INTRODUCTION

The past two decades have witnessed a substantial increase in the number of IBFIs in different parts of the world. Even if IBFIs’ sizes are relatively small compared to international standards, it has to be noted that the prospects for growth and expansion in both Muslim and non-Muslim countries are strong. As far as principles, Islamic banking has the same purpose as conventional banking except that it operates in accordance with the rules of Shari’a.

It was to meet the demand for Islamic financial services and capture the emerging market around them that conventional banks started opening Islamic windows and Islamic units for those clients who did not want to indulge in interest-based transactions. This conviction created an increased demand for Islamic products in the field of financing and gave birth to a market where only Islamic products are acceptable. Thus, banks working under Islamic windows are established to provide an additional service to Muslim clients or to offer a variety of products for general clientele. Despite the fact that most of Islamic banks are within emerging Middle Eastern countries, many universal banks in developed countries have begun to valve the massive demand of Islamic financial products.

The basic principles of IBFIs have protected them from the global financial crisis. Indeed, it is broadly known that Islamic banks perform better than conventional banks during financial crises. One key difference is that the former don’t allow investing in and financing the kind of instruments that have adversely affected their conventional competitors and triggered the global financial crisis. These instruments include mainly derivatives and toxic assets. When we compare Islamic banks to conventional ones, we are not comparing one financial institution to another as many analysts like to put it. We are rather comparing two different genres. Under Islamic finance, greed, exploitation and abuses are at minimum. Reasons are attributed to the religious nature of the depositors, the bankers, and the investors, and because of the direct involvement of all the parties in the transaction. No one has any direct or indirect interest in exploiting one another, and if they do, they all fail. In addition, Islamic banks do not finance risky investments, or intangible assets, and they equate the interest of the society to that of the investor.

Academics and policymakers alike point to the advantages of Islamic financial products, as the mismatch of short-term, on-sight demand deposits with long-term uncertain loan contracts is mitigated with equity elements. In addition, Islamic financial products are very attractive for segments of customers who request financial services that are consistent with their religious beliefs.

Despite having undergone considerable developments during the past few decades, empirical evidence on profitability, efficiency and stability of the Islamic banking sector is still in its infancy. Previous literature has compared the profitability of Islamic and conventional banks, using comparative ratio analysis. A myriad of studies have examined the performance of Islamic banks using financial ratios. Several other studies have examined the efficiency of Islamic banks and compared them with conventional banks and Islamic windows operation. Moreover, competitive conditions are likely to affect bank performance and efficiency, in addition to equity capitalization levels.

In fact, several authors have investigated the importance of competitive conditions on bank profitability, distinguishing among Islamic and conventional banks and using a variety of key indicators (traditional concentration measures, the PR-Statistic, and the Lerner index).

Some studies have examined bank-specific factors of profitability (e.g., size, revenue growth, risk, and control of expenses), while cross-country investigations have considered external factors (e.g., inflation, concentration, and GDP growth), in addition to a few internal factors of profitability.

The results from many of these previous studies comparing the performances of Islamic and conventional banks are unsatisfactory for several reasons. First, large proportion of the studies is based on small samples (particularly of Islamic banks). Second, where sample sizes are large, the data have often been collected across a variety of countries with very different economic size. Third, the significance of the differences in performance between the two types of banking is often not tested. Studies have generally employed few financial ratios – mainly return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE) – to examine the performance of the banks. Forth, previous studies do not provide clear answers whether and how the profitability, cost efficiency and stability differ between conventional and Islamic banks. This ambiguity is exacerbated by lack of clarity whether the products of Islamic banks follow Shari’a in form or in content. We therefore turn to empirical analysis to explore differences between the two bank groups.

