Introduction

It’s official – everyone wants a piece of the halal action. If it’s for rewards in the hereafter or revenue generation in the here and now, achieving halal status is something that many businesses are exploring. Halal as a means for delivering competitive advantage is considered to be an x-factor which can help to expand operations, creating new markets and drawing in more consumers.

In the shadow of the economic downturn, halal has also been able to increase brand value, relieve constraints associated with barriers to entry, and stabilise fluctuating markets. Muslims, like other ethnic segments, such as the Afro-American Market, are seen to exhibit stronger signs of loyalty trans-nationally which in some cases has acted as a catalyst to draw in wider non-Muslim communities. From this, it can be argued that halal presents an adaptation of existing management and brand thinking.

Traditionally, halal was largely held to be self-evident, through the idea that the majority of things are halal according to the Quran. Where matters necessitated further investigation, conclusions were rarely derived from branding. Instead, an assessment of halal arose from examining ingredients, the environment and the involved individuals. However, with so many products and services on the market, from so many sources, it is inevitable that branding becomes of greater significance. Brands are conspicuous – they differentiate, inform and reassure.

Furthermore, whilst it could be argued that Muslim minorities and non-Muslim nations should have a greater need for such labelling and reassurances, this trend also extends to Muslim nations and Muslim majority populations. Halal fever has gripped the psyche of the Muslim consumer and it could be argued that businesses are also reaping the rewards of Muslim piety and risk aversion. So much so that halal as a descriptor is being used for more and more commodities, services and activities. Without looking at simply ‘meat and money’, halal is even being used to describe, amongst other things, milk, water, non-prescription medicine, holidays, washing powder, tissues, cosmetics, websites and music.

The key questions now are:

- How does halal fit into the branding world, if at all?

- What branding approaches work and can be used?

- How much knowledge and how many practitioners exist, with sufficient cross-functional skills, to champion both the halal and branding?

- Who sets the agenda?

- How can halal marketing and branding move forward?

This chapter considers these questions and takes a look at some of the challenges currently being faced.

The halal landscape

Halal in its general sense can be translated as meaning allowed or permissible. A basic acceptance and understanding of what is halal is central to every Muslim’s belief, falling under the umbrella of what is considered to be information that is known by necessity. A general rule of Islamic jurisprudence holds everything as halal unless stated otherwise with the exception of meat. Therefore, a Muslim who has a sound grounding in Islam should be able to identify what is halal and what is not. In contrast, haram appears to resonate in the eyes of individuals with much stronger sentiments. This is because the conscious consumption of, or engagement in, haram activities, without repentance, carries the risk of spiritual or physical punishments (within Islamic law, or in the hereafter). As a result, Muslims tend to adopt a position of avoidance in the face of doubt. In Malaysia, the term non-halal is used in preference to haram in the signage of non-Muslim restaurants. This appears to confirm the perceptions of the word haram encouraging censure by both Muslims and non-Muslims.

Current literature, largely housed within product marketing, indicates literalist and uniform definitions of what is halal. However, halal, as a concept, contains within it attributes which render it both a phenomenon and a noumenon. Halal’s roots pre-date formalised marketing and branding practices. What is deemed halal is ultimately governed by the heavens and subsequently can never remain in its entirety within materialist branding frameworks. Instead halal is a philosophy which, whilst apparent in branding, marketing and product development, stretches much further into disciplines such as management, organisational behaviour, psychology, cultural anthropology and sociology. Following this, management practices and processes concerned with the halal should also take into account the implicit views of all stakeholders and this is where its true potential lies. In addition, whilst there are numerous denominations within the Islamic faith that agree upon the halal/haram dichotomy in principle, in practice they struggle to both agree and implement such universals. In light of these factors, a call to bring forward one halal brand as something that will fit all remains problematic.

Defining Islamic marketing and branding

In appraising halal branding, connected terms such as “Islamic Marketing”, “Islamic Branding”, and “Muslim Brands” also have to be considered. All are still relatively new, and reflective of a need to define an emergent phenomenon which stretches across the Muslim world and beyond. Furthermore, its interest and applicability has garnered support from a wider community regardless of faith. As such, there are varying perspectives and standpoints, which have raised discussions as to how this phenomenon should be understood and, moving forward, should be researched and served by practitioners.

Debates continue to question what Islamic marketing actually means. For example, does it only consider how marketers should communicate with Muslims? Or whether you have to be a Muslim to even execute Islamic marketing? The fundamental difference is that now the field is more than simply marketing a religion, or marketing to the faithful. It might be worth considering whether many activities are in fact “Islamic Marketing” or “Islamish Marketing”?

