Introduction

Wealth management is complex topic that entwines many different considerations of an individual. Primarily, the individual has to be conscious about the way his or her income can be used to generate positive returns to ensure security and comfort. Takaful and pension plans are, outwardly, two different models purposed for two different objectives: insurance against adverse circumstances and money for old age, respectively. Yet, they both share the fundamental principle of compassion at the time when one is in need.

This chapter explores both takaful and pension plans. The first section looks at the former and focuses on improving governance of takaful institutions, and explores how the governance of takaful institutions is important in enabling growth. The second section focuses on pension plans and particularly the need for pension plans for expatriates in the MENA region. This is a growing group and as they settle in their respective countries, the need for pension plans tailored for them in retirement is imperative.

Part 1: Global Takaful Governance is being Put to the Test

It is frequently said, and widely considered by industry practitioners, that takaful is a subsector of Islamic banking and finance (IBF). Others may disagree, and believe that takaful has emerged as a separate and independent industry discipline in the Shari’a-compliant world of service and products offerings. Perhaps what is more agreeable among industry stakeholders is that takaful is a less developed segment of the wider industry and faces a number of challenges to reach mass markets level. Yet, what is intriguing is that the sustainable growth of IBF in general will stimulate additional growth in the takaful sector as finance and insurance services are intertwined.

Nevertheless, takaful is now being put to test with more compelling regulatory and practice challenges that will impact its growth markets and sustainability. These emerging challenges have been addressed by Deloitte’s IFKC research, completed in the summer of 2013. The three-level approach to the industry research created a knowledge-sharing dialogue between policymakers, practitioners and academics. It is also worth noting that the debate with prominent industry leaders included participants from key markets in South East Asia, the Middle East and Europe and has produced an interesting culture of knowledge-sharing among industry thought leaders.

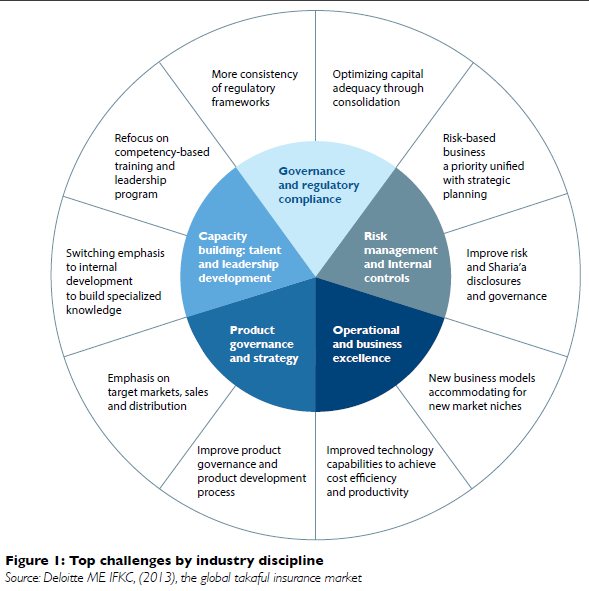

The industry challenges and capabilities required were grouped in ten challenges in five industry disciplines as shown in Figure 1. Key takeaways can be summarized in the three prime areas of concerns to the industry executives, namely: regulation, practice and business support.

The Regulatory Level: Strengthening the Regulatory Capacity

In the face of some macroeconomic challenges, strengthening the regulatory frameworks of takaful requires focused effort and the support of all industry stakeholders. National regulators as well as industry standard-setting bodies (SSBs) need to work together to take bold actions and initiatives to improve takaful and policy-making processes.

Evidently, there is a need for more consistent regulatory frameworks amongst key markets and regulators. Optimizing capital adequacy through consolidation will achieve growth and sound corporate structures. Takaful operators are being challenged by greater transparency and oversight from different regulatory and self-regulatory organizations, which require increased reporting and self-disclosure exercises that will necessitate greater investment in technology and information management.

Further complications exist because of the inconsistent takaful regulations around the world. Takaful operators are often faced with the burden of tailoring their product features, distribution approach, statutory reporting and disclosures, employment regulations, and in some parts of the world such as the GCC, hiring, to take into account the particular national regulatory requirements of markets in which they wish to operate. This is likely to persist for some time unless drastic regulatory harmonization is achieved. Moreover, market conduct regulation around the world is becoming increasingly intrusive and judgment-based, with regulators demonstrating readiness to intervene at all stages of the business cycle. This seems less of a regulatory concern in the takaful industry, and operators are left without adequate scrutiny in product governance and offerings. This is particularly true in the case of complex investment-linked products.

