Introduction

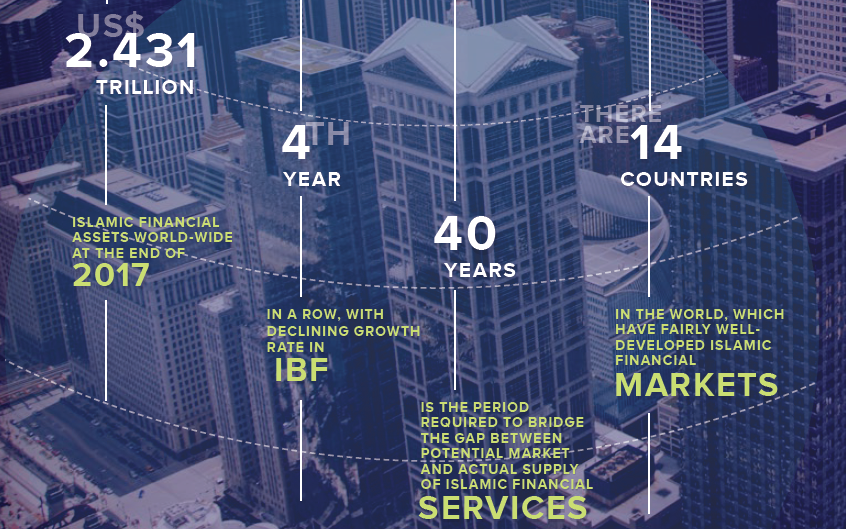

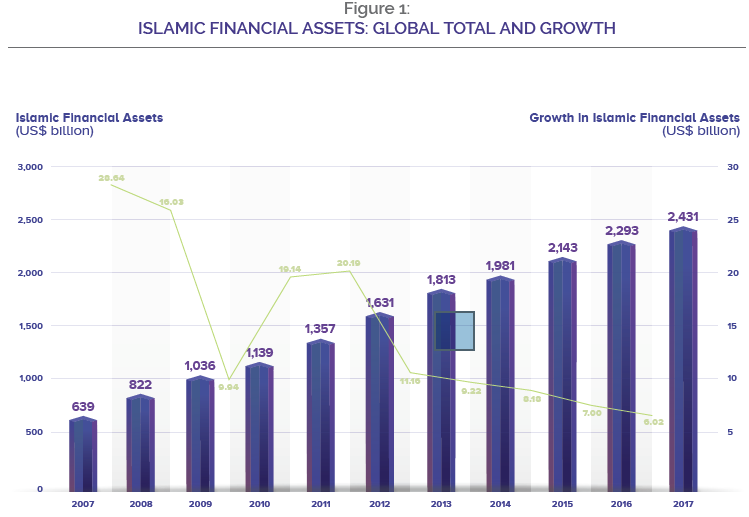

Islamic banking and finance (IBF) is growing in popularity but with a declining trend. The global Islamic financial services industry grew by 6.02% in 2017, from US$2.293 trillion at the end of 2016 to US$2.431 trillion at the end of 2017 (see Figure 1). In dollar terms, there was a net increase of US$138 billion in the global stock of Islamic financial assets.

Banks continue to dominate in terms of global Islamic assets under management (AuM), with 79% of the global Islamic financial assets held by Islamic banks, Islamic windows and subsidiaries of conventional banks. Out of the Islamic banking assets, around 60% are held by full-fledged Islamic banks (US$1.46 trillion in volume).

With the fourth consecutive year of single-digit growth – 6.02% in 2017, compared with 7% last year, and 7.3% and 9.3% in the years prior to 2016 – this is certainly the right time for the industry stakeholders to ponder over the real reasons for slow-down. Is it just a natural and temporary slow-down caused by macroeconomic conditions in the countries where IBF is significant, or are there some fundamental issues that have started biting the industry?

“MOST OF THE GROWTH STEMS FROM ISLAMIC BANKING, WITH ISLAMIC ASSET MANAGEMENT BEING THE LEAST GROWING SEGMENT.”