An allegory can be drawn with the phenomenon of marketing to Afro-American consumers, or “Black Entertainment.” Those consumables which were targeted, or held to be specific to the Afro-American, or “black” community, such as food, fashion, hair cosmetics, music, comedy and film, are mainstream commodities demanded by a wider core non-Afro-American or black audience.

Taking these into account, a working definition of “Islamic Marketing” can be seen as:

- An acknowledgement of a God-conscious approach to marketing from a marketer’s and/or consumer’s perspective, which draws from the drivers or traits associated with Islam.

- A school of thought which has a moral compass tending towards the ethical norms and values of Islam, and how Muslims interpret these from their varying cultural lenses.

- A multi-layered, dynamic and three-dimensional phenomenon of Muslim and non-Muslim stakeholder engagement, which can be understood by considering the creation of explicit and/or implicit signalling cultural artefacts facilitated by marketing.

Thus, what is branded halal and marketed is definitely more than simply “meat and money”. Muslims like any other consumer segment or sub-culture love fashion, entertainment, cosmetics and holidays – and these are potentially seen as being halal. But perhaps most importantly a key question is whether marketing is shaping Islam, or in fact is Islam shaping marketing? In principle, Islamic marketing covers a range of approaches and sub-disciplines by treating marketing as an inclusive term then narrowing down practices to those which affect Islam and Muslims. Conversely, an alternative view could be taken is that Islam is a source of reference in the broadest sense which drills down on marketing. However, this is not a new question; through examining Chinese studies and management, as a corollary, the same questions were asked. Therefore, the argument presented here is that the first phase of development sees marketing theory applied to Islam. Following this, as Islam presents a wider paradigm, it is likely that Islamic guiding principles will overtake those of marketing.

Creating halal brands

If halal is treated as a brand, it is unlikely that the name halal could be adopted outright. Therefore, its usage positions it as an ingredient brand or compound word, almost assuming the role of a co-brand (e.g. Halal- OtherWord, or OtherWord-Halal). As a co-brand, there

is scope for a global organisation creating a corporate division which utilises the term halal. However, this would bring more of an organisation’s practices under further scrutiny, such as the treatment of employees and their working environment. For service providers, food would have to comply with halal specifications and more efforts would have to be made to preserve Islamic rituals, such as fasting and prayer.

Whilst this may appear to be a bold step, it could in fact be an effective strategy when entering Muslim countries by reducing mistrust and consumer distance. Through this ring-fencing, organisations can distil their strategies, removing the potential for over-kill as individually branding each product offering with halal will reduce the term’s efficacy. Such approaches would be a departure though from basic Islamic principles where everything is halal unless stated otherwise. However, they may serve as cues encouraging and reassuring stakeholders of their halal legitimacy.

The challenge of producing halal commodities on a wide scale will always pose problems. Better quality products delivered more quickly for lower costs and with a stronger brand presence do not constitute what is considered halal according to definitions derived from Islam. The drivers for creating halal commodities lie in Muslim involvement, correct thinking, intentions and ethical practices.

Illustrating this, the following chapter in the Qur’an and three sayings of the Prophet form the cornerstone of Islamic judgements:

“I (Allah) swear by time, that I have created, that all of mankind is at loss; except for those that (do all of the following): believe (in Islam), do good deeds, guide people to truth and have patience.” (Qur’an, chapter 103)

“All actions are judged by intention.” (Bukhari and Muslim)

“Whoever commits an act, or introduces a matter into our religion (Islam), which is not part of it, will have it rejected.” (Bukhari and Muslim)

“Allah’s Messenger (Prophet Muhammad) cursed ten people in connection with (alcoholic) wine: the wine- presser, the one who has it pressed, the one who drinks it, the one who conveys it, the one to whom it is conveyed, the one who serves it, the one who sells it, the one who benefits from the price paid for it, the one who buys it, and the one for whom it is bought.” ( Tirmidhi)

Whilst the drinking of alcohol for recreational purposes is prohibited in Islam, the last hadith also demonstrates that the involvement in, encouragement and consumption of this commodity is also forbidden. Therefore, an argument is made to encourage the decommoditisation of halal concepts in favour of treating them as processes where the behaviour and intentions of those involved also fall under scrutiny. This would push practices towards approaches such as corporate altruism, sustainability and green marketing. Following this, further consideration would have to be made as to which products and services would credibly still remain within this reworked halal framework. Products which profess such levels of ethical practice tend to position themselves as carrying a premium. In contrast, many current halal offerings adopt strategies that price them below their non-halal equivalents, if not cheaper. This is to encourage their consumption either for religious or commercial reasons (and in some cases both). In addition, it would appear that halal, as a concept, is able to achieve resonance amongst Muslims away from being a brand. However, brands that abuse the term halal may in fact weaken the strength and resonance of their offering by losing credibility amongst consumers through over commercialisation.

