Introduction

Islamic microfinance is a new frontier that many observers, academic and practitioner alike, are keen to explore. The failure of many Islamic banks to reach out to the poor parallels the inability of commercial banks to provide necessary capital to the less fortunate segments of society. Although it is not fair to assign the Islamic bank with social objectives, historical fact and strong association between the establishment of Mit Ghamr, arguably the first Islamic financial intermediary, and the emergence of Islamic banking in the 1970s is undeniable.

The conventional microfinance sector has evolved from largely subsidized rural lending programmes into a sustainable industry, which attracts commercial banks and fund managers. These institutions develop customized products, either directly targeting the poor and microenterprises or indirectly through capital investments into microfinance institutions (MFIs). The focus of MFIs has also shifted from providing only credit to microenterprises to offering an array of financial products that serve the growing needs of the poor, such as savings and insurance. The product offering is slowly moving away from just microcredit to a range of microfinancial services, and in recent years, increasingly towards achieving a broader objective of financial inclusion (Ledgerwood et al., 2012).

There has also been a surge in academic papers discussing microfinance from various perspectives since the early 1990s. In addition to increasing popularity and the alleged success of many MFIs, the availability of data in recent decades has been the main reason for this surge (Brau and Woller, 2004). Recent studies take stock of research in microfinance in the last two or three decades, by among others, Armendariz and Labie (2011), Banerjee (2013) and Cull et al. (2013).

Against this backdrop, Islamic microfinance is quietly evolving from an experiment into a niche industry in some Muslim countries, especially Indonesia, Bangladesh, Sudan, Lebanon, Pakistan and Yemen. While this development is encouraging, increasing interest in the microfinance sector from large scale institutions, rising competition and massive commercialization, will require Islamic MFIs (IMFI) to shift gear and assess existing strategies. Current market conditions require more than just a good mix of financing models, but also innovative products, sustainable funding strategies, effective use of micro-banking technology, advocating an enabling regulatory framework, and above all an ability to answer the main calling for Islamic finance, which is creating an impact on the living standards of over 500 million Muslims who are still in poverty.

Development of Conventional Microfinance

There are few economic models that explain the development of the microfinance sector. Some models high- light the role of enhancing the capacity of endogenous factors of production such as human capital or labor; others concentrate on increasing exogenous factors such as financial capital of the poor and microenterprises. In line with this, the poverty trap argument has also been used and provides a stronger reason for improving exogenous factors or financial capacity in microfinance development. This is for instance proposed by Sachs et al. (2004), who argue that lack of domestic savings and rapid population growth has intensified the poverty traps with the deterioration of capital and productivity leading to poor economic growth and advancement.

Table 1: Microfinance and Islamic Microfinance

Microfinance

Microfinance is defined as “the collection of banking practices built around providing small loans (typically without collateral) and accepting tiny savings deposits.” (Armendariz and Morduch, 2005). Hence, microfinance is a set of financial services designed for poor households who are excluded from the traditional banking system due to the lack of collateral. Till now, there is no striking evidence of an efficient micro-lending mechanism that ensure high repayment rates, lower transaction costs (including cost of default), maximum pay off and positive macroeconomic and social impacts. Despite this fact, the global microfinance industry has shown during the last decade remarkable growth of around 20%, coming mainly from South and East Asia, and Africa. However, the current outreach of microfinance remains insufficient, especially in the rural areas of developing countries. In OIC member countries, microfinance is predominantly urban, except in Indonesia.

Islamic Microfinance

Achieving social justice by providing equal opportunities to individuals within a society is an important objective of economic development from an Islamic perspective. (Chapra, 1983). Achieving this objective guarantees the maximum level of financial inclusion to all segments of society. Financial inclusion of low-income individuals in OIC countries will benefit from the development of Islamic microfinance services. Islamic microfinance can be defined as the provision of microfinance services in compliance with Islamic rules, and coherence with its moral values of social solidarity and caring for the less fortunate. Islamic microfinance is the synthesis of two rapidly growing industries: Microfinance and Islamic finance. Although, it is still a niche market in OIC countries, Islamic microfinance has huge growth potential and is considered as “the key to providing financial access to millions of Muslim poor who currently reject microfinance products that do not comply with Islamic law.” (Karim et al 2008).

Another explanation is market failure theory, which suggests that the poor have been left out from economic growth and development due to the failure of commercial banks to provide them with capital (Armendariz and Morduch, 2005). They argue that market failure theory is the main driver in the development of microfinance, i.e. the failure of banks to reach out to poor families or microenterprises that are in need of capital. In turn, the authors suggest that market failure is due to asymmetric information and agency problems. The success of BancoSol, Bank Rakyat Indonesia Unit Desa, Accion, Sewa and many other pioneers in microfinance, complement the poverty reduction programs of respective governments in Bangladesh, Bolivia, Indonesia and India. Perhaps the preeminent example of this argument is Muhammad Yu- nus and Grameen Bank from Bangladesh. So successful is Grameen Bank that today it is almost impossible to dissociate microfinance from Grameen or Muhammad Yunus. Many subsequent efforts to establish MFIs rep- licate the lending model introduced by Grameen Bank (Hermes and Lensink, 2007, Johnston and Morduch, 2008, Cull et al., 2009).

There are however observers who retrace the history of microfinance or microcredit long before the emergence of Grameen Bank, or BancoSol of Bolivia or Bank Rakyat Indonesia. For instance, the farmers credit union in Ireland (Hollis and Sweetman, 1998), rural credit cooperatives in Germany (Guinnane, 2011), and some similar movements in countries like Indonesia, Philippines and Thailand (Adams and Fitchett, 1992). In the more recent period, the experience of the Indian sub-continent and Latin America also caught the attention of researchers, such as Sundaresan (2008), who attributed the development of microfinance between 1950-1980s to Accion and Sewa Bank in Latin America and India respectively.

