Shari’a compliance is the core and essence of an Islamic financial institution (IFI). It enhances the integrity and continuity of IFIs while ensuring the legitimacy of Islamic financial products and services. This organizational goal is primarily achieved by having in placed a sound system of Shari’a governance that implements, monitors and reports an IFI’s compliance with Shari’a principles and rules. Shari’a auditing is an indispensable and independent organ of Shari’a governance, which ensures that the system of internal controls placed by management for Shari’a compliance is adequate and effective. However, Shari’a audit activity is prone to the influence of cognitive biases that adversely impact the judgment of Shari’a auditors. This chapter highlights common traps in Shari’a auditing along with effective antidotes.

Concept of Audit in Financial Industry

Audit is defined as a form of assurance in which a professional expresses conclusion with respect to a specific subject matter for the purpose of enhancing the confidence of intended stakeholders. Audit of financial statements encapsulates examining an entity’s financial statements and expressing an opinion whether the same provides a “true and fair view”. True and fair view succinct that the entity’s financial statements are not materially misstated and are unbiasedly represented. Principally, it is the responsibility of the management and those charged with governance to prepare financial statements that are free from fraud and error. In contrast, the auditor gathers sufficient and appropriate evidences to draw an independent

conclusion, which provides “reasonable assurance” that the financial statements are free from material misstatements. Reasonable assurance refer to the Shari’a auditor having obtained sufficient appropriate evidence to conclude that the subject matter conforms in all material respects. Audit is further classified into the following two broad categories:

a. External Audit: it is conducted by external auditors who are appointed by shareholders of an entity. External auditors are responsible to provide opinion on the true and fair view of the entity’s financial statements.

b. Internal Audit: it is defined by the Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) as an independent and objective assurance and a consulting activity designed to add value and improve an organization’s operations. Unlike external auditors, internal auditors are normally employees of the entity.

Why Shari’a Audit?

The traditional audit is greatly influenced by the capitalist worldview, which principally emphasizes on ensuring the interest of stakeholders only. For this reason, the international audit standards do not cover the religious aspects of financial affairs (Yaacob, 2012). Comparatively, the scope of auditing in Islamic framework is more dynamic as it stems from the concept of al-hisbah. According to Imam al-Ghazali, al-hisbah refers to a ‘comprehensive expression’ that invites one to do good and abstain from misdeeds (Ibrahim, 2015). Therefore, the scope of Shari’a auditing is not limited to the attestation of fair representation of financial aspects of an organisation, but to ensure that Shari’a controls are conceptually sound and effective in ensuring Islamic values and Shari’a principles of financial transactions (Lahsasna, 2016).

In the context of Islamic finance, Shari’a auditing can be defined as a form of independent assurance engagement, which provides “reasonable assurance” regarding an IFI’s compliance with Shari’a rules and principles as prescribed by the Shari’a board, central bank and other regulatory and standard-setting bodies. Its significance is derived from the fact that compliance with Shari’a rules and principles is the raison d’être of IFIs. Based on audit sample, Shari’a auditors detect and report any Shari’a anomalies and exceptions that betide during a specified time period (audit period) as a result of inadequate and/or ineffective controls, to those charged with governance. Moreover, the Shari’a board prescribes appropriate corrective actions against Shari’a audit observations.

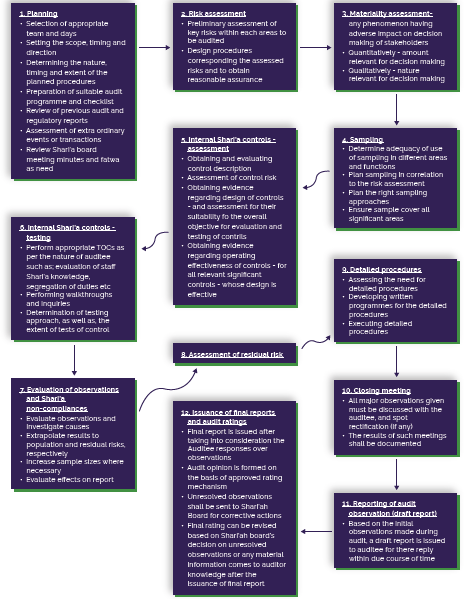

According to AAOIFI Exposure Draft (G1/2018) of Internal Shari’a Audit, the overall Shari’a audit exercise is illustrated in Figure 1.

