Introduction

The universe of available funds considered, held in cash or securities and bearing a recognized fatwa, is said to have reached over US$ 950 billion at the end of 200817. Of this, however, no less than 74% is said to be within commercial banks, meaning less than US$ 250 billion is in assets outside murahaba and cash deposits. Among that sum not more than US$ 50 billion is in funds of all kinds, excluding assets in investment banks, which we assume are tallied as PE funds. At 10% of the total, in- DVDVD investment bank assets of also US$ 50 billion illustrate the mismatched allocations between mutual funds and PE. Rarely anywhere, anytime, have PE assets equaled mutual fund assets. This will be discussed in more detail below. If we extrapolate from 2009 data in the Capgemini- Merrill Lynch World Wealth Report, we can see that about US$ 2.5 trillion of managed assets worldwide are owned by Muslims, albeit nearly all of which must be conventionally managed since not even US$ 100 billion exists in Islamic mutual funds and PE (murahaba and cash, of course, cannot be considered as managed as- sets). This indicates that Muslims have only placed 4% of their managed assets into Shari’a-compliant investments, of which half is in mutual funds and half in PE funds. Put another way, 96% of Muslim wealth is managed conventionally, and only 2% is invested in Islamic mutual funds. Clearly this indicates extraordinary potential for growth. We need to remind ourselves there is no easy way to extract reliable numbers in this industry. No single source offers a full and complete summary of Islamic investment products. Here, we have patched together in-formation from public sources, as well as compiled our own data sets, but we are certain the numbers are far from perfect. Readers may only want to use these numbers indicatively. However poor the data, we can still guess gross allocations of Shari’a-compliant assets and make comparisons to conventional assets in developed and developing economies. We can also with some justification declare whether there are mismatches be- tween world standards for conventional asset allocation and those found in the Islamic asset universe.

Given that predominantly or wholly Muslim countries are by and large emerging economies, where nominal savings rates are as high as 5% of GDP per year, one can conclude substantial new money for investing is produced every year, at least in the range of US$ 250 billion or more (assuming a conservative US$ 5 trillion annual GDP for the Muslim world, which does not include net new savings of Muslims in non-Muslim countries). Total offshore savings accumulated since the late 1970s by the private sectors of Saudi Arabia and the Arabian Gulf region should now easily be well above US$ 1 trillion.

One could further extrapolate from that sum a total of up to US$ 200 billion held under managed accounts in Switzerland alone, and that much or more in savings held in North America and Europe.

This rough data is provided only to indicate that the sums of money under discussion are not trivial, regardless of whether we can exactly determine the size of Muslim savings. There can be no disputing the availability of large volumes of money that could be directed towards Islamic investment products, now and well into the future.

But, where in fact do most Muslims place their savings? From our extrapolations above we can see they are not by and large investing in Shari’a-compliant assets, and far from it. We can only assume that the vast majority of Muslim savings are either in cash, conventional deposits, and conventional investments.

We have done our own informal search for Islamic assets. Initially this effort cast a wide net, tallying anything that could be found and categorized as an “Islamic investment” via some form of fund vehicle or another. At this level we discovered over 900 such funds, with total AUM reaching almost US$ 80 billion.

However, our tallies did not discriminate. In fact we needed to filter out any investment product that did not meet professional tests for suitability. Asset management is, after all, the professional allocation of a client’s funds into investments to meet planned objectives. Non-qualifying assets must be rejected by professional asset managers as unsuitable for their client accounts. And, if a fund is unsuitable to professional investors, then by extension it is unsuitable for just about every- one else.

Such filtering is common in the conventional asset management industry. Many proprietary platforms permit only funds meeting certain minimum criteria to be included. Such platforms can multiply several-fold a fund’s distribution reach. For example, there are many criteria to be adopted by the Credit Suisse Fund Lab platform. Gaining access to this platform allows a manager to achieve potential distribution of his product throughout the Credit Suisse system, which is not small. The criteria for mutual funds (of any kind) generally used are as follows (but not exclusive):

- Minimum US$ 100 million AUM

- Not less than three years operating history

- Clear, transparent and frequent reporting

- Short-term liquidity, i.e., not more than one month

- Easy cross-border international clearing and settlement through one or more mechanisms (e.g., Clearstream)

Unfortunately, if one applied the above criteria to the larger universe of Shari’a-compliant products on our database, which contained over 900 Islamic funds, one would find not more than 15 or 20 qualifying Islamic funds.