The basic premise of microfinance is to enable the poor to emerge from poverty and at the same time deliver sustainable returns for the providers of microloans and micro financial services. This is often called double bottom line, i.e. social impact of poverty reduction and financial sustainability of the MFI. In the process, it is hoped that this movement will enable a less developed country to develop a mature and inclusive financial sys- tem. However, the balancing act of attaining these two objectives, often conflicting by nature, is not easy. Putting more emphasis on the social dimension may create ad- verse or unwanted consequences such as dependence on subsidies, lower outreach or lack of sustainability; likewise, an emphasis on sustainability may divert attention on the poor to profitability of the MFI. The later strategy is criticized as being a mere “schism” (Morduch, 2000). The author puts forward critical reviews on the proposition that the banking approach to microfinance is said to be more efficient in poverty reduction. He argues that the proposition (also known as the win-win proposition) is neither supported by logic nor empirical evidence; in fact it has created a dichotomy or unnecessary trade-off in the microfinance movement between sustainability of the MFI and social impact on the poor.

Today, conventional microfinance has evolved from sole offering of credit to an array of financial services, or a change from microcredit to microfinance (Matin et al., 2002), and lately a shift in institutional focus from subsidy dependence to sustainable profit-seeking (Cull et al., 2009). In addition, microfinance is also being mandated to increase the number of people that have interaction with financial institutions, i.e. to increase the number of people with bank accounts. The financial inclusion movement is led by the World Bank. In a new book, Banking the World (Cull et al., 2013), this narrative is highlighted and illustrated by some empirical evidence from all over the world. The main argument in this book is that microfinance would be able to convert the number of unbanked population, currently about half of the world population, by at least 50% over the next 20 years. Clearly this is not an easy task, as many MFIs may adopt commercial objectives, moving further away from meeting the more difficult social objective of poverty alleviation.

The Main Proposition of Islamic Microfinance

IMFIs can be involved in 4 main types of products/services:

- Providing Access to Finance Products

These can be trade based/micro-credit financing such as Murabaha, istisna’, salam, or equity-based/micro equity financing in the form of mudaraba, musharaka, and ijara.

- Providing Asset Building Products

These are typically saving accounts, current accounts and investment deposits.

- Providing Safety Net Products

For instance, microtakaful.

- Providing Social Services

Charity-based contracts such as qard hasan, zakat funds, sadaqa, and dedicated waqf.

In mudaraba based contracts, the risk assumed by the IMFI is presumed to be high due to moral hazard. Under such an arrangement, profits are pre-determined and shared on the basis of agreed ratios, while the IMFI assumes any loss. The latter offers the money needed for micro-projects, and the micro-entrepreneur contributes by his time and effort. Control and management are the responsibility of the micro-entrepreneur, while the IMFI can only supervise and monitor. In musharaka based contracts the IMFI and the entrepreneur jointly contribute to the financing and management of the project. The profits are shared according to a pre-determined ratio, and losses are jointly endured by both of them according to their capital contribution. Therefore, the IMFIs have to monitor the effective undertaking of the micro-projects and ensure timely repayment. Repayment can be made differently using specific monitoring systems depending on the Islamic microfinance model (For in- stance, incremental repayment).

In practice, micro equity financing modes are rarely used by IMFIs with preference tending towards micro credit modes. This is due to information asymmetry problems, and more particularly, moral hazard. Moral hazard problem arises when the borrower has an incentive to undertake lower effort which reduces the probability of the micro-project’s success. According to El-Zoghbi,

- and P. Serres. (2012), 74.8% of active financing clients in the 19 considered OIC countries, are financed through Murabaha, while Qard Hasan finances 21.6% of the clients. musharaka, mudaraba and salam are rarely used representing less than 1%. This is unfortunate, as musharaka have so much to offer Islamic microfinance. For instance, musharaka provides adequate commercial incentives for MFIs and banks (Akhtar, 1997), protects the borrowers from inflation pressure on their assets or investment (Abdalla, 1999), and it could also provide a basis for sustainable form of financing for the economy at large (Harper, 1994).

The moral hazard problem is common in charity based contracts as well as micro-equity modes of financing. In the deployment of qard hasan, borrowers have to repay the exact loan amount with no extra fees. By spending their loan for consumption or other purposes, and not for income-generating activities, borrowers may find themselves unable or unwilling to pay back the loan when due. In Iran, for instance, from more than 1200 qard hasan fund institutions repayment rate was only 60% (Kazem, 2007). Qard hasan beneficiaries believed that the money offered to them was a sort of charity, to be forgiven if there was a default and hence no punishment (Karim,Tarazi and Reille, 2008). Similar to conventional microfinance, social capital can serve as the basic collateral. Usually, peer monitoring and pre-selection of the clients, based on their reputation, contribute to lessen the moral hazard problems that lenders face.

In recent years, there have been several attempts that explore the application and applicability of Islamic co-operative schemes targeting the poor (Ebrahim, 2009). There have also been experiments on the repayment behaviour of Islamic microfinance borrowers as tested by El-Komi and Croson (2013), who use experimental economics to confirm the feasibility of Islamic microfinance in the context of information asymmetry and verification. Both studies suggest that Islamic micro financial services are robust and in certain cases more efficient than other types of financial services targeting the poor. El-Komi and Croson (2013) show that borrowers using mudaraba and musharaka contracts are more likely to comply with their terms of loans than those under interest based loan arrangements. It is suggested that Islamic microfinance is more efficient where the information asymmetry assumption holds. Similarly, Smolo and Ismail (2011) find that Islamic microfinance would be able to resort to more sources of funding than their conventional counterparts, as well as use a variety of products to suit different types of clients.

Islamic Microfinance: Where do we Stand?

Islamic microfinance has enjoyed relatively strong growth in the past ten years, coinciding with the growth of the Islamic finance. Unlike Islamic finance, which is driven mainly by such financial centers as Dubai, Kuala Lumpur and London, Islamic microfinance emerged in developing countries. It flourishes in the developing economies of South Asia (Pakistan, Bangladesh), South East Asia (Indonesia, Malaysia) and Sub-Saharan Africa (Sudan). Among the front runners are Islami Bank Bang- ladesh, Akhuwat in Pakistan, Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia and Agricultural Bank of Sudan. Islamic microfinance institutions can be found in more than 15 countries across Asia (Afghanistan, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Malaysia), Middle East and North Africa (Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Sudan, and Yemen), Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan) and Eastern Europe (Bosnia Herzegovina, Kosovo).Table 1 provides a partial list of Islamic MFIs.

