Introduction

The capital markets of the GCC countries and the wider Middle East region trace their roots back to the 1970s when the region experienced its first oil boom. The capital markets in most Middle Eastern countries were largely underdeveloped until the early 1980s. However, rapid economic expansion due to high oil prices and massive privatization plans in countries such as Egypt and Turkey led to the establishment of a number of large corporations and joint stock banks. This prompted authorities to regulate and develop capital markets to fund the growth of these corporations. For instance, in Saudi Arabia, a Ministerial Committee was formed composed of the Ministry of Finance and National Economy, Ministry of Commerce, and Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency (SAMA), to regulate and develop the capital markets. Consequently, by mid-1980’s, most of the GCC countries had equity markets with formal secondary trading facilities. This, coupled with rising government financing to fund diversification programs, paved the way for the government bond market. However, the market for trading of debt instruments is still in its early stages.

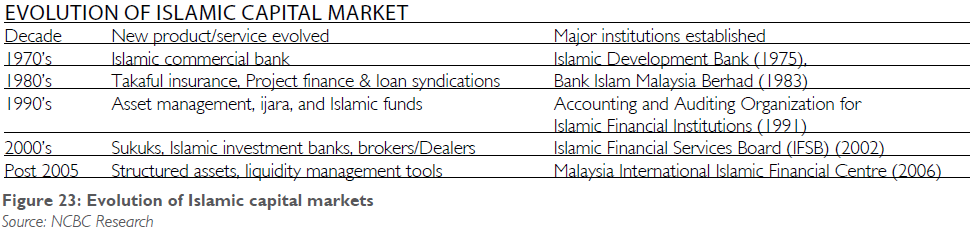

Equity markets in the GCC and most Middle Eastern countries were characterized by a lack of liquidity until the early 2000’s. As rising incomes induced greater retail participation, and as the number of listed stocks with a higher proportion of free-float increased, volumes and liquidity emerged in these markets. However, the debt markets remain illiquid due to the small magnitude of outstanding issuances across the maturity spectrum, limited investor interest and underdeveloped trading facilities. Greater institutionalization, domestic and foreign, will further deepen capital markets in the region. Realizing the importance of foreign capital to reinvig- orate capital markets and fund economic growth, governments in the GCC and Middle East gradually have opened up their stock markets to foreign investors and relaxed repatriation regulations over the past five years. Against this backdrop, the emergence of Shari’a-compliant finance as a distinct segment of financial services is a relatively recent phenomenon gaining traction post-2000 despite a long and august history of Islamic jurisprudence. The evolution of the Islamic finance industry began with a few pioneering institutions such as DIB that offered products and services during the 1970’s that helped depositors and borrowers abstain from the use of riba (roughly interest/usury, money earning a return on itself without the provision of any service).

The 1980’s can be broadly characterized as ‘institutionalization’ of the Islamic finance industry with the introduction of formal regulations in a growing number of countries. For instance, in 1981, all domestic commercial banks in Pakistan were allowed to accept deposits on profit/loss sharing basis. Malaysia opened Bank Islam Malaysia, its first official Shari’a-compliant bank, in 1983. The concept of Islamic finance was formalized during the 1990s with the establishment of Indonesia’s first government-sponsored Islamic bank, Bank Muamalat in 1991. Furthermore, institutes, such as the Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI), were developed to address issues relating to accounting standards that appropriately reflected the nature of Islamic financial transactions.