The Practice Level: Risk Management & Internal Controls

With a confluence of regulatory changes likely to impact the international expansion of takaful, executive management and boards are advised to strategize risk management functions and governance. Shari’a compliance risk should be embedded in all phases of operations and management. This effectively means that takaful companies will be better equipped for a business cycle that develops new, innovative products and services, penetrates new markets, competes with conventional counterparts, and be better prepared for adverse market turbulence and shocks. In essence and more practically, making risk-based business a priority unified with takaful operators’ strategic planning. In addition, improved risk and Shari’a disclosures and governance is pivotal for good practice and better performance.

However, on the operational front, takaful operators should embrace technology in all operational, sales and marketing strategies. Operators could achieve cost efficiency and improve productivity through the building of technology capabilities to tap into new markets and increase revenue. This could be supported with new business models to accommodate for wider niche.

A key requirement for practice development will probably rely on the importance of developing a robust product governance system to ensure that policyholders and customers are treated honestly, fairly and professionally.

The bottom line is that takaful operators should continue to explore new niche markets and develop specialty products and tap into mass markets in Indonesia, Egypt, Turkey and KSA. Meanwhile, takaful providers are required to invest in educating consumers about their product offerings.

The Support Level: Capacity-building initiatives

The role of leadership and talent development in takaful has become increasingly important in recent years and takaful operators are poised to seek sourcing quality human development solutions and advisory. Industry executives need to switch emphasis on internal development to build the specialized knowledge and skills required and refocus on competency-based training and leadership programs.

Evant today, describes pension plans in the GCC as “extraordinarily generous to those they cover.” As a result of the attractive incentives offered by these schemes, roughly nine out of 10 male workers in the GCC retire by the age of 60, according to the Booz report, compared with one in 10 in the OECD.

The drawback, however, is that these generous pension schemes do not extend to expatriate workers. As the Booz report puts it, “perhaps most damaging of all to the GCC’s future economic development has been the GCC’s policy of excluding productive non-national labor from its pension programs.” This, says Booz, might be less of an issue in a region that did not pin so much of its economic fortunes on foreign-born workers. But three-quarters of GCC-based employees are expatriates, while in the UAE and Kuwait the proportion is 83% and 82% respectively.

Pension Systems in the GCC Compared with Asia

The human capital and talent challenge in the takaful industry is exacerbated by the shortage of skilled and qualified personnel, and the subsequent high turnover rate this causes. This has created a pressing need for specialized skills in areas of underwriting, risk management, and product development.

Takaful operators should strategize talent development and knowledge base in Islamic finance and takaful, and explore personal, technical and professional attributes deeply.

Three key influences that should be addressed to build an effective competency-based training strategy:

- Skill assessment and gap

- Knowledge and skills

- Development of a professional education encompassing three capabilities described above.

Part 2 : Pension Plans for Expatriates in the Middle East and North Africa: Sharing the Burden

Globally, there has been a discernible shift in recent years towards risk-sharing between the public and private sectors in the provision of pension cover, with defined benefit (DB) schemes increasingly being complemented or replaced by defined contribution (DC) programmes. This process is being driven by a mix of demographic and financial trends, with life expectancy levels rising dramatically at a time when governments worldwide are coming under increasingly pronounced fiscal pressures.

Although these pressures may appear to be less immediate in some parts of the MENA region than in the EU or Japan, even in the wealthiest economies of the Arab world, governments are increasingly recognizing the need to address the issue of their pension time-bombs.

A Booz & Co analysis1, published in 2009 but still rel Pension systems in the GCC differ markedly with those in key Asian financial centers, such as Singapore and Malaysia, which offer government-sponsored provident funds to all local employees. By contrast, in the UAE1, for example, the current practice is for companies to provide expatriate employees with an end-of-service (ES) lump sum based on the number of years of service. This system, which has been enshrined in UAE labor laws for a number of years, is increasingly regarded as inefficient for the government as well as for employees. Given that the majority of expatriate workers in the UAE are estimated to send up to half their salaries home, this system is unsatisfactory from the government’s perspective because it drains much-needed resources away from the domestic economy.

According to the Booz analysis, if the GCC expanded pension coverage to non-nationals, the contribution fund would in some cases grow three-fold, reflecting the number of additional contributors. This would help to add considerable depth to local financial markets.

Expatriate workers’ dependence on employers’ end-of-service benefit (EoSB) payments, meanwhile, leaves them vulnerable in the event of the bankruptcy of their employers, especially given that in the majority of cases end of service liabilities are either underfunded or un-funded. This vulnerability became all too apparent in the economic downturn of 2009 and 2010. According to SEI2, “across the region, corporate cash flows were tight and, in some cases, non-existent, resulting in corporate restructurings and bankruptcies. This left many employees as creditors to the firm or, put simply, receiving none of their EoSB.”

