Introduction

With assets recently reaching the US$ 1 trillion bar, the Islamic finance industry’s growth and reach have become impossible to ignore. With assets quadrupling over the past three years, it is safe to say that conventional finance has not shared the same momentum, on the contrary. Many experts today ask the question whether the global financial crisis we know today could have been averted by a financial system based on Shari’a principles. Such a scenario is an interesting one to consider: had the Islamic principles of full transparency and disclosure, fairness towards the customer and profit sharing amongst investors been applied, there is a chance the financial crisis would not have had the same magnitude. Here, we explore the strengths and the weaknesses of the Islamic banking system as well as the opportunities and challenges brought on by its globalisation.

A historical overview

Before delving into this chapter, we would like to supply the reader with a brief historical overview of the Islamic banking industry. Although Shari’a-compliant credit un- ions have been established in Pakistan and Egypt since the 1950s, the general consensus is that Islamic banking as we know it can only be traced back to the mid-1970s. The modern financial services sector started to flourish in the Gulf during this period fuelled by increasing oil wealth. With real disposable income rising steadily, a growing share of the finance sector of the region took the form of Shari’a-compliant retail banking. It therefore allowed increasingly demanding and sophisticated customers to deposit their savings in a secure and formal banking structure without having to compromise their religious beliefs. More specifically, the profit made from their investments would neither earn nor be used to generate riba (inter- est), which is strictly prohibited by the Holy Quran.

The financial institution spearheading Islamic retail banking was Dubai Islamic Bank (DIB), founded in 1975. Today, the Emirati bank describes itself as “the world’s first fully-fledged Islamic bank” and comprises activities such as commercial and investment banking. Retail financial services, however, continue to constitute the backbone of DIB’s overall franchise, contributing about a third of the bank’s revenues. Its 57 branches in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) now serve some 750,000 retail customers, while its modest but fast-growing international exposure is represented through its retail banking operations in Pakistan, Jordan and Turkey.

In 1977 the Kuwait Finance House (KFH) was founded and was the first bank in the country to operate exclusively in accordance with Shari’a law. By the end of 2006, it accounted for about a quarter of all deposits in the Kuwaiti market¹ and was also continuing to expand its overseas operations. Today, KFH has more branches in Turkey than in Kuwait and is also very active in Malaysia. Recently, KFH expanded its operations to include representative offices in Singapore and Melbourne, demonstrating the increasingly global reach of Islamic retail banking.

Among other Gulf countries, Bahrain and Qatar opened their first dedicated Islamic banks in 1979 and 1982 respectively. Elsewhere, the spread of Shari’a-compliant financial services were underpinned by the passage of legislation which made Islamic banking compulsory in countries such as Pakistan (1979), Iran (1983) and Su- dan (1984).

In South-East Asia, the Malaysian Islamic banking industry has undergone the most spectacular expansion over a short period of time. The growth of the industry was encouraged by the enactment of the Islamic bank-

ing Act (IBA) in 1983 and the establishment of Bank Islam Malaysia the following year. Today, Malaysia has 17 dedicated Islamic banks, nine of which are subsidiaries of domestic banking groups, accounting for 17.4% of total banking assets in the country.

The Islamic banking boom

The beginning of the 21st century has seen a radical change: the number of Islamic banks significantly in- creased and their geographical spread has grown exponentially to cover all continents. According to statistics published recently by Maybank, one of Malaysia’s top-ranking banks, there are now 614 registered Shari’a-compliant institutions in 47 countries, 420 of which are dedicated Islamic financial services companies. The remaining 194 are conventional institutions with Shari’a windows. The Islamic banking industry’s growth and promising future is further validated by the growing number of major conventional financial institutions embracing Islamic banking. HSBC, BNP Paribas and RBS to name but a few, have all opened Islamic units to capture a share in this burgeoning market. Joint ventures between global players and local experts also increased over the past few years, demonstrating the strong potential of Islamic banking worldwide.