However, the overall supply of Islamic microfinance products is small relatively to the conventional microfinance sector. Indeed, Islamic microfinance presents less than 1% of global microfinance programs . The estimated total number of poor clients using Shari’a-compliant products is about 1.28 million, while there are only 255 providers of Shari’a-compatible microfinance products and services worldwide. About 64 % of these providers are concentrated in East Asia and Pacific and 28 % concentrated in the Middle East and North Africa.

Table 2: Sample of IMFIs

| No | Country/Islamic MFIs | Legal Status | Gross Financing Portfolio (US$) | Number of clients |

| Afghanistan | ||||

| 1 | IIFC – Islamic Investment and Finance Cooperatives* | Cooperative | 22,900,000 | 22,155 |

| 2 | Mutahid DFI* | NBFI | 888,609.9 | 3,194 |

| 3 | FINCA – Afghanistan* | Village bank | 9,500,000 | 19,305 |

| Bahrain | ||||

| 4 | Family Bank*** | Bank | 1,094,821 | 344 |

| Bangladesh | ||||

| 5 | Muslim Aid* | NGO | 6,896,644 | 49,192 |

| 6 | Islamic Relief Bangladesh*** | NGO | ||

| 7 | Islami Bank Bangladesh – RDS*** | Bank | – | 836,227 |

| Bosnia Herzegovina | ||||

| 8 | Prva Islamska Mikrokreditna*** | NGO | (€)776,375 | 1,321 |

| Egypt | ||||

| 9 | Bab Rizq Jameel** | NGO | 1,943,510 | 8,577 |

| Indonesia | ||||

| 10 | BPRS Harta Insan Karimah | Rural Bank | 26,832 | – |

| 11 | BMT Ventura (137 BMTs) | Cooperative | 4,734,410 | 14,316 |

| Iraq | ||||

| 12 | Al-Takadum | NGO | 12,010,759 | 12,023 |

| 13 | Al-Thiqa | NGO | 33,972,397 | 15,572 |

| Jordan | ||||

| 14 | FINCA – Jordan | Village Bank | 7,599,086 | 15,416 |

| 15 | KosovoSTART Microfinance* | NBFI | 2,733,593 | 3,000 |

| Lebanon | ||||

| 16 | Al-Majmoua | NGO | 30,773,890 | 36,726 |

| Malaysia | ||||

| 17 | Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia* | NGO | 383,101,089 | – |

| Pakistan | ||||

| 18 | Akhuwat* | NGO | 16,088,012 | 180,880 |

| 19 | Wasil* | NGO | 1,087,899 | 4,537 |

| Saudi Arabia | ||||

| 20 | Jana** | 6,000,000 | 4,889 | |

| Sudan | ||||

| 21 | Family Bank | Bank | 63,056,518 | 58,909 |

| 22 | Pased | Bank | 1,291,425 | 6,006 |

| Syria | ||||

| 23 | Jabal al-Hoss | NGO | 1,118,960 | 1,128 |

| Yemen | ||||

| 24 | Al Amal Microfinance Bank | Bank | 7,523,945 | 32,215 |

| 25 | Abyan | NGO | 889,527 | 5,729 |

Source: Estimate from various sources, including MIX Market Database (2012 data)*, Sanabel Network (2010 data)** and individual MFIs annual reports (2012)***.

According to Karim, Tarazi and Reille (2008) 20% to 60% of the population in various Muslim countries displayed potential demand to access Islamic finance. In addition, 72% of people in Muslim countries do not use formal financial services. In terms of active financing clients, Bangladesh is ranked first with 445,153 clients followed by Sudan (2nd with 401,600 clients), Indonesia (3rd with 177,686 clients). However, Sudan has the highest growth since the number of active clients passed from 9,500 in 2007 to 400,000 in 2012. In terms of US$ outstanding, Indonesia is ranked first (above US$ 400 million) followed by Lebanon (US$ 135 million) and Bangladesh (US$ 90 million). In term of the number of clients having deposits in IMFIs, Indonesia is leading the OIC countries with 646,506 depositors followed by Afghanistan (70,047 depositors), Bangladesh (58,973), Sudan (25, 118) and Yemen (24,323) . As revealed by the study of El-Zoghbi, M. and P. Serres (2013) which covered 255 IMFIs in 19 OIC countries, the types of the Islamic microfinance providers are microfinance rural banks (77%), NGOs (10%), NBFIs (5%),Cooperatives (4%), and Commercial Banks (2%). The latter has the greatest share of clients (60%) while NGOs and micro finance rural banks have 18% and 16% of the total clients respectively.

The challenges facing Islamic MFIs are coming from various directions. They include intensifying competition from commercial Islamic banks and conventional banks or MFIs, tightening of the regulatory framework governing MFIs in many jurisdictions, securing sustainable funding as many donor funds or government subsidies are evaporating, as well as balancing a prevalent trade-off between poverty outreach and financial sustainability.

Competition is probably the main focus for many providers of Islamic microfinance, in addition to funding sustainability and balancing between the bottom lines or choosing the right lending models that are available. The challenging situation can be best explained by the state of competition in the sector, whereby up to five key providers can control between 70-80% of the market share. In Indonesia for instance, the microfinance sector belongs to the big players such Bank Rakyat Indonesia, Bank Mandiri, BTPN and few other commercial banks. The same is true with the dominance of BRAC, ASA and Grameen Bank in Bangladesh. Globally, multinational groups such as BRAC, FINCA or Accion operate locally in many countries with established lending models and products, as well as access to funding from international markets.

The following case studies of notable Islamic microfinance models are discussed.

- Akhuwat

Akhuwat is an NGO and a volunteer driven microfinance programme in Pakistan, in which funding sources are mobilized by volunteers from benevolent Muslim and social organizations. Since its establishment in 2001, Akhuwat has disbursed US$13 million and reached over 125,000 clients. What makes Akhuwat interesting is its method of disbursement. On any disbursement day, borrowers are invited to a mosque, or in a few instances to a church where borrowers are Christians, and all the eligible clients are handed over the loan while being witnessed by everybody else.

Akhuwat disburses qard hasan to individuals in a public space, which reinforces peer pressure and reduces moral hazard. While this is not specifically prescribed in Islamic teachings, the innovation is hitherto unique to Akhuwat. The method is indeed effective in reaching out to a large poor population, although the model relies heavily on voluntary donations for funding and volunteers for disbursement and client management.