Islamic capital market in Malaysia

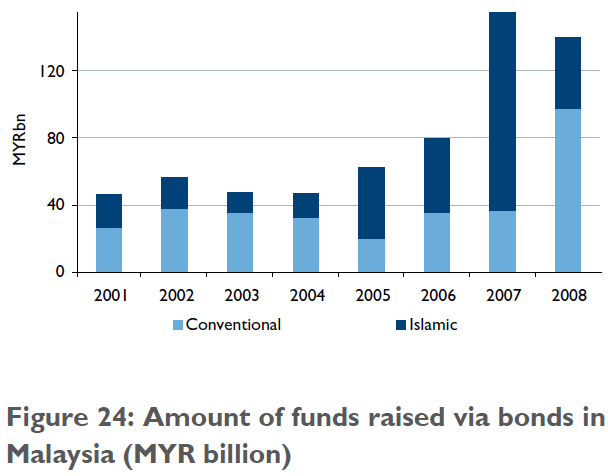

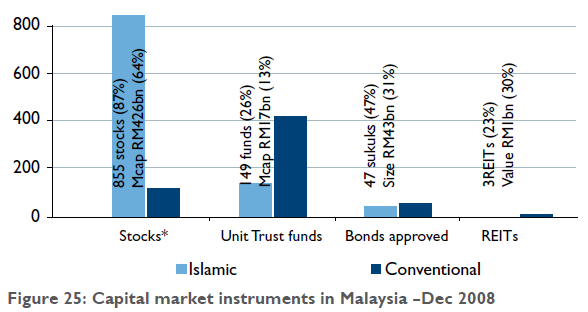

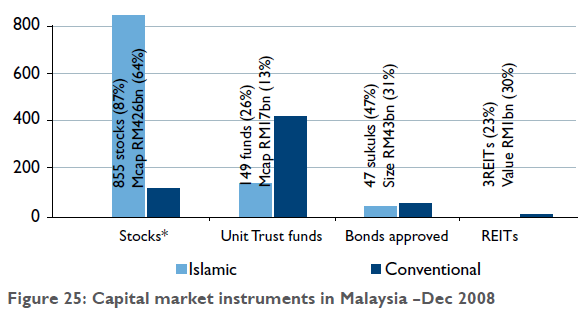

Malaysia has played a pioneering role in the development of Islamic finance, with concerted efforts made by the government, the central bank, regulators and market players. Over the past 30 years the country has built a strong and comprehensive framework for Shari’a-compliant banking and finance and has inspired other Muslim countries to emulate its initiatives. For instance, the nation’s Islamic Banking Act and the Takaful Act were created in 1983 and 1984 respectively. An emphasis on innovation has culminated in the development of several Islamic products, including sukuks, equities, unit trusts and exchange-traded funds (ETFs). In addition, guidelines for best practices in the Islamic stock-broking business have been defined. At the end of 2008, the Shari’a-compliant fund management industry in Malaysia had grown from just two Shari’a-based unit trust funds in 1993 to 149 in 2008 (26% of the total 579 funds), with a net asset value of MYR17.19 billion (US$ 5.261 billion). Furthermore, at the end of 2008, 87% of all securities listed on Bursa Malaysia were Shari’a-compliant, accounting for 64% of the total market capitalization.

Malaysia has also been at the centre of sukuk origination over the years. The contribution of sukuk issuance to total funds mobilized via bonds surged from 42% in 2001 to 77% in 2007. Though the economic downturn impacted the value of sukuk issuances in 2008, sukuks formed 47% of all bonds (in terms of numbers) approved by the Securities Commission of Malaysia Malaysia has a well-developed Shari’a-based legal governance system along with a Shari’a-Advisory-Council (SAC), which advises on issues related to Islamic finance and is the approving authority for Islamic products. Apart from the regulatory infrastructure, liberalization and a favourable tax environment have also contributed to the growth of the Islamic finance industry in Malaysia. Post-liberalization, foreign equity ownership rules have been relaxed and Islamic financial management companies are permitted 100% foreign ownership.

The initial efforts to remove anomalies and provide similar tax treatment for Islamic and conventional capital market transactions were taken in the Federal Budget 2004. The Malaysian government also introduced ten-year tax exemption for Islamic banks and takaful operators on income from business conducted in international currencies. Today, Malaysia’s contribution to the development of the Islamic finance industry has received global recognition. Malaysia continues to focus on product innovation, human capital development and increasing awareness of Islamic financial products.

Rising popularity in non-Muslim countries

Islamic capital markets have seen growing interest from non-Muslim investors in Islamic products. These products, while offering an opportunity to diversify portfolios, tended to be relatively simple, transparent and low-risk. The recent credit crisis has also led to a shift in investor preference toward ‘safe haven’ investment products. While the economic crisis has called for better regulatory norms, Islamic financial institutions were relatively safeguarded as Shari’a law does not approve speculation, believed to be the underlying cause of the current crisis. Consequently, the global crisis has increased awareness of Islamic finance in markets across the world.