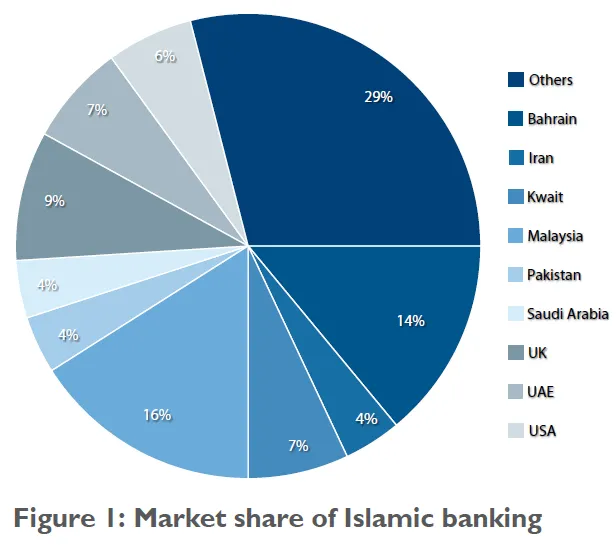

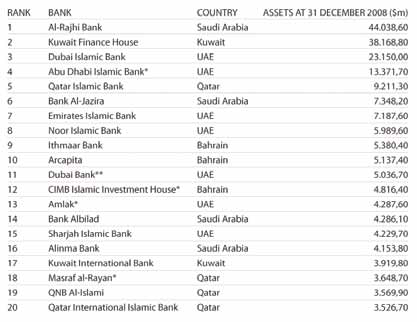

According to a research by MEED published on 9 July 2009, the top 20 banks (by asset size) in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries (GCC) have seen their combined assets grow by 24 per cent in 2008 to US$ 200 billion from US$ 151 billion in 2007. Al-Rajhi Bank, the Saudi bank, ranks first in the region, recording a year-on-year asset growth of 24% to US$ 44.03 billion in 2008 (21% of market share within the top 20 banks). The report also notes that the outlook for GCC banks in 2009 is healthy, which is primarily due to their governments’ favourable monetary policy. As the cash injections boost the flow of credit through the banking system, Gulf banks are expected to record another year of growth. The Islamic financial services volumes are growing over 20% per annum and have just reached the US$ 1 trillion mark; a year ahead of what had been forecast by analysts. However, Islamic assets are estimated to ac- count for only 1% of total worldwide banking assets, just the tip of a very big iceberg as the Muslim community accounts for 20% of the world’s population. Some estimates suggest that in oil-producing countries alone, Islamic finance will account for 50% of all banking assets within the next 10 years.

A chink in the Islamic banking armour

However, in order to give the full picture, it would not be right to say that the Islamic banking sector hasn’t been affected by the recent financial turmoil. Currently, we see banks being downgraded as well as exposed to defaults and restructurings in the sukuk market. Another issue is the concentrated exposure to a limited number of sectors such as real estate. According to Ernst & Young, Islamic banks have been heavily exposed to the real estate market, which saw prices starting to plummet at the end of last year.

They channelled the wealth accumulated during the six-year oil boom that ended in mid-2008 into regional real estate through private equity and asset management and relied heavily on selling investments and placements in that sector. The global liquidity constraints now force Islamic banks in the GCC region to adopt new business models and take on more customers to weather the economic downturn, including moving into corporate banking, trade finance and retail banking. Omer Khan, Islamic Finance expert at PricewaterhouseCoopers in Ireland, says that “we may start to see some consolidation in Islamic banking as wholesale banks seek to expand into the retail space as a way of tapping into the existing deposit base.”

Three-way diversification brings opportunities

Statistics on the growth of Islamic banking, however, tell only a fraction of the industry’s story. More significant than its top-line expansion in terms of total assets has been its diversification at three significant levels: market participants, geographical reach and products.

Over the past few years, we have seen the emergence of three new categories of market participants: new dedicated local banks, new Islamic windows within conventionally-oriented players and finally, international banks, which established dedicated Shari’a-compliant units, both in Muslim-majority countries and in the markets in which they are headquartered. HSBC (through its Amanah unit) and Standard Chartered (via its Saadiq brand) are perhaps the best-known examples of multinational banks that have built up successful global retail Islamic banking divisions.

The direct result of the diversification of market players was the growing geographical reach of the industry. It has led to the emergence of a number of new financial centres for Islamic financial services, complementing those that have historically been of pivotal importance for Shari’a-compliant banking, most notably Dubai, Bahrain and Kuala Lumpur. Hong Kong and Singapore are also becoming increasingly prominent locations for Islamic banking.

