Introduction

The recent financial crisis that affected many countries has prompted a call for revision and review of current financial practices. Among the reforms called for were improved corporate governance, disclosure, transparency, regulatory supervision and risk management. These developments have, to a certain extent, triggered market participants to examine the loopholes and the areas that need improvement in the Islamic finance industry. One of the areas that standard-setting bodies and regulators have identified as needing improvement is the Shari’a governance aspect of Islamic finance. Obviously, Islamic finance is subject to a variety of regulatory standards as well as standards of prudence and corporate governance issued by a number of different bodies. However, Shari’a matters are unique to Islamic finance; they have no role in conventional finance. Since the inception of Islamic finance, Shari’a matters have been the concern of the Shari’a authorities within the industry. These include the Shari’a department of any particular financial institution, Shari’a scholars and the National Shari’a Advisory Council in the jurisdictions that have one, such as Malaysia, Pakistan and Sudan. The time has come for a solid framework to be put in place for Shari’a governance, because the Shari’a is considered the core element of Islamic finance, without which the whole industry will be in danger. The integrity of any Islamic financial product greatly depends on its compliance with the requirements of the Shari’a, and any deficiency in this aspect will surely affect the market and stakeholder confidence. This chapter will highlight the importance of Shari’a governance and look at the challenges to providing a robust Shari’a governance framework as well as possible solutions.

Shari’a governance

Shari’a governance can be defined as the process and mechanism that will ensure that an IFI not only complies with the Shari’a in its operation and offerings, but that it also achieves the objectives of the Shari’a.1 The governance process Shari’a, includes the processes and mechanisms in the following areas:

- Shari’a advisors

This includes the qualifications for appointment as a Shari’a advisor, the duties and roles of Shari’a advisors, their mandate, conflicts of interest, independence, transparency, etc.

- Financial institutions offering Islamic financial products

This includes their duties and roles, relationship with the scholars, obligations regarding Shari’a decisions, implementation, management of Shari’a matters, etc.

- Shari’a governance framework

Shari’a governance involves the setting up of a clear and comprehensive framework of governance to regulate the current Islamic finance industry and its future development. Shari’a advisory Shari’a or supervision over IFIs is not regulated in some jurisdictions (Wilson, 2009). Thus, a clear and comprehensive framework of Shari’a governance is lacking, which raises concerns about the effectiveness of the supervision performed by the Shari’a advisors in those countries. Effective governance of the industry would require defining the main actors, namely the Shari’a advisors, their responsibilities and the roles they need to undertake for the well-being of the whole Islamic finance sector. From a regulatory perspective, there has been a focus upon four elements that need tobe ingrained in the scholars for a comprehensive Shari’a governance system to be established. They are: competence, independence, confidentiality and consistency.

Shari’a advisors must be experts in Shari’a, especially in fiqh mu’amalat (laws of transactions), and should also possess an adequate understanding of finance, both conventional and Islamic. In order to ensure high-quality Shari’a decisions, Shari’a advisors should also possess deep understanding of Maqasid al-Shari’a, have the ability to conduct research and derive legal rulings, have sufficient understanding of various Shari’a issues in Islamic finance and possess good personal qualities such as boldness, trustworthiness and dynamism. As for the duties of Shari’a advisors, they should include involvement in designing the framework for the establishment of IFIs, giving advice to existing IFIs on matters pertaining to Shari’a issues, monitoring the activities and procedures of such institutions, developing products and underlying contracts, acting as the reference for Shari’a matters for an IFI specifically and for the Islamic finance industry in general, providing training and awareness programmes for the staff of the IFI, supervising the Islamic finance industry, and representing the Islamic finance institution in forums on Islamic finance designed to exchange ideas and share experiences (Daud, 1996).

