Undoubtedly, Fintech growth is relentless but understanding the future of Fintech requires a re-engineering of how financial institutions operate and are regulated. E-commerce businesses like Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google prove that smart data management can create a customer understanding like no other. Across retail, wholesale, and capital markets; banks are ardently aware that the digital-first model based on high-performance data analysis will create a massive advantage. An effective and conducive regulatory system is key to the success of jurisdictions in order to remain competitive in the global market with the use of Fintech. The chapter discusses the evolution, challenges and recommendations for the Islamic finance regulators in the management and regulation of new tech.

Digital Transformation in the Financial Industry

Digital transformation is imperative for the financial services industry to remain competitive and achieve longevity in the market. The continued existence of financial institutions is connected with the implementation of innovation, and in embracing digital transformation to radically improve efficiency and performance within the organisation. Digital transformation and new technology adoption have changed the way of doing business and these new ways have resulted in reshaping the existing models of businesses and the creation of new innovative ones. Unlike the digitization of developed country wholesale and institutional markets, digital financial services in most developing countries have generally developed independently of the efforts of financial regulators and usually led by mobile telecommunications companies (Runde, 2015). In many jurisdictions, market regulators only started to address potential risks to consumers and financial stability once mobile payments had already become mainstream in the domestic financial system.

The digital transformation shift has also changed the expectations and wants of the customers. Today, customers want banking (and other financial services) from anywhere they are and at any time, regardless of whether they are in the office, or at home in the evenings, or at a beach or in a park at the weekend. This digital behaviour of customers has set a new bar for the services industries, and the industry is trying to cope with the needs of the digital mindset by using Omni channels and advanced technologies. Having better insights into how customers behave in their preferred buying channels also allows businesses to identify the right moment to intervene and develop a comprehensive strategy that works holistically across channels such as search, video, social, and display (Mohamed & Ali, 2019). Chatbots and robo-advisory solutions are the modes in which Fintech has become relevant to every customer without the need for an array of disparate customized solutions. Built into messaging apps, Chatbots come as close to the customer as possible by being a personal assistant in any enterprise. They provide a pertinent answer and allow the clients to complete a purchase immediately with the help that is provided.

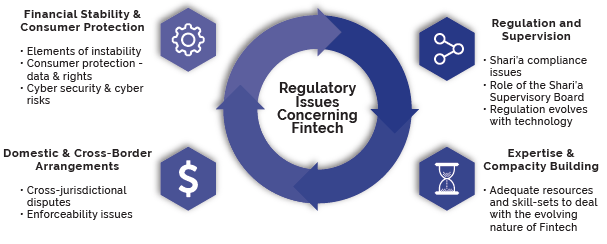

Regulatory Issues Concerning Fintech

Fintech is accelerating at a scale that quickly presents apparent economic benefits to the financial system and society at large, but it may also have potential risks from unintended consequences. Some of these concerns, though not exhaustive, include the followings:

• Regulation and Supervision

By and large, regulators are aware that Fintech has the potential to deliver immense economic benefits, by lowering the cost of operations and enhancing competition; and societal benefits, by boosting financial inclusion and delivering more convenient financial services. However, risk and failure are an integral part of innovation in Fintech solutions. Therefore, it is critical for regulators to ensure that safeguards are in place to manage risks including institution-specific micro-financial risks and system-wide macro-financial risks. Providing parameters and regulatory clarity through a framework (for Fintech business models) is essential for Fintech’s mass adoption in order to ensure the financial stability of the system. Regulatory sandboxes are only one of the approaches to manage Fintech and may not fit circumstances in different situations and jurisdictions. Market supervisors will have to ensure that financial institutions or firms have robust governance frameworks and such surveillance could be complemented by data-driven supervision.

Other risks include those associated with the usage of digital currency, which the public may not be aware of. Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs) is a new method of raising capital through decentralized means, which has the potential to side-step rigorous regulatory requirements for fund-raising established by authorities. In addition, there is serious trepidation on the risk of money laundering and financing of terrorism, termed as AML/CFT, which requires financial institutions including banks to have adequate measures to counter the risk of AML/CFT.

Another significant risk management concern is the operational risk that reflects cyber-security, fraud and theft, data privacy and legal issues. Similar to the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), the Islamic finance standard-setting body known as Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB) prescribes a capital regime for operational risk, which does not really address risk-related operational issues. While regulatory instruments such as BCBS/ IFSB capital requirements can create incentives to address certain operational risks, such as business continuity; capital is not sufficient to restore operations if a financial institution suffers a cyber-attack. Cyber-security and Critical Information Technology Infrastructure (CITI) resilience have to be given considerable attention by market supervisors of all sectors, especially the banking and financial industry.

