Self-perception

The takaful and retakaful industry is no longer in its infancy – it has experienced the incorporation boom in the early years of the new century, the harsh and stormy conditions surrounding the prolonged global financial crisis, and markets characterized by falling prices and fierce competition. While the industry is gradually creating a discernible track record and perceptions are consolidating, new challenges are arising. New markets, particularly in the African continent are forming, regulations are being reviewed, and some shareholders are sooner or later likely to take stock of past years’ experience.

Similarly, when humans come of age and spread their wings, the challenge they have to face before facing all other challenges ahead is that of becoming aware of themselves: who are they, what are their potentialities, and what are their desires The self-image sets the foundations for further development and determines what they will become in the years to follow. Now, what is the self-image of takaful? Is it currently taking on a new form, and in what direction?

The term “takaful” has gained popularity only recently – apparently from Malaysia – referring to all forms of Shari’a-compliant insurance. Originally, and according to AAOIFI standards – and still in Sudan – the term “Islamic insurance” was used, while takaful related to Islamic life insurance only. The basic question driving both internal and public discussion is whether takaful is a form of Islamic insurance with major differences, whether is it simply insurance with Arabic terminology, or is it a completely different animal altogether. There is a broad group within the industry that sees takaful as something intrinsically different from conventional insurance – a replacement for it, not just an adaptation of insurance principles to Islamic precepts. The external view is in sharp contrast. What the public seems to notice first are the similarities to insurance, simply concluding that takaful is just “insurance with the basmalla on it.” It appears that a considerable number of potential buyers (and in any event, of course, the conventional competitors) are inclined to contend that takaful constitutes mere window-dressing or to challenge the company’s claim to be different, cleaner and better. There are surely new niches for shari’a-compliant risk-management institutions, but the industry is currently entering the same market segments and risks as those already occupied by conventional insurance.

- New momentum in the discussion on the nature of takaful

In the first few decades of its existence, the takaful set-up appeared quite stable and unquestioned. There was certain unease among most scholars and many practitioners regarding the application of the takaful-mudaraba model in Malaysia, which was considered “second best” to the takaful-wakala model, since the participation of the shareholders in overall surpluses, including underwriting surpluses, was considered a breach of the risk-sharing principle. However, there was a clear idea of how takaful operations should function once critical mass and some maturity, was achieved.

Today, with exponentially more takaful companies operational – many of them, as in Jordan, Kuwait or the Emirates, working on wakala basis – and with retakaful companies appearing on the scene with their specific needs and portfolio structures, the theoretical set-up has to some extent been put to the test and has also become subject to closer scrutiny by different bodies and global players with their expertise in different areas. GIFR 2012 chapter on takaful has already addressed many of the technical issues. Bank Negara has launched drafts and conducted discussions between industry players to define a concrete operational takaful framework, and AAOIFI and IFSB are also working on defining a framework. In addition, a new process of exchanging views between scholars and practitioners has begun at different levels. The most prominent of those meetings took place in June 2011 through the initiative of Munich Re’s Shari’a board. The Shari’a boards and leading practitioners of the three global players active in retakaful, namely Munich Re, Swiss Re, and Hanover Re, attended. The meeting ended with the setting of a number of principles including a resolution stating that the building of sub-pools that comprise only one client for the purpose of surplus redistribution (practised in particular in retakaful) was against the spirit of solidarity and risk sharing.

The risk-sharing principle is brought down to the accounting level: Who carries the risk?

In takaful theory, the risk is carried only by the contributions (which are legally considered to be donations or tabarru) paid into the participants’ fund. Temporary deficits can be covered by injections (in the legal form of an interest-free/benevolent loan or qard Hasan) and recovered from future income. Some scholars already prefer to call this loan “qard” only due to its apparent differences with the classical Islamic conceptualization of benevolent loans. Qard hasan, originally, were voluntary in their payment and obligatory in repayment. For qard, they are voluntary in their repayment. From the point of view of an insurance regulator, cover that can, but does not have to be given is detrimental to consumer protection and contradicts the principle of insurance. To provide legal material cover, the qard payment has to be obligatory and regulators expect or stipulate that. The Islamic Finance Service Board (IFSB), acknowledged2 that both the shareholders’ and the participants’ funds together must be taken as a guaranteed sum for solvency purposes. As for the re-payment of the qard, it cannot formally be considered obligatory since no one is personally liable for replenishing the participant’s fund. Expecting cover of past losses by future surpluses is what conventional insurers do as well. Thus, materially, the qard is not receivable. Parallel to efforts by the AAOIFI and IFSB to elaborate accounting rules for these items, Malaysian regulation proposed an impairment of the qard after a number of years, which in a way appears to be an attempt to maintain the legal term without the economic essence of a loan. Bank Negara has also addressed the problem of liability and risk capital, including approaches to assigning risk capital to the two funds.