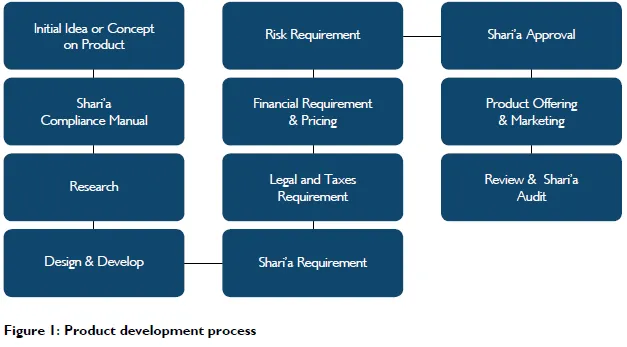

However, Shari’a advisors are mostly known for their involvement in approval of products. Nevertheless, it should be realized they are not kowtowers who will endorse whatever that comes to them. Endorsement has to be done after full investigation and satisfaction that a product is in line with Shari’a requirements. Therefore, it is very important that they are involved in the whole process of product development as illustrated in figure 1.

In executing those roles, Shari’a advisors must observe the following:

- ensure that product development uses the acceptable principles of the Shari’a;

- ensure that the decisions of the Shari’a boards are

understood by the practitioners;

- scrutinize the documents related to products and transactions, as negligence will result in non-compliance and negative legal consequences;

- possess full knowledge of the purpose of the products and how they are applied;

- assess the economic implications of the product for the Ummah;

- strengthen the governance of Islamic financial institutions and embed Islamic values in the financial institutions’ business operations and governance.

These considerations are really important as they enhance the role of the Shari’a advisor in order for effective Shari’a governance and supervision to take place.

In relation to this matter, the efforts of a number of institutions to provide comprehensive Shari’a governance should be commended and followed. They include various fatwas and standards on Shari’a governance and auditing issued by AAOIFI, and guiding principles on Shari’a governance issued by IFSB and by certain regulators such as Bank Negara Malaysia, who have outlined a ‘Shari’a Governance Framework for Islamic Financial Institutions’ (Bank Negara, 2010).

Another factor that can help enhance the Shari’a advisors’ effectiveness is for the management and shareholders of the IFI to commit themselves to the independence of their Shari’a advisory board and to following its guidance and recommendations on best practices from a Shari’a perspective.

Moreover, the institution should assist in the establishment of a Shari’a department or secretariat within the institution to, amongst other things, assist the Shari’a board. The secretariat will render great help to the Shari’a board by providing resources, collecting fatwas and the IFI’s reports, conducting research, assisting in the product development process and in conducting internal reviews or audits or any other assistance required by the Shari’a board.

Although Shari’a governance is mainly the task of the Shari’a advisors, the IFI’s management and shareholders need to cooperate with the scholars in order to ensure the effectiveness of that framework. Several jurisdictions such as Malaysia have listed various roles and responsibilities of IFIs towards the Shari’a board. Additionally, laws friendly to the Shari’a and to Islamic finance are also significant for facilitating Shari’a governance (Djojosugito, 2008).

The importance of Shari’a governance

Governance in all its forms is important as it ensures that an institution is always on track, capable of reaching its objectives, and following its own standard procedures as well as best practices. Governance guards the venture from malpractice, controversies and adverse impact on its stakeholders. It will preserve confidence in the system; without it, confidence in the system will diminish, leading to a systemic run on the institutions and, in the end, the collapse of the system.

More importantly, Shari’a governance based on divine guidance is expected to have a greater impact on the operations of the institutions. Therefore, the roles of Shari’a advisors are not confined to ensuring that the products and services are Shari’a-compliant; rather, they should also ensure that the operations of the institution and the overall Islamic finance system are truly Islamic in spirit and that they move towards fulfilling the objectives of the Shari’a. In addition, the existence of Shari’a governance will make the institution more responsible, accountable and transparent. This is because the ultimate principle in Shari’a governance is responsibility to Almighty Allah, who observes the conduct of all human beings, whether open or hidden. Therefore, any malpractice or breach of trust by a Shari’a advisor or the management of an Islamic finance institution is considered a sin, its magnitude increasing with the magnitude of its adverse impact on the Ummah.

Effective Shari’a governance will lead to the following results:

- The products and operations of the institution will be Islamically based and will fulfil the objectives of the Shari’a.

- The management will observe best practices and taqwa (God-consciousness) in all actions.

- The shareholders of the IFI will not expect a high return only but will also participate in promoting social good.

- Islamic financial institutions will acquire added value in terms of Shari’a compliance, trustworthiness and transparency.