Specific to Islamic finance, the innovative solutions for Islamic financial services should be consistent with Shari’a rules and principles, and it takes adequate knowledge in the relevant economic, financial and technical areas including artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain, Internet of Things (IoTs), and machine learning. This is a huge concern in the role of the Shari’a Supervisory Board (SSB) in overseeing product innovation at the institutional level, which impacts Shari’a compliance issues for enhanced supervision. The assessment of Shari’a compliance too should include the procedural processes from creation to the result of any crypto-assets and its mechanisms. In this respect, CIBAFI has recently suggested (in its comments submitted to the BCBS’s consultative document) that Islamic banks will need to consider how they can safeguard the end-to-end transactions according to the Shari’a, including the rights and ownership at each stage. While other bodies, such as the IFSB, have also highlighted the challenges that Fintech innovations cause.

Thorough guidance covering all the modalities of the Fintech issues for Islamic finance is unrealistic, and such expectations need to be reframed. The appropriate regulations will have to be created (or adjusted) as the technology itself evolves. The assumption that regulations, once crafted will remain in place and unchanged for significant periods of time has been overturned in today’s environment. As new business models and services emerge, such as sharing services (e.g. Airbnb and Grab) and ICOs; government agencies are challenged with creating or modifying regulations, enforcing them, and communicating them to the stakeholders; while working within legacy frameworks and striving to foster innovation.

• Financial Stability and Consumer Protection

Market supervisors will need to ensure that financial institutions including banks have in place robust plans for scenarios that could threaten their own stability or the larger macroeconomic stability. For instance, in Robo-advisory services, which rely on algorithms and portfolio management to analyze investors’ data and automatically recommend investment portfolios, advisory information needs to be within approved products and companies offering such services need to be compelled to disclose more information when required. Similarly, third-party service providers or vendors to financial institutions are becoming more common and critical, especially in the areas of cloud computing and data services. Such third-party technology providers may need to be regulated in order to manage related operational risks, which may impact financial stability indirectly.

Under financial stability, consumer protection including personal data protection is one of the highly focused areas. The danger of cyber-attacks and hacking, as well as the need to protect sensitive consumer and corporate financial data, is very real. Unquestionably, a number of recent incidents involving fraud, theft, and breaches of personally identifiable information, have raised many issues including data privacy, ownership and administration, and legal liability. In order to avoid undesirable situations, much work needs to be done on boosting cyber security and alleviating cyber risks.

• Domestic and Cross-Border Arrangements

Both domestic and cross-border transactions are important for supervisors. Domestically for Fintech developments, there has to be coordination among the supervisory agencies regulating financial institutions. A common approach and strategy need to be in place to address Fintech issues at the national and international levels. Hence, regional cooperation will be integral in regulating Fintech that scale beyond borders. Furthermore, innovations in cross-border lending, trading and payment transactions including via smart contracts; raise questions about cross-jurisdictional disputes and enforceability issues.

• Expertise and Capacity Building

Talent and the right expertise are one of the areas that require attention and need to be addressed moving forward. Though traditionally for supervisors, this has not been a key concern, there are serious challenges for building staff capacity in new areas of the required technical expertise. As traditional roles within some areas of the Islamic banks become automated, forward-thinking planning for capacity building and innovation-related expertise has to be part of the overall strategy in order to provide proper market supervision. Financial market and conduct supervisors should feature greater emphasis on ensuring that they have adequate resources and skill-sets to deal with the evolving nature of Fintech. Additionally, authorities should ensure that regulators and financial institutions work collaboratively and pre-emptively towards the development of the next generation of IT infrastructure and cloud-based systems to build transparency and accountability.

