INTRODUCTION

Financial markets need benchmarks for a range of purposes. These purposes are primarily related to reducing information asymmetries concerning the value of traded and non-traded financial assets. Market benchmarks also act as a barometer, helping financial institutions, as well as other economic agents, judge the market conditions.

Islamic finance is becoming increasingly more integrated into global financial system at all levels. Consequently, its potential to bring a population segment that has largely remained outside the scope and reach of financial services into financial inclusion is also increasing. The challenging question, however, pertains to how Islamic finance can sustain its integration into a broader financial system that is mostly interest-based while at the same time remaining pure. Among others, this calls for the development of an Islamic market benchmark, literally an anchor to hold on to, that is responsive to Islamic precepts as well as reflective of the peculiarities of the Islamic economies.

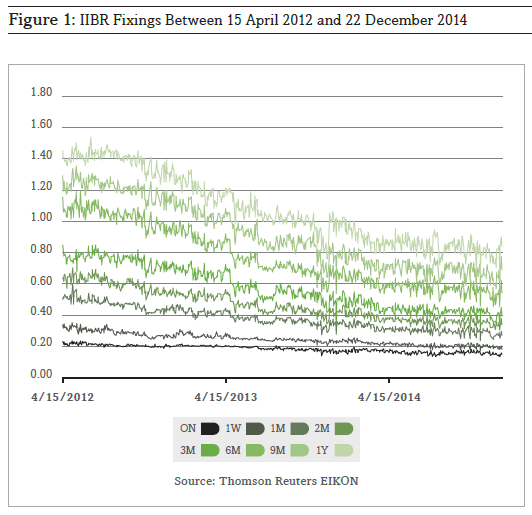

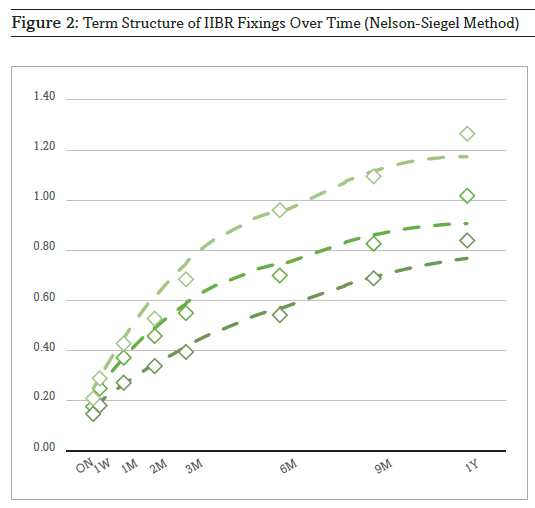

Besides the central desire of ridding Islamic finance of any reference to interest rates, the necessity of an Islamic benchmark is also deeply rooted in numerous Islamic teaching on fair measurement and justice. In the absence of such a benchmark, some Islamic scholars have permitted the use of interest-based benchmarks by Islamic financial institutions as a reference point in measuring their cost of funding, valuing assets and evaluating portfolio performances. Yet, opponents of this so-called illicit practice argue that such a substitution is not valid unless and otherwise the alternative benchmark is derived from the actual performance of real assets that do not contradict the Islamic principles. As an attempt to contribute to the resolution of this ongoing debate, not to its persistence, on November 22, 2011, 17 largest Islamic financial institutions, Thomson Reuters, and multilateral development institutions and standard-setting bodies from the OIC region, including SESRIC, Islamic Development Bank (IDB) and AAOIFI, launched the Islamic Interbank Benchmark Rate (IIBR) which was envisioned to be the first global benchmark of the Islamic finance industry. This attempt also fits into the broader vision of the Islamic Fiqh Academy which, in its Eighth Session held back in 1993, urged for the development of an Islamic benchmark as a substitute for interest rates in the determination of profit margins. Figure 1 depicts the realized IIBR rates on a full spectrum of tenors ranging from overnight to one year. Figure 2, on the other hand, shows the term structure of IIBR fixings through a simple yield curve fitting procedure. It is clear from the figure that there has been a significant downward shift in the term structure of expected Islamic cost of capital, although the rising term structure is preserved (indicated by upward-sloping curves).

