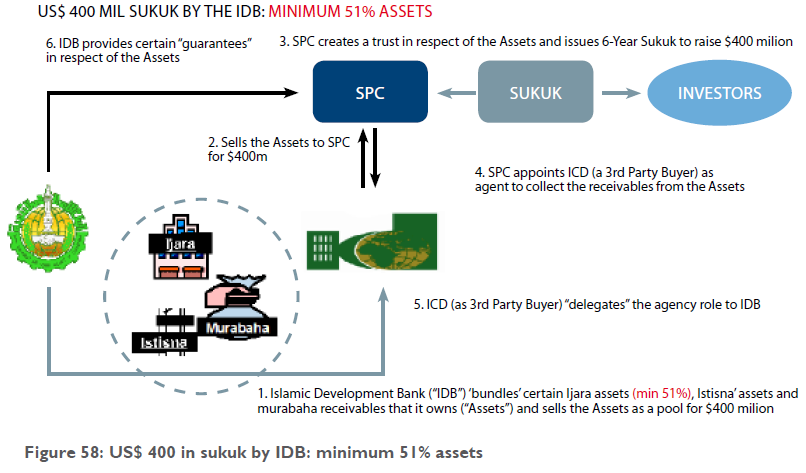

In 2003, the Islamic Development Bank (IDB) seized the opportunity to test the viability of the “blended assets” sukuk structure, and successfully issued a US$ 400 million sukuk. Like all financial institutions, the IDB had less physical assets and more Shari’a-compatible receivables on its books. The “blended assets” sukuk approach was the only viable solution to the IDB, if it wanted to succeed in its resource mobilization strategy. The IDB sukuk was structured as follows:

In the IDB sukuk, the mixed portfolio consisted of ijara assets comprising 65.8% of the portfolio (although the minimum requirement was set at 51%) and murahaba and istisna’ receivables comprising 34.2%.49 The 65.8% of ijara assets comprised of certain physical assets owned by the IDB and which have been leased out to various counterparties. Since the ijara assets can be freely transferred at any price by the IDB, by mixing the murahaba and istisna’ receivables (dayn) with ijara assets (ayn) the IDB was able to transfer the receivables as well.

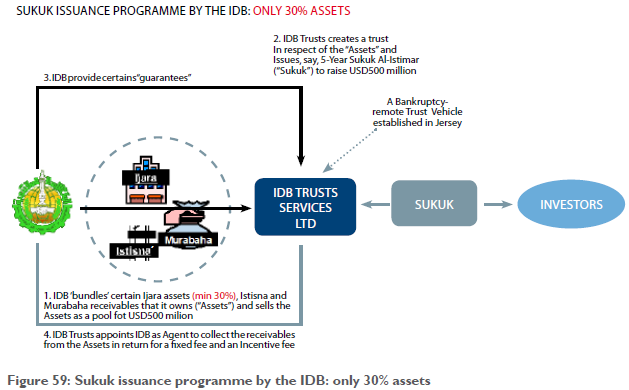

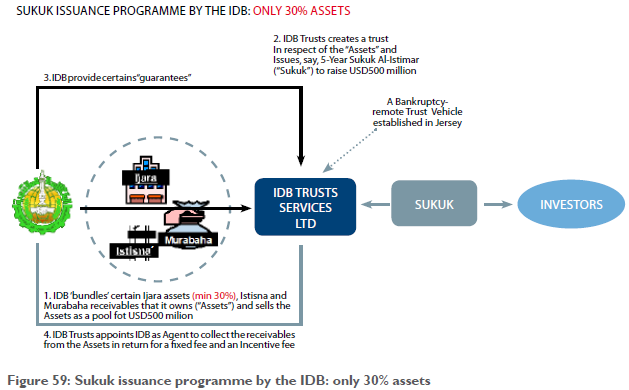

The IDB sukuk issue was well received by the market and subscribed by both Islamic and conventional accounts. A few years later, the IDB went to the market again and this time, the IDB appeared to have even less physical assets to inject into the mixed portfolio. The IDB wanted to reduce the proportion of ijara assets from 65.8% down to 30%. In the past, some Hanafi scholars have taken a more liberal view of the khulta principle. They have not allocated any fixed percentage or quantity, but have left the matter to be decided on a case-by-case basis. Hence, there may be circum- stances where even if the non-compatible component is more than 50%,50 the object can still be considered on a whole Shari’a-compatible. Based on this view, the IDB was permitted to sell a mixed portfolio consisting of only 30% physical assets. The subsequent IDB sukuk was hence structured as follows:

The Influx of “Asset- light” Sukuk

Whilst the “blended assets” sukuk structure has been a tremendous boost for institutions like the IDB and US$ 400 MIL SUKUK BY THE IDB: MINIMUM 51% ASSETS

SUKUK ISSUANCE PROGRAMME BY THE IDB: ONLY 30% ASSETS

other Islamic financial institutions to tap the sukuk capital markets, others found the prevailing sukuk structure constraining and unviable. These corporations either could not meet the 30% physical assets requirement or they did not have any Shari’a-compatible receivables. Many of these corporations were in an expansion mode fuelled by the massive economic boom in the Middle East. The corporations were keen to tap the ever growing and liquid Islamic finance market and were severely constrained by the asset requirements for the sukuk issuance. With the help of a few Shari’a scholars, a new sukuk structure was conceived and launched out of Dubai. The new sukuk was called a musharaka sukuk, and was structured as follows:

In the sukuk structure shown in figure 60 above, the Dubai Metals and Commodity Exchange (DMCE) needed US$ 300 million to develop a land that it owned. DMCE and the SPV formed a musharaka where DMCE contributed capital in the form of land worth US$ 48 million.51 The issuer contributed capital in cash equal to US$ 300 million and issued a musharaka sukuk to the investors to raise the required funding.

In return for the capital contributions, each musharik was allocated a certain number of musharaka units equal to the value of their capital contribution, (essentially representing shares). The musharaka then appointed DMCE to use the US$ 300 million cash contribution to develop three offices and residential towers on the land in accordance with the musharaka business plan. The musharaka business plan stated that the various individual units in the 3 towers will be sold or leased by DMCE to potential customers on behalf of the musharaka. The proceeds of the lease rentals and sale considerations would be utilized to pay the 6-monthly periodic distributions (viz. the coupon payments) and the final distribution at maturity (viz., the last coupon payment).

Unlike the Bahrain, Malaysia and IDB sukuk issues, there was no principal redemption feature (where the initial sukuk issue amount is repaid to redeem the sukuk) in the DMCE sukuk structure. Instead, the initial sukuk issue amount of US$ 300 million was amortized in 10 instalments of US$ 30 million which is paid as consideration for the purchase by DMCE of 1/10th of the musharaka units owned by the issuer every 6 months.53 DMCE provided a legal undertaking to the issuer to buy the US$ 30 million worth of musharaka units every 6 months until all the musharaka units of the issuer have been transferred to DMCE.

The above sukuk structure raises the following Shari’a concerns:

- Is the musharaka sukuk tradable?

One of the Shari’a requirements for trading sukuk at premium or discount to face value is that the sukuk must represent substantial physical assets. What amounts to substantial assets has varied over the years from 100% in Bahrain, Guthrie and Malaysian sukuk, to 30% in the IDB “blended sukuk”. If we compare the Shari’a standard used in Islamic equity investments, the total receivables and cash in a company must not be more than 33% of the total assets. If the company has more than 33% cash or 33% asset receivables, the equity of the company will be considered as non-Shari’a compatible. The rationale behind the standard is that if the company has more than 33% cash or account receivables, the shares of the company will essentially represent cash or debt (dayn) which, from a Shari’a perspective, cannot be traded except at par. This standard equally applies for sukuk which is also a tradable instrument.

