Introduction

Discussing taxation can be a turgid affair given the difference in regime policy. But as the global Islamic finance industry grows, there is a need to look into best practices particularly for emerging domestic Islamic financial sectors to emulate or consider. Perhaps the best example is Malaysia, a jurisdiction which has created a regulatory infrastructure that accommodates both conventional and Islamic finance. A dual financial sector presents an interesting balancing act as legacy tax obligations, specific for conventional products, can be triggered, which may unduly increase the costs of Islamic financial products. Thus this chapter explores the way Malaysia has tackled Islamic financial products in relation to tax policy. We then move from the domestic to the international. This chapter will look at some of the tax policy challenges facing OECD governments in the context of international business. It then considers how these can impact upon the taxation of international Islamic finance transactions and makes some recommendations regarding the way forward.

Part 1: General Taxation of Islamic Products in Malaysia

The supportive tax treatment of Islamic finance adopted in Malaysia has very much helped to shape and spur growth in the local, and indeed the global, Islamic financial scene as a whole. Malaysia as a jurisdiction, which bases its taxation on a territorial basis, assesses income accruing in or derived from Malaysia or received in Malaysia from outside Malaysia. The corporate income tax rate for corporations is currently levied at 25%, but following the recent Budget 2014 announcement, the tax rate is set to be reduced to 24% from year of assessment (“YA”) 2016.

Although Malaysia does not have a capital gains tax regime for which gains on disposal of properties or as- sets which typically underlie Islamic securities are taxed on, there is real property gains tax (RPGT). A variation of capital gains tax, RPGT is chiefly imposed on gains arising from the disposal of real property and shares in real property companies (i.e. companies which own a significant amount of land and/or buildings). Other taxes in Malaysia which are relevant to the Islamic financial sector are transactional taxes such as stamp duty and service tax. The recently introduced goods and services tax (GST) of 6% which is set to come into effect on 1 April 2015 would also be an important element to consider for the Islamic financing sector moving forward.

Normally, several transfers of underlying assets would need to legally (at least on paper) take place before- hand, or joint profit arrangements entered into between two or more parties before financing transactions can qualify as being Shari‘a compliant. The legal documentations would vary depending on the Islamic principle adopted in respect of the security or financing scheme. Examples of Islamic principles commonly used in Shari’a-compliant securities are:

- Murabaha i.e. the sale of goods at cost plus an agreed profit mark-up;

- Musharaka i.e. a partnership financing agreement be- tween two parties or more to engage in a specific business activity;

- Ijara e. a lease agreement; and

- Mudaraba i.e. an agreement between a capital provider and entrepreneur to enable the entrepreneur to carry out business Profits will be shared

at a pre-determined ratio and losses will be borne by the capital provider.

dents as well. In short, all tax rules relating to interest will equally apply to Islamically generated profit.

It should be noted that often, more than one Islamic principle can and is used to structure a single Islamic security. One would appreciate that under ordinary circumstances, and given the wide range of Islamic principles available, the tax treatment of Islamic financing structures would need to be analyzed accordingly on a transaction by transaction basis, and determined using general tax principles. This may, and frequently does, lead to complex and prohibitively expensive (direct and indirect) tax implications which do not reflect the true nature and substance of the financing transaction.

Bearing this in mind, Malaysia does not actually have specific tax legislations which govern Islamic financial transactions. The way Malaysia manages to facilitate Islamic transactions within the existing conventional legal and regulatory frameworks is by including several amendments to prevailing legislations which effectively give Islamic transactions a “neutral” or equal footing to that of conventional financing transactions. More specifically, new sections and definitions were inserted to the major governing tax acts: Income Tax Act 1967, Real Property Gains Tax Act 1976, and the Stamp Act 1949. For example, the simple, yet profound answer with regards to the “age-old” question on how financiers are meant to profit from Shari ‘compliant securities since riba is prohibited from being charged (which has been the conventional means for banks) is by simply treating profit payments which form part of Islamic financing arrangements comparable to interest payments under conventional financing.

This is provided for under Section 7 of the Income Tax Act 1967:

“Any reference in this Act to interest shall apply, mutatis mutandis, to gains or profits received and expenses incurred, in lieu of interest, in transactions conducted in accordance with the principles of Shari’a”; and

Section 1(5) of Schedule 2 of the Real Property Gains Tax Act 1967:

“Any reference in this Schedule to interest shall apply, mutatis mutandis, to expenses incurred in lieu of interest, in transactions conducted in accordance with the Shari’a.”

Since profits are equivalent to interest for tax purposes, the taxability and deductibility of profit payments are similar to the treatment of interest in a conventional sense. A practical example of this would translate to profits received by Islamic banks – Islamic financing provided to customers would be treated just like interest income would to a conventional bank, and correspondingly tax deductible to the customer if funding has been used for business purposes or for the purchasing of assets to generate income. Also, profits received by customers from Islamic banks will be treated as having received interest for tax purposes, and will be taxed or exempted accordingly. This includes payment of with- holding taxes on interest out of Malaysia to non-resident.