Naturally this would lead any asset manager to abandon efforts to allocate a client’s funds into Shari’a-compliant assets. However, we can expand the universe of qualifying funds by being less restrictive, but still within the boundaries of professional responsibility:

- Minimum US$ 25 million AUM

- Not less than two years operating history

- Clear, transparent and frequent reporting

- Short-term liquidity, i.e., not more than three months

- Easy cross-border international clearing and settlement through one or more mechanisms (e.g., Clearstream)

- Fatwa from respected sources (i.e., no irregular fatwa from unrecognized scholars)

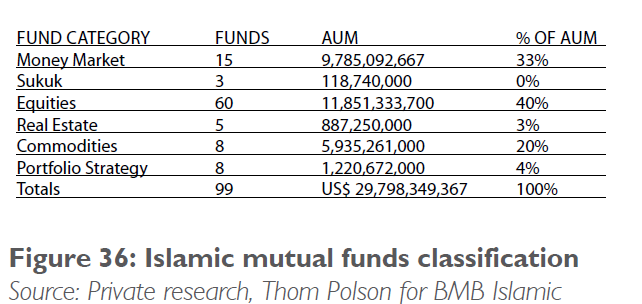

Using these less restrictive criteria we can identify 99 funds with a total AUM of nearly US$ 30 billion. While this is not a sizeable universe, it is a workable universe if one can make the concessions necessary (e.g., smaller minimum fund size and less liquidity).

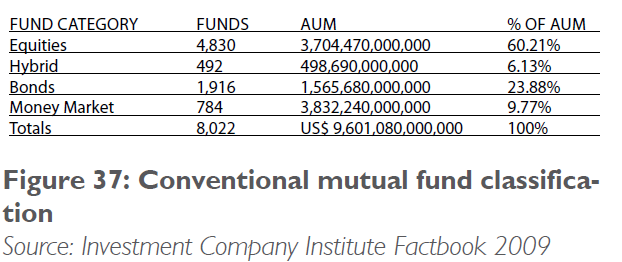

We bring this to the attention of readers because we have learned that the Investment Company Institute Factbook 2009 shows there is almost US$ 19 trillion AUM in mutual funds worldwide among nearly 70,000 funds, an astonishing figure in comparison to Islamic mutual funds, whether measured from the larger or more restricted universe discussed above.

The image of the Islamic mutual fund industry becomes even more skewed when considering the allocation of assets among various classes, from money market to real estate:

Here we see that among qualified Islamic mutual funds there is an abundance of money market and equity funds, but almost no sukuk funds and very little in alternative investments.

It is useful to make comparisons to the conventional mutual fund space only in the United States, an economy with a very high absorption rate of mutual funds across all social and economic spectra.

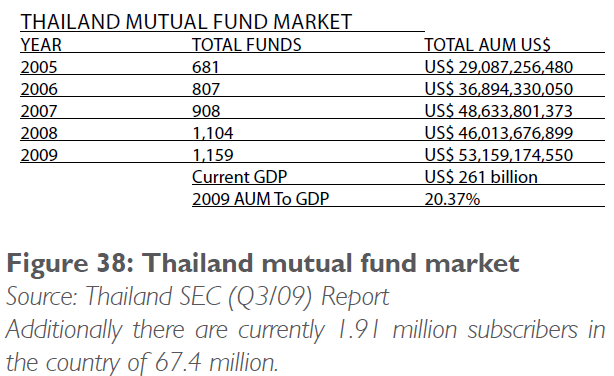

It is of course unfair to compare an emerging asset class like Islamic mutual funds with the advanced and mature US mutual fund industry. But, it is instructive to see where the Islamic mutual fund industry may go. We know that many emerging markets follow the same trajectory when adopting non-native systems to local economies. The adoption of mobile phones follows a trajectory not dissimilar from the adoption of mutual funds. In fact, many emerging economies have already achieved relatively high levels of mutual fund adoption, such as the achievement of Thailand’s mutual fund AUM which equals to just over 20% of GDP.