DATA AND METHODOLOGY

We collect data for 16 countries from banks’ annual reports and financial statements, central banks reports and Bankscope to construct and compare indicators of profitability, efficiency and stability of both the conventional and Islamic banks. We only include banks with at least two observations and countries with data on at least four banks. We restrict our sample to the largest banks in terms of assets within a country so that our sample is not dominated by a specific country. Finally, we eliminate outliers in all the variables by winsorising at the 1st and 99th percentiles.

In our main analysis, we use two different samples, both observed during the period 2006 – 2013.

In Table 1, we present data on 16 countries with both conventional and Islamic banks. Specifically, we present the number of Islamic and total banks observed in our study, as well as the share of Islamic banks’ assets in total banking assets, all for 2013. Further, we report the number of listed banks, for both Islamic and conventional banks.

We use an array of different variables to compare Islamic and conventional banks in term of profitability, efficiency and stability. First, we compare the profitability of conventional and Islamic banks, using two indicators suggested by the corporate finance literature: the ROA and ROE. Second, we use two indicators of bank efficiency. Overhead cost is our first and primary measure of bank efficiency and is computed as total operating costs divided total costs. As alternative efficiency indicator, we use the cost-income ratio, which measures overhead costs relative to gross revenues, with higher ratios indicating lower levels of cost efficiency.

Third, we use two indicators of bank stability. The z-score is a measure of bank stability and indicates the distance from insolvency, combining accounting measures of profitability, leverage and volatility. Z-score indicates the number of standard deviation that a bank’s return on assets has to drop below its expected value before equity is depleted and the bank is insolvent (see Roy, 1952; Hannan and Henwick, 1988; Boyd, Graham and Hewitt, 1993). Thus, a higher z-score indicates that the bank is more stable. Then we use an indicator of maturity matching – the ratio of liquid assets to deposit and short-term funding – to assess the sensitivity to bank runs.

| Number of Banks | Listed Banks | Share of Islamic Banking Assets to Global Islamic Banking Assets in 2013 (expressed in percent)** | |||

| Islamic Banks | Conventional Banks | Islamic Banks | Conventional Banks | ||

| Bahrain | 23 | 19 | 4 | 5 | 2 |

| Qatar | 4 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| Kuwait | 5 | 9 | 5 | 6 | 7.9 |

| UAE | 9 | 11 | 4 | 11 | 8 |

| Saudi Arabia | 6 | 9 | 1 | 8 | 12.2 |

| Egypt | 3 | 32 | 2 | 11 | 2 |

| Jordan | 2 | 11 | 1 | 7 | 1.5 |

| Yemen | 3 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 |

| Tunisia | 2 | 18 | 0 | 10 | 0.2 |

| Syria | 3 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 0.1 |

| Lebanon | 1 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 0.1 |

| Malaysia | 19 | 17 | 0 | 3 | 10 |

| Indonesia | 2 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 1.4 |

| Pakistan | 5 | 11 | 5 | 11 | 1 |

| Turkey | 4 | 26 | 2 | 12 | 3.1 |

| Bangladesh | 6 | 22 | 5 | 22 | 1 |

| Total | 97 | 221 | 33 | 128 | 54.9 |

COMPARISON BETWEEN ISLAMIC AND CONVENTIONAL BANKS

Comparing Islamic and Conventional Banks’ Profitability

Profitability is the most used indicator to evaluate the performance of the business. It reflects how efficient a business’s management is in allocation of available resources to high yields assets in light of a business’s risk profile. Moreover, sustained profitability levels provide a defense against capital loss during hostile economic conditions; therefore protect shareholders’ equities and creditors.

| Islamic Banks (%) | Conventional Banks (%) | ||

| Overall sample | ROA | 2.38 | 1.41 |

| ROE | 12.90 | 14.71 | |

| GCC region | ROA | 3.57 | 1.51 |

| ROE | 12.05 | 12.66 | |

| Non-GCC MENA region | ROA | 1.83 | 1.16 |

| ROE | 14.14 | 12.56 | |

| Non-GCC Asian Countries | ROA | 1.03 | 1.59 |

| ROE | 13.51 | 15.20 |

Table 2 describes the performance of Islamic banks over 2006-2013. In general Islamic banks are more profitable than conventional banks in term of ROA. However, the overall sample of Islamic banks has a lower average of ROE over 2006-2013 than conventional banks.