Grasping the Nettle of Unfunded EoSB

Research published by Towers Watson suggests that a rising number of companies in the Middle East are addressing the issue of unfunded EoSB. The number of companies indicating that they are now funding their EoSB, at least in part, rose from just eight in Towers Watson’s 2009-2010 survey3 to 24 in 2010-2011, a growth of 200%. “This is a significant increase in one year and falls into line with Towers Watson’s view, particularly given the projected sharp rise in ESB liabilities over the next 10 years or so that companies should be looking to fund benefits (at least in part) as far as possible, ”Towers Watson notes. “Such funding, preferably under an external trust, may help to achieve greater security for the employees’ ESBs.”

At a broader level, the public and private sectors in a number of leading MENA economies are exploring new solutions for ensuring that adequate retirement cover is offered to all local employees. In the UAE, for example, Dubai’s Department of Economic Development has been in discussion with the World Bank on the introduction of a mandatory pension system for employees not covered by the present scheme.

Government-backed pension initiatives are likely to be especially beneficial for small and medium-sized enterprises that are the backbone of the economy in the UAE. SMEs will continue to spearhead economic dynamism and diversification in the UAE, according to SEI’s most recent survey, in which 80% of respondents indicated that they expect their headcount to grow in the next three years. About 34% of this increase is expected to come from smaller companies with fewer than 200 employees, while 37% will be generated by medium-sizes operators with a headcount of between 200 and 999.

In the meantime, the private sector has been looking at initiatives that would provide added pension security for expatriate workers. For example, in February 2013 the NBAD Trust Co, a wholly-owned subsidiary of the National Bank of Abu Dhabi (NBAD) announced the launch of its Today Wealth Builder, specifically designed for companies employing expatriates. As the local press explained at the time of the launch, this is essentially a “packaged corporate structure underpinned by a range of investment fund options that employees can choose based on their risk appetite. ”These schemes are individually tailored, with regular payments made either solely by the company or by both the employer and employee.

Efficient Pension Provision:

A Competitive Edge

Employers contributing schemes of this kind are not motivated purely by altruism. In an environment in which the region’s financial centers, in particular, are competing intensely to attract top-quality staff, the provision of generous and secure retirement programmes is increasingly being identified as giving employers a competitive edge. As NBAD Trust Services has said, “by offering employees a cost-effective and professionally managed savings solution, employers will be able to demonstrate that they have the long-term interests of their staff in mind. This will have a powerful and positive impact on their ability to recruit and retain high-quality employees.”

Competition for talent is likely to intensify rather than ease over the foreseeable future. According to SEI’s latest report, a recent survey by Robert Half, the 2013 UAE Salary Guide Report, indicates that 85% of executives are concerned about losing their top performers over the next year. The result, says SEI, is that “human resources departments are under pressure to consider retention strategies and rewards for employees that link compensation to length of service.”

The Importance of Health Insurance

If the provision of more efficient pension schemes are increasingly regarded as a competitive advantage for employers, so too is the offer of group medical coverage, which is now seen by most companies as a prerequisite for attracting and retaining talent. The most recent Mercer Benefit Survey for Expatriates and Internationally Mobile Employees found that 98% of companies now provide medical benefits coverage to their globally mobile employees, up from 57% in 2005.

Governments in the GCC are progressively introducing mandatory health cover systems. For example, the Advisory Council of Qatar enacted its new health insurance law in June 2013, requiring mandatory coverage for all Qatari nationals and visitors. According to Towers Watson, the Qatar government picks up some 73% of the country’s annual expenditure on health care of almost US$2.8bn. “The requirement for additional contributions to the mandatory health care system will help to reduce this expenditure and shift the burden more toward employers, ”Tower Watson advises.

In Dubai, meanwhile, according to new regulations recently rolled out by the Dubai Health Authority (DHA), companies employing 1000 or more employees are required to provide medical cover to all their staff by October 2014. Those with between 100 and 999 employees have until July 2015 to comply, and by June 2016 even those with fewer than 100 will need to have followed suit.

Responding to Demographic and Fiscal Pressures

A number of MENA countries have other powerful incentives for overhauling their pension systems. According to a report published in 2012 by the Kuwait-based Markaz,10 the generous welfare system in the GCC is exasperated by the Elderly Support Ratio, which calculates the degree to which the youth population is able to support the aging and retiring. By global standards, this ratio is currently high in the GCC. But as Markaz warns, “a stark reversal is expected in just 40 years, when this ratio is expected to drop to the low single digits across the GCC. This essentially means that by 2050, Kuwait, for example, will have just three working-age persons supporting one senior citizen; this will constitute a major strain on resources for the country.”