Private Equity Funds

If there are over 900 Islamic fund products with US$ 80 billion in AUM, but only 99 Islamic mutual funds with under US$ 30 billion, then where is the difference?

In our tabulation of investment products we discovered a very large number of minuscule funds, with AUM un- der US$ 10 million or even under US$ 5 million. We also discovered literally several hundred funds that appeared initially to be qualifying mutual funds, but had to be rejected when in fact they were disguised private equity.

One example is the sukuk Fund from a relatively important bank in Kuwait. From its label one would assume it is a fund comprising various sukuk, managed on a portfolio basis, to provide a risk/return profile similar to a bond fund.

Further reading, however, shows the fund invests solely in a single timeshare property in Mecca, has more than 12 years to maturity, and is mostly illiquid. It also pays a 30% performance fee to the fund manager.

Clearly this can only be classified as a private equity fund. Yet the label knowingly or not confuses the reader into thinking it may be a replacement for fixed-income al- locations in a portfolio.

There are numerous similar examples of funds that at first glance appear conventionally structured as mutual funds, but in fact fit into the private equity category.

We have glanced at the annual reports of many of the largest private equity houses in Arabia (there are more than 100 in total now, from just a handful in 2000). Surprisingly, it appears that just four or five of the biggest names in the region’s private equity industry raised over US$ 50 billion in AUM from 2003 through to 2007, or nearly double all AUM in qualifying Islamic mutual funds. When considering where the money went, we conclude the vast portion of funds raised in the last decade, the “missing” US$ 50 billion, went into private equity investments.

Sukuk funds

What is striking from the above data and exclusive to the Islamic mutual fund space is a heavy leaning towards low-risk cash and high-risk equities. There seems to be little in between. For example, we can consider two of the three sukuk funds that qualify under our interpretation. In fact neither of these two would be acceptable to, for example, a Swiss private banker managing assets for a family in Jeddah. One is Pakistani, denominated in rupees, and may not be available outside its home jurisdiction. The other is not only in Saudi riyals and available in Saudi Arabia, it’s also a mixed fund, with both murahaba and sukuk, meaning it’s not a sukuk pure play.

Interestingly, there is only one dollar-denominated, professionally managed sukuk fund with global distribution (domiciled in the UAE) that meets our standards, but its AUM is barely above our limit at US$ 26.9 million. Another professionally managed pure-play sukuk fund comes from Saudi Arabia, but surprisingly its AUM is around US$ 15 million despite having been founded in 2007.

With an estimated US$ 2.5 trillion or more Muslim AUM (not including Muslim-owned funds in non-Mus- lim countries, such as Geneva or London) one would expect at least 40% could be reasonably expected to be managed according to Shari’a, or at least US$ 1 trillion. If among let’s say 33% was invested in Islamic mutual funds (in line with developed country averages of mutual fund assets to total managed assets), then the Islamic mutual fund industry would boast today approximately US$ 330 billion in AUM. If among that there were a “normal” allocation of 25% to fixed income, or sukuk fund, allocations, then one could reasonably expect no less than US$ 82 billion to be invested in sukuk funds. Yet when adding all sukuk and quasi-sukuk fixed-income style funds together we have only 12, including the smallest fund at just barely US$ 1 million in AUM, we have just over US$ 200 million in AUM, or 2.5% of the potential worldwide market.

Equity funds

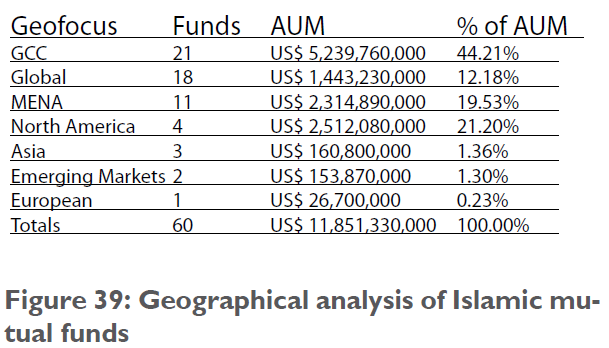

Let’s turn our attention now to Islamic equity mutual funds. Here we find 60 mutual funds that meet our slightly lowered professional criteria with a total of US$ 11.85 billion AUM. There are literally hundreds more Shari’a-compliant equity funds, but we have excluded those that cannot be purchased without exposing the manager to potentially damaging professional liability, i.e., too small, too illiquid, non-transparent, etc.