In many OIC jurisdictions, Islamic financial institutions continue to be deprived of a financier of the last resort (FOLR) facility and rely on interbank market to avail liquidity. The availability of a broad spectrum of interest-based money market instruments in the interbank market, giving conventional financial institutions utmost flexibility to adjust their short-term cash flows, often means little to Islamic financial institutions. The development of an accurate and reliable Islamic benchmark is therefore an important step towards establishing an effective Islamic interbank market.

THE GOVERNANCE STRUCTURE OF IIBR

The IIBR departs in many ways from its conventional counterparts, particularly the LIBOR. First and foremost, the LIBOR and the likes basically measure the perceived interest rate which would be required for obtaining funding from the interbank market, whereas the IIBR is concerned with the expected return on US$-based Islamic fund placements which, as a convention, is understood by contracting parties as subject to downside risk. Intuitively speaking, rates quoted in the IIBR are meant to attach value to money (which is erwise an intrinsically worthless medium of exchange unless converted to capital and invested in a real economic activity involving real economic risks), whereas LIBOR inherently introduces time value to money, be it converted into real investment or not. Secondly, the IIBR, in the ideal case, will geographically span the economies of OIC countries where Islamic finance is practised and, therefore, be reflective of particular risk characteristics of Islamic economies.

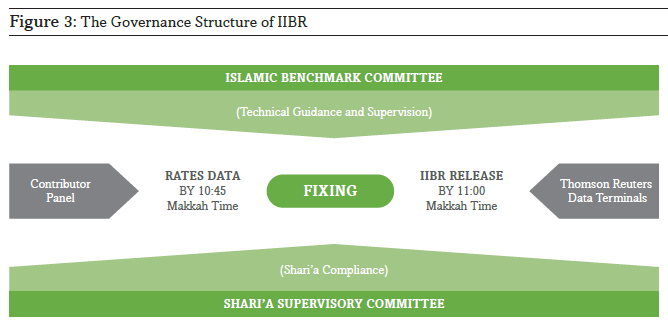

The IIBR utilizes contributed rates from 17 major Islamic financial institutions and fully segregated Islamic windows. As of 2014, total assets of IIBR contributor panel member institutions, excluding the IDB, equalled US$375 billion, constituting a significant share in the global assets of Islamic finance. This adds to the representative power of IIBR. Strong governance structure of the IIBR, on the other hand, aims to proactively safeguard the accuracy, reliability, stability as well as authenticity of the benchmark. The structure basically comprises a committee of industry practitioners and academic experts (Islamic Benchmark Committee), including renowned Islamic finance veterans such as Prof. Abbas Mirakhor, and a committee of Islamic scholars (see Figure 3). The Islamic Benchmark Committee, in this regard, is responsible for the technical oversight as well as providing the necessary guidance pertaining to integrity of the IIBR. The committee of Islamic scholars, on the other hand, undertakes the continuous monitoring of IIBR with respect to its compliance with the Islamic precepts. So far, the IIBR held two annual general meetings with broad-level participation from all member institutions. Strict macro-and micro-prudential checks and balances underlying the IIBR put the benchmark in a stronger position against most of the available benchmarks. For example, a set of strictly observed eligibility criteria is applied to the admission of Islamic windows, and their voting rights are restricted in any case to one- third of total votes on a particular matter. Furthermore, any member absent from two consecutive meetings is immediately considered to have resigned from the membership. This criterion, coupled with a required quorum of at least half of the members, ensures that the challenges surrounding the IIBR as it establishes itself as a reliable benchmark within the Islamic finance industry are confronted on a participatory basis. Besides, unlike the LIBOR, the IIBR utilises ask rates, instead of bid rates, with a view to better reflecting the real liquidity situation in the market and avoid possible cases of adverse selection by contributing panel members in distressed market periods. Finally, rigorous automated and manual checks are performed on the contributed rates on a daily basis against the possibility of misreporting and/or manipulation on the benchmark.