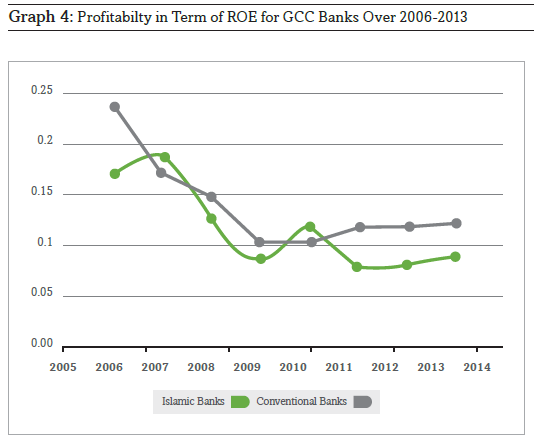

Indeed, as reported in the table below, Islamic banks in MENA and GCC countries are more profitable than conventional counterpart in term of ROA and ROE. However, Islamic banks in the non-GCC Asian countries are less profitable. It seems that the economic conditions and the social environment in their host countries influence the profitability of the concerned banks.

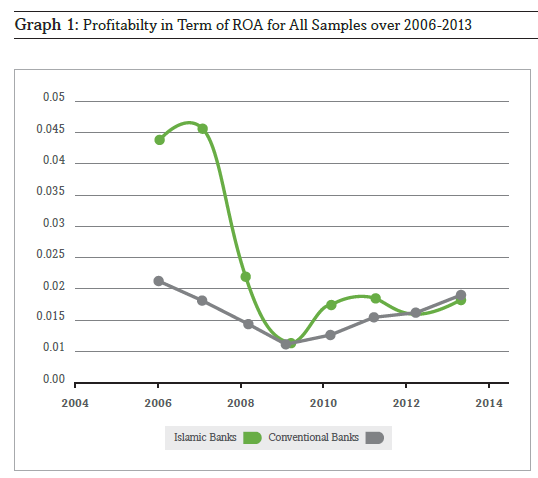

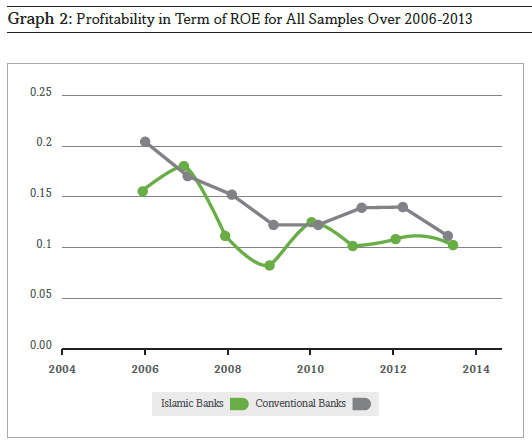

A closer look at the profitability trend over the period 2006-2013, as outlined in Graph 1 and 2, it is evident that Islamic banks have been affected differently than conventional banks before and after the global financial crisis. Graph 1 demonstrates that both conventional and Islamic banks increase their profitability in term of ROA as the market share for Islamic banks increases. During the period 2006-2009, Islamic banks performed much better than their conventional counterparts. Indeed, during the year 2006 and 2007, Islamic banks had reported a significantly high positive growth rate of return on assets as compared to conventional banks. It is worth highlighting two important facts which might have an influence on the assessment of the performance of the two groups of banks. First, the entry of new Islamic banks into the markets constituted the primary underlying reason for the significant growth rate of return of Islamic banks during these two years. The new Islamic banks have shown a strong performance in term of return and profits. Second, over the same period, regulatory authorities and concerned monetary authorities have demonstrated a strong support to the development and the expansion of IBF in the local and international market.