In the 2016 report, we attributed the slow-down in growth to: [1] political conflicts in a number of Muslim countries; [2] historically low oil (and commodity) prices; [3] receding inter- est of Western financial institutions in the IBF; and [4] natural slow-down in IBF due to maturity of the industry. While these factors continued to contribute to the slowdown, we have identified additional factors that might have contributed to this phenomenon. These include: [A] structural issues; [B] stifled innovation; and [C] wider macroeconomic factors.

“SUKUK MARKET REMAINED SUBDUED, ALTHOUGH IT PICKED UP A BIT FROM THE LOW ISSUANCE IN 2016.”

Structural Issues

The industry hesitates to accept the fact that IBF has failed to develop a value proposition distinctly different from its conventional counterpart. Islamic asset management, where the so-called Islamic value proposition is the most relevant, is unfortunately facing the most serious challenges.

Islamic banks and financial institutions are fast-exhausting the captive Shari’a-sensitive market they have historically relied on to remain profitable. Even in some of the most vibrant markets for IBF, the Shari’a-sensitive segment (those who use Islamic financial services for purely religious reasons) is up to 5% of the market. Therefore, in the markets where Islamic banking has attained a share of one-fifth to one-fourth, the institutions offering Islamic financial services are finding it difficult to win the greater share. Box 1 summarizes results of a quantitative study of longitudinal growth of IBF globally.

Box.1 Longitudinal Growth of IBF Globally

IF WE ACCEPT 1975

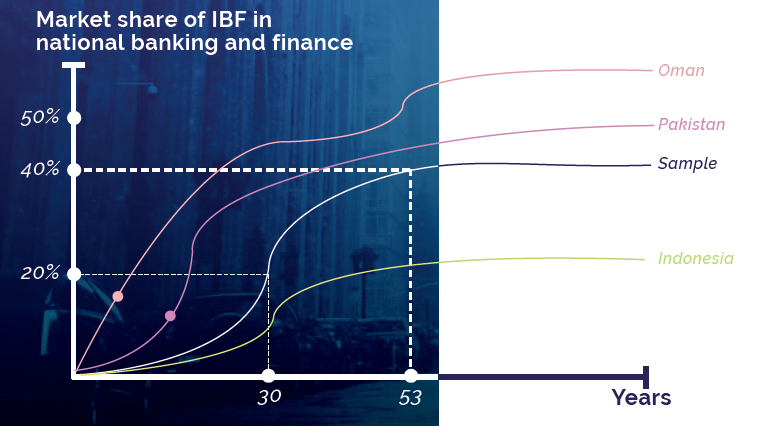

as the birth year of modern Islamic banking and finance, then it took nearly 40 years for the industry to grow its global assets to US$2 trillion. The growth has naturally not been even in all the countries where IBF now exists. Some countries experienced periods of higher growth than others, and hence it took them less time than other countries to capture a market share. Overall, it took the industry 30 years to capture market share of 20% (see Methodological Note below for further details).

The data suggests that the late-entrant countries in the IBF sector tend to move relatively fast toward the 20% market share. It is expected that the new IBF markets in North Africa will hit the 20% target well before the 30 years mark.

Large countries such as Indonesia and Turkey, have failed to capture any significant market share for IBF since the first Islamic financial institution was established therein. For example, Bank Muamalat was established in Indonesia in 1991 and even after 26 years, IBF is merely 5% of the financial sector in the country. Similarly, although Islamic banking (or what is known as Participation banking in Turkey) started in 1983, the current share of IBF in the national financial sector is merely 5%. In other words, it has taken the country nearly 34 years to achieve a meagre market share.

On the other hand side, Bangladesh started Islamic banking in 1983 and Islamic banks have managed to capture over 22% of market share in terms of deposits and investments. Bangladesh, therefore is one example of average (30 year) performance of Islamic banking outside the GCC region.

