Introduction

There is always something incomprehensible about structured products to investors, and none more evident than with securitization, generally viewed by investors in the Middle East as a complicated investment. On the face of it there is some truth in this perceived complication based on the number of parties involved in the transaction (including various third-party service providers), an array of historical data to assess, collateralization to be factored in and enforceability issues to be squared off, not to mention in some instances rating agency requirements to be catered for.

Securitization is a relatively untapped market in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), with comparatively fewer transactions than in other parts of the world. However, various indicators anticipate the future growth of securitization transactions from the GCC.

Securitization provides a possible solution for many institutions, both financial and corporate, as an alternative source of long-term funding at relatively lower rates, and as a tool for balance sheet management. From residential mortgages, to auto loans to consumer finance, the classes of assets are diversified and as the GCC expands and develops with infrastructure spending in the GCC “estimated at a total US$2 trillion over the next 20 years”1, coupled with the number of corporate financings obtained on short term facilities that are coming up for maturity, securitization provides a viable alternative source of funding.

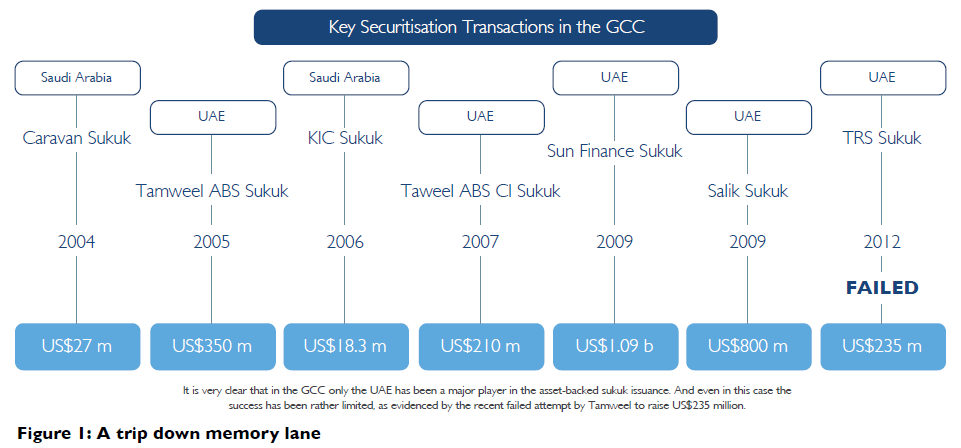

A Trip Down Memory Lane – Key Securitization Transactions in The GCC

Prior to the global financial crisis, securitization was in its infancy where there were few securitization transactions coming to market with issuers frequently having to push the boundaries of structured products in their respective jurisdictions. Saudi Arabia was at the forefront of that market. The first Islamic securitization transaction was launched in March 2004 for the amount of SAR 102 million (US$27 million) involving a Saudi Arabian special purpose company acquiring a pool of vehicles and underlying vehicle lease agreements from HANCO Rent A Car via an offshore SPV, registered in Jersey (CARAVAN I Limited). In turn, the SPV issued Shari’a compliant ijara investment sukuk securitizing the Saudi-Arabian car fleet inventory over a three-year term with the proceeds of synthetic risk transfer through a dual SPV structure.

In 2006, Kingdom Instalment Company (KIC) issued Shari’a-compliant asset-backed securities. It was the first residential real estate-backed securitization in Saudi Arabia. The issuance was for the amount of US$18.3 million and was backed by US$23.5 million pool of receivables. The certificates were over-collateralized by 28%, included a Shari’a-compliant guarantee by the International Finance Corporation (part of the World Bank Group) of 10% of the outstanding principal balance of the sukuk and an additional first-loss guarantee from a real estate development company Dar Al- Arkan, in an amount equal to 10% of the original face amount outstanding of the sukuk.

The UAE became the second key player in the GCC when in May 2005 the Emirates National Securitization Corporation issued a US$350 million rated securitization of domestic mortgages originated by Tamweel PJSC (Tamweel) in Shari’a compliant manner. Then in 2007, Tamweel, through Tamweel Residential ABS CI(1) Ltd, is- sued US$210 million for asset-backed certificates, the first true sale securitization in both the UAE and the GCC region as a whole.