Halal brands specifics

Halal brands need to consider two aspects beyond Shari’a compliance: the principles of Islamic design ethics and the heritage of culturally-influenced historical interpretations of these principles by Muslims.

It could be assumed that this is a simple case of using Arabic calligraphy, words and semiotics strongly associated with Islam such as the star and crescent moon, or Islamic geometrical patterns. However, whilst these might evoke a response, recognition and association, there is little empirical evidence as to what degree these resonate and elicit the desired response. In support of this point, it is apparent that non-Muslim brands fare well amongst Muslims. And, where there is an overtly Islamic alternative, it remains unclear as to what strengths and weaknesses the brand possesses and where the perceived value lies. At both ends of the spectrum, Fast Moving Consumable Goods (FMCG) and high-end luxury brands from Europe, North America and Japan are able to command a premium beyond the functional quality of the commodity. They have also been able to use this brand equity and trust as a platform to create Muslim/cultural-centric offerings. Examples of this can be seen with designer label hijabs, cultural foods, and cosmetics with extracts such as black seed or honey. Brands which are Muslim at their inception have tried to replicate these successes, but often are perceived as “copy-cats” to their detriment. It might be thought that their weakness lies in the fact that the product is similar, but instead it is argued that their weakness lies in brand strength and uniqueness which, whilst being able to deliver something authentically Muslim, lacks brand sophistication and sufficient human-like attributes. In the modern world of global outsourced manufacture, many commodities can achieve the same levels of quality, design and functionality; however, branding is a tool that offers the greatest differentiation and can elicit greater subjectivity, which leads to trust, credibility and desirability.

Following this point, there are cases of halal brands and commodities that have embraced a wider vision and in doing so have expanded the remit of what an Islamic brand looks and feels like. Some brands have preferred to use English fonts which allude to Islamic semiotics not just to ensure wider appeal, but because they understand that the pull of other cultures is significant. Recently, this can be seen with the popularity of hip-hop culture and graffiti amongst Muslims. The calligrapher Haji Noor Deen fuses Chinese calligraphy and brush work with Arabic. Research by MarkPlus Inc. highlights that Islamic banks in Indonesia have found greater success when moving away from creating an Islamic identity which is rooted in Arabic. It is likely that this trend will increase, with the majority of Muslims not being native Arabic speakers, and business and the Internet strongly being reliant on the English language or alphabet communication. Many Arabic/Islamic terms are transliterated into other languages and there is an argument for the design of more halal brands embracing the same trend. This may face opposition, as there is an argument for this weakening a cornerstone and strength of Islam, which is the unification behind Arabic. However, designers have to decide whether their role of creating compelling and effective halal brands is more important than the preservation of the Arabic language, and as an extension the gateway to understanding sacred texts. The suggestion is that both could be achieved by some brands, but not by the majority, and that this is a different strategic objective which may not be appropriate for all commodities.

When considering the specifics of promoting a halal brand, it can only be ascertained once the brand architecture and the competitive environment have been established. Just because a brand is deemed to be Islamic, it does not follow necessarily that there is one set of guiding principles. Just as Muslims evaluate their core principles and how these are practiced and conveyed within society, halal brands have to do the same. Therefore, it may be possible for halal brands to use conventional promotional mechanisms. Conversely, if the environment is unsuitable- for example, the level of opposing editorial content or advertising messages in a media source- then it might make more sense to abstain. A way to circumnavigate these could be to favour promotional mechanisms such as viral marketing, user generated content, or ambient media. For example, chalk and hydro-water clean stencils on pavements could be used for great effect. But in Asian cultures, or if Arabic or religious symbols are incorporated in the brand design, then this could rule these options out if the logo appeared as they logos beneath the feet of people would be seen as being religiously disrespectful. Looking forward, halal brands have to be designed in a robust and unrestrictive way expecting that the brand will be carried and appear anywhere irrespective as to whether this is under the control of the organisation or not. Once a brand is created, it is owned collaboratively by anyone who chooses to consume it. Whilst Muslims and Islam may exact extra rules and obligations from the faithful, adherents have to be mindful that they will not have complete control on religious symbols. Therefore, that which is sacred should be reserved for situations, people and places where everyone involved shares similar ideals and codes of conduct. This is to minimise potentially distracting instances where misuse of the brand by whoever leads to the disrespect of Islam.

The challenges in creating halal brands

Brand theory puts forward the proposition that a brand can be separated from the product and service in that name, personality, identity, relationship, etc., can be created separately from the offering. In doing so, this expands the collective meaning, purpose and consumption of the tangible and intangible entity. For example, following basic Pavlovian and inductive principles, irreverence, seduction and desire can be the attributes of a brand, which are then grafted onto the functionality of a product or service. This results in the creation of an irreverent and seductive object of desire. Within the halal industry, it should be Islam, and more specifically halal, which assumes this position conceptually rather than any corporate or product brand. Therefore, this renders halal as the definitive factor instead of branding strategies which create something which is halal.