For other institutions to replicate the Akhuwat model, it will require more than just the availability or willingness of many volunteers. Prevailing social trust and cohesion in the Pakistani society provide an impetus and enabling factor for the model to work and deliver fascinating re-sults. The Akhuwat model also depends on continuous support from thousands of individuals or institutional donors and contributors, which highlight the importance of an army of volunteers.

- Baitul Mal wat-Tamwil (BMT)

Baitul Mal wat-Tamwil (BMT) is a uniquely Indonesian model. BMT itself is an acronym of Arabic terms, which can be translated freely as fiscal and financial institution. BMT was initially a religious institution introduced by an Islamic organization in Indonesia to help facilitate business activities of its members. Since there was no specific regulation on MFIs during that period, BMT was formally registered as a cooperative. This created regulatory problems as cooperatives can only serve members. Most of the customers of BMTs did not want to be members, so they were being registered as applicants for membership (or expected member), which is permissible under the Act regulating cooperatives.

Despite this limitation, BMT has grown from a dozen branches in 1993 to more than 3,000 by the end of 2013. Similar to Akhuwat, some BMTs use qard hasan as their primary mode of financing, while many others are using commercial modes of financing such as murabaha. The BMT model is far from perfect, indicated by many failures over the years, and the quality of more than half of the existing 3,000 registered BMTs remains questionable. Low capital requirements and easy registration and licensing processes have attracted many individuals and foundations to establish BMT. However, with the new law on microfinance introduced in January 2013, the regulatory requirement and supervisory regime for Islamic microfinance is now much clearer and more stringent.

The main advantage of BMT is its ability to reach out to the very poor, due to its relatively small size and location within poor communities in rural areas or urban centres. Although the majority of BMTs are registered as cooperatives, they operate more like rural banks that can mobilize savings and extend loans. Few BMTs are also offering micro takaful to their customers, for instance BMT Sidogiri in East Java and BMT Tazkia in West Java.

- Banking Model – Family Bank, Bahrain

Family Bank is a new generation of Islamic commercial bank focusing exclusively on small and medium enterprises, and operates fully as a micro-lending bank. Family Bank was established in 2009 in a country with very few poor families – poverty incidence is only 2%, representing nearly 100,000 of the 6 million people in the Kingdom. As a commercial entity, the bank works with Grameen Trust as a strategic partner, especially for the poorer segment of the market. The Grameen program disburses retail loans of between US$100 to US$500, while the commercial micro loan is between US$500 and US$5,000.

Family Bank is not the only commercial micro-lending bank in the Muslim world. Similar institutions have recently sprang up in Indonesia (BRI Syariah), Bangladesh, Pakistan and perhaps much earlier in Sudan (Agricultural Bank). This is a relatively good start for the Islamic microfinance industry, especially in providing a platform for the seamless transition of entrepreneurs from being MFI clients to commercial bank customers.

However, the main challenge for some of these commercial Islamic banks is defining their market segment and making a profit. In the case of Family Bank, it is still making losses since its inception in 2009, while for BRI Syariah in Indonesia, the challenge is to stay true to its vision as an Islamic micro bank and not retail or consumer Islamic bank, as its financing portfolio currently suggests (70% retail, 25% SME/micro).

Funding Sustainability: What’s next for Islamic Microfinance?

As the sector grows and competition intensifies, securing funding for the rapidly increasing number of clients is among the key ingredients for future success and survival of IMFIs. While funding sources might not be limited, for now, selecting the one that suits internal strategy and a targeted group of beneficiaries are crucial.

Savings and deposits that are designed to mobilize funding from clients or other third parties remain important instruments for many MFIs. As of 2010, MIX Market recorded that deposits and savings account for nearly half (47.56 %) of the funding structure for most MFIs in the world. Debt and equity follow suit with 28.79 % and 18.29 % contribution to the total funds raised by MFIs. Another study finds that 65 % of these MFIs are relying on deposits; borrowing from international institutions come second and accounts for 27 %, shares or equity 20 %, and only 1.7 % based on bonds (long term debt). Deposits constitute 74 % of time de- posit, 26 % savings and negligible 0.1 % from checking account (Maisch, et.al. 2006).

For Islamic microfinance, Shari’a-compliant funding instruments are widely available and should provide alternatives for IMFIs. One potential instrument is sukuk, which in recent years have been considered as an at-tractive way to raise funds, but has yet to be launched in order to support the expansion of MFIs. The main obstacle in attempting to issue sukuk is a long and demanding process and procedure, despite obvious demand and the fact that many investors are already familiar with the sukuk structure. However, in the long run, this method should be considered a feasible and possibly the least costly mode of funding for microfinance.

The following methods should also be considered as alternatives.

- Social Business

The involvement of corporate entities and private companies in poverty alleviation became more prominent with the global recognition of Grameen Bank as champions of microcredit and the fight against poverty. Many corporations around the world wanted to associate themselves with Grameen for social and profit-making purposes. These ensuing joint ventures later on gave birth to the social business movement.

The model is defined as a self-sustaining company that sells goods or services and repays its owners for their investments, but whose primary purpose is to serve society and improve the lives of the poor. In this model, companies and Grameen typically establish an organization that produces special products to serve specific markets in Bangladesh or elsewhere. For instance, Grameen Danone provides affordable dairy products to the poor in Bangladesh. Groupe Danone is a French food- products multinational corporation.

The other notable organizations that are developing social enterprises include Abdul Latif Jameel of Saudi Arabia, which are establishing Bab Rizq Jameel that operate vocational training centres and MFIs in many parts of the Arab world, or BRAC in Bangladesh that has been using this model to develop its relief operations in the 1970s.

Many such corporations are increasingly aware of microfinance and its capability to deliver social impact to the poorest segment of society. This could be the main argument and selling point for providers to approach and launch social enterprises with these companies. The key to mobilizing funds in this model is delivery of convincing results from microfinance operations, which is supported by an excellent program and robust monitoring-evaluation systems.