Obviously the data shows a richer, deeper collection of funds from which a professional manager might select assets for his clients. However, looking deeper into the data we realize there is only one fund managing Euro- pean equities that meets our professional criteria, and only two defined as “emerging market.”

Worse still, we see a whopping US$ 2.5 billion in AUM among Islamic mutual funds invested in North American funds (primarily the United States). A significant skew is evident here, as the money is invested in only four funds and out of these four one fund accounts for US$

- billion invested or 58% of all the North American Shari’a-compliant equity funds.

As one would imagine there are 39 mutual funds in- vesting in the GCC region and the broader Arab world (with several funds including Turkey as eligible for MENA investing), illustrating again a home bias for investors from the region. To emphasize this, GCC and MENA equity funds combined have almost 64% of all AUM in Shari’a-compliant qualifying funds.

Other funds

As indicated in the sidebar above, finding a definition of many Shari’a-compliant mutual funds can be problematic. The example used—a so-called sukuk fund that in fact is PE for a single real estate asset—indicates the difficulties in targeting assets for professional allocations. Other funds include real estate and commodities, where our data mining and filtering captured five real estate and eight commodity funds. However, among these it is very difficult to determine whether any or all of the real estate funds are still liquid. One of the largest such funds from a major global bank’s Islamic subsidiary closed its doors to redemptions in late 2008, thereby forcing removal from our list. Among the commodity funds are five exchange-traded funds, or ETFs, which arguably are not classically managed mutual funds at all but something else entirely.

Total AUM in the real estate category of qualifying funds was US$ 887 million, thereby far exceeding AUM in the sukuk category. And, AUM in the eight commodity funds was US$ 5.9 billion, but with the proviso that only US$ 1 billion was in classic managed funds, US$ 1.4 billion in exotic metal ETFs, and the lion share of US$ 3.5 billion in a single physical gold ETF.

Diversification in a single fund.

In our research we found eight funds which fit this category and met our professional filtering criteria, from as small as US$ 36 million in AUM to as large as US$ 385 million. Total AUM in the category was US$ 1.22 billion. However, here again we see significant skew in the data. Of the US$ 1.22 billion in strategy funds we find only US$ 166 million in fully diversified global investing. The remainder is focused within the GCC or wider MENA regions, with little or no investments outside. A professional manager trying to achieve global diversification amongst a large pool of smaller-sized private client accounts would have difficulty achieving his objectives using these relatively small funds.

Asset allocation

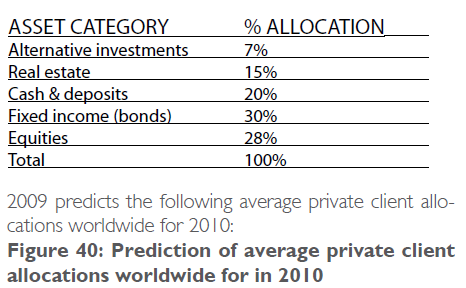

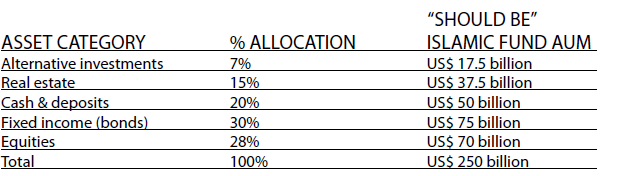

The Capgemini-Merrill Lynch World Wealth Report

2009 predicts the following average private client allocations worldwide for 2010:

Now let’s take figure 40 and consider what would be the case if 40% of the US$ 2.5 trillion in estimated global Muslim-managed wealth was invested according to Shari’a, and 25% of that amount was invested in Shari’a-compliant mutual funds.