Sun Finance Limited, a Jersey SPV, issued Dh4.016 billion (US$ 1.09 billion) of sukuk certificates. The sukuk al-mudaraba al-muqayyada certificates were backed by scheduled instalment payments owed by sub-developers arising from the sale of plots of land on the Shams and Saraya developments in Dubai (the originator was Sorouh Real Estate PJSC). Sun Finance was the first sukuk to feature subordination, being structured into a senior A class and two further subordinate B and C classes. The transaction was over-collateralized, included an enforcement reserve fund, a liquidity reserve fund and an infrastructure reserve fund. The infrastructure reserve fund was pre-funded to the amount of Dh1.735 billion at closing to ensure the structure’s bankruptcy-remoteness by provisioning for all remaining infrastructure costs payable to contractors, project managers and supervising consultants, with an additional contingency on top. In addition, in 2009, there was the US$800 million securitization by the Dubai Department of Finance of receipts from the Salik road toll receivables. The transaction was recently restructured due to the high cost of funding originally agreed to between parties.

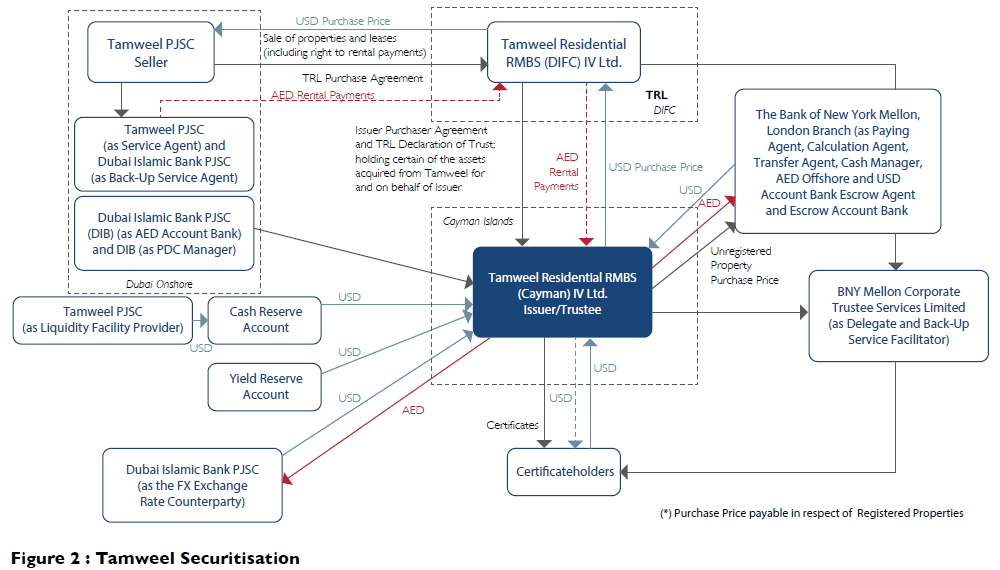

The most recent major transaction in the GCC was in 2012, when Tamweel attempted to issue US$235 million Shari’a-compliant residential mortgaged-backed securitization; however the transaction did not pro- ceed to completion after a number international road- shows. The transaction involved Tamweel Residential RMBS (DIFC) IV Ltd. (a DIFC incorporated special purpose company) (TRL) purchasing properties and related leases and rights from Tamweel PJSC. In turn, TRL entered into a purchase agreement with Tamweel Residential RMBS (Cayman) IV Ltd. (acting as Trustee and Issuer) whereby it would sell the properties and assign its rights to certain assets and rights acquired by it under the TRL Purchase Agreement to the Issuer (the Issuer Assets).TRL would act as title agent for and on behalf of the Issuer in respect of the Issuer Assets with legal title to the properties remaining in the name of TRL (as title agent for and on behalf the Issuer). Pursuant to the Declaration of Trust, TRL will declare a trust in favor of the Issuer over the legal ownership title to the properties. Pursuant to the Issuer Declaration of Trust and the conditions of the certificates, the certificates will confer on the Certificate holders the pro rata ownership rights to the Trust Assets and the right to receive payments arising from the Trust Assets. See Figure 2 for further details.