As mentioned above, the intricate mechanics of Islamic financing arrangements which typically involves the movement of assets or properties between borrower and lender also present challenges from a tax perspective. The second “neutrality” provision under the Income Tax Act 1967, Section 2(8), provides:

“(8) Subject to subsection (7), any reference in this Act to the disposal of an asset or a lease shall exclude any disposal of an asset or lease by or to a person pursuant to a scheme of financing approved by the Central Bank, the Securities Commission, the Labuan Financial Services Authority or the Malaysia Co-operative Societies Commission as a scheme which is in accordance with the principles of Shari ‘where such disposal is strictly required for the purpose of complying with those principles but which will not be required in any other schemes of financing” .

What the above Section means is that the underlying exchange (sale and purchase) of asset or lease which are integral parts of Islamic financing transactions will be ignored for income tax purposes. As such, gains arising (if any) from the unique disposition of Islamic financing transactions would not be taxable, thus catering for the many different Shari’a principles available for use. This not only eliminates tax uncertainty for all relevant parties from originators to investors and borrowers alike, but also promotes a conducive environment for players to pursue and explore innovative Islamic business activities and products in Malaysia. It is however, important to note that in order to avail the favorable tax treatment under Section 2(8), the proposed Islamic financing scheme has to be approved either by the aforementioned regulatory bodies. Where the Islamic product or facility does not receive approval by any of these regulatory authorities, the tax neutrality provision under Section 2(8) would not apply, and the transaction would need to be analyzed separately, and taxed in accordance with general tax provisions.

Aside from treating profit as interest, and disregarding underlying movements of assets or properties for Shari ‘purposes, Section 60(I) of the Income Tax Act 1967 also provides:

“(1) For the purpose of this Act, where a company establishes a special purpose vehicle solely for the issuance of Islamic securities, any source of the special purpose vehicle1 and any income from that source shall be treated as a source and income of that company and such company shall have the right to receive and utilize any proceeds derived from the issuance of such Islamic securities.

(2) The special purpose vehicle is exempt from the responsibility of doing all acts and things required to be done under this Act…”

This section facilitates certain types of Islamic transactions and products such as sukuk, making them more efficient and lowers the cost of financing. Hence, where a special purpose vehicle is established solely for the purposes of Shari ‘compliance to channel funds, the special purpose vehicle issuing the sukuk shall be exempted from income tax. Similar to Section 2(8) of the Income Tax Act 1967 however, Section 60(I) would only be available if prior regulatory approval is obtained.

The next key tax implication relevant to Islamic financing transactions is stamp duty. In Malaysia, stamp duty is chargeable on instruments and not on transactions. If a transaction can be effected without creating an instrument of transfer, no duty is payable. Stamp duty rates which vary from as low as MYR10 (approximately GBP2.00) to 3% ad valorem of the transaction value may apply depending on the agreements entered into. Typically, Islamic transactions have several agreements to reflect the underlying (re)sale or lease of asset/property, and again, without tax neutrality, stamp duty costs can run high. Under Paragraph, General Exemptions in the First Schedule, Stamp Act 1949, the neutrality provision states:

“An instrument executed pursuant to a scheme of financing approved by the Central Bank, the Labuan Financial Services Authority, the Malaysia Co-operative Societies Commission or the Securities Commission as a scheme which is in accordance with the principles of Shari’a, where such instrument is an additional instrument strictly required for the purpose of compliance with those principles but which will not be required for any other schemes of financing.”

From the above, it is clear that taxation functions as the underlying and common driving force of the Islamic financial sector in Malaysia, indirectly encouraging compliance through taxation. Regulatory bodies such as the Securities Commission, the Labuan Financial Services Authority, and the Malaysian Central Bank approve and oversee all Islamic financial transactions, in addition to issuing guidelines, policies, and frameworks to suit and promote the overall Islamic financial system.

Tax Treatment of Islamic Products and Transactions

Today, the Malaysian market offers a variety of Islamic financial products, thanks to one of the pioneering initiatives which catapulted the growth of Islamic finance in Malaysia: the introduction of the Skim Perbankan Tanpa Faedah (SPTF) or Interest-Free Banking Scheme (IFBS) in March 1993 by the Malaysian Central Bank. The IFBS basically served as an open invitation for conventional banks in Malaysia at the time to venture into the Islamic financial market. This resulted in a flurry of excitement with banks seizing on the opportunity of first mover ad- vantage in this niche market segment. Islamic insurance or Takaful and Islamic fund management also grew and flourished alongside the Malaysian Islamic banking sector.