Clearly the volume of Shari’a-compliant investment funds has yet to make any meaningful impact on the total potential market for managed Muslim money. With just under US$ 30 billion in AUM today, we may conclude that the Shari’a-compliant mutual funds market is currently capable of absorbing another US$ 220 billion in AUM to meet 40% of the potential Muslim-owned managed wealth market.

Areas of potential growth

This data indicates an immature industry requiring a nearly ground-up construction. At the same time, it is clear Muslims are for the most part spiritual, and seek to envelope all aspects of their lives in a fashion that corresponds to Shari’a. Investing personal or institutional funds according to Shari’a is no exception, but very slowly and increasingly the rule in all parts of the Muslim world.

It is important to note that Islamic mutual funds have the ability to become the great equalizer in the Islamic investment sphere. PE is and always must be the realm of the ultra-rich investor with specialist investment advisers. Buying sukuk is prohibitively expensive for most people because of minimum transaction sizes of US$ 1 million or more. Hiring your own investment management team is also prohibitively expensive for most people. Mutual funds allow large numbers of people to pool small amounts of money and achieve through scale economies professional investment results. Mutual funds of any kind are generally defined by low subscription costs and a good level of service regardless of how many shares one holds. Mutual funds achieve a social good by providing professional investment skills and resources to even the most humble man.

Shari’a itself is no mystery. It is simply a set of rules guiding investments toward community benefit, and away money market instruments, known as murahaba. One of these is the essential fictitious nature of underlying commodity assets, which we will not delve into here. However, a major area of growth would be to develop murahaba substitutes, in particular against short-term assets. There is no shortage of such assets in the Mus- lim world, nor in the developed world. Perhaps there is “stickiness” when some Muslim clients consider whether to invest their short-term liquidity into a conventional deposit or a murahaba, a question of confidence. But, with potentially US$ 50 billion at stake there is little doubt murahaba and murahaba substitutes could be vastly greater in total AUM than they are today.

Fixed Income: Today there are only about US$ 110 billion in outstanding sukuk, which is the foundation of any Shari’a-compliant fixed-income strategy fund, but many sukuks have been increasingly viewed as toxic because of their preponderant link to real estate, in particular in places such as Dubai and Bahrain, where real estate valuations have plummeted. If one were to reduce total sukuk to only those guaranteed by sovereigns or strong corporations the actual value of sukuk outstand- ing could be just a few dozen billion. One can reduce the qualifying sukuk even further by separating Malaysian from non-Malaysian sukuk, which would result in per- haps less than US$ 20 billion in sukuk that would meet professional standards today. If the sukuk market truly picks up, with billions of new issuance, we may eventually see the minimum US$ 75 billion needed to fulfil potential demand.

Real Estate: The less than US$ 1 billion in managed real estate funds today pales in comparison to the potential US$ 37.5 billion that could be produced and distributed to Muslim investors. One bright spot on the horizon is the potential introduction of Islamic REITs to the Gulf In late 2007 there were four hedge funds launched off Equities: By far this investment has made the most progress in developing qualifying funds. But, as evidenced by the nearly US$ 60 billion in demand there is much room for progress. Interestingly, before the financial crisis there were about 2,500 stocks on the Dow Jones Islamic Market Index comprising about US$ 17 trillion of global market capitalization, or almost half of all share capital in the world. One would expect that US$ 11 billion in managed equities versus a pool of US$ 17 trillion in qualifying equities illustrates the immature nature of the Shari’a-compliant equity mutual fund industry.

Alternative Investments: As previously mentioned, there are large commodity ETFs, arguably however they are not managed assets. There were some Shari’a-compliant hedge funds, but their status today remains unknown. Clearly with nearly US$ 18 billion in potential demand the gap is enormous. PE, which consumed perhaps US$ 50 billion of investor funds in Arabia over the period 2003 through to 2007, may not be much of a source for filling the alternative space. PE houses in the GCC region will require years to overcome the substantial losses of client and shareholder capital recently experienced.