- Investment Funds

A similar model to social business is social impact investment (or impact investment). In this model, fund managers or private equity firms create specific microfinance funds and then raise money from investors. The proceeds are then invested typically in baskets of MFIs in developing countries.. As most MFIs are operating with high margins, prolonged profitability, and high repayment rates, the funds are very attractive to many global investors.

According to MicroRate’s Annual Survey and Analysis of Microfinance Investment Vehicles 2011, the total as- sets of MFIs managed by these Microfinance Investment Vehicles (MIVs) have reached more than US$4.8 billion in 2010, with a growth rate of about 18 % per annum. Currently there are five fund managers that dominate this new market, namely Blue Orchard, responsibility, DWM, Triodos and ACCION. Shari’a-compliant investment funds are still at its infancy, but the prospect and demand are certainly there in the market.

In this ‘genre’, there are also companies that behave less like fund managers and more like real investors. In this model, organizations like Global Partnerships provide capital and funding to MFIs through equity participation and other long-term forms of investment. As at the end of 2012, Global Partnerships has invested US$44.4 million of its capital to about 35 MFIs across Latin America, with an outreach of nearly 110,000 clients.

This investment model has consequences to many Islamic microfinance operations. First, the funds only invest in MFIs that have some track record (outreach, profitability) and future income possibility, i.e. generating profit for a certain period of time. This may require a change in the microfinance programme management, mainly a shift from social orientation to profit (mission drift?). Second, and most importantly, it requires a major change in the capital and governance structure of MFIs. With the injection of new funds, investors may request rights of ownership or management change.

- P2P or Crowd Funding Model

Person-to-person, or peer-to-peer (P2P) loan was made popular by Kiva.org in 2005, as a way to facilitate individual lenders to support the poor with small but repeating loans. The simplicity of the online platform used by Kiva has attracted nearly one million individual lenders from many countries since its launch, and together they have provided small loans of about US$400 in 67 developing countries.

To do this, Kiva works with more than 184 field partners or MFIs. To become a partner, an existing MFI must have been in operation for 2-3 years, with a minimum active member base of 1,000, and preferably with a profile listing in the MIX Market database. For each field partner, Kiva will allocate credit lines from US$20,000 to US$2 million, depending on the partner’s due diligence status. Kiva also provides Islamic finance products through its field partner in Yemen, Al Amal Microfinance Bank. To date, the number of Islamic investments from Kiva is still relatively small compared to the overall investment or interest based loans.

An Islamic equivalent to Kiva is Wafaa (wafaalend.org) which was launched in Indonesia in 2008. It is currently based in London and provides financing to poor Muslim countries or Muslim communities in crisis-affected countries. To date, Wafaa has managed to finance 3,530 micro-entrepreneurs with projects worth US$12.2 million in about six countries. Microlenders have reached nearly 600 individuals.

Clearly Kiva and Wafaa are not the only initiatives to provide individuals an avenue to share their income with fellow human beings in other parts of the world. Some organizations have set up alternatives to Kiva, such as Zidisha.org, a purely peer-to-peer organization that does not work with partners, and UnitedProsperity.org which is based in India. CARE International has also launched its own internet-based service called lendwithcare.org.

- CSR and Corporate Waqf

Some MFIs in Indonesia are utilizing Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) funds from business organizations, usually state-owned enterprises and multinational corporations that have large funding pools for CSR activities. A similar approach has been used in Malaysia and Turkey where funds are disbursed for social development activities. Examples include Johor Corporation and Sabanci Foundation.

To complement funding through awqaf, Islamic micro-finance institutions can also create a financing model based on perpetual source of funds, which has been done by few IMFIs in Pakistan. The awqaf microfinance model is indeed a new frontier that should be further studied and in time extended to more countries.

- Zakat Funds

The first priority in using zakat funds is to eradicate poverty by assisting the poor and the needy. Zakat and waqf institutions certificates usually raise funds that can be used in providing microcredit. However, micrentrepreneurs may misuse the granted financing by using it for consumption rather than for project investment. Implementing an integrated Islamic microfinance model incorporating the two modes of financing (zakat and waqf) may resolve fund inadequacy problem of IMFIs (Hassan, 2010). Covering their basic needs of consumption by the utilization of zakat funds, micro-entrepreneurs will be incentivized to allocate all the remaining resources to succeed in their businesses. Additionally, they will benefit from lower refundable loans, as no return can be realized from zakat funds.

Regulatory and Supervisory Environment for the Microfinance Sector

In most developing countries prudential regulations of financial institutions focus mainly on capital requirements and supervisory control through onsite and off- site monitoring (Arun and Turner, 2002). But efficient monitoring of MFIs requires a developed institutional environment which is generally reflected in the form of efficient legislative and accounting systems. Meanwhile, the implementation of regulatory and supervisory reforms is costly, especially for small financial institutions like MFIs. However, the benefits of implementing best practices in terms of regulations and supervision might overcome the disadvantage of its higher costs (Theo- dore & Loubiere, 2002).