Therefore, effective and comprehensive Shari’a governance is very important and will be the determining factor in the uniqueness of Islamic finance and its offerings. Without it, Islamic finance will not be any different from conventional finance.

Challenges To Effective Shari’a Governance

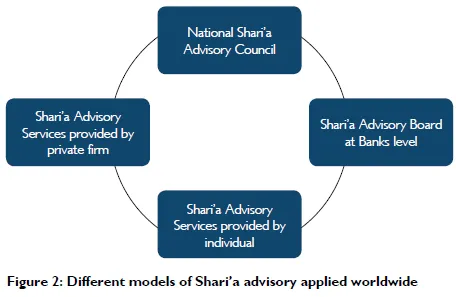

At present, it is difficult to say that Shari’a governance has been effectively applied. Several events and signs observed in the industry indicate that improvement is necessary. For instance, sukuk defaults have raised anew several unsettled Shari’a issues and highlighted uncertainty over investors’ interests (Saleem, 2010).6 In addition, several legal actions against IFIs have raised some questions over the fairness of the contracts used by Islamic finance institutions. Differences of interpretation of the Shari’a have also raised concerns in the industry about the impending Shari’a-risk impact for institutions offering Islamic financial products. In fact, there is no uniform mechanism used for Shari’a governance. At present, different models of Shari’a advisory services are applied as illustrated in figure 2.

It has been highlighted in many venues that Shari’a advisory needs to be improved and Shari’a advisors need to be better equipped. Some points of discontent with Shari’a advisory are lack of focus, adequate numbers, knowledge, experience, exposure and training. There is still a gap of knowledge between Shari’a advisors and industry practitioners; only a few scholars are finance savvy, and only a few practitioners are Shari’a savvy, although commendable efforts are being made to remedy this state of affairs with the growth of many educational and training organizations specializing in Islamic finance. Another problem is the lack of a specific institution or method for ensuring that the qualifications of Shari’a advisors are maintained or enhanced. This matter is crucial in order to ensure the validity and integrity of decisions made by Shari’a advisors.

Moreover, there is an abundance of fatwas available in the market. Although every qualified scholar can make ijtihad, how can it be ensured that the proper discipline is observed, that sufficient contemplation occurs, and that there is strong justification for every word said? As Islamic finance moves towards further growth and expansion, it requires some degree of certainty, especially with its Shari’a governance system, so that public confidence is well preserved.

Other factors that remain as challenges to effective Shari’a governance are closely related to the lFIs themselves and to the existing systems in any given country. In developing products, the Shari’a advisory has to balance and harmonize the requirements of the Shari’a and the regulatory environment, including legal, accounting, and tax requirements. Certain jurisdictions are not friendly to Islamic finance in particular or the Shari’a in general. On top of that, Shari’a advisors must take into consideration the financial viability of prospective products. Moreover, major challenges can come from the upper management of Shari’a institutions themselves, who sometimes fail to understand and appreciate unique features of Islamic finance and Shari’a requirements. It is also challenging for Shari’a advisors to make decisions for institutions that do not provide assistance to their Shari’a boards and do not disclose material information. It is also difficult for them to work in institutions that focus on monetary objectives to the neglect of Shari’a objectives.

Shari’a governance in select jurisdictions

A lot of progress has been made in strengthening Shari’a governance frameworks. Regulations and guidelines in secular jurisdictions ensure that there is a form of moni- toring and supervision. Certain countries have a more robust framework addressing the governance issues that could arise. There are three in particular which need consideration:

- The presence of a National Shari’a Advisory Council

- Fit and Proper criteria of scholars

- Conflict of interest rules

Different jurisdictions have varying approaches to the aforementioned points. A review is therefore in order to see how certain countries have addressed Shari’a governance.

National Shari’a advisory Council (NSaC)

The size of the NSAC differs between nations with Pakistan having five members (as of 2007) whilst Malaysia has 11 (as of 2008). With the exception of Brunei, the Islamic legal school of thought that the scholars are expected to follow is not stated. Provisions in Brunei statute require that indigenous scholars on the board be versed in the Shafi school whereas foreign scholars can be of a different school. Moreover, not all the members are required to be Muslim. Brunei legislation also contains procedural information regarding the meetings including quorum and voting rights.