In 2008, in the midst of the global financial crisis, conventional banks suffered considerably, however, Islamic banks continued to witness sustainable growth trend and registered a higher rate of return on assets comparing to their conventional counterparts.

During the period 2009-2013, Islamic banks have a slightly higher ROA than conventional banks. Indeed, conventional banks performing clearly worse than Islamic banks. The former continued to witness a declining trend, while the latter remained generating significant profits.

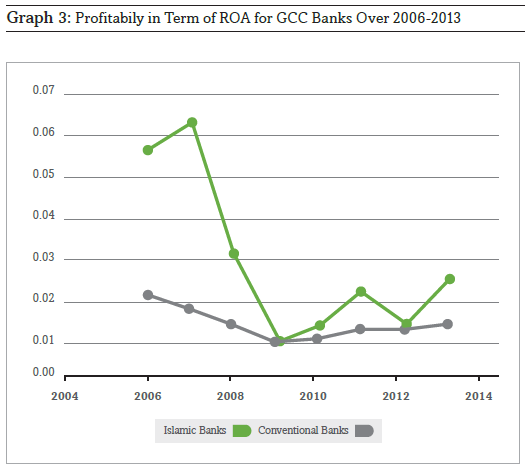

Graph 3 provides evidence that the performance, in term of ROA, of overall Islamic banks is driven by the performance of GCC Islamic banks as both Graphs 1 and 3 show similar fluctuations over the time Nevertheless, it is important to state that the use of ROE may lead to inaccurate results due to size differences between the two samples of banks with regards to credit risk. This may have affected the Islamic banks, as they are smaller than their conventional counterparts. Indeed, conventional banks seem to have come out stronger than Islamic banks in term of ROE as the ROE of conventional banks is higher than that observed for Islamic banks over the period of observation.

Comparing Islamic and Conventional Banks’ Efficiency

The evaluation of efficiency denotes the banks’ overall effectiveness in using its assets to create revenues and control its expenses. A business can be cost-efficient if it can create a relatively high income-generating assets and liabilities for a given level of capital. An efficient bank can generate a relatively high volume of income from its services and intermediation operations with the given level of inputs.

There are many reasons stressing the importance of evaluating of efficiency of Islamic banks. First, an enhancement in cost efficiency means achieving higher profits and increasing the chance of growth and expansion of Shari’a-compliant business in competitive markets and in dual banking systems. Second, clienteles are concerned to know about the price and quality of bank services as well as any new service that banks could offer. This would be influenced by a bank’s overall efficiency of operations. Third, an awareness of efficiency structures is imperative to help policymakers and regulatory authorities to develop new policies that would affect the banking industry.