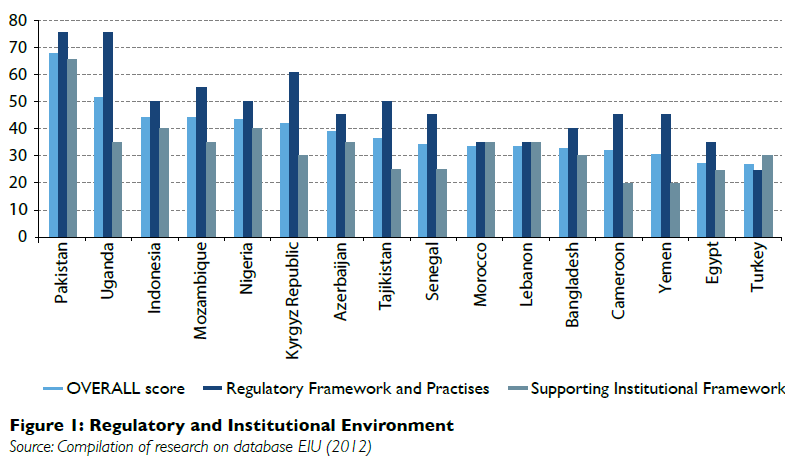

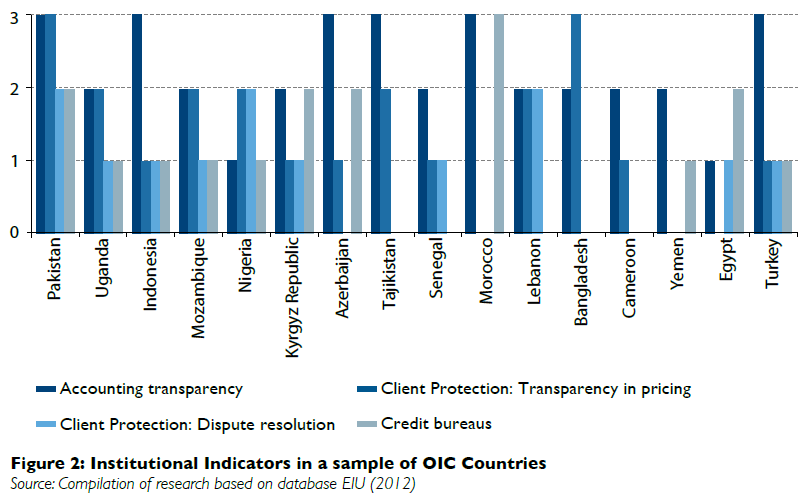

Most dimensions of the institutional environment are common to Islamic and conventional MFIs in OIC countries. Using the Global Microscope on the Microfinance Business Environment, 2012 database2 Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the development of the regulatory and institutional environment in some OIC countries.

Most MFIs in different OIC-countries are registered as cooperatives and non-governmental organizations. They do not operate under a dedicated financial legal status, but in the existing legislations which have been reframed to regulate microfinance institutions. Cross-country regulations vary according to the indicators. Pakistan is positioned first (Overall Score 67.4 out of 100), followed by Uganda (51.6) and Indonesia (44.3), while Turkey came at the last (Overall Score 26.6), right after Egypt (Overall Score 27.4) and Yemen (Overall Score 30.4).

Countries with developed microfinance industries, like Pakistan, Indonesia and Uganda, display strong regulatory and supervisory systems. Specialized governmental institutions (like central banks) appear to play a major role in pressurizing MFIs to perform better in terms of client protection, risk management and innovation. They help to develop the banking infrastructure, encourage the use of good practices, and provide regulatory and supervisory mechanisms to enable MFIs to develop viable business models. As these institutions are important means to put into effect regulatory and supervisory frameworks, there is a need for a supportive legislative framework to be set at one fell swoop. Reforms have to be implemented in OIC countries with the objective to improve the regulatory framework. Parallel reforms in legislative system would enforce the process. Besides, efficient business disputes resolution ensures MFIs’ credibility and enhance their reputation.

The accounting practices in Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Morocco, Pakistan, and Turkey show a relatively advanced level of transparency with a score of 3 out of

- Egypt and Nigeria are the worst performing in this dimension among the set of considered OIC countries with a score of 1 out of 4. In terms of transparency related to the pricing of the microfinance services, Bangladesh and Pakistan are again among the better-performing countries (score 3) ahead of Lebanon, Mozambique, Nigeria, Tajikistan, and Uganda (score 2). However, there is an evident lack of pricing transparency in Azerbaijan, Cameroun, Indonesia, Kyrgyz Republic, Senegal, and Turkey (score 1) and Egypt, Morocco and Yemen (score 0). Another important indicator of the institutional ecosystem of MFIs is the exiting of credit bureaus. In this regard, Morocco is the best performing (score 3) while Bangladesh, Cameroon, Lebanon and Senegal are the worst

performing (score 0). Microfinance activities, including credit, saving and insurance services are similar to banking activities from financial and institutional perspectives. It is recommended that the authorities set the regulation following a gradual approach based on public/private cooperation (Macchiavello, 2012). The role of private cooperation’s with international organizations, like inter-national microfinance networks, rating agencies, social investors and CGAP which release their own guidelines and standards serving as extra informal regulatory power, may contribute to fill regulatory gaps. By developing their own consumer protection codes and monitoring and enforcement mechanisms, these institutions show MFIs how to properly behave in order to raise funds.

Client Protection and transparency are fundamental for the development of IMFIs. Customers who trust the credibility of the IMFIs would voluntary save their money in that institution. There is also a greater probability of channeling zakat, waqf or tabaru’ funds to IMFIs. Low income customers often have lower education levels and have limited experience in formal financial services. They may use sophisticated Islamic microfinance products without fully understanding them if they trust the IMFI. In addition, transparent IMFIs are more likely to raise funds from commercial Islamic banks.

Challenges Facing the Development of Islamic Microfinance in OIC Countries

The development of the IMFIs requires the enhancing of the regulatory and institutional frameworks. Mohieldin et al. (2012) analyze the financial inclusion status of 37 OIC countries compared to other group of countries, namely OPEC and OECD. They point out that IMFIs are exposed to the absence of accounting standards, the lack of qualified working staff in Shari’a rules, the disconnection of principles of Islamic finance with real economy, and the limited efforts made to attract potential Islamic clients. We present in the following the actions that should be implemented in priority.

- Reinforcing the Regulatory and Supervisory Frameworks

The regulatory framework has the ultimate goal of protecting the entire financial system. It is set to license IM- FIs and to define the rules based on general standards to which the latter has to stick, like capital adequacy, minimum capital requirements, corporate government requirements, financial disclosers, loan loss provision and reserve requirements. It consists of prudential and non-prudential regulation. When a deposit-taking MFI turns out to be insolvent, it becomes difficult for it to repay its depositors especially when it is a small institution. In order to mitigate the inherent risks of systemic financial instability, the financial authority requires from the IMFIs to comply with prudential regulations to protect their financial soundness. The compliance with such regulations will also facilitate the access to commercial and non-commercial source of funds, improve the standards of control and reporting and thus achieve growth and outreach goals (Rhyne, 2002). However, prudential regulation is costly, officious and relatively difficult to be practiced by MFIs, contrary to non-prudential regulation which is much easier to apply as it focuses only on preserving the interests of customers and investors.