Common examples of financial products issued in Malaysia include sukuk, ijara arrangements, Islamic facilities, Takaful products, and Islamic Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs). A simplistic and brief discussion on these products and their taxation are as follows:

- Sukuk– Sukuk Musharaka and Ijara Arrangements

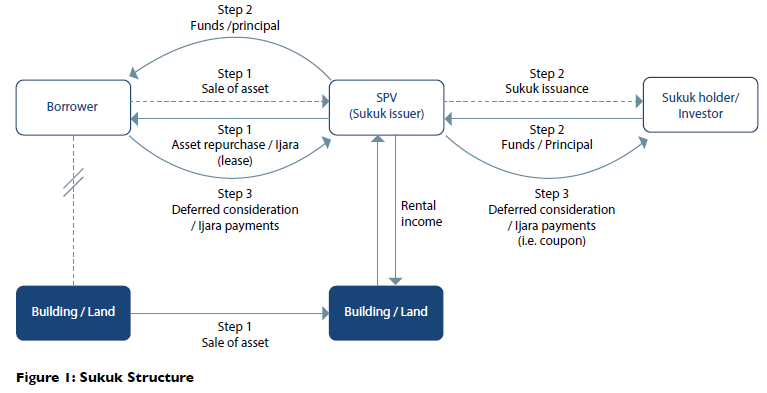

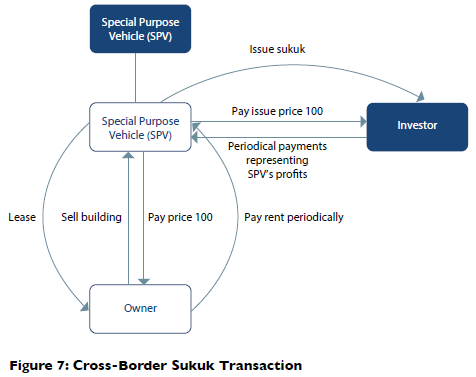

Sukuk issuances based on the musharaka principle involve business partnership arrangements from which investors would be paid a profit out of their investment over a period of time. sukuk musharaka structures involve income generating assets such as buildings or land from which lease or ijara income generated serves as the business income for the partnership. In order for there to be a partnership arrangement between a bond issuer and bondholders, a special purpose vehicle (SPV) is formed to issue bonds to investors based on an expected return of the asset i.e. the coupon rate (which the borrower would have had first injected the asset into the partnership SPV). This is similar to an asset-backed vanilla structure, illustrated in Figure 1.

By applying the neutrality provisions, the sale and lease-back (including the resale of asset at maturity) of building or land will be ignored for purposes of taxation i.e. it is assumed that no movement of asset has occurred. And where the structure has been approved, the SPV shall be disregarded for Malaysian tax purposes such that all income and expenses of the SPV will be treated as be- longing to the Borrower. So in essence, the lease payments for the use of asset will be seen as simple coupon payments to sukuk holders.

- Islamic Facilities – Commodity Murabaha Facility

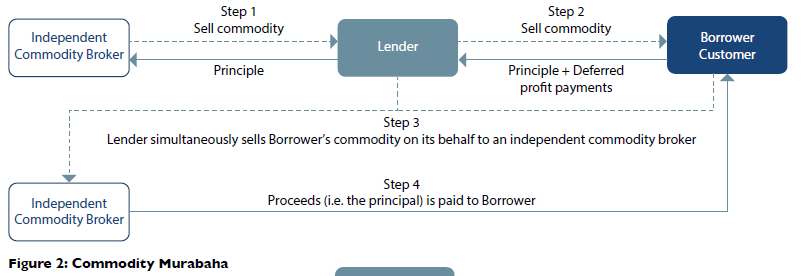

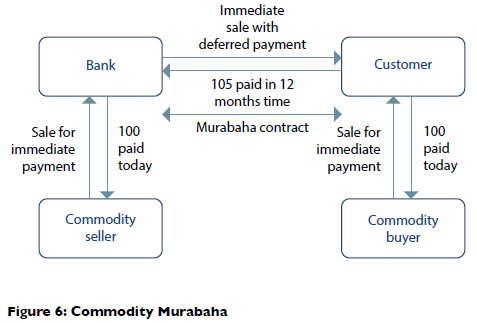

A common structure used in Malaysia especially where there is no ready asset on which the provision of Islamic financing is typically based on, is the issuing of commodity murabaha facilities. Under this structure, commodities such as gold, crude oil, tea, coffee beans etc. which are tangible in nature are used as underlying assets to fulfil Shari’a requirements. Under the murabaha concept, Lenders sell commodities to Borrowers at an agreed mark-up. How the Borrower Customer repays the Lender will be on a deferred basis, hence mimicking a principal and interest arrangement similar to that of a conventional loan. A diagrammatic representation can be seen in Figure 2.

From a Malaysian tax perspective, the Lender would be seen as providing a loan to the Borrower. Profit income will be treated as taxable interest income, and from the Borrower’s perspective, profit payments are treated as tax-deductible interest expense. Such a “look through” tax treatment would need prior approval from relevant regulatory authorities as highlighted above.