Barriers to growth

These asset classes unquestionably have to grow further in order to create a stable investment environment for the Islamic funds industry. However, this is not the only answer to the dilemma. The 99 funds we qualified for professional investing still have not proved themselves on the world stage. Most were developed and sold for local markets, not sophisticated international investors. We do not have to reinvent the wheel for success to be achieved; just adapt what is already in place in the conventional funds market.

Islamic mutual funds are identical to conventional mutual funds, with the exception of a fatwa issued at the time the fund is created and Shari’a monitoring taking place annually thereafter; which in itself is not a particularly time consuming nor expensive process. Just as there are specialists picking assets for bond funds, equity funds, hedge funds and the like, the same security selection process takes place in Islamic funds. There is no shortage of analysts and fund managers with the skills and abilities to perform these tasks.

A prime example is the Dow Jones Islamic Market in- dex, which uses simple computer filters to screen over 4,500 listed shares worldwide to find 1,700 or so that are suitable for Shari’a-compliant investing. While their volumes are small and their impact almost insignificant, there are several major global banks that have created a dozen or so Islamic funds to serve clients seeking Shari’a-compliant investing.

The failure to achieve wide distribution and large volumes of AUM seems to be solely a commercial one, not in any way technical. The few major global banks that have created a handful of Islamic funds seem to have done so only for a very limited client base in a very limited geographic area; the GCC region. None has yet to add the resources for wider distribution of more mainstream products.

- This seems counterintuitive for a faith that claims over billion adherents, of which we are certain some tens or even hundreds of millions want and need Shari’a-compliant investment products. The United States, Europe and even Russia have combined Muslim populations of around 50 million. Predominantly Muslim populations exist in North Africa, Central Asia and Southeast Asia. Yet outside of Malaysia and perhaps Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, no Muslim can walk into his local bank and purchase a diversified portfolio of Shari’a-compliant mutual funds.

This puzzling situation defies a straight explanation. Some bankers contend that because of the varying schools of Muslim thought, no single fatwa can be obtained to satisfy everyone. But, a fund manager can, obtain several fatwa for his investment product, thereby achieving a much wider acceptability than a single fatwa. Other bankers declare that in reality Muslim clients don’t care about Shari’a compliance; that it’s a media-driven demand and not real demand. This could have been true, but logically can’t because we’ve seen total assets in the Islamic banking system grow at double digits annually. This growth can’t be simply because a few bankers want more money, but only from true demand among a wider population.

Yet other bankers state that Muslims want Shari’a-compliant investing, but they become disillusioned if they need to sacrifice in order to buy Islamic; sacrifice in terms of performance, liquidity, or transparency. But, we’ve already shown that Shari’a-compliant investing doesn’t need to have any different outcomes in any of these categories. Neither liquidity nor performance nor transparency has anything to do with a fund being Islamic. The cost of Shari’a compliance is miniscule for funds above US$ 20 million, which logically is where all investors of any faith should draw a line of acceptability (or even higher, like Credit Suisse Fund Lab).

Perhaps one source of forcing growth of Islamic mutual funds is governments. They have the regulatory power to stimulate more Shari’a-compliant funds. They have captive savings in the form of central bank reserves, agency treasuries, pension funds, social endowment treasuries, and a host of other piles of investment money that could increasingly be dedicated to buying world-standard investment products with fatwa. Imagine only the size of the Abu Dhabi, Qatar, Kuwait and Saudi sovereign wealth funds or captive treasuries—collectively over US$ 2 trillion—and you can imagine how quickly the banking community would respond if they were forced to deliver professional products that also were Shari’a-compliant.

What’s at stake for governments is the efficient allocation of capital in fast-growing economies, at least in the GCC region. No one disagrees that mutual funds play a significant role in allocating capital between savers and users of capital, and that without mutual funds economies face handicapped growth prospects. Mutual funds are some of the most efficient financial intermediaries ever devised, allowing risk and reward from investing to be distributed throughout an economy and indeed throughout the world.