Regulation and supervision must be jointly set. Regulation without supervision and enforcement instruments is useless. Supervision is a public financial authority duty, typically based on the recommendations by the Basel Committee on Banking and Supervision which present the Basel Core Principles (known as Basel II) as the suitable framework for supervisors of deposit-taking MFIs. Supervision is occurs in two ways: on-site and off-site supervision. On-site supervision concentrates mainly on information systems of MFIs, their credit and governance systems, internal control within each institution and portfolios evaluations. Off-site supervision focuses on providing supportive data analysis for eventual on-site inspections.

- Implementing Client Protection Principles

The Smart Campaign is a global effort aiming at unifying microfinance leaders worldwide around a common goal which provides MFIs with the necessary tools and resources to protect clients. It has mobilized around 1000 retail stores and a number of networks and associations. The Smart Campaign’s client protection principles considers 7 principles (previously 6) including appropriate product design and delivery, prevention of over-indebtedness, transparency, responsible pricing, fair and respectful treatment of clients, privacy of client data, and effective mechanisms for complaint resolution. These principles are essential for the sustainability of any inclusive financial system. They should be implemented not only to protect already existing clients from eventual abuses or losses resulting from IMFIs’ failure or other reasons, but also to ensure the confidence of potential future clients. According to a study survey by MIX Market in 2011, consumer protection has been recognized as an important element for MFIs to practice good ethics and smart microfinance. However, only 15% of the representative MFIs implement all six Smart Campaign’s client protection principles, while 69% fully disclose prices, terms and conditions of their products to customers prior to sale. 44% indicated that the corporate culture and the human resource system of their institutions are being judged with high standards of ethical behaviour.

IMFIs that are committed to enhancing client benefits and to operating profitability are expected to put the principles of responsible finance into action by implementing client protection principles. In Pakistan, the Code of Conduct for Consumer Protection was set to overwhelm the mistrust of clients and to guarantee the credibility of the whole microfinance sector. By signing the code the MFIs agree to provide the terms and conditions of all their financial services to clients which must be written in an understandable language, which includes the effective service charges, the repayment schedule, principal and mark-up, and any affiliated products and extra fees that may be applied later.

- Implementing Appropriate Risk Management Practices

Risk management is an important factor for the sustainability of MFIs. Instruments of risk management and insurance in the IMFIs scarcely differ from the conventional MFIs’ practices as they are based on principles of mutual guarantee (kafalah) and collateral (daman). In case of group lending, mutual guarantees are used by almost all MFIs, both conventional and Islamic, while very few IMFIs, like the Indonesian BMTs and the Lebanon-based Hasan Fund, require physical assets as collateral.

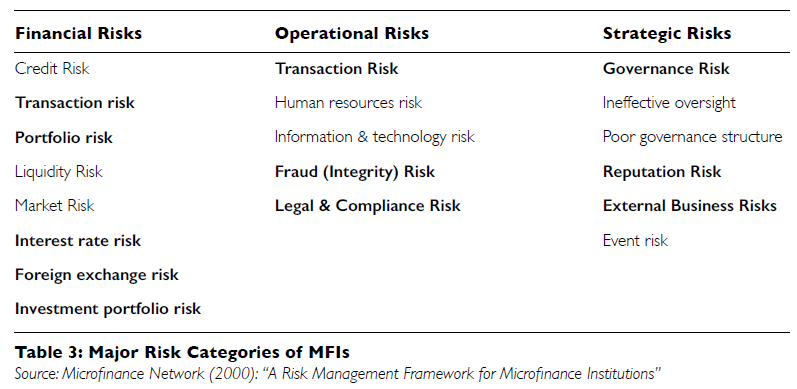

The sophistication of risk management systems varies with the size, the type and the complexity of the MFI.Table 2 lists different MFIs’ risks, which are categorized into three types: financial risks, operational risks and strategic risks. Financial risks are common in both MFIs and IMFIs. Nevertheless, IMFIs may face additional forms of credit risk resulting from the innate aspects of the Shari’a-based contracts. In Murabaha contracts, for instance, risks may occur from the non-delivery of the items from the supplier or failing to adhere to the repayments schedule, or even the refusal of the client to buy the merchandise that the IMFI has already purchased. In these cases, the IMFI can neither increase the amount of the mark-up, nor force the client to buy the item.

IMFIs have to assess and manage the various risks inherent to their activities. There is an increasing need to design risk management tools and approaches that meet with IMFIs clients’ specificities, lending methodologies and social and financial performance objectives. Micro takaful can serve as an efficient loan protection scheme when borrowers do not repay the loan. Social sanctions and religious ties can also prevent “committed” borrowers from misuse of their loans which may affect IMFIs’ portfolio quality.

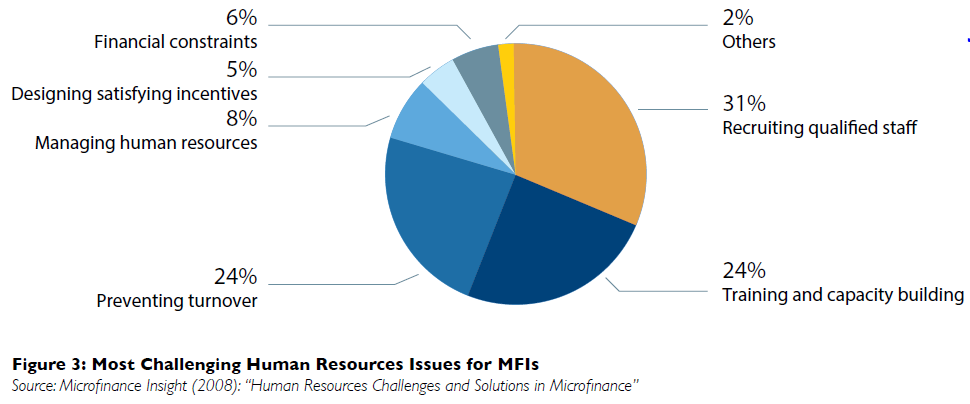

- Enhancing the management of human resources

In general, the clients of IMFIs lack education about Islamic financial principles and standards. Providing trained managers and staff for IMFIs would cast doubt on the adherence of these institutions to such rules and principles. The staff of IMFIs is required to have qualifications in both microfinance and Islamic finance. Ongoing training for staff workers can be an efficient way to improve their professional skills and keep them engaged in their work. According to the survey report by Microfinance Insight in 2008, 54% of sampled MFIs offer training programs one or two times a year, while 39% of them offer it more than 4 times a year. 16% of MFIs that offer trainings more than 4 times a year consider their environment as “very competitive”. Overall, the majority of sampled MFIs indicate that human capital is the most challenging issue among others like financial and technology issues. They explain that recruiting qualified, providing relevant training and capacity building and preventing turnover are their priorities as they are the most difficult to ensure. Training programs should be develop over time with modifications and changes that aim at improving IMFIs’ efficiency and performance (Khan, 2008). Developing human resource functions and market research also contributes in capacity building services for microfinance services providers whose main concern is to keep up with the fast changing financial inclusion landscape.