Other countries with sizeable Muslim minorities have also seen the emergence of flourishing and increasingly diversified local Islamic banking sectors over the last two decades. The most striking example in Eu- rope is the UK, which is home to an estimated two million Muslims and to about 130,000 Muslim-owned SMEs5. United Bank of Kuwait (UBK) started offering Islamic mortgages in the UK as early as 1996. More recently, high-street banks such as HSBC (starting in 2003) and Lloyds TSB (in 2005) have been marketing staple retail banking products such as Shari’a-compli- ant home loans and current accounts. Today, there are five exclusively Islamic banks operating in Britain.

France is also progressing in the field of Islamic banking: the French financial authorities are currently in the process of granting the first-ever Islamic banking license on its territory.

Retail banking products

Dovetailing the geographical expansion, the growth of Islamic finance can also be explained by the emergence of an increasingly broad range of retail Shari’a-compliant products and services, which in turn has helped the industry challenge conventional banking in terms of innovation. In the formative days of the modern Islamic banking industry, products offered to retail customers were restricted chiefly to rudimentary deposit accounts and Murabaha-based facilities. In a murabaha agreement, the bank acquires goods on behalf of the customer who then purchase the goods from the bank on a deferred basis at a small premium which is the bank’s agreed profit margin.

The same mechanism, as well as the diminishing musharaka (co-ownership plus rental) concept, has also been the cornerstone of the growth of the Shari’a-compliant mortgage market in Islamic communities throughout the world. By acquiring properties and leasing them back to consumers over an agreed term, Islamic banks have played a pivotal role in bringing home ownership within the reach of millions of Muslims uneasy about paying riba on conventional home loans. In the UK, for example, the local Alburaq division of Arab International Bank (ABC) had approved more than GBP £100 million of Islamic residential mortgage loans within three years of opening for business in 20047.

Other Shari’a-compliant retail banking products that have grown in popularity in recent years have included auto and consumer loans, as well as charge and credit cards based on the principle of bay’ bithaman ajil (deferred payment sale).

Investments and savings products

A comprehensive suite of savings products targeted at Muslim investors and distributed through conventional and Islamic banks have also evolved over the last three decades. In Saudi Arabia, National Commercial Bank (NCB) begun promoting mutual funds in the 1970s, launching the first dedicated Shari’a-compliant vehicle – the Al Ahli International Trade Fund – in 1987 and add- ing a range of equity-based funds in the 1990s. By 2008, Saudi Arabia had 127 Shari’a-compliant mutual funds, paving the way for a further 45 in Kuwait, 29 in Bahrain and 2 in Qatar.

This growth is mainly due to the increased adaptability and sophistication of Shari’a-compliant funds. In the early days of the industry, it was assumed (principally by international fund management groups) that Islamic equity portfolios could be constructed through a simple process of stock-screening. That process, it was erroneously assumed, would simply remove companies involved in activities that violate Islamic law, such as those producing alcoholic products or promoting gambling.

Much less straightforward, however, was how to measure the religious permissibility of companies generating income through cash on their balance sheets deposited at conventional banks and earning interest in the process. That complication has been addressed by pragmatic Shari’a scholars giving their blessing to mechanisms such as “tanqiyyah” (dividend purification).

An important trend in the development of Shari’a-compliant investment funds is the recent emergence of products such as Islamic bonds (sukuk), which have broadened the investment possibilities for retail investors. According to statistics published by the Bahrain- based Unicorn Investment Bank, issuance of sukuk rose from just US$ 1.56 billion in 2001 to a peak of US$

33.76 billion in 2007 before falling back to US$ 14.9 billion in 20089. A number of banks have responded to this growth, and to Muslim investors’ concerns about the volatility of equity markets, by setting up Shari’a-compliant sukuk funds.

The market expansion for Islamic asset management is coinciding with the breathtaking growth of Shari’a-com- pliant insurance (takaful). According to figures published by Ernst & Young10, gross takaful contributions rose at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 30% be- tween 2005 and 2007, with projections of the global market for Shari’a-compliant insurance reaching US$ 7.7 billion by the end of 2012.

The growth in the takaful market is also offering considerable opportunities for retail banks looking to establish joint ventures with specialist Shari’a-compliant insurers. To date, the bancatakaful model, which aims to combine insurance companies’ product expertise and banks’ distribution strengths, has been most successfully developed in South-East Asia. Successful bancatakaful ventures in Malaysia have been established by BSN and Pru- dential, CIMB and Aviva, Maybank and Fortis and Public Bank and ING. In Indonesia, Bank Mandiri and France’s Axa have pooled their resources to create a pioneer in the local bancatakaful arena.