Whilst it can be argued that the same brand rationale is observed and practiced in the expanding halal sector, halal from its classical definition does not allow for this completely. What is halal at its apex is that which is pure, praiseworthy and of benefit. Therefore, for Muslims, it should be a given and present in all consumed commodities. An argument can only be made for the halal if the intention of those involved is sound and it guides consumers towards a way of life which is Islamic. If brand managers do not encourage and nurture what is halal, their brands may remain cultural products with a temporal halal status. The possible implication is that halal ingredient brands may have separate life cycles, which spawn the launch of new further ingredient brand creations. If commonplace, this defeats the purpose for which they were created.

More acutely, halal in business is often taken to mean what is permissible, and needs at every stage to be explicitly asserted rather than taken as a given. There are numerous optimistic and pessimistic inferences that can be gathered from this. In addition, these processes are having an impact on the meaning of halal, shifting it towards being a business commodity and away from a spiritual ethos. Secondly, the knock-on effect is that rather than a tool, halal could become a resource draining distraction. Thirdly, for short-term gains, the implications over the longer term are that halal may cease to deliver the same levels of intrinsic value, pushing the pendulum towards another strategic branding approach and new, more meaningful terms that resonate with consumers in the same way that halal used to.

Having raised these issues, it still remains contentious as to what makes something a halal brand? The following positions are reflective of differing perspectives:

- Positive assertion by the organisation, through the brand

- The nature of the product or service offering

- Country of origin

- Destination of the brand

- The faith of the corporate owner(s)

- Halal ingredient certification

- The share of Muslim- and Muslim/Islam-friendly consumer base

- The share of Muslim employees

- Positive citation of Muslim-friendly consumer and employee policies/practices

- Islamic or Islam-inspired symbolism and messages

As Muslim consumer behaviour and corporate practices are reframing the halal, the challenge faced by marketers from an academic, Islamic and ethical perspective is to identify, understand and respond to this phenomenon.

Much has been written about the “Holy Grail” of branding and the iconic status of brands in the modern world. Within the language used lies the allusion that powerful brands are western-centric and marbled with Christian symbolism and underpinnings. More recently, terms like “Avatars” open up thinking towards other religious belief systems and eastern perspectives. However, a key question remains as to whether these concepts can be applied to, or embrace the rise of Islamic marketing and Muslim consumer behaviour?

It can be taken from these observations that the first challenge, when creating halal brands, is that many of the terms and concepts which exist, that are used and resonate in the psyche of individuals are absent of overt Islamic terminology and concepts. This may in fact limit development. It is also worth considering whether this means halal brands have to be created within existing terms and concepts or whether a leap of faith should be taken to develop new Muslim-centric terms and concepts, which then necessitate that the marketplace has to be educated as to what they mean, and where the differences lie.

The phenomenon of brand worship is a desirable and necessary trait but at the very least is perhaps unavoidable amongst the most engaged consumers. Therefore, there are two key challenges that halal brands face. Firstly, the process of creation of a compelling halal brand should be the same as for any other brand but the intention of the brand creator has to be in line with Islamic principles. That means that having a brand that is designed not to contravene Islamic design ethics and symbolism is not enough; the intentions of the designer also have to be correct. Secondly, how the brand is promoted and communicated requires care and attention. God consciousness is something that should be encouraged by a halal brand but in the process, if this results in slavish reverence of the brand in question, then this will impact on the credibility of the halal brand itself. It is envisaged that these two points are in fact extremely difficult to manage – because a less than compelling brand will be ignored and will not only fail, but will also fail in encouraging the greater good, which is to engage in more Islamic fundamentals.

To further complicate matters, consumers are likely to have multiple and changing perspectives, which differ between brands; what works for one brand may not work for another.

The commoditisation of halal

Globalisation is driving increased sharing of practices and in tandem with these, three phenomena have emerged:

- A call and desire for clear re-classifications of products and services with halal monikers.

- A movement towards using the term halal within branding more frequently.

- Using the term halal as means by which economic gains can be achieved.