METHODOLOGICAL NOTE:

We used a sample of 37 countries with incidence of IBF to determine how long it took for the countries in the sample to capture 20% market share in their respective financial markets. Obviously, starting points for each country differed, as IBF was initiated in each country at a different time. For example, IBF started in the UAE with the establishment of Dubai Islamic Bank in 1975, whereas in Saudi Arabia it was in 1988. On average, it may take 30 years for a country to achieve 20% market share for its Islamic financial sector. The countries that are late starter such as Oman, the growth of IBF is rather swift. It took the country less than 7 years to achieve market share of almost 13%, and if the trend continues, its Islamic financial sector may achieve the target of 20% within 10 years. It will be a remarkable performance, and credit must go to the systematic approach the national regulator has taken to the development of IBF.

Pakistan is another interesting story. Although Islamisation of the economy started in the late 1970s, industry analysts considered the year 2000 as the real starting point for IBF in the country when the government decided to pursue the dual banking model. Since then, the growth has been impressive, and it is expected that the country will have its Islamic financial sector capturing 20% market share by 2020.

Unless IBF develops a distinct economic value proposition of its own, this economic value drag will continue to slow down the growth.

This proposition puts the industry on a razor’s edge, as this necessarily implies secularisation of the industry, which most stakeholders in the industry may not accept, at least in the short-run. The focus must gradually shift to economics, albeit not ignoring the Shari’a requirements. For this, one must go back to the drawing board to determine the raison d’etre of the prohibition of interest, and delineate structures that are commensurate with the real requirements.

This leads us to the question: Is there a need for a “correction” in IBF? The correction in this context is not necessarily price-related; rather it is methodological in nature. It should change the direction the industry has taken so far. In our view, there is a need to make 30-degree change in direction at this point in time; rather than suggesting a 360 degree move.

Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) is proposing something similar for Islamic banks to adopt practices, products and conduct that must impact the economy, communities and environment, positively and in a sustainable way. This is a pragmatic approach that would allow BNM to reform IBF in a gradual way.

Stifled Innovation

In the post-financial crisis era, IBF has seen no significant innovation in product development. Islamic banks and financial institutions are merely cookie-cutting around structures like tawarruq and plain-vanilla murabaha. Consequently, the industry is fast approaching stagnation, allowing critics to term Islamic banks as tawarruq houses. Products like Islamic credit cards, Islamic personal finance and working capital financing are in almost all cases based on one or other variant of tawarruq.

The heavy reliance on tawarruq has made IBF akin to conventional interest-based banking and finance. Despite strong juristic rationale and legally convincing opinions on permissibility of tawarruq, Islamic economists remain strongly opposed to the use of this controversial tool in IBF. Its excessive use has conventionalized Islamic banking more than IBF’s attempt to Islamize conventional financial system. The so-called conventionalization of IBF, in view of many, is the main reason for fading interest in IBF.

Admittedly, restrictions on the use of tawarruq (if these are implemented after it has been in practice for sometime) may have two opposing effects: (1) spurred innovation; and (2) depressed growth.

In countries like Indonesia, Pakistan, Jordan and even relatively new markets like Oman and Morocco, where tawarruq is not acceptable, IBF has seen a lot of alternative products and structures. There are all kind of non-tawarruq-based products in such countries. For example, Islamic International Arab Bank (IIAB) in Jordan offers an Islamic credit card based on qard hasan, a variety of microfinance products are offered in Indonesia, and working capital financing products based on musharaka are in use in Pakistan.

Innovation is a medium to long-run phenomenon, and if tawarruq is restricted in the countries where it is rampant at present, it may slow down the growth of the industry. This is due to the concern with liquidity management solutions that remain based on commodity murabaha (CM). Disallowing tawarruq may hamper the process of liquidity management at least in the short-run.

Insufficient Regulation

Despite huge efforts by Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB) and Accounting & Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) to develop regulatory guidelines and Shari’a and governance standards, a number of countries have yet to develop their own regulations for the industry as a whole (e.g., Bangladesh) or for the individual products (e.g., sukuk guidelines in the UAE).

In the absence of a separate regulatory framework for Islamic banking in Bangladesh, the sector has captured over 22% market share in the country. One should assume that this share could have been a lot more had the authorities created a level-playing field for Islamic banking institutions by way of developing a comprehensive approach to IBF. An ad hoc approach is reactive in its very nature, and there is a definite need for the financial regulators to be more proactive where IBF is significant in size and proportion.