Except for Tamweel’s attempted issuance in 2012, we have seen no real Islamic securitization since 2009. In order to ascertain the lack of issuances, it may be helpful to analyze this from the perspective of Tamweel’s 2012 transaction. Tamweel’s certificates due 2046 would have been callable in July 2017 where the transaction would have been backed by properties and receivables related to the properties located in the Emirate of Dubai. As these were Shari’a-compliant mortgages based on ijara structures, the initial sale was based on a two-tier approach: [a] the sale and transfer of the properties and

[b] the assignment of the receivables from the underlying ijara and other agreements. The transaction was a true sale of assets and assignment, with various enhancements and protections for investors. Moody’s had provisionally assigned the floating rate certificates Aa3, six notches higher than Tamweel’s standalone credit rating of Baa3. Moody’s also commented that they believed that the true sale structure was a “robust” structure that warranted the credit rating assigned. Despite this, the feedback from some investors who were unsure was that the structure was too complicated for internal credit teams who were not well versed with structured products of this nature, particularly to review and decide within a short time period whilst the order books remained open. Another factor was that credit teams were not sure of the credit treatment in that they could not look through a Tamweel credit risk, yet ironically, the structure was prepared with a view to provide asset risk and not corporate risk.

Whilst we await the next possible attempt for a securitization from the GCC market – there are a couple in the making – it will be interesting to see how investor perceptions are addressed.

Legal and Operational Hurdles

Ensuring various elements of a securitization are enforceable under the laws of each jurisdiction in which the underlying assets are based is difficult. Add an extra layer of the rating agency and Shari’a requirements and the task seems destined for added complications. That being said, in the GCC the Tamweel 2012 transaction successfully showcased how Islamic principles and laws of the land can work simultaneously to achieve a desired outcome and provide rating agencies with the enforceability opinions required for a high rating. Set out below are some of the issues that needed to be resolved which are issues that may be factors hindering securitization.

Assignments

In the Tamweel 2012 transaction, there was an assignment of the leases and ancillary assets derived from the pool of assets sold. This provided the purchaser the right to the receivables from these contracts. In the GCC, the most common form of such a transfer is an assignment of receivables which allows for the transfer of all rights, title, interests, benefit and entitlement from the seller to the purchaser. For legal perfection of any such assignment and for such assignment to be enforceable in the UAE, actual possession and control of the asset is a prerequisite. Therefore, in the first instance there was a contractual assignment by the seller of all rights, title, interests and benefits in the contracts to the purchaser pertaining to all the properties sold. In order to give effect to such an assignment, the obligor must serve a notice of assignment to the counterparty notifying of such assignment to the purchaser and request the counterparty to acknowledge the receipt of notice to the purchaser. Whilst these formalities of notice and acknowledgment of notice is key to enforceability of such an assignment, it is an administrative burden for the obligor to write to potentially thousands of customers and seek their acknowledgment -putting aside the customer relations management point. The solution essentially lies in the underlying agreement in respect of the receivables. If the receivables contract is silent on the fact that the obligor benefits and receivables may be sold subject in a securitization or similar transaction then it would be necessary to follow the formality requirement for a valid and enforceable assignment. On the other hand in circumstances where the underlying contract expressly provides for assignment, then consent from the obligors will not be required as this pre-approval will be deemed to be acknowledgment. Therefore, it may be prudent for potential obligors to think long term and provide for such pre-approval in their standard form contracts with their customers.

Separately but related, once the assignment is effective, there also needs to be an operational certainty that these receivables will in fact be due and payable to the purchaser. The rating agencies also focus on this as a key point. Currently, most loans in the UAE are repaid by submitting a number of post-dated cheques to cover the instalment payments due, normally at least 24 months’ worth of instalments (if the tenor of the loan is longer than 24 months). In the Tamweel 2012 transaction, following the sale of receivables, these post-dated cheques had to be endorsed to the purchaser and delivered to the post-dated cheque manager who would submit these cheques for payment on their respective due dates for and on behalf of the purchaser of the receivables. This process of endorsing post-dated cheques can be extremely cumbersome and time-consuming, but in the absence of a more harmonized direct debit system of repayments of such loans, the endorsement of post-dated cheques was and will be the only viable alternative. Once the direct debit system is widely utilized in the UAE, the reliance on post-dated cheques may be overcome with a simpler system, similar to those used in the West. This will in turn simplify the process of mitigating operational risk in transferring the repayments to the purchaser