Central banks and government authorities in several non-Muslim countries, including the United Kingdom Germany, Spain, Malta and Italy are exploring the regulatory and legal aspects of Islamic finance products. France, with the largest Muslim population in Europe, is currently changing its legal system and establishing an infrastructure that is conducive to Islamic finance to al- low Islamic financial institutions to provide services to its 5 million-strong Muslim population and to attract investments from the Middle East. The first Islamic bank in France with EUR40 million capital is likely to be licensed by the end of 2010. As a result of these efforts, a French financial institution plans to raise EUR1.0 billion through a sukuk issue in 2009, marking the first issuance of Islamic corporate debt in Europe. Buoyed by the French government’s efforts to boost Islamic finance, it is likely that an increasing number of French companies would consider Islamic debt securities as an alternate instrument for mobilizing funds.

Even the UK government planned a sovereign sukuk issuance in 2008, although it called this off later, citing poor market conditions. The number of licensed Islamic banks in the UK has doubled to 23 in the past two years. Furthermore, the UK government, in its efforts to portray London as the European hub for Islamic finance, has already made some tax and regulatory changes such as removal of the additional stamp duty on Islamic mortgages to ensure tax neutrality between Islamic and conventional financial products. To this end, various international banks have opened their Islamic finance windows in the country. Apart from these, six Islamic banks, one takaful insurance provider and one Islamic hedge fund manager have been authorized by the Financial Services Authority (FSA) to operate in the country. Historically, Islamic finance services have been offered through specialty banks that exclusively provided Shari’a-compliant products (for instance, Al Rajhi Bank in Saudi Arabia). However, with the increasing popularity of Islamic finance among non-Muslim countries, large banks in Western countries have started offering Islamic finance products through a separate Islamic window. For instance, HSBC established its separate Islamic finance entity, HSBC Amanah, in 1998. UBS also set up a standalone bank in Dubai in 2004 to provide Islamic finances services to Middle Eastern clients. With Shari’a-based products gaining favour with investors and governments in non-Muslim countries, we believe Islamic fi- nance will constitute an integral part of the international financial system in the coming years.

Global emerging markets – rebalancing the global economy

The global financial events of the last two years have demonstrated that emerging markets can prevail when confronted with the ultimate stress test – a widespread crisis caused by dislocations in the developed world as opposed to their own solvency issues.

Despite the subsequent withdrawal of capital that ultimately put pressure on emerging market asset prices, many emerging market economies entered this downturn in a position of financial strength – born of conservative leverage and sound policies.

With lower leverage, transparency and no speculation as the tenets of Islamic finance, risk-averse emerging market companies should appeal to the increasingly global Islamic investment community. Yet the involvement of Islamic investors in global emerging markets is still nascent and represents an outstanding growth opportunity for both asset gatherers and investor returns.

Rebalance in progress

The global economy is rebalancing and emerging markets are at the heart. The last two decades saw a cycle in which emerging markets were dependent on Western consumption. As a seemingly strange result, the emerging world became creditors to the West and actually financed western deficits, prolonging the cycle and allow- ing the West to continue consuming beyond its means. The credit crunch of 2007-2008 has likely damaged this cycle. The Western consumer will retrench to reduce their household debt. Going forward, emerging market economies are going to be driven more by domestic growth at home and trade with other developing nations, rather than exports to the West. An economic decoupling of sorts.

An economic decoupling does not mean total divorce from the global business cycle. It means that developing countries’ gross domestic product (GDP) growth will slow much less than in previous business cycles, yet still be far superior to the GDP growth in the West. This is already happening – against a backdrop of anaemic growth in 2009/2010 in the West, most of the larger developing nations will show GDP growth in the range of 3-6%, with China looking at 8-9%.

Exports to the West have declined, but in many cases have been replaced with booming export growth to other emerging nations. China is now the biggest buyer of Brazil’s exports and, in turn, some 50% of China’s exports now go to other emerging markets. In 2008, domestic demand and investment actually accelerated in some emerging nations.