These efforts are most helpful in creating not only a transparent regulatory and accounting basis. They also clarify the nature of the takaful proposition at least as far as its financial dimension is concerned. There are donations given against creating an entitlement (hiba bi-thawab) and there is a benevolent loan which is obligatory, commercially motivated and not exactly a loan either. The result is a financial value proposition to the participants that is hardly distinguishable from that of a conventional insurer. Nor is the mutual and cooperative character very apparent, either in participation in decision-making or in financial surpluses.

In search of a definition of the core characteristics: pooling

The resolution of the leading scholars at the aforementioned June 2011 meeting initiated the search for a more concrete definition of “pooling” (used more or less interchangeably with risk-sharing) as the practical implementation of the value of solidarity. In short, this definition requires that participants (in retakaful, these are the takaful operators) demonstrate their solidarity by giving away possible individually earned surplus – equivalent to conventional profit commission – to cover deficits produced by other takaful operators, including even their direct competitors. This definition has several strengths: firstly, it is based on a spiritual value, which is the basic distinguishing feature of takaful; secondly, it is financially measurable and, at times, implies a real material sacrifice that proves the solidarity value; thirdly, takaful operators have indeed been inclined to insist on the individual calculation of their treaties, which has been a decisive factor in streamlining most retakaful agreements towards a copy of conventional reinsurance treaties.

Following the resolution on this definition of pooling attempts at implementation commenced, in particular by the Malaysian Takaful Association which aims to create a common pool, at least for the Malaysian business. This would represent a sort of first step or compromise between the current practice and the ideal of a global pool.

The resolution, despite its strengths mentioned above, is in its current form not comprehensive enough to provide a basis for a different kind of retakaful. Nor does it as such provide additional technical value over and above the spiritual dimension. The arguments below seek to justify this stance, in particular regarding the first point, namely the comprehensiveness of the ruling.

Pricing Methodology

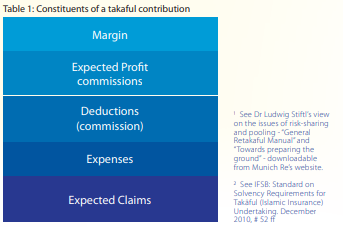

We confine ourselves here to retakaful, for which the ruling was made. Moreover, we exclude for the time being non-proportional business, where usually no surplus is available at all (yet another issue a more comprehensive ruling should deal with). A retakaful operator’s, as well as a reinsurer, main task in managing a pool, is underwriting. This means assessing the risks and the claims expected to emanate from them. The assessment should comprise both the frequency and the severity of the claims, as well as the volatility of their occurrence. The constituents of the total contribution derived by use of this assessment can be seen in Table 1.

With the introduction of what is often called “pooling of the surplus,”3 the expected surplus redistribution (“profit commission” in conventional terminology) becomes a function of the whole portfolio. This means that individual participants can no longer estimate their surplus redistribution because the information on the whole portfolio and its quality is in the hands of the retakaful operator. Nor can they exert influence on the retakaful operator’s choice of other takaful operators for the pool. At this point, game theory would come in, and we need to take opportunistic behaviour into account: firstly, because this is realistic and cautious; secondly, because takaful and retakaful operators are in themselves commercial ventures; and thirdly they have a duty to ensure that the funds they are responsible for are properly managed financially.