- Takaful

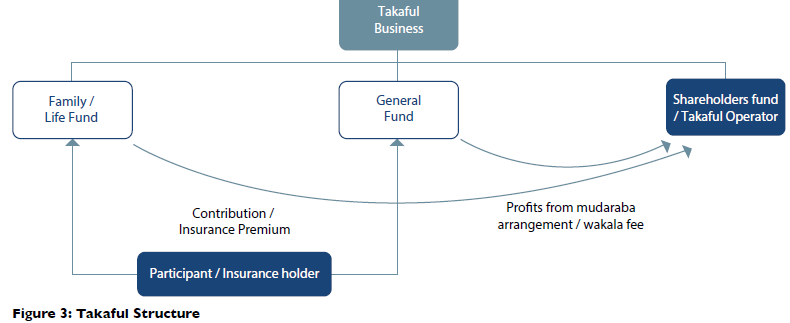

Takaful operators segregate contributions received into tabarru (donation) and investment funds. The tabarru fund is created for the purposes of meeting policyholders’ desire to protect each other from defined risks and mishaps.

The two concepts adopted in Malaysia are the mudaraba and wakala models. Under the mudaraba model, a partnership is formed between a capital provider i.e. rabb-ul-mal, and another which contributes effort, managerial and/or entrepreneurial skills (mudarib). Profit from the outcome of the venture is shared between the capital provider and manager/ entrepreneur according to a mutually agreed profit-sharing ratio, while losses are generally borne solely by the capital provider. The wakala or agency model involves the manager/entrepreneur charging a wakala fee for managing participants’ takaful fund instead. Liabilities for losses would be borne by participants. The structure of takaful operators can be seen in Figure 3.

Usually, takaful operators have three funds: Life (Family), General, and Shareholders’ funds. The prescribed tax treatment of each type of fund is complex, different, and varies in accordance with the Income Tax Act 1967. Similar to conventional Life insurance, Family funds are taxed at 8%, while General and Shareholders’ funds are subject to tax at the prevailing 25% income tax rate.

- Islamic REITs

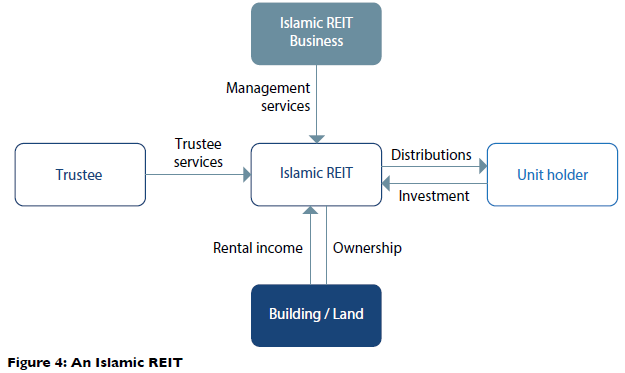

A REIT or a “property trust fund” is a unit trust scheme that invests or proposes to invest primarily in income-generating real estate. REITs in Malaysia are principally governed by the Securities Commission of Malaysia (SC), and are managed by management companies approved by the SC. Trustees are appointed to hold the properties of the trust. Islamic REITs operate in a similar fashion and are bound by other additional Shari’a requirements. An illustration of the mechanisms can be seen in Figure 4.

In essence, REITs are trusts, and trusts in Malaysia are taxed like any ordinary company. Although most investment income earned by REITs is generally not subject to corporate income tax, the taxation of a REIT currently depends on the amount of income that is distributed to unit holders. If a REIT distributes 90% of its taxable income, tax transparency rules will apply, and the REIT would not be subject to corporate income tax. How- ever, if this 90% condition is not met, the REIT would be subject to tax at the prevailing corporate income tax rate of 25%, with general deductibility rules applying to the REIT. The taxation of unit holders on the other hand depends on their individual tax profiles. As a general rule, if the REIT has been subjected to tax, there would not be any further tax on unit holders. If however the REIT is not taxed, unit holders would be taxed accordingly on receipt, or withheld at source through a with- holding tax mechanism.

Tax Incentives for the Islamic Financing Sector

In addition to laying in place the necessary Islamic financial infrastructure which ensures Islamic products are treated the same as conventional products, Malaysia also provides tax incentives on corporate income tax, stamp duty, and other miscellaneous tax deductions.