The rise of emerging economies

History provides perspective on this rebalance. In 1820, today’s emerging economies accounted for more than 80% of global GDP. With the onset of the industrial revolution, these countries turned inward and ultimately lost their leadership position in the global economy. But, in recent times, emerging markets have re-emerged to regain – from their perspective – their rightful place in the economic world. Today, they account for more than 50% of global GDP, up from 38% in 1950, and are rapidly expanding their share.

Numerous factors have contributed to the revival of these countries, including:

- their ability to outsource to lower-cost economies in Asia,

- their acceptance into the World Trade Organisation,

- strong commodities cycles,

- favourable demographics,

- their implementation of conservative fiscal and independent monetary policies and

- the resulting price stability and falling interest rates supporting domestic investments and consumption.

The number of people joining the working population – a key driver of long-term growth potential – is six times higher in emerging economies than that of developed markets. The demographics of these nations are incredibly favourable to support underlying growth. Millions of new young consumers are entering the market, aspiring to housing, transport, communications and discretionary spending.

If China continues at its current GDP growth rate of 9%, its economy will double in size in seven years to US$ 10 trillion. The United States is a US$ 14 trillion economy. It is difficult to forecast this tremendous speed of growth for Western economies that are weighted down with trillions of dollars of leverage. Therefore, one must question why many investors have a greater allocation to the US compared with China.

Today, non-developed economies account for 85% of the global population, 75% of global land mass, 70% of global foreign exchange reserves and 50% share (and growing) of global GDP. Yet “emerging market equities” as an asset class still only represent some 15% of world equity indices.

Invested on a GDP-weighted asset allocation benchmark, most investors would be very underweight emerging markets, but even investing against the 15% weight in an ACWI/World market capitalization benchmark, global investors are still underweight this benchmark (source EPFR global).

A compelling asset class

To capture the long-term rebalancing of the world economy, it would be beneficial for Islamic investors to consider the emerging market equity asset class as a component of their portfolio. Not only do emerging markets provide access to faster growth with strong fundamental underpinnings, but they also offer a wide opportunity set spanning 20 countries. For Islamic investors based in the Middle East, emerging markets offer a different opportunity set than their core GCC markets. With correlations across all asset classes having tightened in recent years, it’s difficult to argue that emerging horizon) and offer pure diversification away from other markets. But fundamentals drive markets on a medium-term time horizon and it is believed that from here, emerging markets fundamentals look a whole lot better than those of the developed markets.

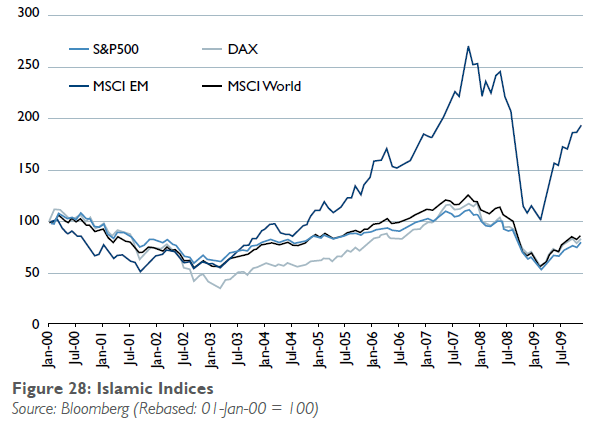

In the last decade, there has been underlying secular improvement in developing economies as reflected in the doubling of the MSCI Emerging Market Index (up 90% since 1998), compared to a fall of 35% in the S&P500 Index over the same period. Driving this trend is a combination of fast economic growth, but more importantly, an improvement in emerging corporate return on equity. So, it’s not just about headline GDP growth, it’s about profitable growth.

Growth without profitability has no value to an investor. During the 1990s, emerging markets corporations destroyed value by failing to cover their cost of capital. The changes they have made improved profitability to match and exceed levels in the developed world. We expect them to maintain a trend increase. What’s more, as we’ve seen, profitability is not built on the shifting sands of excess leverage. It comes from margins and efficiency.