In Malaysia and Pakistan, the NSAC is attached to the

central bank whilst in the UAE and Brunei, it is attached to governmental departments. The DFSA acts as the NSAC for the DIFC but it is not an independent Shari’a body.

Shari’a boards of IFIs are expected to report to the NSAC on a range of issues. These include

- The names and qualifications of the members

- Appointment and dismissal of members

- Disputes on Shari’a-related issues

- Transactional documentations for approval on Shari’a- compliance

Reciprocally, the NSAC will offer guidance and provide fatwas on products, which is binding. BNM is widely recognized as having one of the more advanced Shari’a governance frameworks and was one of the first jurisdictions to have a formal Central Bank Shari’a board. Recent updates to the Shari’a guidelines with regards to the fit & proper criteria of the Shari’a board has changed as was mentioned earlier. Shari’a board members are now required to posses at least a bachelors degree in Shari’a with exposure to Usul Fiqh and Fiqh Muamalat. Furthermore the new guidelines aim to improve the whole Shari’a governance process by making it necessary for each bank to establish three functions to enhance the Shari’a governance framework, which are a Shari’a risk management control function (for identifying all areas in which there is a possibility of non¬ Shari’a- compliance), Shari’a review function and a Shari’a audit function.

In contrast to AAOFI guidelines and its own previous guidelines, the new BNM framework has made it mandatory for there to be at least 5 Shari’a members per board. The guideline also recommends at least one Shari’a board member to sit on the BOD to act as a bridge between the two entities.

The UK and Singapore do not have NSACs; there- fore reliance is placed on the IFI board to offer the necessary guidance. However, both these nations suffer more acutely the problem of not having active recourse to scholars. Having a central Shari’a board is beneficial as it means the existence of an ultimate Shari’a authority within a particular jurisdiction which has the right for final approval of new products and services offered by Islamic financial institutions. According to a Mckinsey report another benefit of having a centralised Shari’a board is that it provides certainty offering a minimum level of Shari’a compliance required by legislation, which individual boards are required to follow. SSBs of different IFIs can offer contradictory fatwas, which reduces certainty in the practice of Islamic finance and can add a layer of confusion as to the merits and authenticity of Islamic finance. Furthermore as Shari’a expertise is no doubt limited, the setting up of a centralised Shari’a board enables all players to benefit from top calibre scholars who sit on the board and may reduce the burden on individual Shari’a boards as they can look to the centralised board for guidance. It is noteworthy that in pre-modern Islamic courts, judges would have recourse to high-level scholars to assist them with rulings on particular cases.

On the other hand, having a centralized Shari’a board limits the number of opinions which may affect innovation. With a centralized board, there is a real possibility that scholars will offer a particular point of view at the expense of others. The parameters of Islamic finance will therefore be defined by a parochial perspective and not have the democratic quality that is currently evident. Some bankers and lawyers have criticised8 AAOIFI proposals to set up government-level Shari’a supervisory boards to oversee Sukuk sales, as they feel it will in- crease bureaucracy within the industry.

Fit and Proper Criteria

Pakistan has a detailed set of criteria for Shari’a Advisors. Educational qualifications and experience are specific and require referential points (such as degrees from recognised universities or madrasas) Former BNM Guidelines in Malaysia required a qualification or the required level of understanding or knowledge, which may not have been necessarily confirmed by a formal academic institution. However recent Shari’a Guidelines9 have shown that now BNM requires that a Shari’a Advisor has at least a Bachelors Degree in Shari’a Law. In Pakistan, an advisor is required to have 4 to 5 years experience of issuing religious rulings, though this may be relaxed.

Members are expected to be honest, with integrity and have a good reputation, without criminal offences. Pakistan has added Financial and Solvency integrity to the criteria, whereas Malaysia has been more implicit. Malaysian rules opine that members should not have been involved in financial malfeasance or be in default for payments owed. The Bank Negara can disqualify members if it is found that members have been declared bankrupt. The DIFC require IFIs to keep documentation on:

- Factors taken to decide competency

- Qualifications and experience of the Shari’a board members

- Basis on which the IFI has deemed member suitable for the Shari’a board

Within the DIFC, the onus is upon the IFI to define what they expect from potential members of the Shari’a board.