IIBR AND THE COURSE OF DE-COUPLING

Since the last global crisis, the economic center of gravity has shifted considerably towards emerging countries, many of which are members of the OIC. This shift was further strengthened by the rapid divergence between the relative performances of Islamic and conventional financial systems during and, although to a lesser extent, after the crisis. A number of empirical IMF and World Bank working papers have shown us that the Islamic financial institutions remained in a better financial shape and relatively unscathed during the crisis period, and that they in fact contributed to economic and financial stability. Apparently, this was the right time to develop an independent Islamic financial market benchmark which could further increase Islamic financial markets’ visibility and prevent adverse (and, most of the time, irrelevant) connotations which had long been transmitted through conventional benchmarks.

Yet, in the current global market structure which is highly intertwined, an immediate independency and de-coupling of Islamic finance from the conventional financial system and interest-based benchmarks might sound a bit unrealistic. This is particularly so because there is still substantial link between the latter two and the playing field for Islamic financial institutions is still not level, all of which make spill-overs inevitable. Further supporting this point are some demand-side factors. For example, a World Bank survey has recently shown us that, in 48 OIC countries with available data, the proportion of respondents citing religious reasons for not using financial services is only 7%. So, there is also a significant gap between the required and existing awareness levels. This lack of awareness also makes it an uphill task to restrict the flow of funds between Islamic and conventional systems. Ideally, one would expect that Islamic financial institutions do not place any funds in conventional banks, whereas the same restriction would not apply to conventional banks. In this scenario, therefore, we could expect that the Islamic money market equilibrium rate would always be lower than the conventional market equilibrium simply because the money supply in the Islamic money market would always be greater than that in the conventional money market. And, in this scenario, the arbitrage opportunities would always have to be foregone due to the restriction on flow of funds from Islamic to conventional system.

Yet, we live in an idealized world, not necessarily in an ideal one. Economic agents such as firms and individuals, especially those which are indifferent to Islamicity of financial services unless it offers a better rate, will open an indirect line of arbitrage by availing funds from Islamic financial institutions and then parking their excess liquidity with the conventional financial system. And, the result will not only be low-hanging arbitrage opportunities but also lower prospects for any decoupling of Islamic financial system from the conventional one in the short term, even if there is an independent Islamic benchmark.

The literature on Islamic benchmarks, and particularly on the IIBR, is still very nascent and there is a limited number of studies looking at the interdependence relations between Islamic and conventional benchmarks. Some authors concluded that there was no long-term as well as a dynamic relationship between IIBR and LIBOR, except for few tenors. A cursory analysis yields rather contradictory results. The two benchmarks are found to be significantly co-integrated. This means, in more technical terms, they can be expressed as a linear function of each other (plus a stationary random process). This is in line with the mainstream argument that IIBR and LIBOR rates are still interdependent, which is quite understandable given the structural links explained above. With this result in mind, two alternative interpretations follow. First, it might well be that IIBR remains largely a quoted rate (with few actual trades) and the contributed rates are influenced by the rates prevailing in the LIBOR market. Alternatively, it might also well be that IIBR is a truly traded rate and frequent attempts by market players to seize arbitrage opportunities keep IIBR and LIBOR co-integrated. However, the current structure of the IIBR do not allow for a conclusive judgment.

It is interesting to see if there is a causal relationship between the two benchmarks. To test this, the well-known Granger test for causality can be used. For all tenors, the test results suggest significant causality relationships from LIBOR to IIBR, but not in the opposite direction.

Overall, the analysis above has a point. Despite being considered as a milestone in the development of Islamic finance industry, the launch of IIBR did not (and, in fact, should not be expected to) reverse market forces overnight. Almost in all individual jurisdictions and globally, Islamic finance still constitutes only a tiny portion of the overall financial system, which means that the Islamic finance is surrounded by markets that are indigenously tied to conventional benchmarks, such as LIBOR and dominated by conventional financial institutions.