Security and Floating Charges

Pledges over accounts under Saudi and UAE law are enforceable only when the subject of the pledge is fixed. If money is being credited and debited to an account, the pledge becomes ineffective and re-pledging is required. This re-pledging is cumbersome and onerous and would require that the borrower re-pledges the security each time. Based on the foregoing, to better protect investors, accounts are often established in offshore jurisdictions such as England (in the name of the issuer) where the concept of floating charge is well-developed and tested. In the case of Tamweel, a frequent cash sweep mechanism was built in to ensure amounts received in the UAE where swept to the offshore account over which a valid and enforceable floating charge was taken.

Recently, in Saudi Arabia, a number of pieces of legislation have been put in place, creating an expanded regime for the registration of security interests for secured lenders. The new registration and filing systems are untested and not fully established as yet but should become important over time. The Saudi Commercial Pledge Law (Royal Decree No. M/75 dated 21/11/1424H (corresponding to 13 Jan 2004)) deals with taking security over moveable assets. An amendment to the Implementing Regulations of the Saudi Commercial Pledge Law (Ministerial Resolution No. 6320 dated 18/6/1425H (corresponding to 5 August 2004)) as amended by Ministerial Resolution No. 267/8/1/1812 dated 19/2/1431H (corresponding to 3 February 2010)) created the legal framework for a Unified Centre for Lien Registration (the Unified Centre). According to these amendments, the debtor and the creditor must register the security in the Unified Centre.

Securitisation Law

There is no law specifically dealing with securitization of receivables in the UAE (as with most GCC countries). The exception to this is Saudi Arabia which on 13/08/1433H (corresponding to 2 July 2012) enacted the real estate mortgage law. The real estate mortgage law comprises of a package of five separate laws, collectively referred to as the Real Estate and Financing Laws:

- The Real Estate Registered Mortgage Regulations No. 49, dated 13/08/1433H (the Mortgage Law).

- The Financing Lease Regulations 48, dated 13/08/1433H (the Finance Lease Law).

- The Law on Supervision of Finance Companies 51, dated 13/08/1433H (the Finance Companies Law).

- The Real Estate Finance Regulations No. 50, dated 13/08/1433H (the Real Estate Finance Law).

- The Execution Regulations 53, dated 13/08/1433H (the Execution Law).

The laws do not deal only with real estate mortgages but also cover other types of financing arrangements and assets including movable assets and intellectual property. The laws appear to be providing the legal infrastructure for potential growth for secured and/or structured financing industry however the laws specifically mention that foreign ownership restrictions apply and that securitization will be undertaken in accordance with the Capital Market Authority (CMA) regulations (see discussion in below regarding foreign ownership restrictions).

The Real Estate Finance Law provides real estate finance companies with the ability to refinance through

(i) another real estate financing company or (ii) the issuance of securities (including, but not limited to, securitizations) in accordance with the Capital Market Law. This is indeed a positive step in that the law is not only dealing with the primary market but also with the secondary market, which could develop into a very large and lucrative industry within Saudi Arabia.

Under the Finance Companies Law, any entity which is involved in the purchase, ownership or collection of receivables in Saudi Arabia with a view to securitization must be licensed to do so by the CMA. The entity will also be regulated in its activities by the CMA. If the purchaser does business with or via other sellers in Saudi Arabia rather than directly purchasing, owning and collecting the receivables, then these sellers must be appropriately licensed and authorized by the CMA to participate in such activities.

There are currently very limited codified regulations in the GCC governing secured transactions or mortgages, pledges and assignments, and the ability to create a legal, valid, binding and enforceable security interest is limited.

Taxation and Fees Issues with Securitisation

Tax or duties payable in respect of a sale or transfer of assets is always a concern when structuring transactions. Generally in the GCC, tax structuring for a securitization is not as critical as other elements (however we note the possibility of countries imposing tax on various elements of a transaction which are always factored in structures). In Saudi Arabia however, payments by a company or individual from a source in Saudi Arabia to a non-resident of Saudi Arabia (such as an offshore SPV) are subject to withholding tax of between 5 % and 20 % depending on the nature of the business.