In the UK, there are still regulatory concerns as to the role of Shari’a scholars. Regulation will differ dependent on whether Shari’a scholars are Directors or Advisors. If it the former, then they would have to follow FSA’s Fit and Proper criteria which includes competency and capability. The FSA believe that most Shari’a scholars would not meet this criterion as they would not have relevant experience.

If the Shari’a scholar is considered an Advisor, then the IFI has to show that the scholar does not interfere in IFI management. According to the FSA, the IFIs have managed to show this (as of 2007). The FSA will look at governance structure, reporting line, fee structure and terms and conditions of the contracts of Shari’a scholars in order to decide the position of Shari’a scholars.

The majority of Shari’a scholars do not have a proficient knowledge of conventional finance, which makes it difficult for them to effectively analyse and subsequently is- sue comprehensive fatwas. Initiatives such as the Islamic Finance Councils (IFC) Scholar development program are very important in ensuring that the industry has a future supply of adequately versed Shari’a scholars who are competent in both Shari’a and conventional finance. UK, Bahrain and Malaysia have recognized the importance of the program as it facilitates the connection be- tween financial practitioners and academics with Shari’a scholars and grants the latter a deeper insight into the finer, technical details of the conventional financial products and systems. Scholars have been particularly interested in how Islamic products can be structured to produce a competitive return without contravening Shari’a tenets.

Conflict of interest rules

Pakistan’s legislation is strict. A Shari’a advisor is not allowed to work within a Shari’a board of another IFI and cannot hold an executive or non-executive role. A Shari’a Advisor should neither have any substantial interest (5% or above) in the business of or be an employee of a: (a) Exchange Company (b) Member of Stock Ex- change, and (c) Corporate Brokerage House.

However, these rules are only for Shari’a advisors. If a bank is to constitute a board, members can be part of boards of different IFIs. The Shari’a board of Meezan Bank and Bank Islamic Pakistan have the same scholar on both boards. Moreover, a member of the Central Shari’a board can be member of an IFI board. This is not permitted in Malaysia.

In Malaysia, a Shari’a scholar cannot sit on the various boards of IFIs within the same industry. Therefore, he or she can be on the board of a retail bank and also on the board of a Takaful institution. In the DIFC, the only requirement is that Shari’a scholars s are not a Directors or Controllers of the IFI. However, details of other boards the scholar is part of or has been part of needs to be provided. Any conflict of interest has to be conveyed to the governing body of the IFI. If they are unable to handle the conflict, the member has to be dismissed and/or replaced.

The FSA have stated that if Shari’a board members are considered as being Directors, then it is more likely they will be considered as Executive Directors due to their active participation in IFI business. If this is the case, then sitting on different boards will create significant conflict of interests which would be contrary to the rules and regulation of the FSA.

At this juncture, it is convenient to look at the recent Funds@Work/Zawya study on Shari’a scholars. One of the key findings was that in an industry with over 300 scholars, there are 20 highly sought of scholars who sit on 54% of the Shari’a boards. In the top 20, many are sitting on up to and over 30 SSBs. This is largely due to their expertise, credibility and shortage of qualified and experienced Islamic finance scholars within the industry. Critics, contrarily, argue that this is creating a cartel-like market and reducing opportunities, decreasing both efficiency and the potential for innovation and growth. Not only is there scope for conflicts of interest but more worryingly a derogation of duties. There will be increased pressure on scholars to report on time, which leads to inefficiency due to superficial reading of the documents or outsourcing to individuals or institutions without the requisite experience. The report also revealed that there is a probability of 80% for two of the leading top ten scholars sitting on the same board. Problems of collusion leading to a conflict of interest may arise though this is more a presumption as there is no evidence that this has occurred. Another concern is once again the reliance on only a small group of scholars thereby reducing the opportunities for new scholars to develop experience and knowledge.