In the DMCE sukuk, the musharaka venture had US$ 48 million worth of physical assets and US$ 300 million worth of cash. The total asset of the venture was US$ 348 million and accordingly the ratio of cash to total assets was around 86% at the inception. In all like lihood, the cash will be utilized over a period of two to three years in line with the progress of the construction of the three towers.55 Even in the most remote event, where DMCE (as agent of the musharaka) had paid the entire US$ 300 million in one day to the contractors of the three towers, the musharaka venture would still end up having assets receivables worth more than 33% of the total assets. According to the offering circular, more than 80% of the two towers have already been pre-sold by DMCE prior to the sukuk issuance. Given that all the rights over the three towers have been transferred to the musharaka venture, the purchase price payable for the pre-sold units will become assets receivables of the musharaka venture. A back of the envelope calculation will show that the value of the receivables for the presold units comprising more than 80% of the two towers will surely be more than 33% of the total assets.

Hence, the musharaka sukuk should not be traded except at face value until the time when the three towers have been completed.56 Unfortunately, this important aspect of the Shari’a seemed to have been completely ignored and the sukuk was permitted to be traded at a premium or a discount to the face value.

- Is it permissible for DMCE to undertake to buy from the issuer the musharaka units at par value every 6 months?

In musharaka and mudaraba arrangements, it is a well-established rule that one partner cannot guarantee the return of principal or the share of profit of the other partner. The rationale behind this rule is that if say, partner A undertakes to buy the musharaka share of partner B, the capital contributed by partner B will be regarded under the Shari’a as a loan from partner B to partner A, and if partner B receives any share in the musharaka profits, such profit will be deemed as riba (interest). The Shari’a strictly requires that any loss suffered by the musharaka venture should be shared by all partners in proportion to the capital contributed. Hence, if partner A contributes 14% and partner B contributes 86% of the capital of the musharaka and there is a loss of say, US$ 100, partner A will be accountable for US$ 14 and partner B for the remaining US$ 86. The Shari’a does not allow the partners to mutually vary the loss sharing ratio under any circumstances. For example, if partner A agrees with partner B to absorb say, 50% of the losses, such an arrangement will not be permissible under the Shari’a.

In the DMCE sukuk, DMCE had irrevocably undertaken to buy US$ 30 million worth of musharaka units of the issuer at par value every six months. The undertaking is legally enforceable by the issuer regardless of whether the musharaka venture has suffered any losses or not. Let us assume that the construction of the three towers did not go as planned or DMCE was unable to sell or lease the end units of the three towers. In such an event, the musharaka venture is likely to suffer significant losses. However, any such losses will be borne solely by one musharik, DMCE. The issuer will not be suffering any losses given that it will be able to sell its share of musharaka units to DMCE at the pre-agreed price of US$ 30 million every six months, until its entire mush-araka units have been bought by DMCE. The irrevocable undertaking by DMCE effectively guarantees the full principal repayment of the musharaka investment made by the issuer. This arrangement goes against the very grain of a musharaka contract as recognized by Shari’a.

The proponents of the DMCE-type of sukuk (“asset-light sukuk”) contend that the irrevocable undertaking is permissible under Shari’a for the following reasons:

DMCE had solicited the investment from the issuer based on the business plan that it had submitted;

DMCE had represented that it had conducted adequate due diligence on the business plan and it is confident that the musharaka venture will be successfully carried out as per the business plan;

If the musharaka venture does not go as planned for whatever reason, the rebuttable presumption is that such failure is due to DMCE’s own failure in conducting proper due diligence or in implementing the musharaka venture as per the business plan; and DMCE should be solely responsible for such failure or losses unless the presumption in paragraph (iii) above is rebutted by DMCE.

The above reasoning does appear rather convincing. Why shouldn’t DMCE be responsible for its own failure to conduct the musharaka venture as per the business plan? The Shari’a does provide that if a musharaka venture suffers a loss solely due to the negligence or wilful default of say partner A, it is perfectly lawful for partner B to seek full indemnity from partner A. However, if partner A can establish–usually in a court of law—that he was neither negligent nor in wilful default, then there will be no indemnity from partner A to partner B. Both partners will bear the losses in proportion to the capital contributed.

However, a deeper analysis of the asset-light sukuk documentation reveals the following:

The sukuk investors are not privy to the business plan and in reality, pay hardly any attention to the business plan.