Halal certification has been used as a quasi co-brand

(e.g. Halal Insurance), ingredient brand, and brand extension. Also, it is apparent to a Muslim consumer that the HSBC Amanah Finance product, for example, is one which professes to be halal through its name. Amanah is an Arabic word, held to be of religious significance. In its general sense amanah means ‘trust’; however it also carries the sentiment of that trust being a divine privilege and therefore worthy of serious consideration. It follows that Muslims will only tend to use this word when they are engaged in something that is deemed halal. It is perhaps for these reasons that HSBC demonstrates an understanding of the Muslim psyche. In avoiding using the term halal, they have circumvented the potential for greater consumer scrutiny due to the significance and reverence attached to the word halal. However, this manoeuvring is perhaps only of cosmetic worth as Muslims understand that Amanah Finance still tacitly and explicitly markets itself as halal. Therefore, this is more perhaps an issue of semantics, comparable with the classification of other commodities. For example, whether a beverage is known as a “drink”, “juice” subsequently professes to be “healthy”.

Within Muslim countries, and especially those which have Arabic as their mother tongue, many products have previously taken their halal status as a given. However, many offerings now seek to brand themselves as halal, even within Arab speaking and Muslim nations. This is especially in cases where products are viewed as being foreign, or potentially contentious. For example, it may be more crucial to brand Han originating Chinese food (largely hailing from a non-Muslim majority) as halal in comparison to popular dishes native to Chinese Muslim tribes and Muslim countries. Due to the concept of avoidance of doubt, halal branding is in some way differentiated from other ingredient brands, such as “Fair Trade” or “sugar free”, and is more comparable to “suitable for vegetarians” where consumers have indelible laws of guidance. Therefore, halal often represents something of a hygiene factor and thus presents itself as a potential deal breaker if absent.

A point of interest lies in the case of MacDonald’s. Whilst MacDonald’s offers halal meat in Pakistan (a Muslim country), they have been less keen to overtly brand it as such in neighbouring India, despite it having larger numbers of Muslims. The reason is that there have been distinct cases where the Indian Hindu consumer majority have boycotted halal restaurants for political purposes. This appears to be less of a concern outside of India however as Hindus have expressed less vociferous opinions and are more likely to consume halal MacDonald’s freely within Muslim countries. The MacDonald’s case further supports the position that halal is viewed by Muslims and non-Muslims alike as being more than just an ingredient brand. Instead, its sublime symbolism is powerful in having deep structured interpretations. However, it does demonstrate the fact that consumers’ interpretations of brand messages are situation-specific. With this in mind, it may well be the case that organisations choosing to use the term halal will also have to consider much wider societal implications.

The halal consumer paradigm – pre consumption decision making

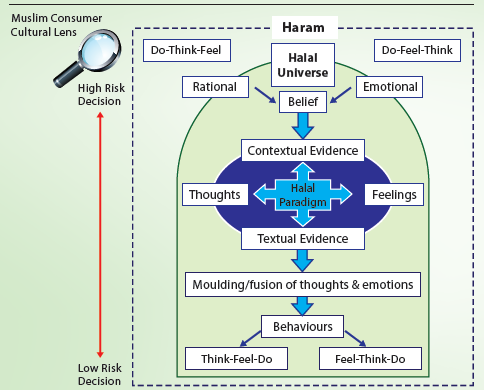

On another level, Muslims can be seen to select brands in a different way, which is governed by their interpretation as to what is halal. However, Muslim consumer behaviour and corporate practices point towards perspectives which are reframing the halal. Figure 2 presents the halal paradigm as demonstrating an area where cognitive (thinking), affective (feeling) and conative (doing) decision-making patterns are affected by risk minimisation. These are related to a Muslim consumer cultural lens and their interpretations of Islam. The hal paradigm is a nub where the perceived importance of halal is brought into the Muslim consciousness. This is a dynamic and cyclical process whose final verdict is finite and perishable due to hyper-sensitivity and environmental factors influencing Muslim perceptions of what is halal.

Marketing halal to Muslims

Zain Abdullah cites predictions of Muslims becoming a significant religious group in America.1 Within this, African Americans will make up the majority. However despite this conspicuous presence, Abdullah asserts that:

| Key terms:Moulding & fusion of thoughts and emotions – Halal heuristic hybrid-deconstruction approach. Collective individualism drives value-based judgements, derived from a laddering process as a result of a synthesised hierarchy and reflective of a self-defined decision tree. The concept of joining together, fusing and moulding is used in an Islamic context to describe the correct approach of Muslim belief and practice.Think-feel-do – Halal value-chain approach. Every stage and component is scrutinised rationally, according to their functional and materialistic elements, which necessitate textual justification.Feel-think-do – Halal cultural artefact approach. The resulting feelings, emotions and behavioural traits of collective consumerism ratify the validity of an approach.Observations and findings suggest that halal ingredient branding and overtly branded Islamic products, such as finance, tend towards brand messaging which evokes think-feel-do. Therefore, it is suggested that there remains an alternative, currently under-used approach, which requires further consideration as to how more overt emotional messages can be transmitted.Figure 2: The Muslim Consumer Lens |

“the orientalist stereotypes many westerners consume about Islam, prevent them from understanding the complex ways these Muslims negotiate their religious, racial, and ethnic identities.”