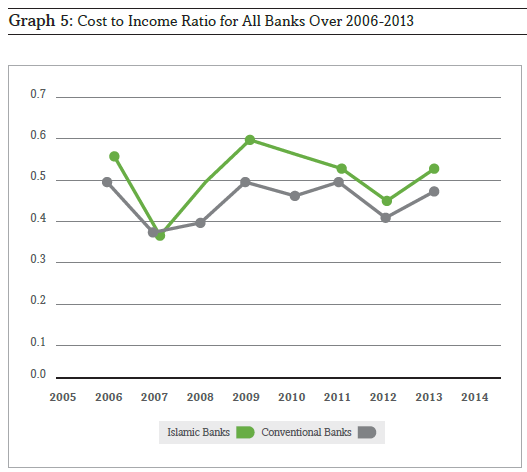

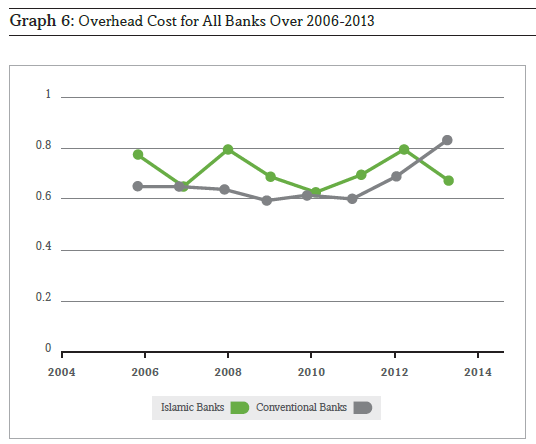

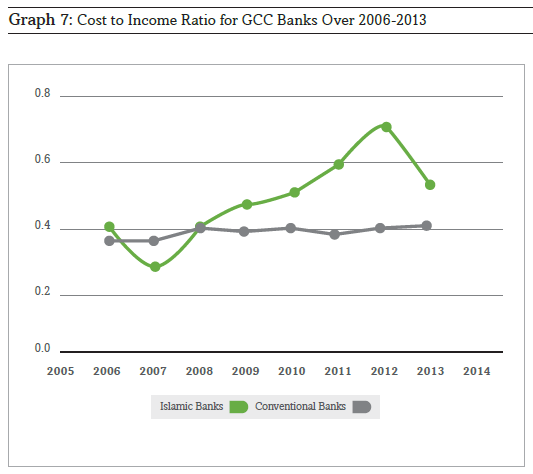

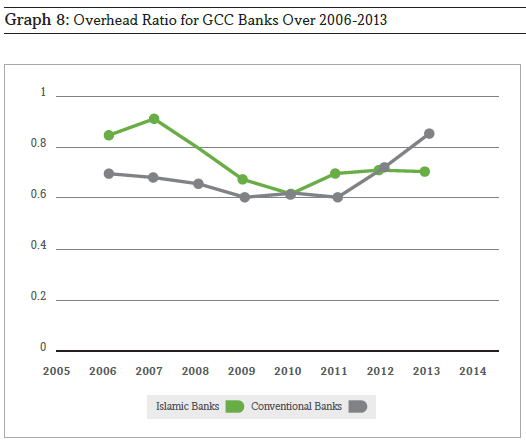

Table 3 reports the average efficiency ratios over 2006-2013. In general, on average, Islamic banks were relatively less efficient compared to their conventional counterparts when we use the cost-to-income ratio as a proxy. Surprisingly, on average, Islamic banks from non-GCC MENA region are relatively more efficient than those in non-GCC Asian countries, and Islamic banks in GCC are less efficient than conventional banks.

As reported in the Graphs 5 and 7, the cost-to-income ratio for Islamic banks increased over the period 2006- 2013, showing that they experienced slight inefficiencies compared to their conventional counterparts.

Many studies have discussed the main reasons of Islamic banks relative inefficiency. Hassan and Hussein (2003) argue that the overall cost inefficiency of the Sudanese Islamic banks was mainly due to technical (managerial-related) rather than allocative (regulatory) factors. Yudistira (2004) demonstrated that the inefficiencies of Islamic banks were related to pure technical inefficiency rather than scale inefficiency.

However, Hassan (2006) showed that the main source of inefficiency was allocative inefficiency rather than technical inefficiency and that the main source of technical inefficiency for Islamic banks was not pure technical inefficiency but scale inefficiency. Sufian (2006, 2007) findings suggested that the scale inefficiency dominated pure technical inefficiency in the Malaysian Islamic banking sector.

Abdul Rahman and Rosman (2013) found that the main source of technical inefficiency among Islamic banks is the scale of their operations. Islamic banks, in general, achieved a high score for pure technical efficiency, indicating that the banks’ management was able to efficiently control costs and use the inputs to

Table 3: Average Efficiency Ratio Over 2006-2013

| Islamic Banks (%) | Conventional Banks (%) | ||

| Overall sample | Cost income Ratio Overhead Costs | 53.27 72.93 | 52.23 67.01 |

| GCC Countries | Cost income Ratio Overhead Costs | 51.09 74.80 | 39.70 71.12 |

| Non-GCC MENA Countries | Cost income Ratio Overhead Costs | 50.30 N/A | 50.95 N/A |

| Non-GCC Asian Countries | Cost income Ratio Overhead Costs | 57.28 70.51 | 57.54 64.31 |

maximize the outputs regardless of scale effects. As well as, the economic conditions of a country seems to be an important determinant of an Islamic bank’s efficiency.