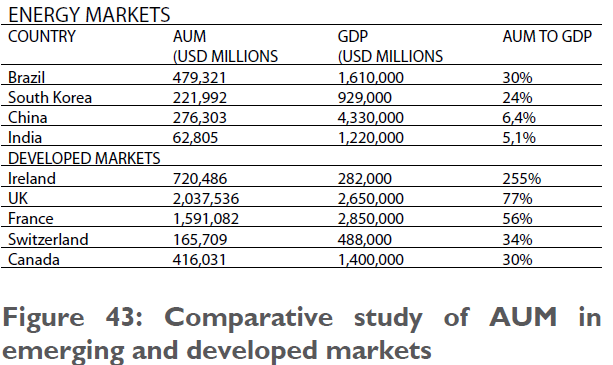

In highly developed economies, AUM in the mutual fund industry reaches or exceeds 100% of GDP. Developing economies have a trend towards international standards over time, so eventually mutual fund AUM in developing economies is expected to reach the same level as in developed economies.

For Muslim states that desire a mutual fund industry based on Shari’a concepts, there are indeed no barriers to achieving very high levels of absorption of national savings in mutual funds. What is missing is simply the commercial will among the banking community to deliver.

Unfortunately, as noted above, more local money in Arabia over the last seven years has been invested in IPE than in Islamic mutual funds, a situation that baffles any observer as PE worldwide amounts to fewer than 2% of global managed wealth. These expensive, feeladen, high-risk investment funds should have remained a niche category, but achieved household status literally overnight. We are beginning now to see the unwinding of this imbalanced situation, with bankruptcies threatened

throughout the GCC region among some of the most prominent names in PE. The pendulum does appear to be swinging, hopefully to a more rational allocation of capital: plain-vanilla Islamic mutual funds.

Let’s look at one economy where mutual funds have achieved some of the highest penetration rates in the world, the United States. Here we see mutual funds owned by tens of millions of the “common man” but also owned by the elites, and amounting to almost US$ 10 trillion in total assets.

Because of a homogenous regulatory environment and standardization, US mutual funds are easily definable and accessible to people of all income levels. There is widespread public education, by both the private and government sectors, on the benefits of owning mutual funds. Tax laws are written and enforced that stimulate everyone from households up to buy and hold mutual funds.

The Investment Company Institute Factbook 2009 points out that 30% of all Americans own mutual funds and 59% of those acquired their first fund through em- ployer-sponsored programs. And, Americans are known to buy and hold their investments for long time periods. Yes, they periodically are bitten with the speculative bug, but overall they lock a considerable portion of their retirement savings in the form of mutual funds. And, Americans are not alone. Western economies have mutual fund AUM anywhere from 50% to over 200% of GDP. We can see in many advanced develop- ing countries a trend towards these levels, in particular in Brazil, Russia, India and China, and also in South Korea, Turkey, Malaysia and Indonesia. Rarely does one see a mutual fund AUM below 5% of GDP in an advanced developing economy. On the other hand, a 2009 SAMA report shows that of all funds on offer in the Kingdom, less than 2% of the population has subscribed. Clearly Saudis are either not informed about the benefits of investing for the long term, or they have somehow developed investing behaviour contrary to their own interests. If this is the case then we need to look at regulators and banks for an explanation.

Distribution

The Islamic mutual fund industry has the potential to become large and meaningful if it follows several simple prescriptions. The first is to keep products simple and straightforward. Instead of the conventional money market, bond, stock and alternative investment funds you have murahaba, sukuk, stock and alternative investment funds. No Islamic fund should be any different in performance, liquidity, or transparency to its conventional counterpart.

We’ve already explained that delivering such products to market is relatively easy. There are no technical barriers in doing so, and no great cost.

Where we find the single greatest weakness in the Islamic mutual fund industry is distribution, or perhaps the commitment to come up with products and then see them distributed on a wider basis.

Anecdotally, we can point to some of the few large Islamic mutual fund providers in Arabia and see that none have a permanent sales presence outside their home markets. Few of them approach Geneva, with its tens of billions of managed Muslim savings, to sell Islamic mutual funds.

There are several Islamic banks in London now, but outside a very small number of products (to date we can only identify two or three Islamic funds from Islamic banks in London) they have produced nothing of substantive value to professional asset managers, and none of these products appear to have anything but the most simple form of distribution. Certainly none have yet at- tempted to penetrate the Arabian, Malaysian, or even the Swiss markets with Islamic mutual funds.