Twenty-five years ago, a dollar invested in the developed world would have made a 300% gain over 25 years. A dollar in the emerging world, despite the Asian crisis and the worst financial crisis for 70 years, would have returned 2000%. The question is therefore, can this outperformance continue? The belief by emerging fund management experts Rexiter Capital Management is that it can. Fund Manager and Head of Global Emerging Markets Shari’a Strategy, Nicholas Payne purports, “The key variable here is leverage… or rather lack of it. Times of stress within emerging markets have been associated with ex- cess leverage such as the Asian crisis, but the picture looks very different today.”

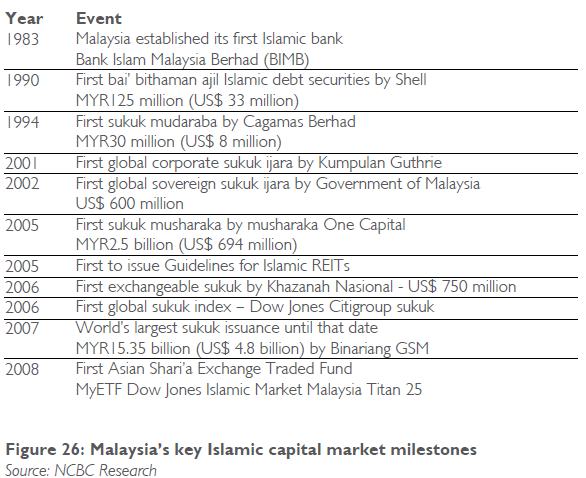

Figure 27 is a UBS stress indicator index looking at net external debt ratios, fiscal deficits and credit as a percentage of GDP. The higher the number, the greater

the level of financial stress in the countries. The “stress” level for emerging markets in the late 80s and 90s when emerging markets went on a borrowing binge resulted in the Asian crisis of 1997-1999. A remarkable catharsis brought about sounder management, cleaned up banking systems and debt write-downs. The path of developed markets now illustrates a very different and deteriorating direction. The gap between developed and emerging markets has never been so wide. This discipline has allowed emerging market sovereigns to weather the recent crisis in a much better way than developed counterparts, allowing them to enact counter-cyclical fiscal policy and avoid having to resort to printing money. At the corporate level, corporate gearing at some 30% of equity, is now down to a level for overall emerging that should be much more interesting for Shari’a investors. Emerging markets’ profits look like they have a sound basis off which to expand in the coming years. Though the underlying secular trends that have driven the out-performance of emerging economies in recent years may have been stressed, they have not been broken. Emerging markets as an asset class offers untapped potential, given the continued growth of developing nations. It’s a compelling asset class that is aligned with Shari’a-compliant investing.

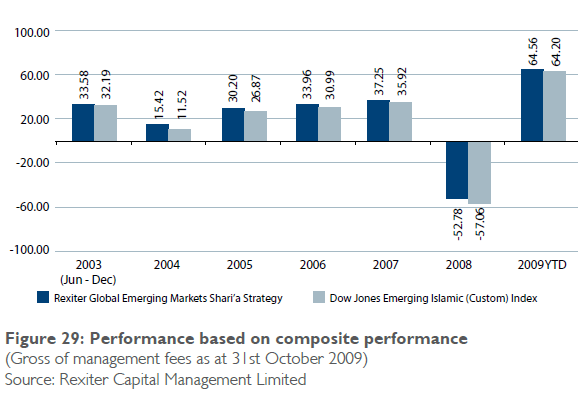

Rexiter’s position is that emerging markets have out-performed developed markets and should continue to do so going forward. Their belief is that global investors (including Islamic investors) are underweight in this asset class and should consider increasing their exposure. In the inefficient asset class of emerging markets, an active manager should be able to add alpha, something Rex- iter has achieved with its Shari’a strategy for six straight years as illustrated below.