As a second efficiency indicator, we use the overhead ratio, which measures overhead operating expenses relative to total expenses. In general, Islamic banks have slightly larger overhead costs than conventional banks. Beck et al. (2013) explained that more cost-efficient Islamic banking was driven by an overall higher efficiency in countries with both Islamic and conventional banks.

Comparing Islamic and Conventional Banks’ Stability

The stability of the banking sector is the basis of stability of the whole financial system as banks play a fundamental role in the payment system, the financing of investment and principally in the economic growth of the country. Besides, to preserve financial stability, monetary authorities and supervisory authorities are interested to evaluate banking system stability. Banking sector stability is normally reflected by features, such as bank illiquidity and risks relating to it.

Islamic banks have demonstrated a strong resilience during the recent global financial crisis. Indeed, they are prohibited to trade in the collateralized debt obligation market that has been blamed for igniting the current bank crisis particularly among western banks.

The stability of Islamic banking system after the crisis should also be looked into. Table 4 gives a general overview about the stability of Islamic and conventional banks from 2006-2013. On average, Islamic banks have a higher z-score than conventional banks suggesting that the former are more stable and that the latter are more prone to insolvency.

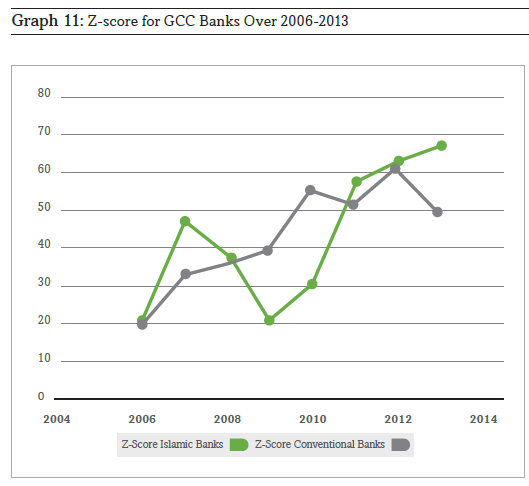

However, Islamic banks in the GCC have on average a lower z-score than the conventional ones, indicating that GCC Islamic banks are more prone to insolvency and financial distress and that conventional banks have a greater stably.

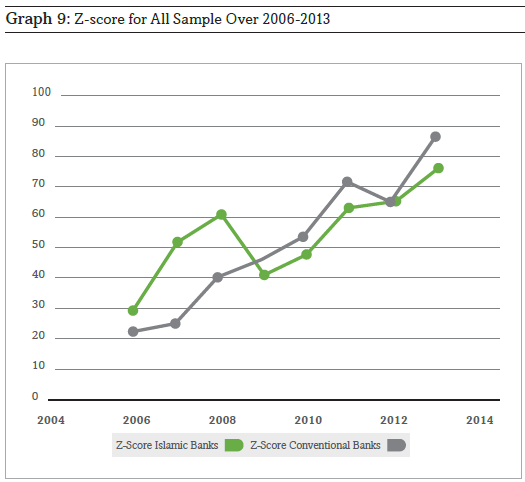

Graph 9 compares the stability, in term of z-score, of both Islamic and conventional banks over 2006-2013. During the period 2006-2009, Islamic banks have a higher z-score than conventional banks. However, over the period 2009-2013, Conventional banks appeared to have recovered and became slightly more stable than Islamic banks.