Macroeconomic Factors

Adverse movements in exchange rates is one example of the macroeconomic factors that have led to smaller (or not bigger) size of the Islamic financial services industry in the respective countries. Although Iran is presented as one such example, the story is not entirely irrelevant to a number of other Muslim countries.

Potential and Actual Size of the Global Islamic Financial Services Industry Potential size of the global Islamic financial services industry can be defined as the assets under management (AuM) of the institutions offering Islamic financial services to all those who would like to have access to such services, and to all those who would like to use Islamic financial services but have excluded themselves voluntarily from the financial services market because such services are not available (GIFR 2016, p. 39). Actual size of the global Islamic financial services industry is the AuM of all the institutions offering Islamic financial services, i.e., stand-alone Islamic banks, Islamic banking windows and subsidiaries of conventional banks and financial institutions, stand-alone takaful and re-takaful companies, takaful and re-takaful windows and subsidiaries of conventional insurance and reinsurance companies, Islamic microfinance institutions (whether microfinance banks or non-bank microcredit provides), Islamic financial assets held by Islamic fund managers and Shari’a-com- pliant asset management arms of conventional fund management companies as well as outstanding sukuk.

Table 1:

POTENTIAL AND ACTUAL SIZE OF THE GLOBAL ISLAMIC FINANCIAL SERVICES INDUSTRY

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

| POTENTIAL SIZE OF THE GLOBAL ISLAMIC FINANCIAL SERVICES INDUSTRY (US$ TRILLION) | 4.0 | 4.4 | 4.84 | 4.0 | 4.4 | 4.84 | 4.0 | 4.4 | 4.84 |

| ACTUAL SIZE OF THE GLOBAL ISLAMIC FINANCIAL SERVICES INDUSTRY (US$ TRILLION) | 1.036 | 1.139 | 1.357 | 1.631 | 1.813 | 1.981 | 2.143 | 2.293 | 2.431 |

| SIZE GAP (US$ TRILLION) | 2.964 | 3.261 | 3.483 | 3.693 | 4.052 | 4.47 | 4.953 | 5.513 | 6.155 |

| GROWTH IN THE ACTUAL SIZE OF THE GLOBAL ISLAMIC FINANCIAL SERVICES INDUSTRY (%) | 26 | 9.9 | 19.1 | 20.2 | 12.3 | 9.3 | 7.3 | 7 | 6.02 |

| AVERAGE GROWTH RATE BETWEEN 2009-17 (US$ TRILLION) | 11.39 |

As Table 1 shows, there is a growing gulf between potential and actual size of the global Islamic financial services industry. With nearly US$3 trillion of deficit in 2009, the gap has now more than doubled. This implies that the catch-up time required for the industry to realize its potential is ever-increasing. GIFR 2014 reported the catch-up period to be an estimated 17 years, which increased to 35 years last year. With the depressed growth of the industry, this period has gone well beyond 40 years.

What does this mean? Will the industry never be able to realize its potential? If the current situation prevails and no serious efforts are made to re-invigorate the industry, this may very well be the case. However, there are now some scattered efforts to bring a value-base perspective to the industry (e.g., BNM’s recent plans to focus on value-based intermediation in the context of IBF). Such initiatives on part of the regulators and multilateral organizations are expected to spur growth to help IBF to realize its true potential.

IBF in 2017

The year 2017 has proven to be a humdrum year for IBF, with no significant developments on a global level and in individual countries. GIFR 2018 will summaries some of the events, institutions and phenomena that assumed some sort of importance in 2017, and may have implications for future development of the industry.

Investment Account Platform

Investment Account Platform (IAP) is backed by Islamic banking institutions in Malaysia via the offering of Investment Account (IA) to the investors. Through this platform, Islamic banking institutions facilitate matching of investments with the identified ventures or projects that are in need of funding.

Following is an excerpt from a speech made by Dr. Zeti Akhtar Aziz, former Governor of Bank Negara Malaysia, which should explain the significance of IAP.