“Despite being considered as a milestone in the development of Islamic finance industry, the launch of IIBR has so far not brought any significant changes to pricing of Islamic financial products.”

Adding to this, Islamic financial institutions also persistently refine the scope of their operations to low-risk, debt-based contracts, rather than adjusting the nature of their financial intermediation according to the higher motives of Islam, such as distributive justice, by adopting more risk-and-return participatory structures.

BROADENING THE USE OF IIBR The real challenge for the IIBR is to establish itself as a reliable point of reference for Islamic financial transactions and let a liquid Islamic interbank market develop around it. This calls for, at the first place, building mass awareness among all stakeholders that there exists an Islamic alternative to conventional benchmark.

It goes without saying that there is a persisting lack of standard interbank structure in Islamic finance. The term lack here refers to:

- The lack of adequate interbank funding lines among the Islamic financial institutions;

- The lack of adequate standardization of Islamic financing modes used for accepting and/or placing funds in the interbank market; and

- The lack of adequate operational efficiency in existing interbank operations. All of these are impediments to broader adoption and use of the IIBR by the Islamic finance industry.

In the current structure of the IIBR, contributing panel members are not required to honor their contributed rates. However, one such measure could be introduced to make the contributed rates softly binding on the contributing institutions, at least for a limited time period. That is, any panel member which is approached for its contributed ask rate by any other panel member can be required to honor its commitment and place funds with the approaching institution, provided that there is sufficient interbank placement limits between the two.

Another quick but possibly effective improvement would be the tracking of transactions executed on IIBR by encouraging the contributing panel members to specifically “tag” such interbank deals as IIBR-related when these deals are executed. This would also facilitate the desired transition of IIBR from “expected” profit rates to those based on “actual” transactions. The success of the implementation phase, however, hinges on having adequate number of transactions between the contributing panel members each trading day. Surprisingly, there are reportedly few actual transactions between rate-contributing financial institutions even in the most widely used benchmarks, such as LIBOR, and even including the most popular tenors.

The IIBR contributor panel members in particular and the Islamic financial industry in general can be encouraged to adopt a reasonable target ratio for their level of use of IIBR relative to the total size (or number) of their transactions. Later on, this ratio could be increased gradually. In fact, a recent survey prepared jointly by SESRIC and Thomson Reuters and circulated to IIBR panel members, aims to develop an initial understanding about the current market use of IIBR among contributor panel members and beyond, and can be a stepping stone towards a more structured adoption strategy.

Referring to the current over-representation of the GCC region in the IIBR contributor panel, some industry experts argue that the Islamic benchmark may not be able to adequately represent the market dynamics in other Islamic financial markets such as those in Asia and Africa. This argument seems to have a point, even if one considers the predominant role of the GCC countries in the global Islamic finance industry. An expansion of the geographical base of IIBR, on the other hand, would require the inclusion of some major Islamic currencies in the fixing (also given the differences between the Islamic countries with regard to their policies for the market amount of US dollars) as well as the achievement of greater harmonization of interbank structures and products across different OIC regions. The latter could be done possibly in collaboration with institutions such as the IILM which are tasked with developing cross-border Islamic liquidity products.

Finally, it is worth reminding ourselves that Islamic finance activities are more comprehensive than those of conventional finance. Islamic financial institutions need to assume a broad spectrum of roles including being a trader, custodian, partner, entrepreneur, agent (wakeel) and guarantor. Therefore, in the medium- to long-term, the IIBR cannot remain solely based on financial contracts related to intermediary functions.

RIGGING OF LIBOR AND LESSONS FOR IIBR

One argument put forth to justify the use of LIBOR among Islamic finance practitioners has been its relative stability and transparency. But this was proven to be no more valid with the prevailing disconnect between LIBOR and the rate of return in the real economy particularly during the global financial crisis of 2008 and, more recently, with the LIBOR scandal which sparked an intense debate on the benchmark’s reliability. Subsequent research has revealed a substantial and persistent downward bias in LIBOR fixings relative to actual borrowing rates in the market.