Whilst the undertaking by DMCE to buy the issuer’s musharaka venture is irrevocable and invokes the presumption of negligence or wilful default on the part of DMCE should there be any losses in the musharaka venture, the documentation is completely silent on how such a presumption can be rebutted by DMCE. For example, if say DMCE had completed the three towers fully in accordance with the business plan but, due to the ongoing global financial crisis, failed to sell or lease the end units as set out in the business plan. In such an event, the presumption will be that DMCE had been negligent in selling or leasing the units and hence should be responsible for the losses suffered by the musharaka.

The documentation does not provide any opportunity for DMCE to rebut the presumption and avoid being responsible for the losses. This type of irrefutable presumption is clearly not permissible under Shari’a. The Shari’a would have allowed DMCE to rebut the presumption by, for example, establishing that the failure to sell or lease the end units was solely caused by the global financial meltdown which was unprecedented and completely unexpected at the time the business plan was prepared.

DMCE is likely to fail in the English courts if it refutes this presumption on the basis of Shari’a, given that the documentation is totally silent on this matter. The English courts have emphatically stated that in relation to Islamic finance contracts, it would only look within the four walls of the documentation to ascertain the intention of the contracting parties. The English courts have refused to apply the principles of Shari’a law, given that the Shari’a is not the recognised law of a state, and there are different interpretations of the Shari’a given by the various schools of jurisprudence.

Based on the analysis of the DMCE sukuk documentation, it appears that the rationale offered by the proponents of the asset-light sukuk does not however apply to the DMCE sukuk itself. But, what if the sukuk documentation were to provide that DMCE shall be entitled to rebut the presumption of negligence or wilful default and be released from the irrevocable undertaking to buy the musharaka units from the issuer? In theory, this is clearly possible. But in reality, such a clause will cause serious concerns among the sukuk investors who only want to assume the credit risk of DMCE. Any potential risk linked to the viability of the business plan will mean that the sukuk investors are assuming quasi-equity type of risk in addition to the credit risk of DMCE. Such additional risk will not be attractive to sukuk investors who are mostly fixed-income investors. Such risks may appeal to equity investors but in return for the risks they will demand a higher return on the sukuk, which in turn will not be attractive to DMCE. Hence, from a practical perspective, it is extremely remote for any musharaka sukuk documentation to contain such provision. It is therefore not surprising for the DMCE sukuk documentation to be totally silent on such a critical Shari’a provision.

What happens if the musharaka venture fails to generate sufficient profit to meet the periodic distribution amount?

Another critical Shari’a issue was the ability of the musharaka venture to generate sufficient profit. One of the cornerstones of a mudaraba and musharaka contract is that while the partners are at liberty to agree on any profit-sharing ratio between them, no partner can guarantee the profit share of another partner. Any such guarantee will be tantamount to riba. In the DMCE sukuk, DMCE and the issuer agreed to share the profit generated by the musharaka venture based on an 80:20 ratio. However, another caveat was that if the issuer’s share of profit is greater than the pre-agreed benchmark rate, DMCE will be entitled to the surplus as a form of incentive fee. Through the incentive fee mechanism, the DMCE sukuk was able to cap the profit share of the issuer and transfer any potential upside to DMCE.

If the musharaka venture is unable to generate any profit, the DMCE sukuk provided that DMCE will seek Shari’a-compliant funding, at its own account and without any recourse to the musharaka partners or mush- araka assets, to ensure that there is sufficient liquidity to make the six monthly periodic distributions.60 Although its permissibility under Shari’a is debatable, the liquidity facility mechanism appears to be a neat solution that protects the downside risk of the issuer.61 Further, if DMCE fails to pay any of the six monthly periodic distributions it will trigger an early dissolution of the mush- araka and DMCE will be obliged to immediately buy all the remaining musharaka units of the issuer. This mechanism also further reduces the musharaka downside risks of the issuer. All these new features put together had ingeniously transformed an equity-type musharaka investment into a debt-type fixed-income investment.