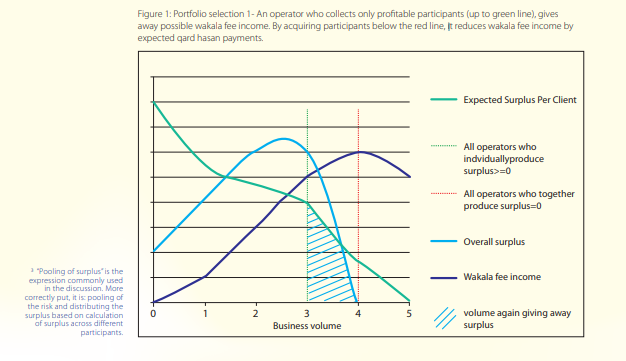

On the assumption of opportunistic behavior, the retakaful operator, whose wakala fee is dependent on the volume of business written, would optimize its portfolio by maximizing its volume until the expected surplus redistribution is zero. Starting the building of the fund with good (meaning adequately priced) risks that allow for an expected surplus, the retakaful operator would bring in less generously priced risks (or, which amounts to the same, attract business by granting contribution discounts) until deficits – and thus qard hasan from his shareholder fund – were to be expected (see Figure 1). In theory, he can achieve a good wakala fee income and also a positive margin by selecting adequately priced risks. However, operators adopting this strategy need selling propositions that help them retain the good risks in the face of attempts by the competition to take from them by price undercutting. Today’s reality, also seen in the conventional world, bears witness to both strategies, with the undercutting strategy being observed far more often.

Let us now look at the viewpoint of a – more or less – opportunistic participant (takaful operator). It cannot know who else is in the pool but can assume – or learn by observation – that an opportunistic retakaful operator would adopt a strategy of assembling a pool in order to bring the expected surplus redistribution to zero. It would consequently be rational for the takaful operator not to expect any surplus and, what is more, due professional caution requires it not to expect any, since there is insufficient information to justify such an expectation.

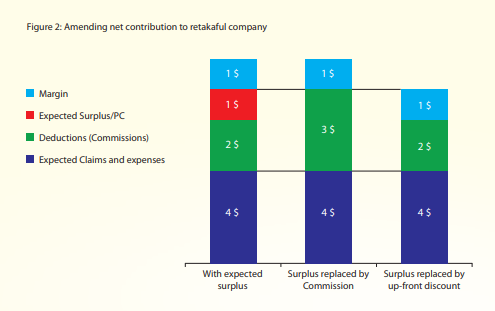

Furthermore, there is no apparent reason (except solidarity, see below) for a takaful operator to transfer a retakaful contribution, which itself contains expected surplus, from its fund to the retakaful fund when it must assume that no such surplus will be subsequently transferred to it at a later date. The retakaful operator may maintain that the quality of the portfolio is such that a surplus is to be expected. However, that cannot be justified to the takaful operator other than by blind trust or a track record of the surplus redistribution for earlier years, which, as far as we know, no retakaful operator so far provides. It would be tempting for the takaful operator, instead, to ask for a discount either in the gross retakaful contribution or in the net contribution, because it would then know what it was getting. The option of reducing the net contribution means that the retakaful deduction (commission) is increased, or in other words, the retakaful operator would just reshuffle two items in its pricing result, reducing the expected surplus at the expense of the fixed up-front commission, as shown in Figure 2. Even if we assume a spiritual and Islamic rationality – solidarity with the other companies (competitors) in the retakaful fund- there might be no change in behaviour

because the same solidarity should prevail with the participants in the takaful fund, at whose expense of unnecessarily high retakaful contributions would be paid.

Finally, takaful operators that consider themselves less profitable and unlikely to produce a surplus on their own would find any general pooling approach appealing, a mechanism that would lead to anti-selection.

This detailed analysis seeks to show why, as stated above, the ruling on surplus pooling is not comprehensive enough. Surplus redistribution is just one pricing element among others. Prohibiting individual surplus does not lead to an allocation advantage and it induces evasive manoeuvres that compensate for the effects of one pricing element via the others. In Figure 2 surplus-dependent commission is replaced by fixed up-front commission thereby involving a loss of pricing accuracy. The conclusion is that every individual pricing is tantamount to building an individual sub-pool. The only kind of pooling that could be considered unlimited would occur if participants agreed to cover any loss incurred by any other member, whereby everyone contributes according to their ability and not according to the kind and amount of risk (if any) they had brought into the pool.5 Only then are commercial and opportunistic aspects, together with the very functionality of insurance, totally ruled out. However, as long as contributions paid are supposed to be commensurate with the risk ceded, prohibiting sub-pooling does not really change the system. It does, however, narrow the range of available pricing parameters.