The withholding tax does not apply to payments made on contracts for goods, but does apply to payments made for services, and at the rate of 5 % on interest payments under loan agreements. Accordingly, as was the case in the Sun Finance transaction, a dual SPV structure was required to mitigate taxation costs. There is hope that the Finance Companies Law, which addresses one of the key concerns faced by parties when structuring secured and/or structured financing transactions in that it explicitly states that the transfer of mortgages in the secondary market shall be exempted from registration fees in the real property registration system will be implemented in practice soon and provide the relative taxation relief needed to push forward securitizations. In addition, the law provides the Council of Ministers with the ability to grant tax incentives for securities issued with respect to real estate financing.

In certain jurisdictions registration and transfer fees are payable that also need to be factored into the transaction cost. For instance in Dubai, the Dubai Land Department imposes a 4% transfer fee on transfer and registration of properties. Depending on the value of the transaction such costs can be substantial and prohibitive in respect of undertaking such transactions. In the Tamweel 2012 transaction the transfer fee was key and needed to be discussed between Tamweel and the Dubai Land Department.

Governing Law

In the UAE, Dubai Law No. 16 of 2011 was enacted and amended the jurisdictional basis of the DIFC Courts widening the DIFC Court’s jurisdiction by omitting the requirement for claimants to establish a direct nexus to the DIFC. The benefit of this is that parties could chose to have the documents governed by DIFC law (which are modelled closely on international standards and principles of common law and tailored to the region’s unique needs) as opposed to the laws of Dubai which are based on civil law. Whilst in the Tamweel 2012 transaction, parties chose DIFC courts as the governing law, in respect of the relevant purchase agreements the documents were required to be governed by the laws of Dubai, and where applicable the federal laws of the UAE. The reason for the choice of law was due to the fact that as the assets where based in Dubai, the laws of any sale and transfer of these assets would need to adhere to the real estate law of Dubai.

The laws of Saudi Arabia require the sale of receivables to be governed by the same law as the law governing the receivables themselves, as the Saudi courts and other adjudicatory authorities do not traditionally recognize the choice of foreign law regardless of whether the sale contract or the receivables themselves are governed by foreign law.

Real Estate Law of the Country

In the Tamweel 2012 transaction the pool of assets comprised (i) registered properties whereby prior the issue date the ownership title has been registered at the Dubai Land Department in the name of Tamweel; and (ii) unregistered properties whereby on the issue date, Tamweel was entitled to have its ownership title registered at the Dubai Land Department but such registration was pending. As some of the properties where unregistered, the transaction had to structured such that a portion of the purchase price payable in respect of such unregistered properties would be held in the escrow account pursuant to the escrow agreement. Once properties become registered at the Dubai Land

Department then amounts would be released from the escrow account to Tamweel accordingly. This meant that the securitization vehicle took on continuing obligations as lessor under the residential leases, requiring tailored procedures to allow for this.

This transaction also tested Dubai’s property law. There were features of local law and practice not appear- ing in conventional mortgage loans which had to be considered, including thousands of existing and future post-dated lease payment cheques and rent-control regulations. In addition, because the assets were dirham-denominated while the notes were US dollar-denominated, currency swap arrangements appropriate for a Shari’a-compliant institution had to be introduced.

Other Issues

There is comparatively scarce historical data on defaults which hinders reliable estimates for recovery rates used in pricing and rating trenched products. In the Tamweel 2012 transaction, this lead to the rating agency using very conservative assumptions when assessing the risks related to the transaction.

Innovations in Structuring

Dual SPV Structures

One of the biggest hurdles participants face when securitizing assets in the GCC are those linked with foreign ownership restrictions or enforceability of the rights and obligations pertaining to those assets. The use of dual SPV structures to overcome such issues is common in the GCC.

Many laws within the GCC prohibit a non GCC entity from buying or leasing assets, or impose thresholds on amounts a foreigner can hold. In addition a special purpose company domiciled in Saudi Arabia is not bankruptcy remote and cannot issue securities. Accordingly, many structures require dual entities with funding agreements between the on-shore special purpose company and the offshore special purposes issuing vehicle.