Looking at the codes of conduct of lawyers or accountants, there are strict and stringent rules in place in order to reduce the potential of conflict of interest. The Islamic finance industry cannot ignore best practices adopted by the conventional finance industry as these have been developed from years of experience. As a nascent industry, it has to learn from mistakes of the conventional financial industry, and act accordingly. To stimulate change however, impetus should be placed on the leading group scholars to devise a systematic method of introducing a critical mass of new Shari’a scholars into the industry. Conflicts of interest can be reduced thereby improving the integrity of the industry. It allows the transfer skills and knowledge from a talented cabal of scholars to a wider group of up-and-coming scholars, and provides opportunities for them to get into the industry.

Solutions

Various initiatives have been executed to address these challenges; for example, various educational institutions are offering Islamic finance courses. In addition, universities specialized in Islamic finance are being started to prepare a new generation of Shari’a advisors and to equip them with the necessary knowledge and exposure. Also, existing Shari’a experts from academia are being invited to join Shari’a boards of IFIs, which are providing them with training and exposure. As a matter of fact, some regulators have required institutions to provide continuous professional development programmes to Shari’a board members. Such initiatives will address the problem of the shortage and competence of Shari’a advisors. The fruits of these efforts will be seen with the passing of time.

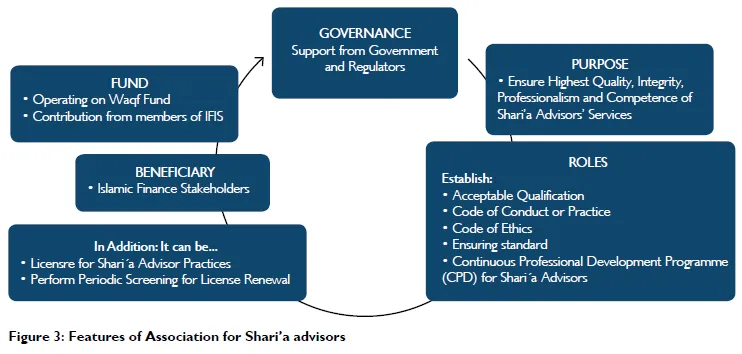

Apart from the existing efforts, it is proposed that a professional body or organization for Shari’a advisors be initiated to oversee their practices and conduct, for they are part of a profession that requires public trust as well the highest levels of integrity and competence. Such a body would regulate the Shari’a advisory industry, organize and ensure the continuous professional development (CPD) programme for Shari’a advisors, establish an acceptable qualification standard for members and oversee their conduct. It may also be given a mandate to issue professional certification to Shari’a advisors that would allow them to practice and to determine the renewal of that certification by periodic review and screening, to ensure that the Shari’a advisor is competent and at all times exercises the best professional, educational and ethical conduct. The features of the proposed organization can be seen in figure 3.

Challenges involving the existing system in a given country will require serious attention and commitment by the government and regulators to prepare a supportive environment for the advancement of Islamic finance. As for challenges posed by IFIs, greater participation of Shari’a advisors and regulators is required in order to influence them to change their stand and current practices. For instance, Shari’a advisors will need to propagate the importance of Shari’a governance and the institution’s participation in ensuring its performance. This will include explaining to the institutions the added value that they will posses and the benefit that they will be able to give to the society.

As for regulators, the commendable efforts of IFSB and BNM need to be followed. They have issued lists of actions that IFIs must take in order to ensure effective Shari’a governance. For instance, in the ‘Guiding Principles on Shari’a Governance Systems for Institutions Offering Islamic Financial Services,’ issued by IFSB (2009)10, The IFSB have defined a Shari’a Governance system as ‘A set of institutional and organisational arrangements through which an IIFS (Institutions offering Islamic Finance Services) ensure that there is effective independent oversight over each of the following structures and processes:

- Issuance of Shari’a resolutions that govern the whole of its operation;

- Dissemination of Shari’a resolutions to operative personnel who monitor day-to-day compliance;

- An internal Shari’a review unit which verifies Shari’a- compliance;

- An annual Shari’a review ensuring that the internal review has been appropriately carried out.