Other ongoing debates: windows and cooperatives

While there are apparent changes in technical concepts, and standards are being reviewed or elaborated in the Gulf and Malaysia, new markets are opening and regulators seem to be preoccupied with a somewhat different agenda. The new takaful markets of Tunisia and Oman, as well as the more mature ones in Qatar and Pakistan, have recently issued decisions on the legitimacy of window operations, though only Pakistan is inclined to allow it subject to certain conditions, while the other regulators decided against it. The arguments behind this may be summarized as follows: stand-alone companies are considered to be a cleaner and more credible approach, while windows have the advantage in that established conventional players can support the spread of takaful by using synergies with their conventional structure, personnel and, above all, distribution network. However, the practice is currently not very clear. Malaysia, for example, long ago allowed banking windows but prohibited insurance/takaful windows,6 a fact that has not prevented the Malaysian market leader Etiqa from explicitly offering “Insurance and Takaful” under one brand and strategy, although within legally separate entities. The Pakistani draft requires conventional companies to maintain separate, dedicated managers for their takaful windows, but not separate staff.

There is indeed little detailed guidance and definition of aims upon which to decide the question of whether to allow and, if allowed, how to structure windows. Why is a takaful subsidiary of a conventional company allowed, but a dependent unit or department prohibited? If this principle were taken to the extreme, no Islamic financial institution would be allowed to have any conventional shareholder or owner. Where is the limit of required organisational independence? Or, to summarise these questions, what is the relationship between substance and form?

As for structure, more clarity is also needed on processes: Is the separation of management staff, as required in the Pakistani draft, the right way or should the operational staff, the process owners, be separated, and to what extent? Are there limits on reliance on partnerships and outsourcing even for stand-alone companies? Or, to take yet another dimension, is the Shari’a governance structure to be strengthened? As an example, Munich

Re’s approach is based on knowledge and its transfer, i.e. mentoring and training all conventional staff involved in takaful-related procedures.

Surely, in light of the OIC Fiqh Academy having declared all kinds of conventional insurance unlawful, windows would never be more than a solution for a transitional period. On the other hand, the obligatory separation of funds and the rules of Shari’a governance apply as much to Windows as to stand-alone companies, if not even more so, and in that sense, windows are not less Shari’a-compliant. So, one question arising out of the above is if, and as long as conventional insurance companies are allowed, why should conventional companies that have Islamic windows be prohibited or limited in their lifespan? It may be worthwhile restarting a debate in order to define the essence of windows, their purpose and their positive or detrimental effects more clearly.

A further point should be taken into consideration. During the financial crisis, lessons were learnt regarding the shortcomings of conventional financial institutions, and regulations are being considered in many Western countries aimed at increasing stability, transparency and sustainability and avoiding speculation and gambling. The notion of risk-free returns, the basis of traditional portfolio theories, has proved to be questionable. All these aims and values are also behind the Shari’a rules. Western mutual insurers are already considered by scholars to be the closest to takaful, or at least the lesser evil. It would not require substantial changes to make them fully compliant. In turn, takaful bodies are reviewing their standards and basic terms. The Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency (SAMA) has declared the cooperative system to be Shari’a-compliant but not takaful. Is it possible that ultimately the conventional and takaful worlds will move closer to each other in practice and even in theory? There are obstacles that are still hard to overcome, e.g. the Gharar ruling on bilateral exchange contracts. Also, conventional insurers would have to do more than make a few changes to become Shari’a-compliant, e.g. modify their investment strategies. It may not seem likely at first glance, but it is not inconceivable for the Islamic finance industry to be a vanguard and have a positive, though selective, impact on its conventional counterpart if they are prepared to see themselves in that role. This could be one of the outcomes of the process of becoming self-aware, the coming of age.