Among them are:

- Income tax exemption for Islamic banks, International Currency Business Unit (ICBU), Takaful companies and units, on income derived from businesses conducted in international currencies including transactions with Malaysian residents up to YA2016;

- Tax exemption for 5 consecutive years given to Islamic banks from payment of income tax in relation to sources of income derived from its overseas branch or investee company. Application for the approval of the branch or investee company to carry out banking business must be received by Bank Negara Malaysia between 24 October 2009 until 31 December 2015 and approval for tax exemption shall be made by the company to the The branch or investee company shall commence Islamic banking business within two years from the date of approval issued by Bank Negara Malaysia;

- Income tax exemption for approved fund management companies managing foreign and local investors’ funds established under Shari’a principles up to YA2016;

- Tax exemption to an individual, unit trust or listed closed-end fund from the payment of income tax in respect of any gains or profits received from the investment in Islamic securities, other than convertible loan stock, which are issued in accordance with the principles of mudaraba, musharaka, ijara, istisna or any other principle approved by the Shari’a Advisory Council established by the Securities Commission un- der the Capital Markets and Services Act 2007;

- 10 year stamp duty exemption on instruments executed pertaining to Islamic banking activities in foreign currencies undertaken by International Islamic Banks and ICBU from YA2007 until YA2016;

- All stamp duty costs relating to the issuance of any sukuk pursuant to any Shari’a concept or principle as described in the Securities Commission (Prescription of Islamic securities) Order 2004 is exempted pro- vided it has been approved by the Securities Commission;

- 20% stamp duty remission on Islamic finance instruments as approved by Bank Negara Malaysia or Securities Commission from 2 Sept 2006 until 31 December 2015;

- Tax exemption on any profits paid out by Islamic banks to non-resident companies/institutions for deposits placed at the banks;

- Income tax deduction on expenses incurred prior to commencement of an Islamic stock broking business for companies which commence their businesses within 2 years from the approval date by the Securities Commission for applications received up to 31 December 2015; and

- Income tax deduction on expenses incurred on issuance of approved Islamic securities up to YA2015 for securities based on several principles such as Mudaraba, musharaka, ijara, and

Analysis and the Way Forward

It goes without saying that financial systems change constantly and indeed need to evolve to meet global and domestic market conditions and demands. There is no one single perfect system to adopt, but instead one to aim for which is simple, flexible, stable, and progressive. Malaysia has invested heavily in trying to realize this goal, and today after over 30 years of Islamic financing in Malaysia, it is one of the world’s leader and pioneers in Islamic finance. Having said that, however, there are still several areas of improvement which would help pave the way for further international growth of Islamic finance.

From an overall regulatory perspective, there is some-times a misalignment of objectives between the various government bodies which oversee and manage the Malaysian financial system. Although this sometimes occurs between regulatory authorities, interactions and relationships between regulatory authorities and the tax authorities are usually tested ever so slightly more. Inevitably, different policies and views occasionally flow through the system and create inefficiencies. An example in which there appears to be little joint effort be- tween government authorities as far as Islamic finance is concerned is having various tax incentives and treatments which do not include the same Shari’a principles or all have the same approving regulatory authorities. This indirectly restricts innovation, confining it to certain tax driven conditions, and sometimes resulting in industry players having to obtain an additional regulatory approval to enjoy equal or preferential Islamic tax treatment as others who received approval from a different regulatory authority. At times, the way the Malesion tax authorities interpret and administer certain tax treatments may not necessarily be aligned with the original intention and spirit of Islamic tax incentives. Fortunately, such cases are rare and often involve complex Islamic structures, which take time to resolve. To be fair however, instances such as these are not uncommon in the conventional setting and happen the world over; Malaysia is no stranger especially so amidst an uncertain and fragile global economy. Nevertheless, it can be safely said that concerted efforts on all fronts do and regularly point in the same direction, comfortably facilitating a healthy environment for Islamic finance in Malaysia.

From the above, we have seen that there are many positive attributes of the Malaysian approach to Islamic financing – although the domestic legislation in Malaysia promotes Islamic financing transactions, it does not however specifically accord or entice foreign players with the same treatment available to domestic players. To a certain extent, the historical development of Malaysia’s neutral and tax incentive-based model was primarily created to cultivate domestic growth at a time where there was no or little coordinated activity in Islamic finance globally. With increasing interest and a growing number of Islamic financial institutions exploring business opportunities outside their own jurisdictions and potentially looking to enter the Malaysian market, the existing Malaysian legislation and incentives should evolve in tandem with this economic shift.

In a globalized environment, as more cross-border transactions are entered into, there is a need for other governments to consider tax neutrality provisions to ensure that Islamic financial products are not worse off compared to conventional products. Until there is harmonization in the tax treatment of Islamic finance products in countries around the world, Islamic finance may not be able to grow as fast as one would hope on an international scale.

Much has been achieved over the years in developing Malaysia as an international Islamic financial centre. The integrated approach to regulation and supervision of Islamic finance which caters to the distinctive characteristics of Islamic financing operations has worked in Malaysia’s favour, and now exists neatly alongside the conventional system. Taxation, which drove and continues to drive market behaviour in Malaysia, has no doubt played an instrumental role in the domestic Islamic financial sector. Matters unresolved have avenues from which they can been ironed out, and with a financial system well equipped with a Shari’a Advisory Council comprising prominent scholars, jurists, and market practitioners advising regulators on matters relating to Islamic financial markets, products, services, transactions and activities, Malaysia is in a good position to continue reinventing and innovating the Islamic financial industry in 2014 and beyond.