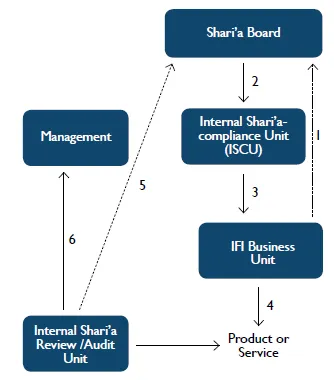

The IFSB envisages the Shari’a governance system to work in the following way:

- A business unit in the IFI will provide the Shari’a board with documentation upon the technical structure of the product or service they wish to offer

- The Shari’a resolution will be determined by deliberation between members of the Shari’a board who may advice on amendments in order to make the product Shari’a-compliant. The Shari’a board provides the ISCU or a Shari’a advisor with its pronouncement. The ISCU monitor day-to-day compliance and should be independent and separate from the IFI’s departments and business units.

- The ISCU disseminates the resolution to the business

- unit that required guidance

- The business unit offers the products onto the market

- Shari’a audits will be undertaken by an internal Shari’a review unit, as part of the IFI’s compliance team. The unit will review the products and services and see if they adhered to the opinions of the Shari’a board. The unit reports to the Shari’a board.

- In the event of non compliance, the internal Shari’a unit will recommend management to address and rectify issues of non-compliance.

The IFSB recognize that any rigid rule-based approach to Shari’a governance may act as a hindrance. The rules are to complement other standards by IFSB11 and regulatory policies of different jurisdictions. There is no one size that fits all but the system should be commensurate with the size and nature of the business.

Underscoring this structure, it has outlined the following principles:

Principle 1.2 declares that the Islamic finance institution has to ensure that its Shari’a board shall have clear terms of reference regarding its mandate and responsibility, well-defined operating procedures and lines of reporting, and good professional ethics and conduct.

Principle 2.1 requires that those overseeing the Shari’a governance system shall be at all times qualified, competent and possess good character to perform their respective roles. They shall include the dedicated officers or departments assigned to assist the Shari’a board and its members in their functions.

Principle 2.2 directs IFIs to facilitate continuous professional development for the Shari’a board and its officers, whilst Principle 2.3 mandates institutions to assess the performance of the Shari’a board, its contributions and commitment. These principles touch on the element of competence of the Shari’a board and its officers and how it can be attained and enhanced. Implementation of these recommendations is very important, and it is the responsibility of the Shari’a board to ensure that they are competent and worthy of the trust and responsibility bestowed upon them.

Principle 3.1 reminds the Shari’a board to be free from conflict-of-interest issues and that they must at all times be capable of exercising independent and objective judgment.

Principle 3.2 requires the IFI to provide complete, sufficient and timely information and resources to the Shari’a board. That shall include access to legal, accounting, financial or other relevant advice to assist in the execution of their duties. Para 51 asserts that the Shari’a board shall have access to all relevant data on the institution, even if it is confidential.

Apart from the above, there remains the challenge of harmonization and standardization of different legal interpretations of the Shari’a (Hassan, 2010).12 The issuance of various standards and parameters by standard-setting bodies such as AAOIFI and by relevant authorities as well as the development of various standard documents by different parties has contributed towards its resolution. Since standardization takes a long time to materialize, the focus should be on harmonization. In this respect, it would be helpful for various Shari’a boards to disseminate their Shari’a resolutions together with their justifications, as that would promote mutual respect.

The way forward

There are several pressing issues that need to be understood by the parties involved in Islamic finance in order to maintain the high quality of Shari’a governance in the near future. These issues include:

- Shari’a legal rulings (fatwas)

Recent events and dialogue in the industry indicate misunderstanding or lack of understanding of the nature of fatwas. Shari’a legal rulings (fatwas) are a result of scholars’ best efforts to derive the ruling of Allah for certain issues after necessary investigations. There are certain features of fatwas that must be understood. Tradition- ally, a fatwa is not binding unless it is declared part of the existing law by the relevant authority. However, to assure Shari’a compliance, Shari’a governance and the Islamic finance framework or law may prescribe that resolutions issued by Shari’a boards are legally binding upon the IFIs.13 A fatwa issued may be reviewed if it is found that the circumstances in which it was issued or the market conditions have changed (Al Zuhaily, n.d).14 This is in line with the principle of the Shari’a that rul- ings can change with changes of time and circumstances (Al Zarqa, 1993).15 In addition, a certain fatwa might be issued for a specific situation, and it will cease to be in force when the circumstance no longer exists. Such a policy is necessary, as the legal opinion of a jurist must always take into account the changes that happen in the market. Nevertheless, a fatwa’s effect can only be pro- spective, not retrospective. Careful procedures should be applied for reversal of a fatwa so that adverse effects do not result.