Abdullah states that Muslims define their respective identities through a process of boundary shifting which “does not only include a dichotomy between inclusion and exclusion, but refers to those situations where people negotiate multiple belongings or hybrid identities. This means individuals often navigate their personalities in ways that cause two, three or more identity markers to overlap. In other instances, they may revert to a single identity.”

These findings suggest that much work still needs to be done by marketers in order to enter the psyche of Muslim minds. On one side the strength of Islam lies in its adherence to a framework, which galvanises followers across the globe, under Arabic as the lingua franca. However, Muslims are still free to hold onto their respective, linguistic, ethnic and cultural identities. Building upon the findings of Abdullah, it is suggested that halal branding and marketing could be served well by looking for linkages within existing practices. With census figures indicating that Muslims especially have a large younger population, future activities will need cutting-edge approaches to gain credibility, which cannot be achieved by traditional interpretations of religion. As a pre-cursor, hip- hop music and urban fashion labels have also enjoyed global success through fusing Islamic symbolism into their mainstream product offerings. If halal is to make further inroads, it too should seek associations with partners, which do not just focus on the materialistic.

A study conducted by Allam Ahmed on marketing halal meat in the UK finds that all respondents stated that the authenticity of the meat being halal was the most important factor in purchasing the meat. Whilst supermarkets stocking halal lines are more capable of providing authentic information than some local butchers, Ahmed finds that Muslim consumers still prefer their local butchers. He asserts that:

“This result could be seen as contradictory, because 94 per cent of respondents thought supermarkets were more hygienic in comparison to only 6 per cent who thought local butchers were… Further questions are raised by the fact that 90 per cent of respondents think that supermarkets sell better quality meat.”

His suggestions are that trust communicated through cultural and long-term human interactions are of more importance to Muslim consumers in these instances. Following this, Ahmed also finds that 84 percent of Muslim respondents in fact did not ask their local halal butchers where the meat came from. The significant factor here seems to be in identifying whether the butcher is an observant and practicing Muslim. Therefore, if supermarket chains are to win the hearts, minds and purse strings of Muslim consumers, a greater reliance needs to be placed on supporting marketing activities with credible individuals who readily interact with consumers.

Current approaches have spawned fast food chains such as MacDonald’s, KFC, Dominos, and Subway who adapt some of their restaurant chains, even in the UK, by offering halal lines. The industry magazine, The Grocer, in 2007, stated that the halal food market in the UK alone is worth £700 million with Tesco looking to bring £148 million of Malaysian halal products to the UK over the next five years.2

Environmental factors are also points of consideration for Muslims. Whether the restaurant or supermarket also serves non-halal items are potential barriers present to both consumers and providers. Having stated this, there appear to be differing opinions and consumer practices. Some Muslims are happy to eat halal food as they see it in a restaurant which serves alcohol and pork in the same way that they are happy to buy halal food from a major supermarket chain. Retailers are likely to experience fewer barriers as food is pre-packed and prepared largely off-site. They are also more easily able to place a distance between contentious products in their stores. However, a point worthy of mention is that Muslims who eat halal food do not necessarily abstain from drinking alcohol.

In serving grateful Muslim audiences, mainstream corporations have received a mixed reception, with some concerned by the risk of over-exploitation, which in turn raises ethical issues. Muslims view health as having a strong spiritual element, encompassing elements of fatalism. Therefore, once something is been deemed halal, it is not a question of whether it can be consumed or not but rather the quantity. Furthermore, consumers in developing nations and economic migrants residing in developed nations could be seen as being more junior members of a global community due to their recent ascendency towards increased mass consumerism. Ahmed asserts that Muslims may be more willing to accept products and services of lower standards and quality. Federick Palumbo and Paul Herbig state that “Minorities are also known to be less cynical about advertising messages because they are actually seeking out information about the product: information that the general public may take for granted.” Within these, the hand of exploitation presents a clear and present danger. However, Leah Rickard suggests that minority groups have a tendency towards purchasing more branded products and those of quality.3 Therefore, there appears to be a gap in delivery typified by what Muslim consumers have to settle for and what they actually want.

The food and drink market research firm, Mintel Oxygen, values the UK Muslim population as having a combined spending power of £20.5 billion.4 The Grocer reports, once again in 2007, of Muslims’ concerns at some halal foods not complying with correct preparation procedures, resulting in the boycott of these products and organisations.5 However, there still remains little indication as to whether these concerns stretch any further than simple materialistic interpretations surrounding the absence of haram ingredients or correct slaughter procedures. The article suggests that once these basic concerns have been addressed, Muslim consumers will focus their attentions on the more implicit and aspirational elements of halal, which will necessitate that the more human elements of branding play more of a role when catering for these desires. Mintel Oxygen, in their future and forecast section, cite branding as being critical factor which will allow for sector expansion.