Part 2: Tax Policy Changes Facing OECD Governments

The fundamental concepts that apply to the taxation of international business were developed during the latter part of the 19th century and the first years of the 20th century. The business environment was very different at that time.

Communications were very slow. Although a small amount of communication could take place at high speed using telegraph cables, there was very limited bandwidth to use modern vocabulary. Accordingly it was only practical to use telegraph for short high importance communications. Travel between distant locations on land relied upon railways with journey times measured in days or weeks while long-distance sea travel was slower still.

Despite the slowness of the communications and travel, international trade and international business did exist and grew steadily. There were two basic trading models.

- Exporting to Foreign Customers

Consider a UK manufacturer who has found a customer in Malaysia.3 The customer relationship may have been established by the UK manufacturer sending a salesman to Malaysia or by the Malaysian enterprise sending someone to the UK to find appropriate suppliers.

The UK manufacturer having agreed a quantity and price with the Malaysian customer will ship the goods to Malaysia. The manufacturer may require payment up-front, or may require the Malaysian customer to secure payment (for example by a letter of credit accepted by a UK bank) or may be willing to accept taking on the Malaysian customer’s credit risk. Questions regarding payment arrangements are not considered further in this chapter and have no impact upon the tax treatment. Quite often the goods will be shipped by using a third-party carrier; ownership in the goods may pass when the UK firm delivers them to the shipping agent or may remain with the UK firm until the shipping agent delivers the goods in Malaysia.

The UK government will clearly wish to tax the UK manufacturer on any profits made as the manufacturer is resident in the UK and carrying out manufacturing there.

Salesman negotiates and agrees the contract. In some cases this may be made clear by domestic law but in most cases one relies upon double taxation treaties agreed between the countries. Under such a treaty the norm would be that the UK manufacturer would not be taxable in Malaysia unless the manufacturer had a “permanent establishment” there as discussed below.

- Setting up a Foreign Branch

As an alternative, and particularly if the Malaysian market is likely to be important on a continuing basis, the UK manufacturer may set up a branch in Malaysia. This would likely involve owning or renting premises where a stock of goods would be maintained. The UK manufacturer would probably send some UK employees to be based in Malaysia at the premises, as well as recruiting some local Malaysian staff. The Malaysian branch would be expected to find customers, make sale contracts and provide after-sales service.

The goods would continue to be manufactured in the UK but the manufacturer would ship appropriate quantities to the Malaysian branch where they would be stored until the Malaysian branch found customers and made sales.

In these circumstances the UK manufacturer clearly has a substantial and continuing connection with Malaysia through its branch. In international tax language, such a branch is referred to as a “permanent establishment.” It is an accepted norm of international taxation that the country where the branch is located, here Malaysia, can tax the profits made by the branch. The branch can prepare accounts reporting its sales, deducting its local costs and deducting something for the cost of the goods that the branch obtains from its “head office” which is the UK manufacturer. The norm for tax purposes is to treat the branch as acquiring the goods at the same price that would be paid by a third party purchaser in the same circumstances, irrespective of how the manufacturer and the branch actually account for the transfer of the goods from the UK to Malaysia.

There are two alternative ways for the home country, here the UK, to take account of the Malaysian tax being paid by the UK manufacturer’s branch in Malaysia.

- The home country may exclude the profits of the Malaysian branch from home country taxation. This approach has long been adopted by countries such as France and

The question is whether Malaysia can tax the UK manufacturer on the profits made from selling the goods to the Malaysian customer. Some countries may wish to tax this profit, particularly if the contract for the sale of the goods is negotiated and made within Malaysia by the UK firm’s salesman who has travelled there to negotiate the sale.

Over time the international convention has developed that a country in the Malaysian circumstance described above does not seek to tax the UK manufacturer on the grounds that the UK manufacturer does not have a sufficient connection with Malaysia, even if a travelling

- The home country may tax the profits of the Malaysian branch since the branch is an integral part of the manufacturer, but then allow the manufacturer to deduct the Malaysian tax paid when paying its home country tax, assuming that the Malaysian tax does not exceed the home country tax on the branch profits. (If it does, the excess may either be ignored completely for tax purposes or the manufacturer may be allowed to carry it forward for possible credit in the future period if the home country tax on the branch profits exceeds the Malaysian tax in that future) The USA and the UK have historically taken this approach of taxing the foreign branch with a credit for the foreign tax paid.

- International Investment

As well as trade in goods, the latter part of the 19th century also saw a growing level of international investment in real estate, shares and loans. Such activities also give rise to international tax questions:

- A UK bank makes a loan to a Malaysian customer who pays interest to the UK bank. Can Malaysia tax the UK bank on this interest income? At what rate?