SHARI’A AUDIT EXERCISE

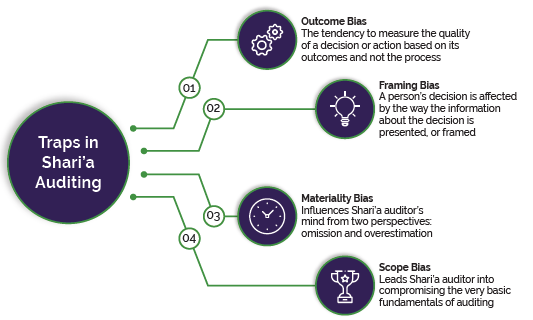

Psychological Traps

Psychologists have identified a series of manipulative flaws hardwired into the human thinking process known as cognitive biases. Cognitive biases are systematic patterns of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment and are often studied in psychology and behavioural economics (Hammond, Keeney, & Raiffa, 1998; Plous, 1993). This section highlights few traps that can potentially inf luence a Shari’a auditor’s mind, namely: (1) framing bias, (2) materiality bias, (3) outcome bias, and (4) scope bias.

1. Framing Bias

In audit walkthroughs, Shari’a auditor assesses the effectiveness and adequacy of internal Shari’a controls regarding adherence to Shari’a guidelines. During this exercise, he starts from the initiation of a transaction and walks it to the end. While doing so, the auditee explains the process flow of the procedures according to which a particular transaction is executed. It is also known in business management science as “framing the problem”. In Shari’a auditing, framing creates a mental border that encloses a particular aspect of a financial product or service to outline the key elements of it for in depth assessment. A mental frame enables Shari’a auditor to navigate the complex nature of a financial product, so that he can avoid examining the wrong aspects or evaluating the right task in a wrong way.

Shari’a auditors with Shari’a background, typically rely on information presented to them by the management of an IFI as they normally do not possess practical exposure to directly analyze complicated product or transaction. Therefore, the way a product is presented to them by the management actually shapes potential Shari’a considerations of Shari’a auditors (of course with some exceptional Shari’a minds that have nurtured with time, a phenomenal comprehension of financial markets).

A substantial amount of studies found that “framing” significantly impacts outcome of a decision. The framing effect is an example of cognitive bias, in which people react to a particular choice in different ways depending on how it is presented; e.g. as a loss or a gain, positive or negative (Paese, Bieser, & Tubbs, 1993; Snieder & Larner, 2009). Similarly, there are evidences suggesting that framing influences Shari’a judgment in Islamic finance industry depending on the manner in which a financial matter is presented (Agha, 2018).

A recent example of framing trap involves a commodity murabaha broking firm in the UAE. Following an investigation, the Dubai Financial Services Authority (DFSA) discovered that two-commodity brokers, David Barnett and Christopher Steer, facilitated a large number of murabaha transactions between 1st January 2014 and 31st December 2015 through the re-use of metal commodity titles previously purchased by the firm that were no longer valid, as the firm had ceased to purchase required titles to metal commodities. As a result, the DFSA imposed restrictions on David Barnett and Christopher Steer (Dubai Financial Services Authority, 2019).

From Shari’a audit standpoint, it was the responsibility of the Shari’a Audit team to examine the information presented to them by the auditee in order to assess whether the murabaha transactions were backed by actual assets, instead of relying on the frame presented to them by the auditee. To avoid such incidences, Shari’a auditor shouldn’t take for granted the initial frame formulated by the auditee. Rather, he should be cynic in his approach with thoroughness and an attitude of professional skepticism. In order to verify the accuracy of information presented before him, Shari’a auditor may obtain an ‘external confirmation’ by other legitimate and independent sources.

2. Outcome Bias

As a common phenomenon, people tend to measure the quality of a decision or action based on its outcomes and not the process. For example, they prefer a surgeon who has a high success rate instead of focusing on his skills and qualifications. Similarly, people judge hiring decisions not on the basis of whether the decision was made thoughtfully or fairly but on whether the new employee performs well (Gino, 2016). This tendency is known in psychology as the outcome bias (Gino, Moore, & Bazerman, 2009). It is a cognitive bias that misleads the brain in believing that similarity in the outcomes is result of similarity in the processes.