RegTech – Digital Reporting and Compliance

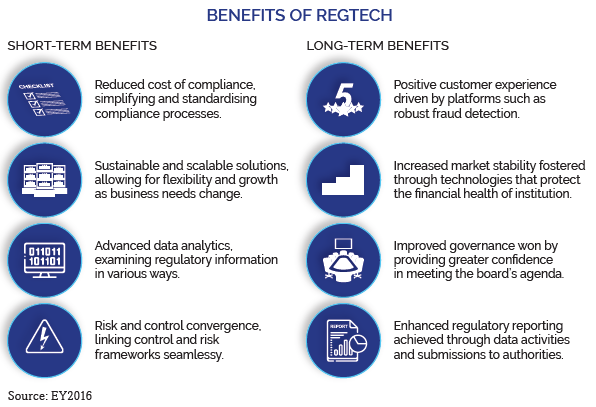

Around the world, regulators are facing the challenges of the rapid emergence of new Fintech technologies and non-traditional market entrants, all at extraordinary speed. Authorities are faced with the task to develop regulatory approaches that do not hamper development and innovation while still limiting risks to consumers and financial stability. RegTech is largely seen as a category that focuses on technologies that may facilitate the delivery of regulatory requirements more efficiently and effectively than existing capabilities. However, RegTech can be viewed more than just an effective tool but rather a pivotal change leading to a paradigm shift in regulation as RegTech holistically represents the next logical evolution of financial services regulation and should develop into a foundational base underpinning the entire financial services sector (Arner et al., 2016).

The application of technology to monitoring and compliance offers massive cost savings to established financial companies and potentially massive opportunities to emerging Fintech start-ups, IT and advisory firms (Shedden & Malna, 2016). From a regulator’s perspective, RegTech will enable the prospect of continuous monitoring that would improve efficiency by both liberating excess regulatory capital, decreasing the time it takes to investigate a firm, fostering competition and upholding their directives for financial stability (both macro and micro) as well as market integrity (Gutierrez, 2014).

• Cybersecurity

While regulators regulate prescribed market behaviours, there is a need for an independent agency that enforces and acts when there is a security breach in the Critical Information Technology Infrastructure (CITI) within corporations and government information systems. Hence, a National Cybersecurity Agency (NCsA) is recommended to establish a legal framework for the oversight and maintenance of national cybersecurity in the country. The agency will also be responsible to develop and enforce cyber-secure framework to be used in conjunction with any existing Systems Development Lifecycle (SDLC) methodologies adopted by organizations, as well as complementing government policies, standards, guidelines and directives.

While most organizations acknowledge that security is an important consideration in developing computer systems, costs and business performance often take precedence over security. Even though awareness has been elevated on security issues, most organizations focus on applying security only at the commissioning stage of the system development and try to force-fit security into the final design, thus resulting in the ineffective application of security.

An effective way to protect computer systems against cyber threats is to integrate security into every step of the SDLC; from initiation to development, deployment and eventual disposal of the system. Control Gates or decision points are specific milestones where the security implementations are evaluated. They specify to the corporation that security considerations are addressed, adequate security controls are built in, and identified risks are clearly understood before the system development advances to the next lifecycle phase. The agile approach can be adapted to continuously update and improve standards. Security planning is to be conducted as part of integrating security in SDLC, and should include:

- Identifying and confirming key security roles in the system development project.

- Outlining key security milestones and activities for the system development

- Connecting the use of secure design, IT architecture and coding standards

- Warranting all key stakeholders having a shared understanding of the goals, implications, considerations and requirements of performing security.

These values integration is crucial in responding to potential security threats as it highlights to key stakeholders important areas of systems development progress, and that critical decisions made will have security implications.

In addition, a Bill or an Act can be enacted to:

1. Empower NCsA to Prevent and Respond to Cybersecurity Threats and Incidents

The Act can empower an authority (e.g. a national cybersecurity agency like NCsA) to investigate cybersecurity threats and incidents to determine their impact and prevent further harm or cybersecurity incidents from arising. The powers that may be exercised are adjusted to the severity of the cybersecurity threat or event and the appropriate measures required for a response. CITI sectors are banking and finance, emergency services, health (hospitals, etc.), transport (air, land and sea), information communications (media, etc.), power and water.

2. Create a Framework for Sharing Cybersecurity Information

The Act can also facilitate information sharing, which is critical as timely information helps the government and owners of computer systems to identify vulnerabilities and prevent cyber incidents more effectively. The Act can also provide a framework for NCsA to request information, and for the protection and sharing of private, restricted or sensitive information.

3. Launch a Licensing Framework for Cybersecurity Service Providers

NCsA can act to license different types of service providers, namely those involved in cyber-threat penetration testing, cyber-defence and managed security operations monitoring. These services are prioritized because providers of such services have access to sensitive information and hence have a significant impact on the overall security landscape. The licensing framework allows for a balance between security needs and the development of a vibrant cybersecurity ecosystem.