On further reflection, one may take the example of the mutual funds powerhouse BlackRock, a firm that over two decades went from literally zero AUM to over US$ 3 trillion and in the process becoming the largest asset manager in the world by nearly all measures.

BlackRock didn’t achieve global sales and distribution with fancy new products, the highest performing products, nor by any other feats of magic. They simply focused on distribution of a family of funds that met professional standards. They achieved enormous market penetration by partnering with financial institutions, employers (for employee retirement accounts), endowments and even charities, all of whom needed reliable but perhaps a bit mundane mutual funds.

In a perfect world there would be a BlackRock-type of Islamic mutual fund company perfecting the art of cross-border distribution as BlackRock has done, and penetrating through every corner of the Muslim world with plain-vanilla investment products that people need. Imagine if any Muslim country achieved only half the mutual fund penetration rate of the United States, or 15%. Then we’d see 1.3 million investors in Kazakhstan, 3 million in Syria, and 4.8 million in Morocco.

Why have Islamic mutual funds not achieved distribution success to date? In large part it may be due to the overwhelming amount of time, media coverage, re- sources and attention that was paid to the IPE houses in Arabia since early 2003. Certainly we know these same high-risk, illiquid businesses attracted tens of billions of dollars of investor funds, while at the same time Islamic mutual funds did about the same or less; a lopsided result that still befuddles.

Going forward we can summarize some of the determinants of a successful Islamic mutual funds industry, and the path to get there.

All Muslim countries, and other countries with large Muslim populations, are potential targets for creating, managing and distributing Shari’a-compliant mutual funds. We can assume the future targets include several hundred billion dollars of AUM and tens of millions of investing clients. Logically this is where the industry must go.

Distribution is key. Managers of Islamic mutual funds must consider the success of firms like BlackRock and attempt to achieve similar results. This involves partnering with many institutions capable of distribution, but most importantly with banks that have highly developed branch networks, like Habib Bank in Pakistan with over 1,400 branches in a country of 175 million persons. Partnerships keep operational costs low.

Partnerships also fill the need for client due diligence and servicing. We have seen such partnerships working for years in Saudi Arabia, in particular past relationships between Fidelity and Deutsche Bank with various Saudi banks. Employee-sponsored mutual fund purchase programs should be envisioned. As mentioned, 59% of US mutual fund investors bought their first fund through employer-sponsored programs. Large employers are critical for mass, but all employers can benefit from such programs, with side benefits like employee retention also a consideration

Takaful insurance is another partnership target. Many of Europe’s largest fund families, as well as their American counterparts sell vast volumes of mutual funds through insurance partnerships. Takaful premiums are said now to be only around US$ 3.4 billion annually, but are expected to grow to over US$ 7.7 billion by 2018.

Broker/Dealer networks are another primary source for partnership distribution. To date it appears no mutual fund family has been offered for distribution to the literally hundreds of broker/dealer operations in GCC, from Kuwait to Saudi Arabia to the UAE. These local broker/ dealers already have relationships with investors, from the smallest to the largest, from which a strong sales case can be made for Islamic mutual funds.

Swiss distribution must be on any list of priorities for an Islamic mutual funds program. Asset managers in Switzerland opt for allocations on a fund-of-funds basis for smaller accounts, typically under US$ 10 million. Over the past two decades mutual funds and many other kinds of fund managers have penetrated the veritable Swiss market and made enormous progress in selling their products. Considering that Switzerland could have as much as US$ 200 billion in Muslim AUM, and that there are today literally no offerings of Shari’a-compliant products across the investment spectrum, one could consider this market among the most important of them all. These are only a few of the examples of the creative thinking that needs to go into the wider, cross-border distribution of Islamic mutual funds. There is little doubt that most Muslims would prefer a Shari’a-compliant investment to a conventional investment if Muslim investors knew they need not sacrifice performance, liquidity, or transparency. Anyone who develops products meet- ing world standards, and understands the key point of distribution, can achieve sizeable AUM in short order.