As Douglas Keenan, an independent mathematical scientist and former Morgan Stanley securities trader based in London, strikingly put it in his op-ed to Financial Times on 27 July 2012, “the misreporting of LIBOR rates may have been common practice since at least 1991” (Keenan, 2012). He further added that London banks since then had misreported the LIBOR rates in a way that would generally bring them profits. In fact, there was another distinct motivation for London banks to misreport LIBOR rates, which arose during the last global financial crisis: to mask liquidity problems.

In a recent paper entitled “Reforming LIBOR and Other Financial-Market Benchmarks,” Stanford and Harvard University Professors Darrell Duffie and Jeremy Stein suggest two overarching principles that any attempt to reform existing benchmarks or build a new one should take care of (2014). First, benchmarks should be based, to the greatest practical extent, not on judgments of contributing institutions, but on actual transactions. Second, greater use of a diverse set of alternative benchmarks should be encouraged to avoid possible agglomeration of trade around a single benchmark, which results from the market participants’ natural tendency to be in close orbit of high-liquidity markets and instruments, such as those linked to LIBOR. According to Professors Duffie and Stein, such massive agglomerations of trade and liquidity, coupled with potential weaknesses in the fixing methodology, can always be a source of incentive to manipulate the benchmark.

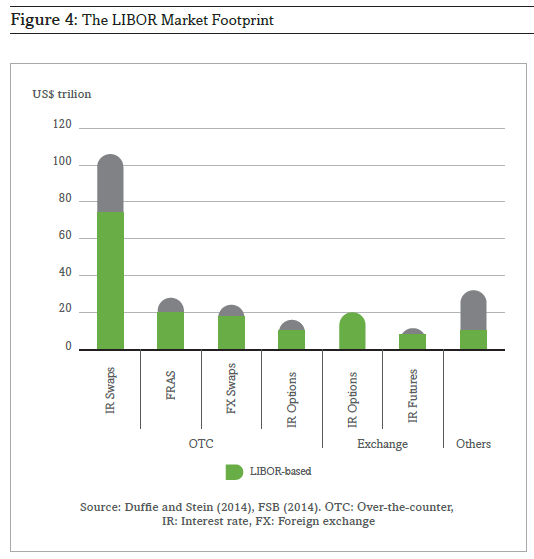

One particular challenge for the IIBR in its endeavour to turn the tide for Islamic finance industry therefore stems from the excessive and sticky agglomeration of trade around the LIBOR, i.e., the difficulty for the market to switch to a new benchmark choice on its own. Figure 4 further illustrates this point by showing how the majority of outstanding financial contracts globally are indexed to, and therefore will potentially remain stuck on the LIBOR.

A critical takeaway from the recent experience of LIBOR is that the first line of defence should be a benchmark definition and a fixing methodology that are simply difficult to distort, and this is particularly true for judgement- based contracts, such as the IIBR.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

From a contemporary historical perspective, the IIBR can be seen as an important link in the chain of Islamic finance development milestones which started with the launch of IDB in 1975, followed, inter alia, by the establishment of AAOIFI (1991), issuance of first international Sukuk (2001), and the establishment of Islamic Financial Services Board (2002).

The IIBR is probably the first step, not necessarily the last, towards the detachment of Islamic finance industry from conventional system and interest-based benchmarks. As its basin of attraction grows, the Islamic benchmark can increasingly become a source of decoupling, as well as increased visibility for the Islamic finance industry.

Going forward, Turkey’s G20 presidency for 2015 will certainly blow a breath of fresh air into global development of Islamic finance as the government of Turkey, through its key priorities document, is highly committed to promoting unconventional financing mechanisms, particularly including those based on equity and/or asset partnerships. At this juncture, it is important that the Islamic finance industry takes the necessary steps to gain further independence and authenticity through greater adoption as well as collective enhancement of industry initiatives such as the IIBR.