Institution-Specific Micro-Financial Risks

In order to protect computer systems against cyber threats it is important to integrate security into every step of the SDLC, which is called the Security-by-Design (SBD) approach. The SBD is an approach to software and hardware development that seeks to minimize systems vulnerabilities and reduce the attack surface through designing and building security in every phase of the SDLC. This includes incorporating security specifications in the design, continuous security evaluation at each phase and adherence to best practices. The values of integrating security into SDLC include:

- Early identification and mitigation of security vulnerabilities and misconfigurations of systems.

- Identification of shared security services and tools to reduce cost, while improving security posture through proven methods and techniques.

- Facilitation of informed key stakeholder decisions through comprehensive risk management in a timely manner.

- Documentation of important security decisions throughout the lifecycle of the system and ensuring that security was fully considered during all phases.

- Improved systems operability that would otherwise be hampered by isolated security of systems.

Specific to cyber security, SBD addresses the cyber protection considerations throughout a system’s lifecycle. This includes security design specifically for the identification, protection, detection, response and recovery capabilities to strengthen the cyber resiliency of the system.

• System-Wide Macro-Prudential Policy for Financial Stability

Macro-financial issues related to systemic importance are embedded in the FSB SIFI2 framework, which recommends that financial institutions, which are identified as systemically important, should have more intense supervisory oversight, higher loss absorbency as well as recovery and resolution plans. The majority of regulatory changes and clarifications have been made in the areas of payments, capital raising, and to a lesser extent investment management as many of these economic functions naturally fit within existing regulatory regimes. Only a few regulatory changes to include Fintech innovations in insurance and market support were mentioned (FSB, 2017).

International cooperation will be crucial given the commonalities and global dimension of many Fintech activities. There is potential for international bodies, like the IFSB, FSB, the GPFI and SSBs – such as the BCBS, IAIS, IOSCO and CPMI – to provide avenues for authorities to get together to share experiences on Fintech implications for financial markets. Increased cooperation will be particularly important to mitigate the risk of fragmentation or divergence in regulatory frameworks, which could impede the development and diffusion of beneficial innovations in financial services, and limit the effectiveness to promote financial stability.

Because innovations in financial services are developing fast, authorities may further wish to consider the following issues:

i. Cross-border Legal Considerations and Regulatory Arrangements

Cross-border cooperation and coordination among authorities are important to a well-functioning financial system. Financial innovations in cross-border lending, trading and payments, via tokenized systems, begs the question about the cross-jurisdictional compatibility of national legal frameworks. The legal validity and enforceability of smart contracts and other applications of DLT are in some cases uncertain and should be discussed in greater detail. In addition, in some cases, certain technological structures around DLT and smart contracts may not necessarily be designed to comply with the laws of all potential jurisdictions, thus affecting their scale on cross-border applications.

ii. Governance and Disclosure Frameworks Supporting Big Data Analytics

Applications of big data are becoming more prevalent as a basis for financial services across the full range of economic functions, including lending, investment and insurance. Big data analytics give rise to several ways for the financial services industry to achieve business advantages by mining and analyzing data. They include enhanced detection to identify exposure in real-time across a range of sophisticated financial instruments like derivatives. Predictive analysis of both internal and external data results in good, proactive management of a wide range of problems across industries with the ability to conduct extensive analytics rapidly and enhance risk identification and assessment. Similar to the use of algorithms in other domains, such as securities trading; the complexity and opacity of some big data analytics models makes it difficult for authorities to assess the robustness of the models or new unforeseen risks in market behaviour, and to determine whether market participants are fully in control over their systems.

iii. Studying Alternative Configurations of Digital Currencies

The repercussions of hybrid configurations of cryptocurrencies for national financial systems and the global monetary framework should be investigated. Digital currencies and alternative payment arrangements based on new technology are developing at different speeds across jurisdictions, along with a decline in the use of cash for transactions in some jurisdictions (FSB, 2017). On top of monitoring developments, relevant authorities should examine the potential implications of cryptocurrencies for monetary policy, financial stability and the global monetary system.

• Shari’a-Compliance

The main risk that Islamic financial institutions (IFIs) face which is unique to them is the Shari’a-compliance risk. In addition to managing the risks faced by conventional banks, such as credit, market, operational risks; IFIs also has to ensure that it complies to Shari’a rulings as this carries significant reputational risk to the institutions. Fintech products (including cryptocurrencies and tokens) and services need to be treated differently according to the fiqh understanding of the Shari’a as well as the regulatory authorities because of its nature and usage. Due to this, its treatment by the regulators as well as Islamic jurists will be in accordance to its nature and utilization — the way they are used as well as the way they were intended to be used — and this should be done first by effectively categorizing such products before fiqh rulings can be applied to them.