Demographic trends across the broader Arab world are, however, even more unnerving, and point to the need for an urgent rethink of pension policies in scores of Muslim-majority countries. “The projection for an ageing population in the Arab world is alarming,” notes a recent report published by Milliman. “Its tsunami effect will be catastrophic because family or tribal support is disappearing. We are also moving towards a financial economy rather than a real economy, which means we are becoming more dependent on financial instruments for our survival. According to the UN’s recommendations, funded pension plans can be a panacea for this problem.”

The Turkish Blueprint

A striking example of a MENA economy which will face growing demographic and fiscal pressures is Turkey, which is developing what may be a blueprint for private pension systems across the MENA region. According to UN projections, the share of the Turkish population aged below 24 will fall from 50.4% in 2000 to 35.7% in 2030. Among major economies in the Muslim world, only Egypt (where the share is forecast to plunge from 55.7% to 28.1% in the same period) is undergoing a more rapid ageing process.

Turkey’s unfavourable demographic dynamic, combined with a low savings rate aggravating the perennial problem of the country’s current account deficit, has been an important driver of legislative change designed to promote the growth of private pensions. Under the revised pension law, which came into force at the start of 2013, the government contributes an amount equal to 25% of the sum paid by individuals into private pension schemes. At the same time, a range of tax incentives have also been introduced aimed at boosting domestic savings.

With a private pension fund to GDP ratio of just 2%, according to PriceWaterhouseCoopers12, the long-term growth potential for the industry is self-evident. Already the passage of the new law has led some private pension companies to double their target for the industry’s assets in 2023 from TRY143 billion (US$67 billion) to TRY300 billion (US$138 billion), compared with TRY19 billion (less than US$10bn) in 2012. Aside from increasing the savings rate and helping to reduce Turkey’s current account deficit, this will underpin the expansion of the country’s insurance and asset management industries, supporting the growth of Istanbul as a financial center.

The Potential of Shari’a-Compliant Pensions

Dovetailing with MENA governments’ commitment to promoting more sustainable pension systems in recent years has been the increased depth, sophistication and adaptability of the region’s financial systems. More particularly, the recent expansion of the Islamic financial services industry worldwide has underpinned robust growth in the takaful sector.

The investment policies and annuity principles of the conventional pension system mean that these schemes are unacceptable with devout Muslims, given the payment of riba twinned with the element of gharar arising from the unpredictability of life expectancy and therefore of annuity payment streams. There is, however, a growing recognition that the takaful industry is well-positioned to provide Shari’a-compliant solutions to those eager to reconcile their religious beliefs with the need to cater for a comfortable retirement.

One product that is being explored as a means of avoiding all these elements is the Islamic equivalent of government longevity bonds, known as longevity sukuk, which pay declining coupons each year after a given age (typically 75) rather than any principal. According to Milliman, “the underlying spirit of takaful fits squarely in the government longevity sukuk concept through the mechanism of wa’ad (promise or undertaking).”

Products such as these will provide an important building block for Shari’a-compliant pension programmes. As Linklaters observes in a recent update on Islamic annuities, “the costs associated with increasing lifespans across the world are well known. The nascent Islamic pensions industry will only develop if Shari’a-compliant means of dealing with longevity risk are developed.”

Conclusion

Leading takaful operators realize that despite regulatory reforms and the importance of good practice in governance, takaful is highly dependent on subject matter expertise and professionals with Shari’a acumen who are able to lead innovations and change in the practice. The heightened focus on governance, fiduciary responsibility, risk management and accountability are direct consequences of the global financial crisis and will likely present the sector with challenging practices and regulatory issues during the next five years. Such changes are not easy to contemplate or implement, but the longer strategic governance capabilities building is delayed, the more difficult it might be to streamline takaful solutions and increase penetration to mass markets. For now, senior executives of takaful insurance should at least begin assessing how the challenges might affect their ability to generate growth, profitability and expansion of the industry. Each of the issues discussed pose a threat as well as a potential opportunity for growth.

With regards to pension schemes, Shari’a-compliant products will form a small but growing component of the market for defined contribution schemes. More generally, it is clear that the long-term prospects for conventional as well as Islamic pension providers are bright, and that opportunities will continue to be underpinned by growing demographic and fiscal pressures through-out the MENA universe. In the GCC, meanwhile, expansion of opportunities for private pension funds will also support the growth of the asset management and life insurance industries. This will, in turn, make a key contribution to the expansion and diversification of the financial services industry in regional centers such as Dubai.