Although the DMCE sukuk had serious Shari’a issues, the simplicity of the structure and the easing of the Shari’a requirement for physical assets had created a lot of excitement in the nascent sukuk market. Corpora- tions seeking to tap the liquid Islamic market suddenly found an easy way to issue a sukuk. All they required was a good credit rating and a business plan. It was almost too good to be true for both the issuers and the investors. The sukuk market suddenly saw an exponential growth with the issuance of multi-billion dollar sukuk offerings. Many jumbo-sized sukuk, including the following notable issues, have all been made possible by adopting the asset-light sukuk structure:

US$ 1.4 billion mudaraba sukuk by DP World, UAE US$ 2 billion musharaka sukuk by JAFZ, UAE

US$ 2.5 billion exchangeable mudaraba sukuk by Aldar Properties, UAE

US$ 3.5 billion convertible musharaka sukuk by PCFC, UAE

US$ 4.5 billion musharaka sukuk by Binariang GSM, Ma- laysia

The backlash from AAOIFI

In February 2008, the Shari’a board of AAOIFI, having deliberated on the various Shari’a issues raised by the asset-light sukuk, issued a ruling which effectively banned the asset-light sukuk. Unfortunately, the AAOIFI ruling, due to poor drafting, lacks clarity and fails to shed sufficient light on the rationale for the ban.

The AAOIFI ruling is summarized as follows:

In order to be tradable, sukuk must exhibit evidence of the ownership in Shari’a-compliant tangible assets (like real estate) and/or intangible assets like usufruct (e.g., leasehold rights) or services (e.g., toll road concessions);

in order to be tradable, sukuk must not represent any receivables or debt unless the sukuk represents (i) the entire business of a Shari’a-compliant trading company or an Islamic financial institution or (ii) the portfolio of existing Shari’a compatible tangible and/or intangible as- sets which incidentally also includes some Shari’a compatible receivables; the sukuk agent cannot offer or procure any liquidity facility if the profits generated are insufficient to service the periodic distributions payable to the sukuk holders; neither the agent nor the partner in wakala, mudaraba or musharaka sukuk is permitted to undertake, at maturity or upon an early dissolution of the sukuk, to buy the shares (or the shares’ underlying assets) of the other partner(s) at the initial face value. Such undertaking is however permissible if the price is based on the prevail- ing market value or fair value (if there is no market value) or at a price to be mutually agreed at that time; and in ijara sukuk however, the lessee is permitted to undertake to buy at the initial face value the leased assets from the leasing company at maturity or upon an early termination of the lease provided the lessee is not act- ing as a partner, mudarib or an investment agent of the leasing company.

The above ruling has effectively put an end to the dramatic growth of asset-light sukuk issuances. Without an undertaking to buy the shares of the sukuk holders at par value, it is highly impossible to issue an asset-light sukuk. Since the AAOIFI ruling in February 2008, there has not been any asset-light sukuk offering in the market. However, it is not obvious whether the lack of such of- fering is due to the AAOIFI ban or the unprecedented credit crunch caused by the global financial crisis. It is hoped that the dearth of asset-light sukuk is due to the AAOIFI ban. The sukuk market was rather quiet in 2008 with hardly any significant sukuk offering in the Middle East or the Far East.

Back to basics

In the first half of 2009, the sukuk market witnessed some green shoots emerging. The Republic of Indonesia successfully issued its inaugural US$ 500 million ijara sukuk which was oversubscribed to the tune of US$ 3 billion. The Kingdom of Bahrain also returned to the market to successfully issue another ijara sukuk which closed at US$ 650 million. And in August 2009, Petronas, the Malaysian national oil company also successfully issued its debut benchmark ijara sukuk issue. The Petronas sukuk was launched at US$ 1.5 billion and was five times oversubscribed. Interestingly, all three sukuk issues were structured as asset-based ijara sukuks, and carried fixed rental rates. Hopefully, the AAOIFI ban had played a key role in shifting the market away from asset-light sukuk. However, it is still too early to declare the demise of the asset-based sukuk and only time will tell whether the market has taken the AAOFI ruling seriously. The success of the Indonesian, Bahrain and Petronas sukuk issues clearly demonstrated that the asset-based sukuk is still the most viable and attractive option to issuers. The shift to asset-based sukuk will certainly add more credibility to the sukuk market and help the industry to gradually progress towards a Shari’a-based financial system. The sukuk industry is still at an early stage and has a long way to go. Hopefully, its future path will be clear of asset-light sukuk issues.