In the interests of maintaining quality and control there have emerged halal brands carrying additional certification and authenticity from Islamic councils. Their remit nevertheless would appear to be restrictive in that they simply view products and services according to their ingredients. Collectively if unaddressed, Islamic councils, manufacturers and consumers risk the devaluation of halal as a strategic brand element in their acceptance of these practices.

An approach which could serve as an interesting bridge and framework for understanding the Muslim gastronomic psyche may be taken from the eminent philosopher, Pierre Bourdieu.6 Bourdieu suggests that social class and cultural drivers play a major role in taste rather than just income as hypothesised by economic demand theory. This position has been examined in several studies that collectively assert that culture plays a key role within food consumption and associated brand activities.7 In this, a more strategic and consumer- centred approach could be examined over the long term which blends the rich tapestry and legacy of culture with modern marketing trends.

However, for small businesses, it is unlikely that they will be able to make significant in-roads within seemingly cautious, parochial and at times tribal Muslim populations. The likelihood is that real in-roads will be made once a larger supermarket chain decides to throw its weight behind this approach, with superior marketing budgets and distribution networks. In this instance, it is also likely that yet another halal authority will be established with compatible values in order to gain necessary credibility.

If this does happen then the battle for halal status and credibility will inevitably be pulled towards a battle of the brands and marketing campaigns. In the advent of such an occurrence, there lie concerns. The scales of religious sensibility have the potential to be tipped towards placing corporations in the driving seat through heavy-weight marketing and an increased commoditisation of religion. Therefore, the future points to one where ownership of what is halal will be shifted towards interpretations looking to embed strategic brand theory. Here, there is a distinct possibility that halal will culminate in moving beyond being something of just Islamic significance. The risk associated with this is that Muslim consumers may be irreversibly relinquishing some of their control over definitions of halal into the hands of marketers. This in itself may provide the oxygen for views espousing an apocalyptic degradation of religion, in need of a remedy through increased extremism. This is comparably seen when observing the views and actions of the most extreme single-issue politics protestors. Within their commercialisation, Fair Trade goods have encountered similar challenges as the tide of opinion turns whereby they have been perceived significantly to add both a premium and competitive advantage to commodities for commercial gains.

Scope and scalability of the halal paradigm

Moving forward, a key area for discussion is what emotional elements are acceptable within the halal paradigm, how can they be evoked, and to what degree can they be deployed. Few halal brands appear yet to be able to satiate both the rational and the emotional beyond mere functional and materialistic interpretations. For example, emotions such as seduction and humour appear to be contentious topics when discussed in connection with Islamic brands. If overtly Islamic and halal brands are to take centre stage within the psyche of the Muslim consumer and beyond to a wider global audience, they cannot be neutered and sanitised. However, this is not to say that they have to sell their souls in the process. The halal paradigm can be applied in a wider context to those with faith and indelible beliefs, which prevent consumers from the conscious consumption of certain commodities. To this end, the same principle can hold for practising Christians, Jews, vegetarians and other single-issue groups, amongst others. It is also argued that this perspective is indicative of a new-age marketing approach, which concedes that consumers cannot be coerced with either transactional or relationship marketing methods without conceding that there are boundaries and limitations defined by the consumer.

According to Islamic principles, halal is the norm and haram is the exception. Whilst this construct offers a general principle within the halal paradigm of consumption attached to consumerism, an argument is put forward which asserts that this is increasingly being reversed due to a trait of risk aversion, which is attached to fear and suspicion. The drivers for this are a type of hyper-sensitivity and hyper-interactivity which are encouraged by:

- The commodification of entities through branding and national boundary ownership

- Hyper-information exchanges and education, which bring constituent components under scrutiny

- The mass manufacture of bulk commodities

- Technological and genetic engineering advancements

- Challenges by single-issue politics and anti-branding movements

The BBC online reported that banks offering such products as Islamic finance -which by its very nature carries halal status- have attracted British non-Muslims. The article further states that “up to 25% of Islamic accounts are opened by non-Muslims.” In Malaysia.8 It could be argued that this is surprising considering that these financial products are non-interest bearing, and whilst they may be considered a necessity to someone following the Muslim faith, begs the question why others would want to adopt them? This is especially because economic gains seem to take a back seat. In response, non-Muslim consumers, questioned for the article, equated Islamic finance with ethical living. They were attracted by the prospect of their money not being invested by the bank in such things as pornography and arms. In addition, they also supported the Islamic position of wealth being only generated through legitimate trade and investment in assets, and not by making money from money.