- A UK investor purchases a building in Malaysia and rents it to a Malaysian The same questions arise with regard to the rent paid to the UK investor.

- If the UK investor later sells the Malaysian building and makes a gain, can Malaysia tax the gain?

Again, it has become the norm for countries to address such questions when negotiating double taxation treaties. The UK/Malaysia treaty will specify whether Malaysia can tax the items mentioned above; if Malaysia can tax, the treaty may specify the maximum rate of tax that can apply. Such tax is often referred to as withholding tax since typically the country from which the payment is made will require the payer to deduct the tax when making the payment and remit that tax to the tax authorities; this avoids the need for the tax authorities to require the foreign recipient to file a tax return, particularly since there are limited enforcement mechanisms available where the recipient is overseas.

Current Difficulties with the Previous International Tax System

Unlike the late 19th century, international communications are now very cheap and essentially instantaneous with no meaningful limits on bandwidth. Travel between far distant countries is rapid and relatively cheap using jet aeroplanes.

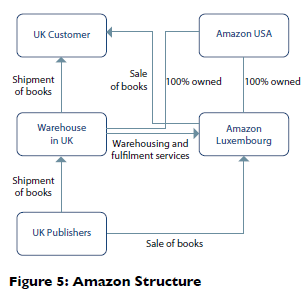

This is leading to the above categorization system breaking down. Consider how Amazon.com sells books in the UK as illustrated in Figure 5.

In this simplified illustration, the parent company Amazon USA has two subsidiaries, one in the UK that owns and operates a warehouse and one in Luxembourg that carries on a business of selling books. Amazon Luxembourg purchases books in bulk from UK publishers. The publishers are instructed to ship the books to the UK warehouse where they are stored. However the owner-ship risk in the books rests with Amazon Luxembourg which will suffer the loss if the books cannot be sold at appropriate prices.

When a UK customer uses the website www.Amazon.co.uk to purchase a book, the contract is actually made with Amazon Luxembourg which receives payment from the UK customer via his credit or debit card. Amazon Luxembourg will instruct the UK warehouse to ship the book to the UK customer.

The UK warehouse never owns any books and takes no business risk in respect of the books. All it does is to charge Amazon Luxembourg for warehousing and fulfilment services, making a relatively small profit which is taxable in the UK. Amazon Luxembourg makes profits from the sale of books, assuming that they can be sold for more than cost. That profit is made in Luxembourg where Amazon Luxembourg is based and not in the UK as Amazon Luxembourg does not have any place of business in the UK. The Luxembourg tax on the book-selling profits is much lower than would be the tax paid if the business were carried on in the UK.

For simplicity the US tax treatment of the foreign subsidiaries is ignored. However there are various complex mechanisms which ensure that the USA does not tax either Amazon Luxembourg or the UK warehousing company.

Somewhat similarly, Google has a significant workforce in the UK whose responsibility is to help UK advertisers make the best decisions regarding the kind of advertising services they wish to purchase from Google. However all of Google’s advertising services in the UK are sold and delivered electronically from Google Ireland so the advertising services are taxable in Ireland and not in the UK.

The Policy Response

Issues such as those described above are causing OECD countries to reconsider how international business should be taxed. On 19 July 2013 the OECD published its “Action Plan on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting” which discusses in more detail the kind of issues out- lined above and proposes how tax authorities might

International Islamic Finance Transactions

Islamic finance is the provision of finance within the rules of Shari’a as specified by the Islamic finance scholars who advise the Islamic financial institutions (IFI) and other Muslim counterparties involved. Typically Islamic finance involves carrying out transactions in real assets to achieve the same economic consequences that would be achieved in conventional finance by making interest-bearing loans.

Two specific examples are considered below.

- A Cross-Border Commodity Murabaha

Transaction

In this example (See Figure 6 for diagrammatic representation,) a foreign bank enters into a commodity murabaha transaction to provide short-term finance to a customer within the country under consideration. Here the foreign bank purchases a commodity such as refined copper from a commodity broker located within the country and sells the commodity to a customer located within the country. It is quite likely that the bank may have some agents located within the country that organize and facilitate these transactions rather than carrying them out entirely remotely. The customer is then responsible for selling the commodity to obtain cash. In practice the bank may help to facilitate that by introducing the commodity buyer to the customer and may even act as the customer’s agent in carrying out that sale. The precise details of how much the bank can assist the customer in selling the commodity will depend upon the advice of the Shari’a scholars.

When persons based in a country regularly carry out purchase and sale transactions on behalf of a foreigner (the bank) they may cause the foreign bank to have a permanent establishment within the country. This is a complex area of tax law but the risk of a permanent establishment is a very real one. The consequence would be that the bank’s profit from the purchase and resale transaction would be subject to tax within the country at the full rates of tax applicable to business profits.