Use of sukuk in Islamic countries remains buoyant

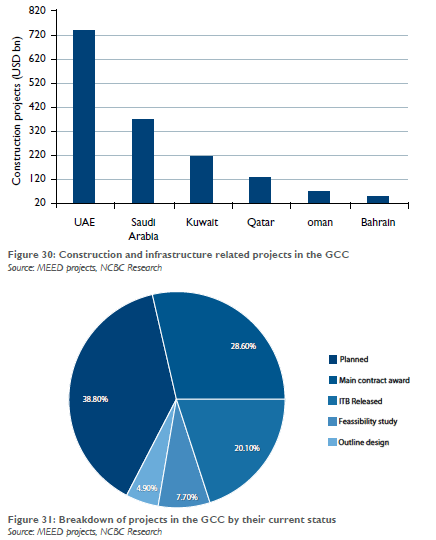

Besides gaining a foothold in non-Muslim countries, the Islamic finance industry has also evolved in product sophistication and offerings, with structured bond products and asset management services becoming widespread. Among all the Islamic capital market products, sukuks have been the most popular, especially in emerging economies. This can be attributed to the ever-growing need of governments to fund infrastructure and construction-related projects in these countries. The Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) -to- GDP ratio in the GCC and other Islamic countries such as Indonesia and Malaysia averaged 20-24%, well below India (33%) and China (41%). Hence, the governments of these countries are committing huge sums for infrastructure development. Projects worth US$ 2 trillion are in various stages of planning or completion across the GCC. More than 70% of these are construction and infrastructure-related. The problem of funding infrastructure and construction projects in emerging countries is compounded by the less developed nature of the conventional capital market. Consequently, governments in these countries are increasingly relying on alternate products such as sukuks to meet their financing needs.

Another factor driving the popularity of sukuks among Islamic capital market products is that sukuks are backed by physical collateral. According to Ernst & Young, sukuk issuances are likely to rise to US$ 27.5 billion in 2009, up from US$ 15 billion in 2008.

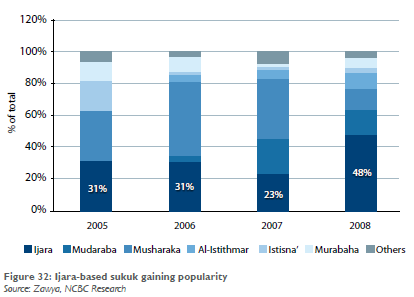

The structure of sukuks also plays an important role as most prospective investors prefer sukuks that are Shari’a compliant and less complex. In the past two years, the sukuk market has been witnessing an increasing Mpreference for ijara based sukuk issuances over murahaba issuances. This is primarily due to AAOIFI’s 2007 ruling, which held that most murahaba sukuks do not comply with Shari’a principles. Furthermore, the secondary trading of murahaba sukuk is not permissible. This, in turn, causes liquidity problems. The rising popularity of ijara based sukuks is evident from the fact That around 48% of all sukuk issuances during 2008 in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region were ijara based, compared with 23% in 2007 and 31% in 2006.

Islamic capital markets outperformed conventional markets during the crisis

The current financial crisis has also impacted Islamic capital markets because of strong linkages with the global financial system. Moreover, the performance of Islamic institutions depends on their exposure to underlying as- sets such as real estate and energy, which have both corrected during the crisis. Most Islamic financial transactions are still referenced to London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR), exposing them to economic risk, despite their imperviousness to certain interest rate risks due to prohibition of speculation on interest rate movements,which impacts their profitability.

However, in the past few years, the Islamic capital market seems to have performed well in terms of returns, compared with conventional markets and has weathered the current financial crisis relatively better. This is attributed to the inherent ethical and non-speculative nature of the market. This reflects in the prohibition of riba, gharar, maysir, and haram activities, providing an inherent security mechanism to the Islamic financial services sector. Islamic financial institutions, unlike conventional institutions, do not have to deal with issues such as speculation or overvaluation. Moreover, they could not invest in structured mortgage products such as Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs) due to non-compliance of these instruments with Shari’a law. Consequently, Islamic institutions had no exposure to the subprime crisis and thus were less adversely impacted by it.