IAP is a centralized multi-bank platform that is likely to have significant implications on the role of financial intermediation in the Islamic financial system. This platform is more than just a new and innovative medium for Shari’a-compliant investments and fund-raising initiatives. It signifies a fundamental shift towards providing solutions that addresses the prevailing gap in the current risk-transfer financial regime to one that now allows for financial institutions to include a wider range of investment intermediation activities that emphasises risk-sharing and thus facilitate a stronger linkage of finance and the real economy.

Islamic finance in Malaysia has journeyed through different phases of development and has now evolved into a complete Islamic financial ecosystem that operates alongside the conventional financial system. Underpinning its growth has been the infrastructure and institutional development, product development that is reinforced by increased competition, and supported by a robust Shari’a, legal and regulatory framework. Its development has also been strongly anchored by the investment in human capital development. The industry has now not only achieved a market share beyond the target of 20 percent by the year 2010 as was envisioned in the Financial Sector Masterplan, but it has also met the increasing and differentiated demands of the economy through the range of financial product offerings in Islamic banking, takaful and Islamic capital market segments.

The initiatives taken to develop the Islamic financial system has aimed to build a comprehensive financial sector that operates at the highest efficiency and with an outreach that would extend beyond domestic and regional markets and thus facilitate greater cross border economic linkages. In advancing to the next level of growth and development, the Islamic Financial Services Act 2013 (IFSA) now provides the industry with the foundation to transition into its next stage of development. The Act takes into account the specificities of Islamic finance while ensuring a robust governance of an end-to-end Shari’a-compliant regulatory framework. It also provides an enabling environment for Islamic banks to diversify their business through the offering of investment accounts as an alternative means of raising funds from the public. With this, Islamic banks are allowed to pursue their role as investment intermediaries in which the alternative modes of risk-sharing contracts can be applied for the investment account.

This new categorization of deposits under the new Act has now been fully observed since mid-2015 with the effective reclassification of deposits to either being Islamic deposits or investment accounts. Following this exercise, the proportion of investment accounts to total funding for Islamic banks has increased from 7 percent in August to 10 percent as at December 2015, indicating a positive response towards this new product offering. This platform for the investment account is an evolutionary breakthrough that is uniquely designed for and driven by the industry. It will become a means by which both investors and entrepreneurs can experience and benefit from the new risk-rewards concepts embedded in the investment account. As an internet-based investment platform, the IAP provides convenience and facilitates greater access thus allowing for the efficient channelling of funds from investors to viable economic ventures and business activities.

Its robust risk management infrastructure, with a high degree of transparency and disclosure, differentiates the IAP from other technology-based fund-raising platforms. Islamic banks in performing their intermediation role in the operationalization of the investment accounts that are being offered on this platform, would rigorously undertake the credit assessment and screening of the listed ventures. The IAP would also require ratings on the listed ventures by rating agencies reinforced by the requirement for such ventures to comply to the disclosure standards thus enabling investors to make informed decisions. Integral to the platform is a mechanism for regular monitoring of the progress of the ventures, thus allowing for assessments to be undertaken by the sponsoring banks of any emerging risks associated with the ventures.

The value proposition and benefits of the IAP are multi-fold. It has the potential to spur the generation of new economic strengths through the promotion of entrepreneurship and job creation while also promoting greater financial inclusion and thus enhanced prospects for balanced growth. The IAP enables investors to directly finance a broad range of economic activity of their choice, therefore diversifying their investment portfolio with exposures to various types of projects and industries that yield potential returns that are based on the performance of the underlying chosen ventures. For businesses, the IAP provides a new source of funding for activities, with more competitive financing terms in a range of financing structures. Ventures and entities of varying types, size and industries, including SMEs, listed firms and multinational companies can raise funds on this platform. Given its greater visibility, the IAP will also provide access to a broader range of individuals and institutional investors.

For Islamic banks, the IAP creates a differentiated product that presents a new source of income and funding profile. There is also the potential for institutions with specific mandates including Government agencies to strategically collaborate with the IAP and Islamic banks to form public-private partnerships to facilitate the efficient channeling of grants or funding and to facilitate financing opportunities for identified strategic ventures.