One academic study investigated the factors affecting Muslim and non-Muslim patronage of Islamic banks in Malaysia.9 Their findings show that:

“about 39 per cent of the Muslim respondents believe that religion is the only reason why people patronize the Islamic bank, and, surprisingly, the percentage is much lower for non-Muslims. More than half of both

respondent groups have indicated the possibility of establishing a relationship with the Islamic bank if they have a complete understanding about the operations of an Islamic bank.”

Following these findings, they conclude that an Islamic bank “should not over emphasize, and rely on, the religion factor as a strategy in its effort to attract more customers.” In addition, they assert that dress code and customer relations techniques are also areas which should be emphasised.

Following Mokhthar Metwally’s assertions concerning the use of Islamic principles and their subsequent economic implications10, it would follow that halal- centric brand equity calculations should also be subject to review. Ying Fan states that conventional brand equity models define their value through economic performance in financial terms.11 However, he asserts that these models have deficiencies in not assessing ethical measures. Therefore, in the case of halal where a strong code of ethics exists, such appraisals will become even more crucial. In the shadow of the current economic climate highlighting mismanagement in finances and the recent furore over expenses claims made by UK members of parliament, it is likely that the wider population will increase in their desire for more ethically based products.

Conclusion

The investigation of halal and, more specifically, those aspects pertaining to branding and business are still in their infancy. However, the wider implications associated with halal and its potential to permeate other disciplines should not be overlooked or remain restrictive in their approach. Halal is a paradigm which necessitates an appreciation of:

- Multiple, situation-specific, cultural traits

- Figurative, esoteric and symbolic states

- Strong ethical standpoints

- Relationships away from just materialistic and mechanical process-driven thought

- Strategic management practices

This pushes thought towards comparisons with more emotionally driven and high-involvement luxury purchases. Leah Rickard suggests that marketers should consider trends where minority groups have a tendency towards purchasing more branded products and those of quality. This would be in keeping with the postulation that minorities are attempting to build up equity and acceptance through overtly branded and prestigious artefacts. Through these trends, brands and marketers have the potential to extend their portfolios and equity. These can be further strengthened through embedding more communication which seeks to mesh with the psyche of diverse multi-cultural audiences. Notably because of halal’s religious roots, such traits would also extend to FMCG goods despite these items being thought of as being traditionally low-involvement and more rational than emotional purchases.

For the reasons stated, it is unlikely that all Muslims will ever be able to agree on one approach to “Halal Branding.” Debates continue to run over matters such as the stunning of animals prior to slaughter, the use of alcohol in fragrances, and even philosophical arguments against labelling alcohol-free beers. The position taken here is that these consultation processes and such opinion sharing should be welcomed but it should also be assumed that they will carry on indefinitely. Therefore, stakeholders should be encouraged to consider that seeking complete control and consensus are divisive and energy sapping. So, whilst in theory it is possible to discern what is halal and what is not, when something seeks to carry branding and certification, this becomes more difficult to evaluate.

The following are some suggestions of areas that could be explored in the future:

- Further discussions surrounding the unification of certification practices and certifiers.

- The role of country of origin and nation branding in communicating brand

- Think tanks, comprising of religious scholars and brand experts, across schools of thought and market

- Formal consumer-led watchdog groups, using social

- Expansion and separation of halal classifications. These could be used to differentiate between products, which are technically halal and those that have additional benefits associated with health and nutritional values. So for example, some products could achieve halal status, whilst others achieve a label classifying them as being “Suitable for Muslims.” In addition, scaling systems could be provided which indicate how much consumption is recommended.

- A labelling system and marketing communications approach, which allow for ease of understanding by non-Muslims. Beyond this, it has the potential to evoke similar positive traits. After all, Islamic thought would argue that halal resonates with all human spirits, regardless of their current belief systems as all are created with the potential to understand, by Allah (swt). However, there still appears to be a paucity of understanding by the wider community, as to what halal covers other than “meat and money.”

- Specific academic courses which focus on “Muslim Consumer Behaviour” and “Islamic Branding”.

- Further research into how brand theories can be used in an Islamic context, allowing for further application of cognitive behavioural psychology to elicit the more emotional attributes of a brand without going against the ideals of Islam. Following this, attempts could be made to launch emotive premium high-end luxury

Finally, what Islam states within its texts and what is practiced by Muslims and non-Muslims offer some form of overlap but unless each are understood both in isolation and in their dependency, there will remain gaps. However, what is not being suggested here is that full mastery over this field will ever grant complete control over what is halal. Rather, halal will provide more gains and will become less of an enigma.