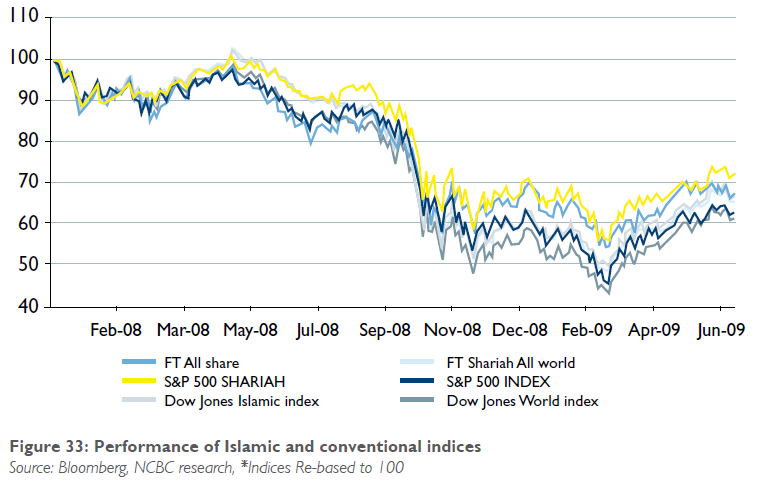

For instance, GCC-based Shari’a funds fell 21.7% during the past one year, compared with the 26.4% decline in conventional funds. This vindicates the fact that Islamic funds weathered the global financial crisis relatively better than conventional funds. This also reflects in the 28% fall in the S&P Shari’a index between 1 January 2008 and 19 June 2009 compared with the 37% decline in the S&P 500 index during the same period. Though the indices for both Islamic finance and conventional systems recorded negative returns during 4Q-08 and early 2009, the quantum of losses recorded by Islamic indices or products was lower. Consequently, Islamic financial in- struments are attracting the attention of both Islamic and non-Islamic investors globally.

Challenges to development of Islamic capital market

Though the Islamic capital market is growing fast, it remains a niche market with several practical and regulatory issues. The major challenges are:

- Difference in Shari’a interpretation

Shari’a scholars, with complete understanding of the Shari’a law play a key role in ensuring proper interpretation of Islamic principles. Legal complexities arise, particularly in non-Islamic countries, as the transaction arrangement needs to comply with commercial aspects in addition to the Islamic law. However, due to various Islamic schools of thought, interpretations and understanding of the law may differ between Shari’a scholars. Some terms that might be acceptable to scholars from one school of Islamic jurisprudence, may not be valid for another. Therefore, convergence of Shari’a principles and interpretations are important to ensure investor confidence globally. While continuous interaction among Shari’a scholars can help overcome this issue, the dearth of such experts is a critical deterrent.

- Inadequate regulatory framework

The rapid development and innovation in the Islamic financial services industry has not been matched with the setting up of an adequate and uniform regulatory framework. Current regulatory frameworks for Islamic financial services vary across different countries. There is still ambiguity on whether Islamic banks should be treated as standalone entities or under the conventional banking system. Furthermore, there is still uncertainty regarding accounting standards to be followed ranging from International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), International Accounting Standards (IAS), AAOIFI standards or Malaysian Accounting Standards. Regulators are required to constantly keep themselves abreast with new market developments, focusing on ensuring adequate and timely supervision of the market. While the regulatory framework for conventional instruments may be adapted for Islamic products, certain transactions may require more specific guidelines to ensure Shari’a compliance and regulation.

- Lack of standardization and presence of numerous Shari’a committees

Standardization is a highly challenging but crucial issue in accounting (standard accounting practices) and regulation (on the lines of BASEL committee). Currently, various jurisdictions have their individual monitoring Shari’a committees and regulatory approaches. Since there are very few collaborative efforts on the regulatory front at the international level, there is no uniform approach for monitoring and enforcement of securities laws. Due to lack of standardization and cooperation among different Shari’a committees, market players have to go through an approval process that is lengthy, which defers the development of new products considerably. This critical gap in regulatory measures has created an urgent need for cross-border cooperation to ensure uniformity in regulations and product structure. While uniformity would boost product understanding in cross-border investors, authorities will be able to complement each other’s efforts through enhanced cooperation. Moreover, standardization would spare the need for an approval process for examining the structural robustness of widely-used products. This would reduce the time and money spent on repetitive processes, thereby enhancing cost efficiency.