In Shari’a auditing, there have been instances where due to superficial knowledge of murabaha variants, auditors coming from purely accounting and finance background fall prey to outcome bias. For example, in one instance, a Shari’a auditor recommended the income of a murabaha transactions be channeled into a charity account, classifying the transaction as a ‘buy back’ based on the fact that the process flow stated the transaction as an ‘Advanced Payment Murabaha’ whereas the invoices were generated on a date falling after the date of disbursement.

The outcome bias misled the auditors into believing that similarity in the outcomes (receipt of invoices after declaration date) is the result of similarity in the processes (a buy back transaction). Fact of the matter is that the resemblance was a mere coincidence since the supplier of the murabaha commodity could not generate invoices on the due date owing to upgradation of its ERP system. It should be taken into consideration that the resemblance between the means and the end of two different financial products or services might be a mere coincidence, which does not necessarily lead to a comparable Shari’a ruling. In Islamic commercial law; instead of evaluating the outcome, validity of a contract is measured by ensuring the relevant governing Shari’a principles.

3. Materiality Bias

Materiality is a fundamental concept in auditing. It is usually assessed during the planning stage of an audit. However, the initial materiality assessments may be revisited according to the circumstances as the auditor proceeds with the audit activity. The International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (2017) states that misstatements, including omissions, are considered to be material if individually or in aggregate, they could reasonably be expected to influence the economic decisions of users taken on the basis of the financial statements. As a general rule, a threshold i.e. 5% of net income is considered immaterial during the formation of audit opinion. As a simple example, an expenditure of ten cents is generally immaterial from auditing perspective. If it was omitted or recorded incorrectly, no practical difference would result, even for a very small business. Thresholds based on other benchmarks, for example a certain percentage of total revenue or owner’s equity, may also be employed by an auditor.

However, in the context of Shari’a auditing, testing compliance with Shari’a rules and principles gives an entire new facet to materiality considerations. Accustomed with conventional auditing techniques hereditary into their subconscious mind, Shari’a auditors often fail to classify and assign proper weightage to audit observations. This bias influences Shari’a auditor’s mind from two perspectives:

• Omissions: excluding critical information from Shari’a audit report that have a material impact from Shari’a perspective such as non-reporting of Shari’a non-compliant event resulting in negligible charity amount or non-reporting of an erred calculation during profit distribution that results in understating the amount of profit.

• Overestimation: In some instances, Shari’a auditor overemphasizes on immaterial Shari’a non-compliances. It has been witnessed on scores of occasions that auditor gives gargantuan weightage to issues that are mostly operational in nature. As a consequence of “savior-of-Shari’a” demeanor, the auditor muddles the difference between a ‘violation of Shari’a rule’ and a ‘Shari’a control violation’ (which may not be an infringement of Shari’a rules in itself). This “every-observation-is-material” attitude was witnessed when the Shari’a audit rating of a business unit was downgraded because the unit manager could not provide documentary evidence regarding the dispatch of a few unit sale receipts at customer’s designated postal address (upon sale of bank’s musharaka share) in diminishing musharaka transactions.

Consequently, such hyperbole driven by materiality bias besmirch the reputation of Shari’a auditing as it paves way for management to believe that Shari’a auditors are playing the “religion” card with an aura of egotism. It also undermines the importance of Shari’a compliance because the whole focus of business units is shifted towards completion of mere paperwork and compliance with operational matters that they feel would please the Shari’a auditor.

From a Shari’a perspective, the financial impact of Shari’a non-compliance risk must be reported in the audit report no matter how insignificant its financial impact might be. This is due to the fact that violation of a Shari’a principle is not measured based on the materiality of its financial outcome, rather it depends on the nature of the violation and its severity. Therefore, in Shari’a auditing, materiality means not just a quantified amount, but the effect that amount will have in various contexts from earning to distribution.

4. Scope Bias

An efficient audit process relies on both the auditor and auditee being clear on what the audit covers, that is, its scope. The scope covers audit period, auditable areas and the applicable laws, rules and regulations. A predetermined scope creates an atmosphere of cooperation and trust that makes an audit a value addition to the organization. It establishes how efficiently an audit is performed by providing an independent and objective opinion. It also assists the auditee to prepare for the audit, gather documents and records, and ensure ahead of time that the right people are available during audit.