Similarly, differences of interpretation in issuing fatwa are not strange in the tradition of Islamic legal thought; rather, this has been a common phenomenon throughout Islamic legal history and is known as ikhtilaf al fuqaha’ (differences of opinion among jurists) (Al Zuhaily, n.d).16 This is because fatwa is affected by differing perceptions of scholars toward certain legal principles and their applications on the ground. It is also influenced by the de- tailed evidence they had knowledge of. Notwithstanding that, diversity of opinion among scholars has always be- ing considered as a blessing because it enriches Islamic law and provides various perspectives and solutions for various issues. Therefore, diversity of opinion should not be considered a vice but a strength that Islamic finance can leverage on for wider applications and acceptance.

- Fatwa issuance approach

It is vital for Shari’a advisors to apply moderation (al- wasatiyyah) in resolving and arriving at Shari’a decisions

on issues related to Islamic finance. This means that the scholars shall investigate the issues and arrive at a decision without compromising the fundamentals of the Shari’a.17 As for the interpretations, they might vary from one situation to another, depending on the circumstances and prevalent practices, as well as the needs of the industry and the society as a whole. Imam al-Shat- ibi (1997) emphasized the importance of moderation, when he said, “A virtuous mufti is the one who provides moderate and practical solutions for the public and does not burden them with unnecessary burdens (al-shiddah) and will not also be inclined towards excessive flexibility (to the point of compromising Shari’a principles)”.

Apart from this, it is pertinent that fatwas be issued based on adequate and reasonable justifications. There- fore, it is important that sufficient research be conducted prior to a resolution on an issue by a Shari’a board. Only then can it be composed. That is so all the Shari’a decisions or resolutions are made with due diligence and with utmost good faith.

- Legal documentation

Recent developments in Islamic finance and laws have highlighted the need for clarity in Islamic finance legal documents, standard contracts and in the terminology of Islamic finance.

It is feared that transactions and products developed on sound Shari’a principles are not clearly manifested in the contracts and may give rise to different interpretations or be vulnerable to challenge in court. Thus, the clarity of Islamic finance legal documents is very pertinent so as to ensure that they do not cause disputes between the parties and that the terms and conditions of the contract will be honoured. In addition, that will assist judges in understanding the transactions and providing just resolution to the parties.

Another method to resolve such risk is development of standard contracts. Standard contracts and terminologies are also regarded as crucial in the industry as they will boost understanding and uniformity in Islamic finance practices and increase the speed of Islamic of- ferings as well as avoid disputes between parties. Some parties such as the IIFM and the Association of Islamic Banking Institutions of Malaysia (AIBIM) are currently working towards producing standardized documents.

- Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) in Islamic finance

The application of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) methods to Islamic finance is another pertinent tool for addressing the ever-increasing disputes related to Islamic finance. Moreover, Shari’a advisors and scholars will be engaged as the arbitrators or mediators in Islamic finance disputes. This completes the value chain of Shari’a governance. As a matter of fact, on many occasions disputes are brought to the civil courts, whose judges do not understand the Shari’a, which leads to different interpretations by the courts or a decision that an Islamic finance transaction is null and void.

Conclusion

Additional aspects that need to be observed so that the value chain of Shari’a governance is complete include legal documentation and litigation. Nevertheless, effective Shari’a governance is not solely the responsibility of Shari’a advisors; rather, all of Islamic finance’s stakeholders must take part in it; everyone must do whatever they can to ensure its performance. Flaws in Shari’a governance cannot be easily tolerated; they pose a grave reputational risk and Shari’a risk to the Islamic finance industry as a whole. Therefore, the existing Shari’a governance practices can still be improved with the participation and contribution of various parties. It is timely that “Shari’a based” becomes the main consideration or driver of the industry and not merely “Shari’a-compliance”. It must be realized and seen that Islamic finance is not just another form of finance; rather, it is a financial system that operates based on divine guidance that will provide best services to its clients.