The role of the IAP that is launched today is envisaged to transcend beyond our domestic borders to become an effective channel to further enhance financial interlink ages in the regional and global economy. It can also be enhanced to become a multi-currency investment platform to provide a marketplace for local and international investors to invest in real economic activity and projects denominated in various currencies and financed by Islamic banking institutions from different jurisdictions. This will be a first-of-its-kind shared global platform for Islamic finance. In facilitating cross-border transactions, the IAP will also contribute towards drawing new foreign investors while also allowing for participation in the financing of projects outside the country.

The IAP, together with the existing components of financial intermediation will form a more complete, and yet mutually complementary financial ecosystem. To ensure its success, there has to be greater awareness and understanding on the key features of the IAP and its embedded mechanisms by all the stakeholders. Of importance is for Islamic banks, investors and entrepreneurs to have a clear understanding on the risk and return relationships that are embedded in the variations of Shari’a contracts used in such investment account products. Expectations need to be aligned with the various approaches adopted to managing these relationships according to the contractual and operational requirements.

It is also paramount for Islamic banks to uphold the best practices in the conduct of discharging their fiduciary duties and in performing its administration. Of importance is the required due diligence, performance monitoring, suitability assessment and investment management. This would ensure that the IAP is always a trusted medium of investment that is transparent and competitive in providing a seamless experience for investors. This would address the concerns of investors on the risks associated with the asymmetry of information. Such features would contribute towards strengthening the ability of the IAP to attract a wider range of investors, therefore enabling the platform to cater for different types of risk profiles of the different ventures.

This shared infrastructure for advancing the delivery of the investment account product offerings represents an important platform to take this proposition forward. I wish to congratulate the six financial institutions that include four Islamic banks and two development financial institutions on their collective effort to initiate this platform. I understand there is interest from other Islamic banks to take part in this platform. This platform will have the potential to create a more extensive network of sponsoring banks to meet the more diversified demands of investors and ventures. This would further enhance the potential for the value proposition of the IAP as a Shari’a-compliant investment vehicle and a fund raising avenue that would bring benefits to the economy.

Active Involvement of Habib Bank AG Zurich in IBF

In this doom and gloom, there are some interesting developments unfolding. The story of Habib Bank AG Zurich is an interesting one. It is in the process of developing its Islamic banking brand Sirat, with a multi-jurisdictional approach. It has already established Islamic financial businesses in Pakistan and the UAE, and is in the process of launching its Islamic franchises in the UK and South Africa.

Increasing Significance of Islamic FinTech

Islamic FinTech is in vogue. There is not even a single conference, seminar or symposium in IBF where FinTech is not being discussed. With the growing emphasis on FinTech, there is now a renewed interest in Blockchain technologies and cryptocurrencies.

Emergence of Islamic Crowdfunding

Islamic crowdfunding is another opportunity that arose out of the rise of FinTech, but this opportunity is fast moving into oblivion, as Islamic financial players have not shown any considerable interest in it. ETHIS Crowdfunding is one development worth mentioning here. Despite efforts by the founders, IBF has so far not responded to this opportunity that have potential to create an ecosystem based on Islamic values.

Islamic crowdfunding may effectively be used to empower the masses to create products conducive with Islamic lifestyle that in turn is a basic ingredient for community development.

Islamic Reporting Initiative

Another interesting phenomenon that is fast attracting IBF is Islamic Reporting Initiative (IRI), which received recognition at the Global Islamic Finance Awards 2017 held in Astana, the capital city of Kazakhstan. It is developing a global reporting standard for sustainability and corporate social responsibility based on Islamic values.

Future Forecast

Given the continuing slowdown in the industry, we must revise future estimates of the size of the industry. If the trend continues, then one should expect the industry to reach the global size of US$2.987 trillion by 2020 (based on the current growth rate of 6.02%) or US$3.655 trillion if the industry somehow manages to grow by 14.56% (CAGR for 2007-17), which admittedly is highly unlikely. GIFR 2018 takes the official view that the global Islamic financial services industry will be merely US$3 trillion by 2020, which is just three years from now on.