Ensuring consistent staff training, advisory services and skills building are essential in building capacity services able to cope with all aspects of the sector from the regulatory and supervisory entities through to information systems to public authority agents and funding providers.

- Adopting new distribution strategies

Similar to their conventional peers, IMFIs need marketing strategies to achieve financial stability, sustainable performance, enhance customer loyalty and, thus in-crease profitability (Churchill and Halpern, 2011).These strategies include corporate branding, target market identification, product delivery systems and customer services approaches. Among the marketing strategies that the IMFIs can adopt include advertising, sales promotion, public relations, face-to-face marketing, etc. However, given the lack of infrastructure in rural districts and the higher operational costs, IMFIs should use alternative ways to provide banking services to poor unbanked citizens. Developing branchless banking is an innovative distribution channel which should be considered. Branchless banking uses different technologies including internet, mobile phones, POS (Point Of Sale) and ATM (Automated Teller Machine) networks. The sustainable growth of telecommunications and retail industries in many devolving countries was at the origin of the development of this new banking system. Issuing electronic money (E-money or E-wallet) by non-bank companies offer the possibility to poor customers to store, pay and exchange money in their region with no need to recourse of commercial banks.

The development of branchless payment infrastructure by governments could be encouraged for their useful- ness to social programs targeting safety and inexpensive transfer of funds to the poor. Indeed, conditional cash transfer programs have gained immense interest by governments and international organizations. It has been adopted by over 60 middle-income developing countries where many of them have developed their own branching banking business models. However, limiting the programs on social payment will not lead to broader financial inclusion (Pickens, Porteous, and Rot-man, 2009). Offering savings accounts to beneficiaries of the programs, like in India, South Africa and Brazil may smoothen the progress.

Elephant in the Room: Impact on Poverty Alleviation

Among the 192 member countries of the United Nations, over 130 of them are classified as developing countries which are in general facing high unemployment and poverty rates. According to estimates by the World Bank, more than 1.6 billion people were classified as poor in 2009, with the majority living in rural areas. In 2011, 58.4% of the developing world’s total population was either poor or near poor while this rate reached 30.2% in the Middle East, 61.1% in North

Africa and 92% in South Asia. Poverty is related to the lack of employment opportunities mainly in developing countries due to demographic growth, skills mismatches, rigidity of the labor markets, and weakness of the private sector. The OIC member countries, with a population of 1.57 billion people, had an unemployment rate (9.4% in 2010)4 which exceeds the global rate (6% in 2011).

The role of conventional microfinance in poverty alleviation is well documented, particularly in context of rural development (Khandker, 2005), financial inclusion (Cull et al., 2013) and improvement in the income of poor household (Imai et al., 2010). Similarly, the contribution of the Islamic microfinance movement in reducing the incidence of poverty is conceptually significant and important. According to a CGAP study, there are more than 600 million of Muslims who live with less than US$2 a day, of whom nearly half would not accept financing support or loans from interest-based institutions (El-Zoghbi and Tarazi, 2013). This is certainly a significant incentive to create IMFIs

Although there are some studies that assigned the role of poverty alleviation to Islamic banks, such as an important report by Dhumale and Sapcanin (1999) in the MENA, the different needs of micro-entrepreneurs and the poor make it harder for Islamic banks to serve this segment. The creation of specialized IMFIs is seen as a necessity, and there is evidence that links these MFIs with poverty alleviation (Kaleem and Ahmed, 2010, Rahman, 2010).These studies again provide only conceptual and theoretical arguments for Islamic microfinance.

A more robust assessment on the impact of Islamic microfinance to poverty is urgently required. At the same time, the Islamic microfinance sector should be developed further to create any meaningful impact. Where IMFIs constitute only a fraction of the microfinance movement, any attribution to poverty reduction of a country or a community can still be debatable. What has been agreed by many observers is that IMFIs have the potential to contribute to poverty alleviation in many Muslim countries, since the scale of the Islamic finance sector will increase over time.

Conclusion

The research on microfinance has evolved through the decades, both conceptually and empirically. The growing body of knowledge in microfinance is also due to the rapid development of microfinance sector, indicated by the increasing number of microfinance institutions in the past three decades. While pioneers like Grameen Bank, BancoSol and Bank Rakyat Indonesia remain prominent players in their respective markets, the number of players competing in the microfinance markets has certainly increased significantly. This is evident from the cases studies highlighted in preceding sections, as well as the number of MFIs recorded in microfinance databases such as MIX Market.

The same can be said about Islamic microfinance. As indicated in the 2013 CGAP report cited earlier, Islamic microfinance is an important sector (or sub-sector) in the global microfinance movement. A significant number of Muslims live in poverty and so there is certainly growth potential for IMFIs in these countries. 40 % of Muslims worldwide surveyed by CGAP in 2008 and 2009 have a preference for Islamic modes of financing. However, in most of these countries, Islamic microfinance institutions (IMFIs) are not operating under a dedicated financial regulation framework. Consequently, they are facing similar difficulties and impediments than their conventional peers. Understanding the regulatory and institutional environment is primordial for enhancing the Islamic microfinance.

Another problem is that there is a shortage of studies in the literature that examine the feasibility and reliability of Islamic microfinance schemes. The existing literature on the subject is largely conceptual and normative, which provides little information on the current status of IMFIs, and much less evidence on the performance of these institutions. This gap provides an exciting opportunity for many researchers to examine more closely the important and highly debated aspects of Islamic MFIs, such as mission drift issues, trade-off between financial performance and social impact or profit vs. outreach, impact of rising competition from commercial banks, commercialization or even impact assessment.