A shallow scope or bypassing the scope of audit not only creates a mismatch between expectations of the parties, but also impairs the objectivity of the audit exercise. This happens when an auditor fails to understand his or her “independency” and exerts authoritative behaviour. The scope bias misleads the auditor’s judgment while assessing the object’s attributes. There have been cases where Shari’a auditors question the legality of Shari’a board resolutions and fatwa. Instead of making recommendations, Shari’a auditors provide Shari’a opinion, which is the responsibility of the Shari’a board.

Moreover, this cognitive bias sometimes leads Shari’a auditor into compromising the very basic fundamentals of auditing such as risk assessment, sampling and level of assurance. The auditor starts developing a habit of assuming that, by virtue of his critical role, he is responsible for detecting each fraud and error and hence, the level of assurance provided by Shari’a auditor must be an absolute assurance (instead of reasonable Shari’a assurance). In some cases, it is witnessed that a significant proportion of auditor’s time is frittered away in checking the completeness of required fields in transactional documents. He spends more energy in examining documents while the accounting aspects and reflection in core banking system is mostly ignored. Consequently, the audit report speaks feebly of major control loopholes in income recognition and distribution process.

In the same vein, it is sometimes observed that Shari’a board influences outcome of the audit report such as assigning a desired audit rating. To curtail the risk of scope bias from both sides, auditor should have a lucid understanding of his or her job description. As per AAOIFI guidelines, the scope of Shari’a auditing is to provide a “reasonable assurance” regarding an IFI’s compliance with Shari’a rules and principles as prescribed by the Shari’a board, central bank and other regulatory and standard-setting bodies.

From a juristic perspective, the difference between the scope of Shari’a board and Shari’a audit team can be clearly seen in tahqiqul manat al-khas and tahqiqul maat al-am— terms used in Islamic jurisprudence. Tahqiqul manat al-am is the scope of a Shari’a auditor and it refers to the application of a common Shari’a principle or ruling into a well-known phenomenon without looking to its specification (Al-Shatibi, 1997). For example, Shari’a requires that both counter values in a sale transaction must be clearly defined to avoid any ambiguity that may result in dispute. To assess compliance to this principle, Shari’a auditor checks offer and acceptance letter and other relevant documents to verify whether quality and quantity of the asset and price are clearly communicated.

On the other hand, tahqiqul manat al-khas is the responsibility of the Shari’a board. It is defined as an application of Shari’a principles into a certain case with due consideration to its specification. For instance, an Islamic legal maxim states that any loan that drives a benefit (for the creditor) is riba (interest). During the audit of current deposits—broadly classified as loan to the bank by account holders— if Shari’a auditor finds that the bank gives certain benefits to the account holders such as free chequebook, online banking and discount on debit card etc.; instead of reporting it as riba, he shall refer it to the Shari’a board who will decide whether it is riba or permissible practice after examining the customary practices and specific nature of this phenomenon. In other words, Shari’a auditors cannot question the legality of Shari’a decisions made by Shari’a board nor can they prescribe Shari’a rulings by themselves. Their job is to examine the application of a pre-described Shari’a ruling into auditable cases.

Nevertheless, the auditors can question the accuracy of the “description” (tasawur al-mas’alah) of the case presented to the Shari’a board by management to obtain a Shari’a ruling. For instance, Shari’a board was informed about a transaction that the bank’s ownership of the asset is represented by a specific document and hence, the board ruled that the bank can sell the asset to the customer after possession of the document. However, during audit, auditor observed that the said document does not represent the bank’s ownership for certain reasons. In this case, Shari’a auditor should inform the board that the Shari’a ruling should be revisited.

Conclusion

Psychologists have identified a series of manipulative flaws hardwired into human neural pathway, which we often fail to recognize during decision-making. Making a judgment during Shari’a auditing is apparently not an exception. By analyzing the above facts, it can be concluded that these traps together point towards two key findings.

First, a biased audit observation might be the result of partial understanding of Shari’a auditor and his shallow judgment. An erred reporting will not only undermine the role and reputation of Shari’a audit but might also trigger reputational risk for the auditee. Second, most of these traps are correlated. Falling into one trap often leads to become prey of other traps as well. Avoiding these traps largely depends on proper audit qualification, and the expertise developed during audit career. Furthermore, due to the different nature of auditee’s business, auditors are always susceptible to these traps during an audit exercise despite having a successful track record. Therefore, it is important to occasionally step back and discuss mistakes that can prevent or derail success.