The flipside of the coin: Co-existence and competition with conventional banks

Increased competition from local as well as international players is increasing the pressure on some of the dedicated Islamic entities to reappraise business models that have served them well in the retail banking market space for decades. This is true even in economies that have traditionally been largely protected from the competitive threat of international banks, such as Saudi Arabia.

Take Al Rajhi Bank for example, which has assets of US$ 44 billion, some 430 branches (over 100 of which are outlets dedicated to female customers), 2000 ATMs, more than 8000 employees and a domestic market share of 13% of banking assets11. That makes Al Rajhi the largest Islamic bank in the world, while the strength and reach of its retail franchise has also made it one of the most profitable banks in the Middle East.

Moody’s comments that one of the constraints on Al Rajhi’s rating is “the increasingly competitive nature of the Islamic banking industry.” The bank is, however, respond- ing very constructively to the growing intensity of competition in its core Islamic finance franchise, by exploring a number of alternative growth opportunities. Just as Kuwait Finance House before it, Al Rajhi is expanding into overseas markets, having built up an increasingly extensive network in Malaysia. It is also channelling additional resources into its corporate and investment banking divisions as well as into its mortgage lending operations.

For providers of Islamic retail financial services, the development of a more comprehensive, sophisticated suite of services and a broader global presence are bringing fresh challenges. One of these is the standardization of products in varying cultural and linguistic contexts and consequently, as many Shari’a laws interpretations. Establishing local partnerships and joint ventures, or while-labelling products for distribution by local specialists, maybe a solution for providers of Islamic financial services looking to roll out a more diversified product offering.

According to a report from Oliver Wyman issued in 200912, although they have not been fully explored, the following potential business models all have strong prospects going forward:

- Third-party distribution specialist: focusing on consumer finance and distributing through retailers (e.g. white goods, car dealers). It is well suited to Islamic finance, which is asset-based and allows lower distribution costs from capturing the customer at the point of sale.

- Mortgage specialists: demographics are particularly strong in key Islamic finance markets and housing de- mand is buoyant. Most Islamic banks lack a good mortgage offering, therefore leveraging these networks to push a well-designed product will allow rapid growth and international expansion.

- Deposit specialist: asset gathering is still underdeveloped and most Islamic banks rely on a passive depositor base. Actively-managed deposit accounts with attractive profit-sharing will benefit from increasing customer sophistication. Collecting deposits can be accomplished through e-channels or a post-bank partnership to minimise costs.

Another apparent challenge faced by the Islamic financial services industry is the pressure that its rapid growth is putting on human resources and expertise that are in short supply. Authorities in the leading financial cen- tres have responded constructively to this constraint by backing key educational and training institutions. The Malaysian Central Bank (Bank Negara), for example, has supported the establishment of organisations such as the Islamic banking & Finance Institute of Malaysia (IBFIM), the International Centre for Education in Islamic Finance (INCEIF) and the International Shari’a Research Academy (ISRA). Efforts that have been recognised from afar: in July 2009, The Lord Mayor of London Alderman, Ian Luder, praised Malaysia’s efforts in that domain and encouraged professional exchanges between the two countries’ Islamic finance staff, experts and student. During his speech at the Malaysia-UK Islamic Finance Forum in Kuala Lumpur, he also highlighted the necessity of joint education programmes.

Islamic and conventional products: Comparisons and convergence?

Although many of the banks’ Muslim customers will inevitably migrate towards Shari’a-compliant financial services as Islamic banking grows, it is generally recognised that Shari’a-compliant retail banking has an important role to play in complementing conventional banking. In many areas of the industry, that will lead to increased convergence of the two systems.

One example of convergence between Islamic and conventional retail financial products which is expected to gather momentum over the next few years is the increased overlap of the investor base for Shari’a-com- pliant funds. McKinsey has estimated that new inflows into these funds will grow at an annual rate of about 25% between now and 2011, which is 50% higher than the inflows in the same period into conventional funds. Much of those inflows will, of course, be accounted for by Muslim savers eager to align their portfolios with Islamic law.

But much will also be generated from non-Islamic savers increasing demand for socially-responsible investment opportunities. More and more, industry specialists see parallels between socially responsible investing (SRI) and Islamic investing such as the decentralized decision-making (via a Shari’a board for Islamic investing and an Ethical board for SRI) to retain the ethical aspect of the investment and the industry sectors they invest in which exclude tobacco, alcohol, armament or gambling, as they are deemed unethical. The prohibition of usury and its replacement with a system whereby profits and risk are shared more equally is a principle that resembles that of SRI. In recent years, SRI has developed with a strong focus on sustainable development in its economic and social principles: creation of wealth for society and improvement in the quality of life.

Islamic mutual funds may also be popular with investors looking to protect their portfolios from risky activities such as sub-prime lending and the irresponsible use of derivatives. Indeed, these had a very negative impact on conventional indices in the recent equity bear market, but were much less damaging to the performance of Islamic stock indices. As S&P commented in an update published in April 2009, “while global markets continued their retreat in the early months of 2009, Islamic investors felt the repercussions much less due to the absence [from Shari’a indices] of the badly hit financial industry and companies operating with high leverage.” The same report added that “despite ongoing market volatility, Shari’a investing continues to attract market share from conventional Western investors as well as the Islamic investment community.”

The future and the challenges ahead

In spite of its impressive growth over the last three decades, the potential for continued expansion of Islamic retail banking remains considerable, both in terms of continued geographical diversification and product innovation. This is underpinned by the strong demographics of major Muslim countries. By 2020, the population of the top 10 Muslim countries will grow by nearly 200 million, with over half of the population still under the age of 25. As this new generation enters adulthood, the retail customer base is set to double in the same period.

Recent initiatives in countries such as Nigeria and China attest to the longer-term potential of global expansion in the market for Shari’a-compliant retail financial services. The most intense focus for many international banks assessing the potential for expansion of Islamic retail banking, however, will be on continental Europe. In particular, it will be on the European Union’s two leading economies, France and Germany, both of which have large Muslim populations who have traditionally been unable to save or borrow in compliance with their religious beliefs.

France has by far the largest Muslim population (6.4 million) in Europe. According to a recent S&P report, “given the size of this target market, we believe that a latent demand for Islamic finance exists in France but has never been tapped as no Islamic finance offer is available.” That is now set to change, with the French government committed to supporting the growth of a domestic Shari’a-compliant industry which will create a wealth of opportunities for leading French banks.

Germany is also expected to develop into an important market for banks offering Islamic financial services. Ger- many has a Muslim population of about 3.2 million, with combined assets of €20 billion and an estimated annual savings rate of €2 billion.

Sweden, for example, is home to one of the fastest-growing Muslim populations in Europe, and in theory, is a market of considerable potential for Islamic banking. In practice, however, local banking laws are likely to hamper the evolution of a Swedish market for Shari’a-compliant mortgage lending, which is based on banks acquiring properties and selling them on to consumers. This arrangement is impractical, as banks in Sweden are barred from owning real estate for purposes other than their own use and as purchases and sales of residential property are subject to stamp duty, which would need to be paid twice. Sweden has yet to follow the UK by amending its legislation on stamp duty to exempt Muslim homebuyers from double taxation.

While Islamic retail banking is expected to continue expanding its geographic footprint, the range of products the industry is able to offer its customer base is also projected to grow, as banks become more innovative and Muslim depositors and savers become increasingly demanding and sophisticated.

According to the Oliver Wyman report, execution excellence is the key to success and some distinct initiatives can contribute to it: development of a differentiated but non-discriminating offering, improvement of product development to address Islamic product structuring constraints, enhancement of processes and product delivery to improve service and sales efficiency and finally, adaptation of marketing and customer proposition to Shari’a principles.

In that respect, many bankers believe that products related to Shari’a-compliant derivatives or Islamic hedge funds may represent the next step for the industry. Products of this kind are already being developed by a number of conventional and dedicated Islamic banking windows and the efficiency with which they are delivered to retail customers will depend on the capacity of banks to act as distribution channels.

Sohail Jaffer is a partner and the Head of International Business Development for “white label” bancassurance and investment services within FWU Group, an independent financial services group headquartered in Munich whose main activities include Bancatakaful, asset management and individual pension plans. Its international network includes the Middle East, Pakistan, Asia and other Emerging Markets.

The information provided in this article does not constitute investment advice from FWU Group and shall not in this regard imply legal obligations for the FWU Group or anybody else towards the readers. FWU Group cannot be held responsible or liable for the content of the external references and websites used in good faith to illustrate points made by the author of the article, nor does FWU Group guarantee the accuracy or completeness of those external sources. This article may not be reproduced nor circulated prior written consent of FWU Group.