The Sun Finance transaction involved a dual SPV structure whereby Sorouh transferred the land and assigned the scheduled instalment payments owed by sub-developers and all the associated rights under the contracts to Sorouh Abu Dhabi Real Estate LLC (PropCo), a company incorporated in Abu Dhabi, to act as mudarib of the mudaraba and so as to isolate the pool of assets from Sorouh. The Issuer then extended an inter-company loan to PropCo which in turn created security interests over all of its assets in favour of the local Security Trustee acting on behalf of the Issuer.

The securitization market in the UAE is in its very early stages, as a result of this, most securitizations are facilitated via the DIFC where the security laws are fairly comprehensive and developed. The Law of Security (DIFC Law 8 of 2005, as amended), the Real Property Law (DIFC Law 4 of 2007), which specifically covers mortgages over land, and the DIFC Security Regulations are the applicable DIFC laws which safeguard security under a securitization utilizing a DIFC special purpose vehicle. Take for instance the attempted Tam- weel securitization in 2012 which entailed a true sale of assets under the laws of Dubai. In this transaction a special purpose company was established in the DIFC to purchase the properties (and ancillary rights and benefits derived from these assets) from Tamweel so that investors could utilize DIFC’s security enforcement regime and court system. Specifically, the issue price was to be applied towards the purchase of the Properties (in the first instance to TRL in respect of properties registered by the Dubai Land Department, and in the second instance in respect of unregistered properties with any amounts applied towards such unregistered properties into an escrow account). Pursuant to the Purchase Agreement between TRL and Tamweel, Tamweel agreed to sell the legal ownership title to the Properties and assign and transfer to TRL, as its successor in title in respect of such Properties, the Lease Assets and Ancillary Assets relating thereto.

TRL would act as title agent for and on behalf of the Issuer. Legal title to the properties will remain in the name the TRL as title agent for and on behalf the Issuer and pursuant to a declaration of trust, TRL would declare a trust in favor of the Issuer over the legal ownership title to the properties.

Tranching and Overcollateralization

There is a discord between scholars as to what is acceptable in terms of collateralization and reserves which need to be implemented within the limits of Shari’a compliance. If the issuer acts as residual claimant and maintains undistributed cash flows generated from securitized assets as excess amounts, the transaction could potentially not qualify as a complete pass-through structure and could be viewed as contrary to Shari’a principles. Participants are utilizing the Islamic structure of musawama which is a sale arrangement where the price of the sale is negotiated between the parties (without any reference to the original price paid by the seller) to structure trenching into the transactions. Sun Finance was the first transaction which utilized this structure to achieve Shari’a-compliant trenching.

So Why Securities

According to a report published by Standard & Poor’s in November 2011 “there is a large amount of regional debt maturing between 2012 and 2014 will add to the refinancing risk facing issues in the [GCC] countries”. The report continues with estimates of approximately US$35 billion worth of debt maturing in 2014.

Generally, sukuk issuances are increasing with a report by Standard and Poor’s in March 2013 stating that “… while still considered an alternative investment, Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services believes sukuk have the potential to grow and join the mainstream. Funding needs and large infrastructure investments… in the GCC, combined with better global investor sentiment, are behind today’s momentum in the sukuk market.” The report continues with the fact that “yields in the region have been declining, and even fell under those on conventional debt. Add to that strong domestic appetite for Islamic finance and sound liquidity, as well as greater political willingness to move ahead with sizable infrastructure projects. We believe that a number of banks, particularly, will come to market, needing to re-finance their existing debt and seeking larger amounts to match the credit needs of their corporate clients, especially in project finance”.

Much of the anticipated infrastructure developments and financial institutions financing requirements (which are currently met by short-term financing products) will require longer-term financing. Securitization, which in its very nature is structured around long term debt, will provide another form of long term liquidity and a relatively low cost of funding. In addition, Islamic securitizations are asset-backed, which means Islamic finance is particularly suited to securitization as many structures are based on underlying assets.

Furthermore, the development of the legal infrastructure (particularly in Saudi Arabia) may make securitization a viable source of long-term financing to borrowers. The potential is great but what we need to see are industry players pushing and seeing through securitization with internal credit teams gaining a better understanding of these structured products.