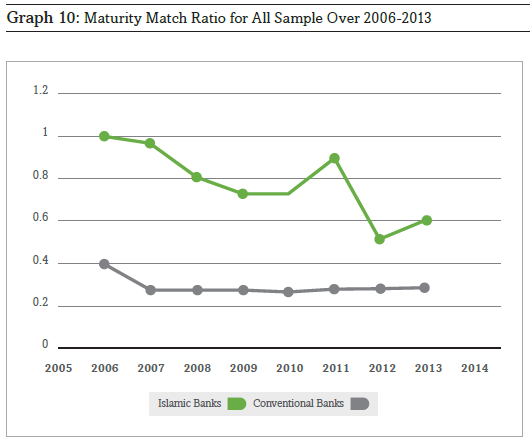

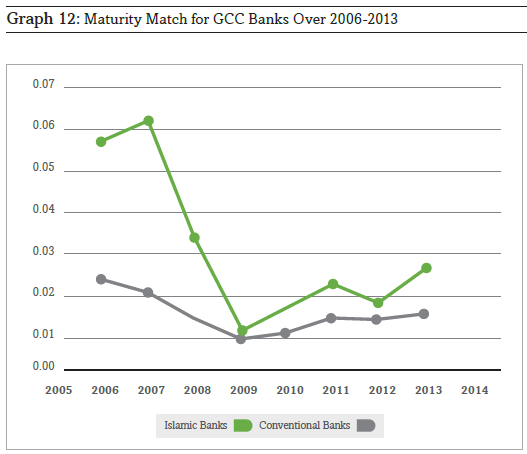

Concerned the maturity match ratio that measure the solvency of the bank, as reported in Table 4, in general, Islamic banks have a lower maturity match ratio than their conventional counterparts. Islamic banks appear less liquid than conventional banks and Graph 10 confirms this. Over the period 2006-2013, Islamic banks have a lower maturity match ratio than their conventional counterparts.

CONCLUSION

Islamic banks seem to be competing well with their conventional counterparts. While the latter have diversified products and are allowed to open Islamic windows in many countries, the former cannot adopt a similar strategy, as the core principle of Islamic finance prohibits them to do so.

In this chapter, we tried to provide clear answers on whether and how the profitability, cost efficiency, and stability differ between conventional and Islamic banks. It is evident that there are few significant differences between Islamic and conventional banks in term of profitability, cost efficiency and stability. Moreover, there

Table 4: Average Stability Ratios 2006-2013

| Islamic Banks (%) | Conventional Banks (%) | ||

| Overall sample | Z-score | 49.24 | 41.41 |

| Maturity Match | 17.22 | 23.16 | |

| GCC Region | Z-score | 48.99 | 61.94 |

| Maturity Match | 25.8 | 33 | |

| Non-GCC MENA Region | Z-score | 35.12 | 20.68 |

| Maturity Match | 40.44 | 44.00 | |

| Non-GCC Asian Countries | Z-score | 55.05 | 57.22 |

| Maturity Match | 27.30 | 25.52 |

is an emerging evidence that the profitability, cost efficiency and stability of Islamic and conventional banks are different before and after the global financial crisis.

It is hoped that this brief chapter will stimulate more research in this area. Future studies should use disaggregated data on specific products to better understand the differences between the products offered by conventional and Islamic banks.

| Profitability Efficiency Stability | |||||||

| ROA | ROE | Cost Income Ratio | Overhead Cost | Z-Score | Maturity Match (%) | ||