In comparison, the international norm is that interest paid by a person such as the customer to a foreign bank would either not be taxable at all by the country where the customer is located or would be subject only to withholding tax at a rate significantly lower than the full rate of tax applied to business profits.

- A Cross-Border Sukuk Transaction

As this transaction is relatively complex, it is worthwhile describing the precise steps involved (See Figure 7).

- Owner is a company located in the

- At commencement, (“today”) Charity which is located overseas and is not connected with Owner creates a company called Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) which is also located

- Owner owns a building which it purchased many years ago for US$20 Today, after SPV has been formed, Owner sells that building to SPV for a price of US$100 million payable in 30 days’ time.

Today Owner gives SPV a purchase undertaking by promising that if in five years’ time SPV offers to sell the building to Owner for a price of US$110 million, Owner will buy.

- Today SPV gives Owner a sale undertaking by promising that if in five years’ time Owner offers to buy the building from SPV for a price of US$110 million, SPV will sell.

- Today SPV rents the building to Owner with a lease which is five years The rent is US$5 million per year, payable once a year with the first payment in 12 months’ time.

- SPV creates sukuk certificates under which it declares that it holds the building, the lease and the benefit of the Owner’s purchase undertaking as trustee for whoever is the owner of the sukuk certificates.

- Between today and day 30 the sukuk certificates are sold to investors for a total price of US$100 million. All of the investors are located

- On day 30, SPV pays the US$100 million to Owner which is owed for the purchase of the building.

- In 12 months’ time, Owner pays rent of US$5 million to SPV immediately passes that rent on to the investors in proportion to their ownership of the sukuk certificates. The same happens at the end of years 2, 3, 4 and 5.

- Also at the end of year 5, Owner offers to buy the building from SPV for a price of US$110 SPV agrees to sell, as it has promised to do under the terms of its sale undertaking. Owner pays US$110 million to SPV and SPV transfers ownership of the building to Owner.

- SPV passes the US$110 million sale price of the building on to the investors in proportion to their ownership of the sukuk certificates.

- The sukuk certificates are cancelled as they have no further value as SPV has no remaining

- After completion of the above transactions, as SPV should have no assets and no liabilities, SPV.

The steps involved in creating, operating and unwinding this structure give rise to a number of tax questions. These include the following:

- Does the sale of the building by Owner to SPV trigger a charge to tax on the US$80 million (selling price US$ 100 million less original cost US$20 million) capital gain on the building?

- Although the SPV is overseas, the building is located in the same country as Owner. Does that country seek to tax the US$10 million gain when SPV sells the building back to Owner at the end of year five?

- Is there withholding tax on the rent which Owner pays to SPV?

- SPV has declared that it owns the building in trust for the investors. Accordingly when one investor sells a sukuk certificate to someone else, legally he is selling a fractional interest in the building. Does the country in which the building is located seek to tax any gain which the investor makes on that sale?

- Many countries charge tax on the transfer of real estate. Is real estate transfer tax chargeable on the sale of the building from Owner to SPV or the sale back from SPV to Owner?

- Is real estate transfer tax chargeable on the sale of sukuk certificates, since they represent an ownership interest in the building?

If these tax costs do arise, they are likely to make the sukuk transaction prohibitively expensive and unworkable. As a comparison, no such taxes would be expected to arise if Owner had issued a conventional bond to the investors, with the possible exception of withholding tax on interest paid to the investors. However even in the case of withholding tax, it is sometimes the case that rental income suffers a higher rate of withholding tax than interest income. The opposite rarely occurs.

The Tax Policy Risks and a Proposed Way Forward

OECD governments are under great fiscal pressure as a result of the aftermath of the global financial crisis. This has been aggravated by the scope for internationally mobile businesses to fragment their activities between countries to reduce their taxes payable, taking advantage of the ease of modern communications and travel.

Governments are likely to respond to the challenges discussed above by increasing the number of circumstances in which a foreign person having some kind of activity within the jurisdiction is treated as having a tax-able presence. This would mean modifying the existing definitions of “a permanent establishment” within international tax treaties so that more kind of activity would constitute a permanent establishment. There may also be an increased desire to charge withholding taxes on payments being made to foreign persons.

Such measures if enacted are likely to cause collateral damage to the Islamic finance industry by increasing the likelihood of taxation on Islamic finance transactions, where such taxation would not arise on a conventional finance transaction. For example, in the case of the commodity murabaha transaction mentioned above, any moves to tighten the definition of a permanent establishment are likely to increase the risk that the foreign bank is found to have a permanent establishment in the country where the murabaha transactions are taking place. This would cause the foreign bank to suffer tax in that country whereas the making of a conventional loan may well be exempted from tax. Similarly, the transactions involved in the sukuk arrangements are likely to face higher taxation than the issue of a conventional bond.