The assessment of Shari’a-compliance too should include the procedural processes from creation to the result of any digital crypto-assets and its mechanisms. For compliance and legitimacy, before launching a project of any digital crypto-assets, it should be scrutinized as per fiqh guidelines (from Shari’a committees). In the absence of those guidelines, clarification should be sought from Shari’a experts who have the relevant economic, financial and technical (blockchain and token experience) capability. Shari’a advisory scholars now need to be adept with the underlying technology, which drives digital Shari’a solutions to adequately assess Shari’a compliance. These Shari’a scholars also need to be well versed in conventional and Islamic economics and finance to make sound decisions and would require future scholars to be multidisciplinary, just like their iconic predecessors in the past golden age of Islam.

The RegTech Trajectory

Policymakers and watchdogs will confront rapidly transforming financial systems in the coming years. In building the necessary infrastructure to support their regulation, there will be increased use and reliance on RegTech. This will have to take place in close cooperation with all industry participants. The development of RegTech so far has primarily been driven by the financial services industry wishing to decrease costs, especially in light of the fact that regulatory fines and settlements have increased 45 fold (Kaminsky & Robu, 2016). The next stage is likely to be driven by regulators seeking to increase their supervisory capacity by automating compliance and regulatory surveillance.

• Cooperation and Mutual Learning

Interoperability, coordination and collaboration are the essential elements of any developed and successful ecosystem around the globe. This involves different governments, public and private sectors indigenously and outside the region. Public and private sectors can establish safe, secure, reliable and affordable open and shared platforms for digital payments, banking services and other financial alternatives by converging their offers via Omni-channels (offering the customers integrated and consistent financial platforms). These include regulatory supervision. The regulator can initiate market meetings, discussions and consultations, and also begin regulatory sandbox experiments. The main contribution of a sandbox from a regulator’s perspective may not be in the controlled experimental safe space, but instead in communicating regulator flexibility towards innovative enterprises, and the regulator’s desire to understand new technologies. For many regulators, their doors need to stay open to facilitate knowledge transfer in an era of rapid technological change.

• Updating the Regulatory Toolkit

So far, regulators have applied various tools from their regulatory toolkit from traditional approaches to regulating or decision not to regulate, to thoughtful testing through forbearance, special charters, or restricted licenses; and controlled and transparent experimentation through regulatory sandboxes or piloting. A growing number of regulators are beginning to experiment with novel approaches, seeking to unlock innovative potential by fostering innovation while minimizing risks, preserving consumer protection and ensuring market stability. This iterative process has gradually increased regulators’ sophistication in their understanding of Fintech innovations and business models.

• Improving Regulations and Responding to Market Evolution

Fintech growth has drawn the need for RegTech, the need to use technology, particularly in managing large data-sets and audit trails; in the context of regulation, monitoring, reporting, and compliance. Colleges, business schools and universities should also enhance training of next-generation of talent through updating their current curriculum by adding courses that focus on Fintech, Design Thinking, Coding and Product Development, Micro-Financial Risk Management and Macro-Prudential Supervision of the impacts and unintended consequences of Fintech, and of course, cyber security.

Conclusion

The main entities within the innovation ecosystem are the regulators, Islamic Fintech companies, IFIs, venture capitalists, government agencies, strategy and technology consultants, media and academia (Mohamed & Ali, 2019). These entities make up the demand and supply sides of the digital ecosystem. Every crucial component gives support to each other and strengthens each other for the attainment of common and collective objectives. Each stakeholder plays its role and uses its resource and capability to provide solutions. Regulators may provide innovation-friendly policies and an environment that gives incentives to Islamic Fintech platforms to test and refine their innovative ideas, and IFIs may provide financial services or access to their internal sources and financial expertise. Incubators and regulatory sandboxes allow for the trial of prototypes in a controlled environment, while the media and academia may provide insights into trends and conduct proof-of-concept research to determine viable solutions for the gap in the industry. Stakeholders must ensure their organizations can pivot with market shifts, even dropping or switching partnerships if the market turns. The ability to adapt to new conditions will be a driving factor in maintaining a prosperous and dynamic digital ecosystem, as technology and its use causes change and as market needs evolve.