| Bahrain | Islamic Banks | 0.041 | 0.100 | 0.684 | 0.733 | 41.07 | 44.95 |

| Conventional Banks | 0.012 | 0.095 | 0.421 | 0.842 | 78.78 | 52.4 | |

| Qatar | Islamic Banks | 0.050 | 0.193 | 0.215 | 0.693 | 67.89 | 63.7 |

| Conventional Banks | 0.023 | 0.184 | 0.523 | 0.819 | 55.15 | 15.1 | |

| Kuwait | Islamic Banks | 0.050 | 0.193 | 0.215 | 0.693 | 59.77 | 15.69 |

| Conventional Banks | 0.007 | 0.087 | 0.285 | 0.472 | 58.79 | 37.01 | |

| UAE | Islamic Banks | 0.018 | 0.095 | 0.347 | 0.744 | 53.70 | 48.1 |

| Conventional Banks | 0.016 | 0.139 | 0.381 | 0.694 | 53.17 | 22.4 | |

| Saudi Arabia | Islamic Banks | 0.022 | 0.128 | 0.538 | 0.893 | 50.65 | 53.3 |

| Conventional Banks | 0.020 | 0.172 | 0.379 | 0.550 | 45.54 | 14.4 | |

| Average GCC | Islamic Banks | 0.036 | 0.121 | 0.511 | 0.748 | 48.99 | 25.81 |

| Conventional Banks | 0.015 | 0.127 | 0.397 | 0.701 | 61.94 | 32.9 |

| Profitability Efficiency Stability | ||||||

| ROA | ROE | Cost Income Ratio | Z-Score | Maturity Match (%) | ||

| Egypt | Islamic Banks | 0.010 | 0.248 | 0.425 | 24.71 | 30.91 |

| Conventional Banks | 0.014 | 0.024 | 0.536 | 22.15 | 43.60 | |

| Jordan | Islamic Banks | 0.011 | 0.181 | 0.475 | 55.04 | 23.06 |

| Conventional Banks | 0.010 | 0.033 | 0.455 | 36.94 | 36.99 | |

| Yemen | Islamic Banks | 0.020 | 0.097 | 0.563 | 21.36 | 49.11 |

| Conventional Banks | 0.010 | 0.017 | 0.473 | 12.43 | 73.42 | |

| Tunisia | Islamic Banks | 0.012 | 0.030 | 0.479 | 112.98 | 5.3 |

| Conventional Banks | 0.009 | 0.024 | 0.494 | 27.16 | 33.32 | |

| Syria | Islamic Banks | 0.018 | 0.012 | na | 5.83 | 93.30 |

| Conventional Banks | 0.013 | 0.016 | na | 0.17 | 61.17 | |

| Lebanon | Islamic Banks | 0.009 | 0.062 | 0.658 | 40.14 | 27.28 |

| Conventional Banks | 0.013 | 0.046 | 0.551 | 0.51 | 37.71 |

| Profitability Efficiency Stability | |||||||

| ROA | ROE | Cost Income Ratio | Overhead Cost | Z-Score | Maturity Match (%) | ||

| Malaysia | Islamic Banks | 0.007 | 0.129 | 0.481 | 0.657 | 67.50 | 39.99 |

| Conventional Banks | 0.015 | 0.151 | 0.446 | 0.782 | 65.29 | 49.74 | |

| Indonesia | Islamic Banks | 0.015 | 0.195 | 0.670 | 0.859 | 62.88 | 21.6 |

| Conventional Banks | 0.029 | 0.198 | 0.863 | 0.910 | 372.69 | 79.3 | |

| Pakistan | Islamic Banks | 0.023 | 0.012 | 0.828 | 0.874 | 66.39 | 28.7 |

| Conventional Banks | 0.000 | 0.160 | 0.341 | 0.476 | 50.16 | 18.68 | |

| Turkey | Islamic Banks | 0.018 | 0.190 | 0.498 | 0.638 | 22.69 | 25.62 |

| Conventional Banks | 0.021 | 0.119 | 0.470 | 0.488 | 6.12 | 27.98 | |

| Bangladesh | Islamic Banks | 0.003 | 0.200 | 0.670 | 0.710 | 25.09 | 19.79 |

| Conventional Banks | 0.014 | 0.171 | 0.813 | 0.820 | 0.19 | 16.30 |