The Islamic banking and finance (IBF) industry has evolved from over the last five decades as an important Islamic financial system. With worldwide acceptance Islamic financial services are now being offered by more than 1,000 institutions in 75 countries. The personalities and institutions that initiated IBF benefitted from their first-mover advantage and have developed themselves into credible competitors to the existing conventional banks and financial institutions. Similarly, some of the products that were introduced in the early days underwent a process of transformation, evolvement and enhancement and have now become irreplaceable as well as competent when compared to conventional products. The development of IBF has given rise to some of the most important products. This chapter discusses some of the important products that have contributed to the growth of IBF and are defining the way forward for the industry.

Sukuk

The emergence of sukuk has been one of the most important developments in IBF, especially in the aftermath of the financial crisis. Sukuk is also regarded as one of the fastest-growing sectors in Islamic finance and is considered by many as the most innovative product of Islamic finance. The sukuk issuances in the last 10 years have become attractive to not only corporates but government bodies and financial institutions as well. Sukuk can link issuers with a wide pool of investors from different geographies and across various segments and offer diversifications to the traditional asset classes. However, within the Islamic financial system, sukuk market is a new development. The first corporate sukuk was issued by Shell MDS (Malaysia) in 1990. After that, there were no active issuances by other players or markets until 2001 when Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura (MUIS) and the Government of Bahrain, issued sukuk. The first global corporate sukuk was issued by Guthrie Malaysia. This also marked the start of an active sukuk market.

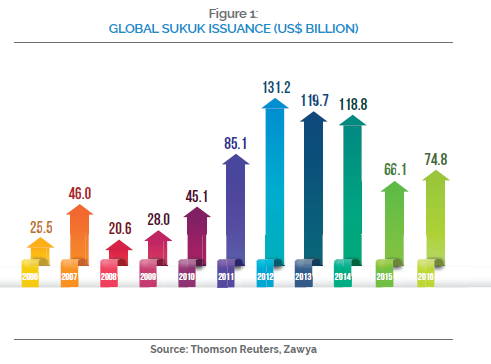

The sukuk industry took off in the year 2010 after the global financial crisis. Prior to the financial crisis the sukuk market peaked in 2007 to US$47 billion issuance in that year alone. However, after the famous pronouncement by Justice Mufti Taqi Usmani that most of the existing sukuk are Shari’a non-compliant, the market took a hit and sukuk issuances dropped by 55%. The total sukuk outstanding in 2010 were only worth US$180.03 billion, issued globally since 1996. At its peak, global sukuk issuance came close to US$131 billion in 2012, but posted three consecutive years of decline to reach US$66.1 billion in 2015 (Figure 1).

The subdued issuance volumes in 2015 were the result of external factors affecting global financial markets but mostly driven by the Bank Negara Malaysia’s resolution to cease issuance of its short-term sukuk and opted instead to switch to other instruments for liquidity management for Islamic financial institutions. In 2016, global sukuk market witnessed a rebound after reaching US$74.8 billion in 2016, posting a 13.2% growth from previous year. Global sukuk outstanding recorded an increase of 8.7% in 2016 to register US$349.1 billion from US$321.2 billion as at end of 2015.

Malaysia is currently the largest sukuk issuer after commanding a market share of 46.4% of total issuances and is expected to continue playing a significant role together with Indonesia and the United Arab Emirates, which accounted for 9.9% and 9.0% share of global sukuk issuance in 2016. Total issuances of GCC countries stood at US$19.6 billion, compared to US$18 billion in 2015, driven by higher issuances from sovereigns. However, in 2017 the GCC may likely take a larger share as more issuance are expected to come out of the GCC countries to finance their large budget deficits and infrastructure projects.

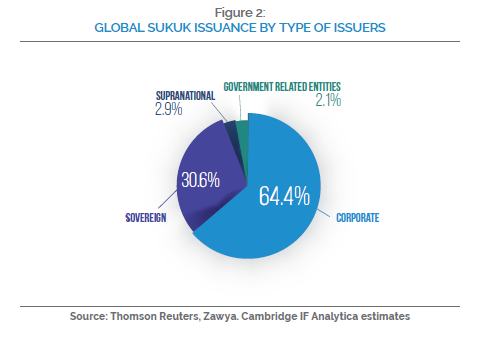

While it is Malaysia that is driving the sukuk growth in the IBF industry, it is the corporate sukuk that is driving the type of issuers. By end of 2016, corporate sukuk issuance was US$48.17 billion, followed by sovereign sukuk issuance of US$22.89 billion (Figure 2). Within the corporate sukuk issuances, financial services sector leads by 78% of total issuances, sukuk followed by power and utilities, oil and gas, and transportation. While 2016 saw a number of high-value corporate sukuk, sovereign sukuk issuances have really taken centre stage. Pakistan returned to the market after an absence of almost two years, Qatar issued sukuk with a total value of over US$400 million, and Bahrain completed a dual-tranche transaction that was heavily oversubscribed.

West Africa has seen a particular uptick in sukuk issuances in recent years with a host of new issuances in 2016. The governments of Senegal raised CFA300 billion in June 2016. The Republic of Côte d’Ivoire issued its second sukuk in 2016 for a value of CFA150 billion (US$244 million), following its debut issuance of the same value in 2015. The Republic of Togo issued its debut sukuk of CFA150 billion later in the year. Other African countries such as Kenya and South Africa are planning issuances in 2017. However, the same enthusiasm was not prevalent in the GCC countries, with many preferring to issue conventional debt over sukuk due to its perceived ability to attract global investors and the low-interest environment as quantitative easing drove yields to zero or even negative rates in some markets. Qatar and Saudi Arabia, for example, opted to fund their budget deficits with conventional bonds.

However, two major events in 2016 that will help boost the sukuk market (infrastructure sukuk in particular) in 2017 are the launched of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 and the lifting of international sanctions on Iran. Unveiled in April, the plan aims to shift the Kingdom’s economy away from its dependence on oil revenue, increase non-oil government revenue and increase private sector’s contribution to GDP. It is anticipated that Vision 2030 could potentially contribute to the growth in sukuk market as the Kingdom turns to sukuk issuance to fund its large-scale infrastructure projects.

Iran’s returned to the global market is expected to drive sukuk issuance as the country entire financial sector is Shari’a-compliant with the passing of the Law for Usury Free Banking Operations in 1983. Due to the sheer size of the country’s investment needs, the government will be looking at issuing sukuk as it shifts its funding needs to the capital market. Nevertheless, Iran needs to review its current legislation, which forbids sukuk trading in foreign currencies, if it wants to tap the international sukuk market.

There is growing potential for green sukuk in the GCC. Green sukuk is set to open another avenue of funding in the GCC and could mobilise essential finance needed to fund the rising number of clean energy initiatives throughout the GCC as they begin to set targets for sustainability and clean energy. The market can expect to see more ‘green’ sukuk issuance to originate from the GCC countries in the coming years. For example, Abu Dhabi announced a target of generating 7% of its energy capacity from renewable sources by 2020. Similarly, the Dubai government has also stated its goal of financing clean energy and efficiency goals through sukuk. In 2015, Dubai launched the Dubai Clean Energy Strategy 2050, which aims to make Dubai a global center of clean energy and green economy. In Saudi Arabia, the ACWA Power company announced their intentions to finance renewable energy projects through sukuk.

Islamic Funds

The Islamic finance value chain begins with Islamic banking and continues through to the takaful business and into capital markets. At the tail end of this value chain, Islamic asset management exists to service the investment needs of these other components. Islamic asset management, dubbed as the “new frontier” for the global Islamic finance industry, has undergone a fundamental change in recent years. Increased regulations, geopolitical uncertainty and market volatility are some of the profound challenges reshaping the industry.

Islamic funds are still in their infancy, compared to conventional and socially responsible investment funds, both in terms of assets under management (AUM) and growth. Islamic funds represent a mere 5% of the total global Islamic finance assets. About 71% of Islamic funds have AuM less than US$25 million, which primarily means that these funds have not reach critical mass that is necessary for efficiency and sustainability. However, there is substantial growth opportunities in Islamic funds as the supply-demand gap for Islamic AuM is estimated at US$87 billion. This supply-demand gap is expected to widen as the global Islamic asset management industry is forecasted to grow to US$77 billion by 2019.

In the recent ICD-Thomson Reuters Islamic Finance Development Report 2016, global Islamic funds are projected to reach US$77 billion in 2017 and US$105 billion by 2021. Overall, 2016 was another slow year for Islamic asset management after the global Islamic funds fell 1.6% in 2015, reflecting the sluggish global market environment. The persistent low oil prices since 2014 further dampened Islamic funds growth, predominantly in oil-exporting countries. Several global events weighed in on the overall performance of Islamic funds in 2016 including global macroeconomic conditions and geopolitical events in the GCC and Southeast Asian countries, which are the two main regions where Islamic funds are heavily concentrated. In terms of geographical area, the GCC has the largest proportion of AuM Islamic funds outstanding at 37%, followed by the Southeast Asia region at 30%. The top three countries in terms of the percentage of Islamic funds outstanding are Saudi Arabia, Malaysia and Iran; together making up 81% of total global Islamic funds’ AuM. Meanwhile, the US and Luxembourg are major centers where Islamic funds are domiciled, representing 4% and 3%, respectively, of the Islamic fund market outside the Muslim world.

Islamic Equities

Islamic equity is fast becoming a popular asset class. Equity Islamic funds, which made up 51% of total Islamic funds outstanding, had a rough year in 2016 primarily due to the heavy exposure to the GCC equity markets. The Islamic equity market covers Shari’a-compliant shares of companies that do not engage in activities that are prohibited in Islam. Hence, Islamic equities are required to go through a Shari’a screening process, which ensures that the business, mode and capital structure of the businesses are in line with Shari’a. In addition, these companies should also comply with Shari’a norms pertaining to their financials, which include tolerance level of interest-bearing debt, interest-based income and earnings and receivables, cash and bank balances.

Companies that do not comply with Shari’a norms related to their businesses and financials are declared prohibited for Shari’a-compliant investors. In principle, the Islamic equity market is characterized by the absence of interest-based transactions, doubtful transactions and the holding of shares in companies that deal in non-Shari’a-compliant activities or items. Hence, from a Shari’a-compliant investment point of view, the key element to equity funds is the screening criteria used to determine the status of the companies in which investment is to be made. This requirement for screening companies prior to investment is derived from the Shari’a principle that Muslims should not partake in any activity that does not comply with the teachings of Islam. At present, there are numerous screening methodologies being developed and approved by renowned Islamic scholars that are being used by financial institutions around the world.

BOX ARTICLE 1

Islamic Crowdfunding

Crowdfunding is a type of crowdsourcing, which can be defined as a type of participative online activity in which an individual, institution, non-profit organization, or company proposes to a group of the voluntary undertaking of a task which always entails mutual benefit. The crowd participates bringing work, money, knowledge and/or experience. Crowd funding is the application of this concept to the collection of funds through small to medium-size contributions from a crowd in order to finance a particular project or venture, offering small businesses and entrepreneurs a chance at success.

Islamic crowdfunding is an ethical form of financing that focuses on values and ethics that are universally accepted. This resonates well with other investment screens such as Environmental, Sustainable and Governance (ESG) and socially responsible investing (SRI). The positive difference is that Islamic finance adds another filter based on Islamic Law, which prohibits the use of interest and excessive risk-taking or uncertainty, among other things. Hence, the development of Islamic crowdfunding platforms and products can potentially promote more risk-sharing activities. Most crowdfunding platforms currently use murabaha (cost plus profit margin) and mudaraba (profit sharing) contracts. Other structures which may be considered includes salam (forward financing transaction), ijara (leasing), and diminishing musharaka (diminishing equity partnership).

Islamic crowdfunding faces challenges at several fronts including:

Lack of knowledge and understanding on how Islamic finance and crowdfunding works. Since crowdfunding is a relatively new concept in developing markets, significant efforts in educating the public about Islamic finance and crowdfunding is not only required but should be the order of the day.

Lack of Regulation. While most governments provide some space for crowdfunding platforms to operate, as long as existing laws are not breached, the absent of regulatory clarity creates some uncertainty and concerns by the public on the legality of the investment platform. It also makes it harder for crowdfunding operators to openly market its services and educate the public.

Takaful

Another important Islamic product that has benefitted the industry and the stakeholders in IBF is Islamic insurance known as takaful. Literally the word means joint responsibility and solidarity. It is based on the concept of cooperation, responsibility, protection and guarantee amongst its participants. Before the introduction of Islamic insurance, Shari’a sensitive investors on the basis of maslaha or darura (necessity) would use conventional insurance. Since then the industry has developed immensely in Muslim-majority countries to offer both family and general takaful, and have also introduced re-takaful companies. A number of developed insurance companies have set up Islamic windows for both takaful and re-takaful to attract Shari’a-sensitive users of insurance.

The idea of takaful is mutual cooperation, where it is based on mutual help amongst the participants, each of them voluntarily contributing to a fund which is used to compensate a member when needed. Islamic law allows measures taken to reduce risk, as evidenced by the hadith where Prophet Muhammed (PBUH) advised a companion to have faith in Allah and tie his camel, rather than just relying on Allah to prevent the camel from running away. The word takaful is not used by all takaful companies. For example, in Sudan, it is while in Saudi Arabia the word cooperative insurance is more often used. Generally, takaful and conventional insurance share the same objective, i.e, to help those affected by a calamity. Hence, insurance started as not for business but a way to help the needy on gratuitous basis. Although takaful and conventional insurance is the same, they differ in their operations and management of funds.

While mutual or cooperative insurance is owned and managed by its own members, takaful on the other hand could be operated by joint stock companies. Hence, it is also argued that takaful in essence may not be purely mutual, in fact most of the takaful companies have resorted to shareholder model-based or commercial entity instead of pure cooperative or mutual organization. They are operated as the commercial entity making profits for the shareholders and this may not render the takaful invalid as takaful companies only act as a mediator to manage participants’ funds and receive remuneration for their services. Hence, it does not have any right towards takaful funds and also does not take responsibility of any deficiency. There are two contractual relationships in takaful: tabarru – voluntary donations – amongst the policy members; and wakala – agency or mudaraba-based profit sharing between the participants and the operator. Further, the funds in the agency or mudaraba contract are invested in Shari’a-compliant avenues to generate a return.

Overall the growth prospects for takaful industry are very positive. Global takaful assets reached US$38.2 billion in 2016 with Saudi Arabia as the largest takaful market holding 48% of global takaful assets. In Southeast Asia, Malaysia dominates the takaful market with asset size of US$7,023.6 million as at first half of 2016 (US$7,324 million in 2015). In the GCC, the takaful sector saw significant premium growth over recent years as health insurance across the region was made mandatory. In addition, some markets, particularly Saudi Arabia, have seen strong tariff increases as a result of the introduction of actuarial pricing guidelines. However, as more policies are adequately priced, premium growth has slowed in line with the economy at large. In the first half of 2016, year-on-year premium growth for takaful companies in the GCC slowed to about 4% from 10%.

Islamic Project Finance

Islamic project finance has grown in significance and is now widely used to finance large, longer-term infrastructure and power generation projects, especially in the Middle East region with a main focus on the GCC countries. The development of such capital-intensive projects on a larger scale began only in the earlier part of this century, fueled by high oil prices in some of the resource-rich GCC countries. In these countries, the need to build oil and gas extraction, transport and refining capacity pushed the demand for Islamic project finance. Islamic finance made up nearly 45% of the total project finance market in the GCC in 2016, compared to just over 12.5% in 2006.

In developing countries such as Africa and Pakistan, growth of Islamic project finance was driven mainly by the increasing need for electricity and water desalination stations. Whereas in the Asian region, Islamic project finance served the financing needs of infrastructure development projects (mainly public infrastructure such as transportation, communication, sewage, water, electricity) that are both capital-intensive and long term (20 to 30 years) in nature.

This niche segment of the Islamic financial industry has yet to develop its full potential to become a mainstream mode of financing despite the growing appetite for infrastructure investments in Muslim-dominated countries. While large-scale infrastructure development projects have been the domain of governments and multilateral institutions; the private sector has emerged as a major source of infrastructure financing in recent years. The surge in private project financing especially in infrastructure development as a result of a renewed government focus and a tremendous growing appetite for infrastructure investments has created major opportunities for Islamic banks and institutions. The Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) estimates that approximately US$71 trillion would be needed globally by 2030 for investments in roads, rails, telecoms, electricity and water infrastructure. In the GCC region and emerging markets, approximately US$2 trillion and US$21 trillion, respectively would be required for infrastructure investments in the next decade.

Deposits

Shari’a-compliant deposits constitute the largest proportion of Islamic banks’ liabilities on their balance sheets. Like the conventional banks, deposits are money due to depositors, which represent funds accepted from the general public for safe keeping, demand deposits (fixed and notice) and foreign currency deposits. In an Islamic bank all these products are designed and operated in a Shari’a-compliant manner. This is one of the most important products in banking management as a change in the level of deposits in the banking system is one of the most important variables in influencing the monetary policy of the country as growth in money supply is usually calculated using total deposits in the banking system. It further contributes to an increased fiduciary relationship as it also provides means of multiplying funds through the strong guarantees derived from the element of trust in banks.

There are different types of deposits structured on the basis of different contracts. Some are merely based on the principle of loan (qard) while others like investment accounts may be based on mudaraba where the profit as well as the principle is not guaranteed by the bank. This can also create moral hazard as Islamic banks may be willing to take more risk, as the investment account holders may be ready to absorb losses in case the bank fails to generate the desired returns. Other major types of deposits offered by Islamic banks include savings accounts, current accounts, term deposits and investment deposits.

Savings Accounts

Generally based on the concept of qard, wadia and mudaraba, it is a type of account that allows customer to deposit and withdraw their money, whenever required. Unlike a demand deposit, it does not have any withdrawal limitation and hence the funds can be withdrawn and deposited at any time on customer’s demand. A saving account holder, unlike a current account holder, does not receive a cheque-book and hence money can be withdrawn from the cash counter or via an ATM machine.

Current Accounts

Unlike a saving account, current account is a non-interest-bearing bank account that allows the deposit holders similar benefits to the saving account and also offers a cheque-book facility. In addition, the current account holder may also have an overdraft facility, which may allow the deposit holders to withdraw more funds than otherwise available in the account.

Term Deposits

Term deposit is a type of deposit that is held at the bank for a fixed period. It is generally of a short-term, with maturities ranging from a month to a few years. A term deposit holder has to agree with the terms that the funds may not be available to the deposit holder until a fixed period after a predetermined notice period. Typical underlying contract at an Islamic bank for term deposit includes unrestricted mudaraba or wakala, where the bank acts as a partner or agent to invest the funds in a Shari’a-compliant manner. The returns of the term deposits are shared with term depositors and the bank (in case of mudaraba), while the returns in the case of wakala agreement are fully passed on to the depositors, and the agent or wakeel receives a fixed wakala fee.

Profit Sharing Investment Accounts (PSIAs)

PSIAs refer to deposits structured around a mudaraba contract where the depositor is known as Investment Account Holder (IAH). The bank agrees to share the profit generated from the assets funded by the PSIAs, based on an agreed profit-sharing ratio, while the losses will be borne by the IAH holders. There are two types of PSIAs: unrestricted and restricted. The former allows the bank or financial institution full independence to invest the funds wherever they like as long as the venture is in compliance with Shari’a. The latter allows investment in only those assets that are otherwise allowed or stated by the IAHs. The funds are managed separately compared to other deposits of the Islamic banks.

Islamic banking deposits have growth in Muslim as well as non-Muslim majority countries and is leading the development of Islamic banking and finance industry. The size of Islamic banking deposits is increasing at different rates in various countries and now accounts for considerable size, for example: the size of Islamic banking deposit in UAE is 25% of the total Islamic banking assets, in Bahrain it is 24%. Bangladesh with 20% of Islamic banking deposits is another major player, while in Pakistan Islamic deposits have exceeded the 10% mark compared to the total banking industry.

Islamic Microfinance

Islamic microfinance has become a rapidly growing market, providing access to financial services to millions of poor people who are at the moment not served by conventional microfinance. Taken in this context, Islamic microfinance is an important instrument for poverty alleviation and an effective strategy to achieving financial inclusion. Over the past decade, Islamic microfinance has emerged from a market niche to a rapidly growing industry worldwide. The focus of Islamic microfinance institutions has over the years shifted from just providing microcredit to offering an array of financial products that serve the growing needs of the poor such as savings, insurance and investments.

An estimated 300 Islamic microfinance institutions (IMFIs) are currently operating in over 18 countries and serving about 14 million active customers of which about 82% are living in Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Sudan. Despite its importance, this niche sector of Islamic finance has yet to reach scale as Islamic microfinance industry accounts for less than 1% of the global microfinance outreach. With 1.2 billion of global population living below the poverty line (i.e. living on less than US$2 per day) and of which 44% of them are concentrated in Muslim countries, Islamic microfinance is set to record a double-digit growth rate of 20% over the period 2015-2018.

Islamic microfinance is defined as provision of microfinance services in compliance with the Islamic law, and is coherent with its moral values of brotherhood, solidarity and caring for the less fortunate. It is a developing industry and is a synthesis of two industries; microfinance and Islamic finance is expected to develop into a vital industry for the poor and less fortunate who are at present avoiding conventional microfinance services due to religious reasons. Islamic microfinance can be involved in four main types of productive services:

Providing access to financial products based on murabaha, salam or equity-based financing in the form of mudaraba, musharaka and ijara;

Providing asset-building products – saving accounts, current accounts and investment deposits;

Providing safety net products – micro takaful; and

Providing social services – charity-based contracts such as qard hasan, zakat funds, sadaqa and dedicated waqf.

In the literature on Islamic microfinance, operating instruments have also been defined under two categories namely, charity-based microfinance instruments that include structures like zakat, sadaqah, charity and qard hasan; and profit-based microfinance instruments that include partnership-based contracts, murabaha, salam, istisna contracts, etc. In partnership-based contracts like mudaraba and musharaka, the risk assumed by Islamic microfinance institutions are presumed to be high. Under such contracts, profits are agreed upon while the losses are shared in proportion of the capital provided. In the case of mudaraba all losses will be borne by Islamic microfinance institution while in the musharaka contract it will be shared with the partners. These modes are not often used by the Islamic microfinance institutions, as there is a preference for microcredit modes. This is due to information asymmetry problems and moral hazard where the partner or borrower has the incentive to undertake lower effort that reduces the probability of the success of the micro project.

According to a research paper approximately, 75% of the total active financing in Islamic microfinance is on the basis of murabaha, while 22% is on the basis of qard hasan. Partnership-based modes financing like mudaraba and musharaka are rarely used. Unlike the Islamic financial services industry that is mainly driven by Malaysia and GCC countries, Islamic microfinance is active and has emerged in developing countries. It has achieved interesting scalability in countries like Pakistan and Bangladesh in South Asia, Indonesia and Malaysia in the South East Asia or Far East and Sub-Saharan Africa and Sudan. Islamic microfinance institutions are found in more than 15 countries including Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Indonesia, Bahrain, Egypt, Lebanon, Iraq, Jordan, Palestine, Sudan, Yemen, and Kosovo. Yet it has grown at a slower pace compared to its conventional counterpart and represents less than 1% of IBF.

The total number of clients benefitting from Islamic microfinance services are estimated to be 1.28 million of which more than 80% are concentrated in Bangladesh, Indonesia and Sudan. The Islamic microfinance industry is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of about 20% between 2014 and 2018. Bangladesh leads in terms of the most number of Islamic microfinance clients, followed by Sudan while Indonesia leads in terms of outstanding dollar amount followed by Lebanon and Bangladesh. There are now important Islamic microfinance institutions set up in a number of countries; institutions that have received prominence lately include:

- Akhuwat: A micro-lending institution based in Pakistan established in 2001. It has since then benefited more than 500,000 clients. With a strong federal and provincial government support Akhuwat is playing a key role in transforming the lives of people in the country through the use of qard hasan.

- Baitul Mal wa Tamwil: Set up in 1993 in Indonesia as a religious institution, it was introduced by an Islamic organization to help facilitate business activities of its members. It was registered as a cooperative. Like Akhuwat it also uses qard hasan mode of financing, in addition to murabaha. It has now more than 3,000 branches throughout Indonesia.

- Family Bank (banking model): Established in 2009 in Bahrain (a country with a very small population and even smaller number of poor people) and operates as a micro-lending bank. As a commercial entity it works with Garmeen Trust as a strategic partner. The programme disburses loans of between US$100 to US$500 while commercial loans are between US$500 and US$5,000.

Home Financing

Islamic home financing, like deposits, is one of the most important retail banking products introduced by Islamic banks. Retail banking has always accounted for the largest component of financing activities. The products offered through retail banking include home financing, car financing and personal financing. In terms of financing concept, Islamic banks have developed instruments on the basis of murabaha, musharaka, ijara, qard hasan and many more, which are compatible with Shari’a. Before the introduction of Islamic home purchase plan, Shari’a-sensitive clients had very limited choice of owning houses. Hence, some had to rent it out while others choose to follow the opinions of Shari’a scholars, which allowed buying one house through conventional financial services on the basis of darura (necessity).

The main difference between Islamic and conventional home financing is inherent in the underlying contracts used. In a typical home financing deal in conventional banking, the bank will lend a sum to the borrower on interest. On the other hand, in a typical sale based contract, an Islamic bank will buy the property from the seller and then sell it on to the borrower or person seeking home financing at a higher price on a deferred sale basis. The typical underlying sale based contract used is bai’ bithaman ajil (BBA), which is based on a Shari’a concept of deferred payment sale. The term BBA is more commonly used in Malaysia and Brunei, while term bai’ mu’ajjal is more common in South Asian region and murabaha in the Middle Eastern countries.

The other contract used in home financing is musharaka mutanaqisa or diminishing musharaka. It is a hybrid contract and is defined as a form of partnership in which one partner promises to buy the share of the other partner gradually until the title of equity is completely transferred to him. The transaction typically has three steps. First, the bank and customer enter into a partnership contract. Second, they enter into an ijara contract where the customer agrees to rent the banks undivided share in the property. In addition, throughout the contract the customer agrees to buy the share of the bank through a sale, so that every time the customer makes a payment, some of the payment is allocated to buying bank’s share in the property. The diminishing musharaka contract is commonly used for asset finance, property venture and working capital. Al Rayan Bank (formerly known as Islamic Bank of Britain) and HSBC Amanah (no longer in operations) based in the UK used this form of contract for their home purchase plans. Some other contracts used include an ijara muntahiya bi al tamlik, which is based on the concept of ijara where the customer leases the house from the bank and it ends with the purchase of the house.

Private Equity

Private equity is a medium to a long-term high-growth investment product that provides equity stake in an underperforming company (not listed on the stock exchange) and has limited ability to raise capital. Private equity investors achieve growth by working with the company’s management team to improve performance, provide strategic advice, and drive operational improvements. As stated in GIFR 2010, the term private equity represents a diverse set of investors who take a majority equity stake in private limited liability companies with a view to increase value upon exit. There are three types of private equity activities:

Venture Capital: The funding of a new business, generally at an early stage that is unable or do not prefer to source funds from a bank;

Development Capital: Investments in an established business to assist them in expanding; and

Buy-out: Funding the purchase of an existing business where there is scope of further improvement.

Islamic private equity works along the same strategies and aims as its conventional counterpart. This means the investment has to be well diversified across different asset classes and geographies. However, the difference lies in how the investments are approached. The Islamic private equity approach to investments is largely driven by Islamic injunctions related to Islamic economics and finance rooted in Shari’a. The second difference is the governance structure of the Islamic private equity where an extra layer is added through a mandatory Shari’a supervisory board.

Further, on the investment side Islamic private equity investments have to ensure that the businesses they invest in are involved in Shari’a permissible activities i.e. avoiding businesses including gambling, pork and alcohol production and selling, adult entertainment, conventional banks and financial institutions and other unethical businesses. In addition, the capital structure of the businesses need to be considered as they should not be heavily involved in interest-based transactions (both on the income and payments side)- this is usually captured through interest-based debt to market capitalization, cash and receivables to market capitalization and interest-based investments to market capitalization. However, if the financial ratios are at an unacceptable level – the investor can agree on restructuring the non-Shari’a aspects of the businesses with the Shari’a supervisory board.

Depending on the type of prohibited assets, usually the board would allow up to three years after taking control to remove financial prohibition. Hence, in order to undertake this, Islamic private equity investor usually seeks a majority shareholding in the target in order to ensure smooth transition from Shari’a impermissible activities to Shari’a permissible. Some of the major changes that will be brought by Islamic private equity to target will include, conformity of legal documentation to Shari’a, phasing out Shari’a non-permissible activities, freezing and phasing out of interest-based debt, and alignments of all relationships (including shareholders) with Shari’a.

Conclusion

The Islamic banking and finance industry has grown tremendously, from the beginning with no product availability five decades ago to an industry that has set a solid foundation in the wider banking and finance industry. The product availability has seen remarkable growth with Shari’a-compliant alternatives available for most of the conventional products including derivatives, futures and options. There remain challenges to enhance these products as the industry grow widely and as the product availability in conventional banking and finance is expanding. Needless to say that there is criticism of the existing products that they are mimicking conventional products and that they are not designed and developed in the spirit of Shari’a.