- Need for liquidity and risk management

Islamic institutions are more susceptible to asset side risk on their balance sheets compared with conventional institutions, as they provide loans through profit and loss sharing agreement (PLS). Loans provided under PLS agreements are more vulnerable to market and credit risk as the lender would be able to recover the loan amount only if the borrower makes a profit. Furthermore, Shari’a law restricts use of cash collaterals, which, in turn, exposes lenders to a much riskier environment compared with fixed-interest rates loans. Islamic financial institutions are also exposed to a major risk of asset-liability mismatch. Due to the lack of a mature Islamic interbank market, Islamic financial institutions face difficulties in efficiently managing their day-to-day cash and short-term liquidity needs.

Several Islamic institutions, including AAOIFI, IIFM and IFSB, are currently focusing on human capital development, standardization of products and practices and developing a framework for monitoring and regulatory purposes to strengthen the Islamic financial system.

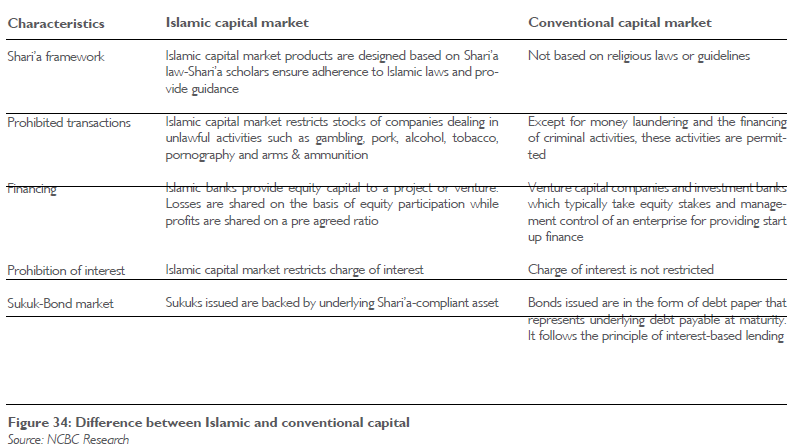

Difference between Islamic and conventional capital markets

The underlying principle of Shari’a forms the basis of difference between Islamic capital markets and conventional capital markets. Broadly, according to the Shari’a dictum, conventional transactions are permissible if the prohibited elements are removed from them. Unlike conventional capital markets, Islamic capital markets are ideally characterized by the absence of interest-based transactions (riba), doubtful transactions and stocks of companies dealing in unlawful activities (haram) or items. It should also be free from any form of unethical or immoral transactions, such as market manipulations, insider trading, short selling, and even excessive exposure of one’s financial position by contra deals that can- not be backed by sufficient funds. The core differences in the Islamic capital market vis-à-vis conventional capital markets can be summarized as follows:

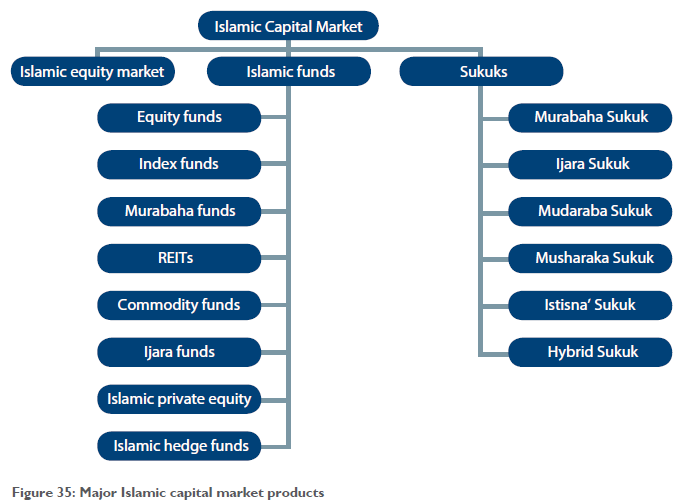

Types of Islamic capital market instruments

The following are the broad categories of several Islamic capital market instruments that are available to meet the needs of investors, Islamic banks and insurance companies: