The central pillars of global financial system have endured a persistent scrutiny in the wake of the continuous changing international economic and political environment. Islamic financial institutions are demonstrating resilience as the world events continue to reshape the landscape of global financial services. The key matter, however, will be the way through which Islamic banking and finance (IBF) industry prepares itself for the opportunities and challenges posed by such a changing global economy.

IBF has demonstrated a remarkable growth, outpacing the growth of its conventional counterparts. Despite the fact that growth has admittedly declined for four consecutive year, going down to 6.02% in 2017, the industry potential remains on the side of buoyancy in the medium to long run. Such data is based on disclosed assets by all Islamic finance institutions (full Shari’a-compliant as well as those with Shari’a ‘windows’) covering commercial banking, funds, sukuk, takaful, and other segments. The aggregated data given in Table 1 are mostly taken from primary sources (regulatory authorities’ statistical databases, annual reports and financial stability reports, official press releases including some other external bodies such as the Islamic Financial Services Board and General Council for Islamic Banks and Financial Institutions.

Despite a rather ambitious growth projection, it was understood that the year 2017 marks the fourth consecutive year of stagnant asset growth of the global Islamic financial services industry. The slowdown largely stemmed from an adjustment in the value of global Islamic banking assets in US Dollar terms on the back of exchange rate depreciations in key Islamic banking markets (e.g. Iran, Malaysia, Turkey, and Indonesia). For other factors contributing to the slowdown, please refer to Chapter 2 of this report.

Table 1:

BREAKDOWN OF IBF BY SECTOR AND BY REGION (USD BILLION, 2016)

| REGION | ISLAMIC BANKING | SUKUK OUTSTANDING | ISLAMIC FUNDS ASSETS | TAKAFUL CONTRIBUTIONS | TOTAL |

| ASIA | 266.158 | 207.8505 | 34.034 | 6.3 | 4.2 |

| GCC | 783.89 | 131.274 | 38.896 | 13.5 | 0.5 |

| MENA (EX-GCC) | 656.28 | 18.2325 | 0.5 | 8.6 | 11.5 |

| OTHERS | 116.672 | 7.3 | 23.8 | 1.9 | 8.1 |

| TOTAL | 1,823 | 364.65 | 97.24 | 30.31 | 24.31 |

Source: Cambridge IFA

By the end of 2017, the global Islamic banking assets were recorded at US$1.823 trillion and the sector continues to dominate the global IFSI, representing 75% of the industry’s assets. The sukuk market, however, reversed its earlier decline and sukuk outstanding expanded to close at US$364.65 billion as at end 2017. The widening budget deficits in key developing and energy-exporting countries encouraged a flurry of fund-raising issuances in 2016, including debut sovereign sukuk issuances by Jordan and Togo. This led to further growth in 2017. The gross contributions in the takaful sector have also increased to close at US$30.31 billion and represented 1.23% of the global IBF. Overall, IBF assets are still heavily concentrated in the Middle East and Asia, although the number of new markets is increasing.

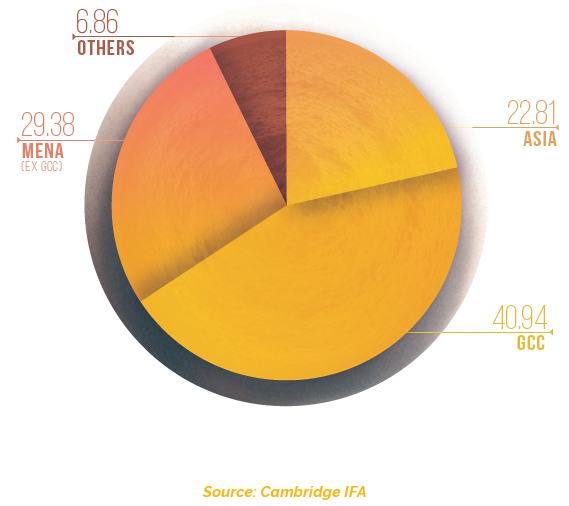

Unsurprisingly, the GCC region accounts for the largest proportion of global Islamic financial assets (with 40.9% of the total) as the sector sets to gain mainstream relevance in most of its jurisdictions. The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region (excluding GCC) ranks a close second, with a 29.37% share, buoyed by Iran’s fully Shari’a-compliant banking sector. Asia ranks third, accounting for 22.81% of the global total, largely spearheaded by the Malaysian Islamic finance marketplace. The contribution from the other regions, particularly Europe and Sub-Saharan Africa, remains modest, although the future growth prospects are promising, given the recent developments and initiatives in several new and niche Islamic finance markets.

In recent years, regulatory developments concerning the Islamic banking sector were witnessed in Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Morocco, Tajikistan and Uganda, among other jurisdictions, each at a different stage of enacting its regulatory regime. Similarly, the Sukuk sector was of much stakeholder interest, with the primary sovereign Sukuk market debuts of Maldives, Senegal, South Africa and the Emirate of Sharjah (UAE), as well as sovereign debuts by conventional financial centres such as Luxembourg, Hong Kong and the United Kingdom.

Inevitable Shift towards the East

Such astounding growth and development prospects, one way or the other, have accelerated the eastward shift in the world’s economic “centre of gravity.” Economies of the Middle East and Asia, as a result, are inevitably seen as vital. The Group of 20 (G20) – a summit that plays a key role in international economic policy – now includes three OIC member countries (Indonesia, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia).

The eastward shift, hence, creates numerous opportunities for Islamic finance industry. These include managing the savings and wealth being created, supporting ongoing economic growth by providing financing, and exercising increased influence in global forums and decision-making bodies. These global forums include both forums that have traditionally been dominated by Western economies (such as the G20, International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the World Bank) and new forums that provide greater focus on emerging economies in the Middle East, Asia, and Africa.

Investigating from the viewpoint of the significance of the oil sector, countries within the MENA region can be classified into oil-exporting and oil-importing countries. It doesn’t come as a surprise that all GCC states belong to the former group; while Egypt, Jordan and Lebanon are in the latter. Amongst the GCC states, Saudi Arabia has the highest proven oil reserves and is thus the most oil-dependent economy. Bahrain, on the other hand, has minimum reserves, with oil contributing approximately 26% to its gross domestic product GDP.

With shrinking oil resources as well as the realization that an oil-based economy cannot be sustained over the long term, the six GCC countries have followed the strategy of economic diversification. Typically, the lack of a diversified economy is characterized by three main categories—the oil sector’s contribution to GDP, its share of total exports and share of government fiscal revenue. In an attempt to amplify such a realization, Saudi Arabia recently launched a breakthrough initiative, namely the 2030 vision1. The latest development in Saudi Arabia for instance, is the operationalization of VAT effective from 1 January 2018.

Many would argue that the magnitude of economic progression in the years to come is likely to be adversely impacted if a diversified economic model is not pursued. As such, the penetration level of Islamic finance to other non-oil sectors may seem to be hindered although the potential of non-oil sector cannot simply be taken lightly.

A study on economic interconnectivity in GCC countries shows that there are sizeable positive spillover effects from non-oil activity in Saudi Arabia.2 The model demonstrates that a one percent increase in Saudi non-oil GDP is estimated to increase GDP in its neighbor countries such as Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and in other GCC countries by between 0.2 and 0.4%. This also shows an enormous potential in which Islamic finance can play its role in the non-oil sector, especially when taking into account its faster average growth in the region.

Since 2008, the world has also witnessed waves of successive financial crises. Ranging from institutional crises (e.g. the failure of Lehman Brothers) to systemic crises (e.g. the virtual collapse of European debt markets) to sovereign debt and currency crises (e.g. fundamental challenges to the euro-zone), the very pillars of the global financial system have been shaken up. The ongoing financial crises have certainly brought back discussions of the sustainability and existence of the conventional financial system. This creates an unprecedented opportunity for the IBF industry to contribute to a global dialogue on the very nature of a robust and resilient financial system, which would hopefully generate a developmental impact on the society.

This opportunity has been further bolstered by the increased clout of member countries (three of which are members of the influential G20) and the active attention the industry has already received in international commentaries on the financial system. Some observers believe that IBF has not played a sufficiently active role in the dialogue – further underscoring the present opportunity. Indeed, contributing to the global dialogue has the potential to not only boost the IBF industry itself, but also pave the way for it to have a genuine impact on the broader financial system by sharing and transferring valuable principles.

What is the Current Outlook?

Many are of the view that the IBF industry commenced with an introduction of Islamic banks in the mid-1970s. In its infancy, the operationalization of Islamic banks were under-pinned by the principle of a two-tier mudaraba whereby on the liabilities side of the balance sheet, the depositor would be the financier while the bank the entrepreneur. On the assets side, the bank would be the financier and the person seeking funding the entrepreneur. Currently, however, the bulk of assets and liabilities are predominantly inhabited by murabaha modes of finance (except Pakistan, where Mudarabah share has increased results).

Following a four-stage evolution, composed of four distinct phases: 1) the early years (1975- 1991); 2) the era of globalization (1991-2001); 3) the post-September 11, 2001 period; and 4) an era after the 2008 global financial crisis; an important question begs for an investigation, ‘where does the IBF industry currently stand?’.

IBF from the Perspective of Microeconomics

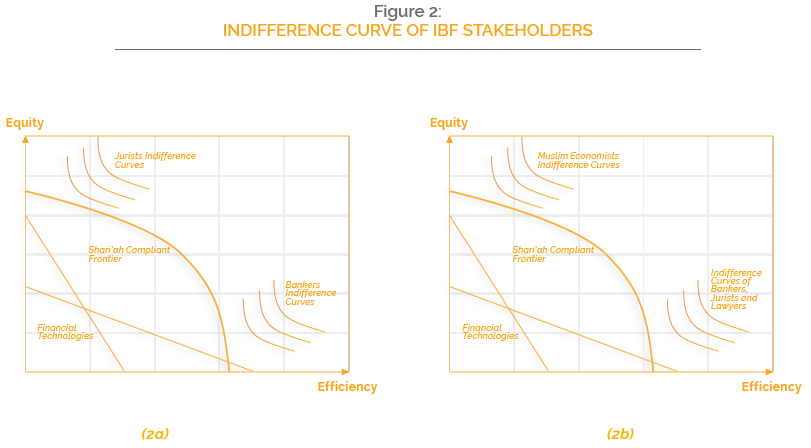

In order to address this question, let us first revisit El-Gamal’s depiction on how IBF has been shaped over time.3 Using a microeconomic analysis, as shown in Figure 2a, he portrays the indifference curves of fuqaha (jurists) that are assumed to be geared towards equity (al-‘adl) relative to the weight given to considerations of economic efficiency (al-kafa’a al-iqtisadiyya). El-Gamal contends that such indifference curves by jurists are based on the manifestations of their understanding of the objectives of Islamic law (maqasid al-Shari’a). In contrast, it is assumed that the preferences of bankers are more biased toward considerations of efficiency relative to those of Islamic jurists. Hence, the latter preferences are drawn more vertical than the former.

The nature of different preferences between jurists and bankers are clearly depicted in Figure 2a, which shows the trade-offs in any economic system between efficiency (the size of the economic pie to be shared by economic agents) and equity (how justly, and how equally, the pie shares are determined). Another element in Figure 2a and 2b is financial technologies that render certain types of contracts and transactions feasible. Each technology allows for linear trade-offs between efficiency and equity by simply allowing for redistribution schemes. The Shari’a boundary, namely Shari’a-Compliant Frontier is drawn as a convex set. This is to signify the Islamically permissible set of allocations within the frontier.

While El-Gamal’s analysis is insightful at the time, such a delineation may no longer reflect the current preferences of IBF stakeholders. It is argued that the jurists have become more pragmatic in their approach and therefore, their indifference curves are believed to have shifted more towards efficiency (see Figure 2b). What makes things more interesting is the bulk of indifference curves located at the southeast region of Figure 2b do not only correspond to jurists, but also denote the preferences of bankers and lawyers.

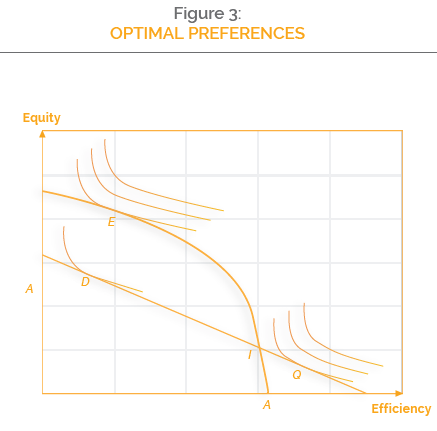

The explanation is very simple and straightforward. The bankers need Shari’a scholars (who also are the employees of the banks) to endorse their products; subsequently, they will need lawyers to make their products legal so that they can be offered in the market. Moreover, with the evolution of financial technology in response to the secular financial needs of economies worldwide; it tends to cater to the bankers, jurists and lawyers preferences. Thus, producing the status quo tangency point Q, in the south-east part of the figure, which affords society a high level of economic efficiency, at the expense of low levels of equity (shown in Figure 3). Muslim economists, in contrast, who are now known as being more concerned about the realization of maqasid al Shari’a aim to describe and analyse the point that is optimal to Islamic economics and finance, that is the tangency point E (shown in Figure 3).

Nonetheless, recognizing the difficulties surrounding the development of a financial technology that passes through the ideal point E, Muslim economists may compromise by turning to point D, at which the preferences are maximized subject to the current financial technologies constraints; although this point can easily be viewed as socially inefficient.

Point I, located at the intersection of the current financial technology and the permissibility frontier, is perhaps closer to the current reality of the IBF industry as it may be relatively easy to accomplish. This is due to the increasingly prominent role of Shari’a scholars in driving the era of Islamic financial engineering. It is therefore considered important to understand how the process of Shari’a minds work, as deliberated upon in the following section.

Reflecting on the Algorithm of Shari’a Minds

There are, at least, four (4) fiqh legal maxims or foundations upon which the jurists develop their arguments or opinions;

- Al Taysir al-Manhaji; which can be defined as opting for the ‘light’ opinion (at-taysir) but is still within the methodology (manhaj) of fiqh. However, this method cannot be over used (al-mubalaghah fi al-taysir) since it could lead to the attitude of ‘taking things too easy or too lightly’ (al-tasahul). One may encounter a circumstance where a light opinion (not strongly narrated) is preferred to a methodological sound opinion due to its benefit (maslahah) that is considered to outweigh its harm (fasad). According to the National Shariah Council Indonesia, this approach cannot be justified.

- The basic principle of Al Taysir al-Manhaji is “to make use of a strongly narrated opinion that carries maslahah (benefit); should it not be viable, any less strongly narrated opinion driving certain maslahah can be adopted”.

- As a result of (a), there is a possibility to revisit the light opinion issued by the old generation of fuqaha; due to its relevance and benefit for the contemporary practice of muamalah.

- Other examples include two views;

- Substance over Form (al-maqasid wa al-ma’ani): the objective or meaning is what will determine the validity of the contract; not the form of articulated words.

- Form over Substance (al-alfazh wa al-mabani): the factors that determine the validity of the contract is the form or how the words are articulated, not its objective or meaning.

Despite seemingly to be contrary, both are adopted by the National Shariah Council Indonesia in determining fatwa, depending upon its relevance and benefit (maslahah). The application of the first view (substance over form) can be found in the practice of wadi’ah deposit; wadi’ah is the form (al-alfazh wa al mabani), but the substance (al-maqasid wa al-ma’ani) is essentially qard. This is due to the feature of wadi’ah that allows the custodian (person or entity) to use and replace it (typically mithliyyat) with another asset/com- modity which has a great deal of similarities and equivalent value. This feature, in essence, constitutes a qard contract.

The example of the second view (form over substance) appears in the application of bilateral wa’ad (muwa’adah). At the outset, it has similarities with a contract (aqad), since both are binding. Nevertheless, one of the primary differences is that muwa’adah does not entail right and obligation to the contracting parties as opposed to a contract.

- At-Tafriq Baina al-halal wal haram or differentiating the halal (permissible) components from its haram (impermissible) components. It is commonly under- stood that in the event of commingling between halal and haram, the haram component is perceived to displace the halal element; hence overwhelm the blend. The typical verdict, therefore, suggests that the mixture becomes haram (impermissible). As such, the fiqh legal maxim says ”idza ijtama’ al-halal wa al-haram ghuliba al-haram”.

The contemporary fuqaha are of the view that this can not necessarily be the case for the commercial transaction (mu’amalah). Wealth or money in this respect, is not haram by definition. What determines the permissibility or impermissibility of money is not due to its material or substance; rather, it is contingent upon how the money is generated. Consequently, the source of income flow from which the money is generated can be mapped and identified.

Ibn Shalah as quoted by as-Suyuthi in Al-Asbah wa al-Nadzair states:

“If halal and haram money commingled, the way out is to segregate the haram money and return it back to its owner. If the owner is unknown, the money can be donated”.

This is similar to Ibn Taimiyah’s opinion in his Fatawa Ibn Taimiyah:

“Whosoever’s wealth is constituted as halal and haram, the latter should be cleansed out and the rest should be halal for him.”

The application of tafriq al-halal ‘an al-haram technique has been widely demonstrated in the establishment of an Islamic window, whereby the mother company is still purely conventional.

- I’adah al-nazhar; this is a fiqh method by which former fiqh opinions are revisited. Such an effort is carried out to seek the relevance and benefit (maslahah) of the old verdict, which can be deemed to be no longer factual with the contemporary phenomenon. In doing so, not only is the ‘illah or ’cause’/’underpinning reason’ re-examined, but it also opens the door for the consideration of a ‘weaker’ or ‘lighter’ fiqh opinion due to its benefit (maslahah).

For example, some scholars are still perceived to constantly hinge on to the view that a letter of guarantee under a kafalah contract would not generate any fees. According to some contemporary scholars, if fees are to be imposed, it should be based on actual expenses and fixed amount, instead of a percentage. This is the view of the majority of past scholars, disallowing the fee for a kafalah contract, which is evident in most Islamic law books and literature. The basic argument for this stand is the fact that a guarantee is an act of charity or a kind of social help in the community and surely, any act of charity cannot be levied with any fees. A very convincing argument indeed.

Nowadays, though the letter of guarantee has taken a new shape, some modern scholars still view the letter of guarantee issued by many agencies and banks as an act of charity. In the current practice, the guarantor is exposed to huge risks, unlike the traditional way of guarantee in the past. Not only that, a letter of guarantee has become part and parcel of financial and business transactions without which many transactions, especially international trade as well as project financing, will be adversely affected.

In the case of a kafalah arrangement, one contemporary jurist argues that the act of a loan by the guarantor may or may not happen. At the time of entering into a kafalah arrangement, there is no loan being advanced. The act of advancing the loan is post-ante to the kafalah arrangement. Although some scholars have prohibited this on the merit of the juristic technique of sad al-dharai’, which is to block any means or practices which may lead to prohibited practices. In Islamic legal history, this juristic technique is not of the same level of acceptance by all great Shari’a jurists in the past.

- Tahqiq al-manat is a process of analytical insight into examining the underpinning reasoning (‘illah) of a juristic view. The notion of an ‘illah is in fact not new in Islamic legal theory. The basis of a ruling was developed in Islamic legal theory before a similar theory emerged in the English common law system. An ‘illah is something which creates by its effect a Shari’a ruling. In Islamic law, an ‘illah must be an evident, constant and a regular attribute, and having a co-extensive and co-exclusive effect. Islamic legal theory has also developed a very systematic way of finding the true ‘illah or basis of the ruling. This is known as masalik al-‘illah or referred to as “distinguishing” in English common law.

On the whole, the rules laid down by the jurists for identifying and establishing the true ‘illah do not go beyond three stages, namely takhrij al-manat, tanqih al-manat and tahqiq al-manat. There is a compelling need to understand this process, as majority of substantive law in Islam, according to many Muslim jurists such as al-Juwayni and Ibn Taymiyyah, are actually reached through the medium of qiyas or analogy. This is justified and conceivable, simply because the revealed texts are limited, but the incidents of daily life are unlimited and there- fore, it is impossible for something infinite to be enclosed by something finite.

Takhrij al-manat or identifying the probable ‘illah is the starting point in the enquiry concerning the identification of ‘illah. It is an attempt to anticipate all relevant properties or attributes that could be attributed to the original case – which should be mentioned in either the Quran or the Tradition of the Prophet Muham- mad (pbuh) – as the basis of law. What follows is tanqih al-manat, which is to dis- qualify some of the qualities identified in the first process. Technically speaking, tanqih al-manat means connecting the new case (the case that requires a new ruling) to the original case (which is already mentioned in the Quran or the prophetic tradition) by eliminating the discrepancy between them or determining the ‘illah by refining it from irrelevant qualities. The last stage is called tahqiq al –manat, which is to confirm that a particular selected quality or attribute is the actual ‘illah.

Where does the IBF currently Stand?

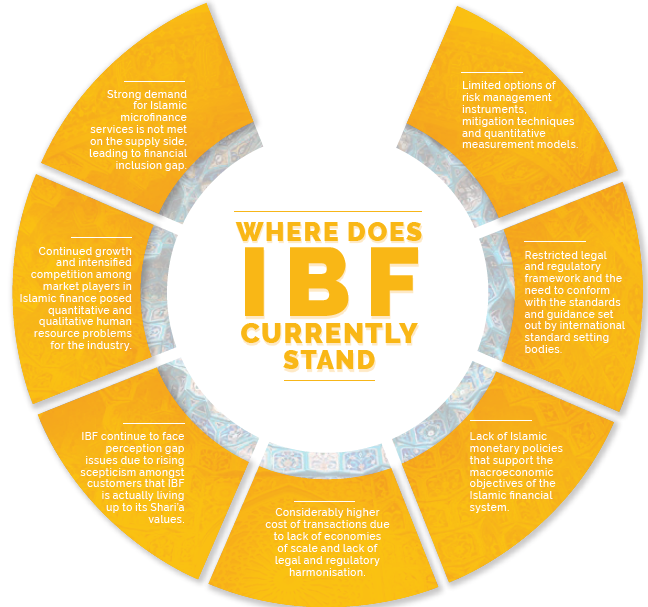

In spite of an impressive progress in the last few years followed by a rather modest one recently, the outlook of IBF is characterized by the followings:

- Considerably higher cost of transactions

Higher cost of transactions is indeed one of the major unresolved issues facing the Islamic finance industry. Some would say that this is due to the economies of scale that the industry has yet to attain. Others might contend that the problem arises because of a lack of legal and regulatory harmonization, which contributed to an uneven playing field leading to higher cost of transactions of Islamic financial products. Notwithstanding such arguments, this requires a solid solution, particularly in the area of home financing, which is considerably ubiquitous in many Muslim countries as well as for Muslim communities living in non-Muslim countries.

- Limited options of risk management instruments, mitigation techniques and quantitative measurement models

Despite the prominent initiatives by the Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB) in issuing guidelines relating to risk management, stress testing and capital adequacy standards; a more detail technical guidance, which features the techniques and methodologies of risk assessment taking into account unique risks in IFIs is still required. Furthermore, it was also commonly understood that whilst the definition of risks in IFIs is not substantially different from those of their conventional counterparts; a modification in the identification, measurement and mitigation may be required due to some Shari’a principles. More importantly, there is a dire need to develop a proper legal environment and a suitable regulatory framework for the sound practice of risk management in IFIs.

In addition, limited liquidity instruments for Islamic capital markets is another challenge. In response to this, the International Islamic Liquidity Management (IILM) had recently launched “Golden Triangle Sukuk”, featuring a connection between financial stability, economic development, and debt management.

- Restricted legal and regulatory framework

A daunting task for stakeholders of IBF is not only to establish regulatory harmonisation between different jurisdictions; but also to conform with the standards and guidance set out by international standard-setting bodies such as BCBS, IOSCO and IFRS. Surely, the idea of ‘one size fits all’ is not viable due to the fact that different countries have different institutional and regulatory frameworks.

- Lack of Islamic monetary policies

At the macro level, the availability of Islamic monetary instruments is indispensable to support the macroeconomic objectives of the Islamic financial system. Another important element of such an instrument is for the purpose of liquidity management. Some countries have initiated the creation of such instruments, such as in Indonesia4 and Malaysia. However, more efforts need to be undertaken to also allow inter-jurisdictional transactions and liquidity management between the countries implementing interest-free financial system.

- Financial inclusion gap

Financial inclusion is a concept that gained its importance since the early 2000s, which initially referred to the delivery of financial services to low-income segments of society at affordable cost. However, distinct features which characterize the concept of financial inclusion from an Islamic perspective are two-fold a) the notions of risk-sharing, and b) redistribution of wealth.6 Although there is a strong demand for Islamic microfinance services in OIC countries, it is, nevertheless not met by the supply. The study shows that although OIC countries have more microfinance deposits and accounts per thousand adults as compared to non-OIC countries, the values of Microfinance Institution (MFI) deposits and loans as a percentage of GDP are still much lower in OIC countries (0.61% and 0.79%) compared with developing countries (0.78% and 0.97%) and low-income countries (0.92% and 1.19%). The gap of microfinance in OIC is not only demonstrated by its limited scope, but also by the lack of regulation in OIC countries compared to other developing countries. In the MENA region for example; only Egypt, Morocco, Syria, Tunisia, and Yemen have specific legislation for microfinance institutions.

- Lack of human capital enhancement

The continuing growth and intensified competition among market players in Islamic finance has certainly posed quantitative and qualitative human resource problems for the industry. It does not come as a surprise, therefore, that the industry needs more and better-qualified personnel, which, unfortunately is rather in short supply. An establishment of visionary polices and initiatives to respond to this matter will definitely be useful. Furthermore, such policies and initiatives are in line with the recommendation no. 5 of “10-Year Framework and Strategies for Islamic Financial Services Industry Development”7, which states ‘develop the required pool of specialized, competent and high calibre human capital.’

- Perceptions about Islamic finance

Many still think that Islamic finance is basically an industry designed by Muslims and offered solely to the Muslim market. Although it appears to be partially the case, nonetheless, the key spirit of Islamic finance is a lot more profound than what has been stated. Take an example of interest (riba) prohibition; it is shared with Judaism and Christianity. It is also interesting to note that charging interest is also prohibited in Buddhism, Hinduism, and many other faiths and philosophies. Another rising issue is scepticism amongst customers that IBF is actually living up to its Shari’a values, resulting in a perception gap. Lack of innovation is why many view Islamic banking products as mirror images of conventional products.

What are the Opportunities?

Despite the existing and foreseeable challenges, the prognosis for Islamic finance seems to be positively validating the assertion that Islamic finance has become mainstream and is here to stay and grow. Renewed interest is being witnessed from the West, as can be seen from the recent announcement by the UK of a sovereign sukuk and a reiteration of the desire by multiple cities to position themselves as the “global hub” of Islamic finance. Within the Middle East, capitals such as Dubai, Doha and Manama remain keen to retain their identity as the centre of Islamic finance. In fact, Dubai has gone one step ahead and declared its intention to become the capital of the Islamic economy. Further afield, Kuala Lumpur remains committed as the trailblazer for Islamic finance and the halal economy. This shift from mere banking and finance to the broader Islamic or halal economy is interesting in that it has not only expanded the size of opportunity manifold, it also proposes to create a link between Islamic finance and the real economy including sectors as diverse as hospitality, media, clothing, food and lifestyle.

In addition to the heightened interest from these somewhat more traditional centres of Islamic finance, the most encouraging signs of the proliferation of Islamic finance are coming from Turkey, Africa, and Central Asia where emerging and transition economies are embracing Islamic finance not only as a means of raising capital for infrastructure projects but as mainstream retail banking, finance and insurance. While Islamic finance remains set for growth and expansion, a trend that can be expected to endure in the short to medium term is the variation of performance across sectors. Banking and sukuk will continue to dominate the industry in terms of size. Islamic funds and takaful, on the other hand, while growing steadily; their growth will remain modest in terms of the overall share. Although some see this as a challenge, this also presents a great opportunity. As the link between the real and nominal economy becomes more pronounced, these sectors are bound to become more prominent.

Another very positive development in the Islamic finance industry is the reorientation towards social objectives and financial inclusion. This is driven by both push and pull factors. On one side, a need is being felt to respond to criticisms that Islamic finance has failed to deliver on its promises of fairness, equity and inclusion. However, there is also a genuine demand and opportunity in the wake of the Arab Spring and the ongoing global recession to redirect innovation towards services and products that can create more economic opportunities, jobs and financial inclusion for those who hitherto have been on the sidelines of the Islamic finance revolution. Islamic microfinance, crowdfunding, SME finance etc. are the buzzwords at Islamic conferences and symposia.

Academicians, researchers and practitioners are now increasingly focusing on developing new and innovative Islamic financial products and solutions that can make a real difference to the common man. Competitions, grants and awards are being established to incentivize the brightest minds to take up the challenge. This trend bodes well for the realignment of Islamic finance with Maqasid al-Shari’a, a critical link that many deemed broken as Islamic finance pursued an agenda of emulating a permissible version of conventional finance with little attention given to the broader purpose and objectives of an Islamic economy.

The Way Forward

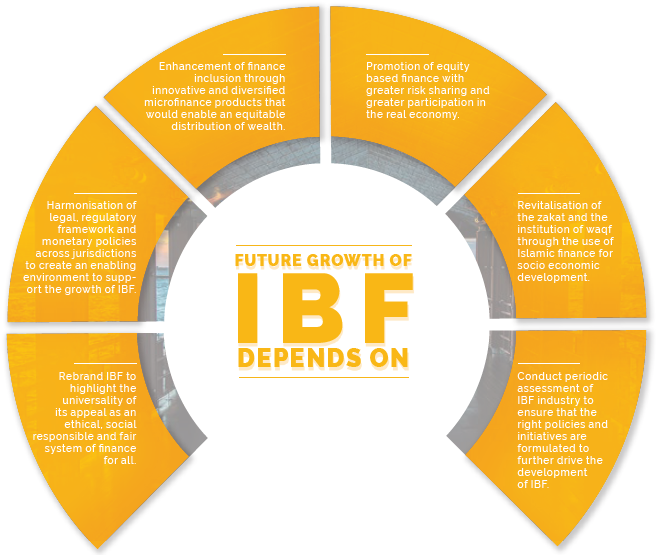

The fact that Islamic finance has been a thriving phenomenon requires further examination in strategizing the policies and initiatives; and more importantly to ensure that the values are preserved and resonated across all components of the Islamic financial system. It is, therefore, suggested that the areas which necessitate particular consideration in the years to come are as follows:

- Promoting equity-based finance and strengthening the linkage between the real and financial sector

Islamic finance may have made significant progress from the early days but so far it has constrained itself mostly to debt-like instruments derived mainly from trade-based contracts such as murabaha, ijarah, istisna’ and salam. With the maturity of the market, institutions and players; the need now is to embrace the true spirit of sharing risk and rewards and move to more equity-based finance. Hence, the development of market infrastructures to support such an initiative can’t be ignored. As a result, this will not only help differentiate and distance Islamic finance from the allegation of “conventional finance in a different guise” but also enable it to serve and expand in areas where it is currently falling short. Greater sharing of risk would inevitably require greater involvement, oversight and participation in the real economy and further development of risk management techniques. But this is exactly what Islamic finance needs to do now.

- Enhancing financial inclusion

The emerging interest and initiatives in microfinance are undoubtedly unwavering. Nevertheless, as described earlier, the so-called ‘financial inclusion gap’ is still somewhat prevalent. Therefore, innovative and diversified microfinance products need to be created and enhanced to allow the underprivileged society to benefit from such endeavors. More importantly; it will also enable an equitable distribution. Concurrently, it also makes a lot of sense if such initiatives are also coupled with the development of takaful and micro takaful sector as part of the cushion component of the Islamic financial services industry.

- Promoting the revitalisation of zakat and awqaf

In recent times zakat and awqaf, unfortunately, are seen as primitive, inefficient and even, in some places, as corrupt institutions that have outlived their utility and failed to deliver to their beneficiaries. It is true that there are significant legal and regulatory challenges to the rehabilitation of these institutions. However, the potential that these institutions possess in terms of reach, diversity and inclusion outweighs any efforts that may be required to bring these back to the mainstream.

In this regard, visionary policies and solid initiatives need to be set out to foster a stronger collaboration among countries and international strategic stakeholders to promote the institutionalization of these redistributive instruments so that the modernisation and rehabilitation of zakat and awqaf as formidable institutions of Islamic finance can be attained. Furthermore, such a transformation is needed to ensure that real change is brought about through financial inclusion.

- Harmonising legal, regulatory framework & monetary policies

At the macro and governmental level, there is now more than ever the need to create an enabling environment to support the growth of Islamic finance. It has been previously highlighted the need for greater harmonization and coordination across legal and regulatory jurisdictions. Equally important are measures by governments that are keen to promote Islamic finance.

- Conducting a periodic assessment of the IBF industry and its impact on society at large

The IBF industry, which started at a modest scale in the 1970s, has indeed demonstrated tremendous growth over the last four decades. It is even dubbed as the fastest-growing industry, having attained double-digit growth in the last few years. As such, this has prompted the question over the factual magnitude of the industry; interconnection and interdependence between sectors within the industry, and more importantly the impact of the industry on the society at large. It is suggested that that various jurisdictions might have different levels of development. In addition, it is believed that various sectors in the IBF industry are growing at different speed. Through comprehensive and methodical assessments, a sound set of policies and initiatives can be formulated to further drive the development and transformation of this industry.

g) Rebranding Islamic finance

The fundamental essence of Islam is its universality and the fact that it transcends time, place and people. The Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) was sent as a mercy to the world.8 Islamic finance in its true form is a financial ideology that is grounded on the principles of justice, fairness, compassion, honesty, equity, sharing and inclusion. These divine principles also transcend time, place and people and as such have been emphasized not only in all Abrahamic monotheistic religions but are cherished across all civilizations and humans. The need therefore is to not highlight the exclusivity of Islamic finance but the universality of its appeal as an ethical, socially responsible and fair system of finance not just for Muslims but for the whole world.

Conclusion

With the above trends poised to continue over the short-to-mid-term, four associated factors will be critical for IBF. First, product innovation that goes beyond tweaking and juxtaposing of existing contracts to look at newer and more imaginative ways of delivering what is being aspired by the market. Islamic financial products should be able to provide a true differentiation and a real value addition to addressing the social and economic challenges faced by the Muslim and wider world.

Second, as Islamic finance expands to new territories and jurisdictions and gets more connected to the global Islamic economy; harmonization of Shari’a, legal and regulatory rules will become even more critical. This is to ensure that cross-border transactions costs are low and the industry is able to be efficient and competitive. This requires governments and regulators to think less in terms of competition and more on the lines of collaboration and cooperation. While regional, national and local variations will exist, these should add to the richness of Islamic finance and not become a hindrance to its proliferation. This, therefore, is not only the biggest challenge but also the greatest opportunity.

Third, the fundamental essence of Islam is its universality and the fact that it transcends time, place and people. Islamic finance in its true form is a financial ideology that is grounded in the principles of justice, fairness, compassion, honesty, equity, sharing and inclusion. These divine principles also transcend time, place and people and are cherished across all civilizations and humans. And finally; as the world currently signs up to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); IBF cannot afford to miss the momentum to prove that it can be part of the process of achieving some of its goals in a meaningful manner, such as poverty eradication and reduced inequalities. This will consequently reinforce the universality of IBF’s value proposition as an ethical, socially responsible and fair system of finance, not just for Muslims but for the whole world.