Introduction

During 2010, the Republic of Ireland amended its taxation laws to accommodate Islamic finance more favourably. These amendments were aimed to give Islamic financial structures and transactions the same tax treatments as their conventional counterparts.

For the benefit of those who are not very familiar with the Republic of Ireland, it is a small scenic country located on the island of Ireland at the western border of the European continent. The total population of Ireland is estimated to be slightly less than 4.5 million as of 30th April 20101. According to the official census carried out in 2006, the total Muslim population in Ireland was estimated at around 32,500.

Given the above, one might be wondering why Ireland would change its taxation laws to accommodate Islamic finance and, even if they did, what would be the interest of IFIs in Ireland? It might therefore be useful to give a high-level summary of the attractiveness of Ireland as a financial centre and the benefits that should now be available to IFIs by considering Ireland in their various investment structures.

Ireland as a financial services centre

- Ireland is a long-standing member of the European Union (since 1973) and is an established gateway to the European Union (“EU”).

- The EU operates on a single market concept. Various EU directives allow free movement of goods, capital, services and people within the Union. Using these directives, it should be possible for an Ireland-based IFI to sell its services in other EU countries, either on a cross-border basis or by setting up a physical presence there, without seeking any second authorization. The authorization from the regulatory authorities in Ireland should suffice.

- Ireland is only the second country in the EU (and the only country in the Euro-zone) with English as the official language.

- With the growing focus on regulatory matters, the European regulatory oversight which can become available on using an Irish entity in the structure should enhance the comfort of investors.

- While Ireland remains one of the founding member States of the OECD, the corporation tax rate (12.5%) in Ireland is the lowest amongst the OECD countries. Furthermore, it should be possible for an Irish company to offset any foreign taxes paid against its Irish tax liability. Ireland has consistently followed its investment-friendly policies. Despite the recent financial turmoil, all the leading political parties in Ireland have supported the decision of not changing the corporation tax rate.

- An Irish-regulated fund does not pay any tax in Ire- land. Moreover, income or gains received by non-Irish residents from an Irish-regulated fund, whether as distribution or as capital gain on a disposal of the investment, should not be subject to any Irish tax.

- Ireland has an attractive securitization regime. It should be possible to structure the transaction in such a way that an Irish securitization vehicle only pays a nominal amount of tax.

- Ireland has a well-tested agency banking model which allows the investors to substantially reduce the upfront establishment cost and avoid long-term commitments (such as leases). This is typically achieved by renting most of the systems from a reliable third-party supplier (another banking company). The use of this mechanism in start-ups provides the opening of an easy and cost-effective exit, if for any reason the investors decide to pull out. Of course, the set-up of the bank’s own infrastructure remains at the discretion of the investors. Typically, foreign banks would start with an agency banking model and gradually shift to their own systems.

The above reasons have helped Ireland develop itself as an established international financial services centre. This has also helped Ireland develop a deep pool of local expertise in the financial services sector. The follow- ing key statistics evidently support this fact.

- Ireland is considered the home of aviation leasing and finance. Along with the US, Ireland is the world’s largest aviation leasing centre. It has more than 3,000 aircraft and engines under management with an estimated value of over USD 100 billion. undertaken through efforts and deployment or resources is considered trading in nature.

- Trading income is broadly measured under the ac- counting principles (IFRS or Irish / UK GAAP) under which the financial statements are prepared. Certain capital assets qualify for capital allowances (tax depreciation) at 12.5% on a straight-line basis, as opposed to accounting depreciation which is added back to the accounting profit.

- Non-trading income is taxed at the rate of 25%. The term “non-trading income” generally refers to income that is not derived during the course of a trade. For example, interest income received on surplus cash balances held by a non-financial services company. For a company engaged in financial services trade, one would not expect any income classed as non-trading income. However, there can be situations where a financial services company is held as deriving non-trading income, such as, if a company receives income after it has ceased to trade.

- Ireland is also considered a location of choice for setting up investment funds. The total value of fund assets under administration in Ireland is estimated at over USD

2.4 trillion2 (1,784 billion Euros).

The above only provides a bird’s eye view of the opportunities available in Ireland. While the Irish domestic banking sector might take a little while to recover, the availability of the international trading platform remains isolated from the domestic banking issues. In summary, the market for an IFI setting up its base in Ireland would not be restricted to Ireland. It should allow the IFI to expand its wings and cover the entire EU market. Ireland should be seen as an excellent provider of an enabling platform. It should not be considered a market in itself.

Ireland and Islamic finance

With the above summary, it is now appropriate to discuss the key Islamic financial products as to how they can be structured using Ireland and its matchless economic offerings. Note that where references have been made to Shari’a-compliant returns being treated as interest for tax purposes, the reference is only used to identify the same tax treatment for Shari’a-compliant returns and interest under Irish tax law. The return itself should in no way be misconstrued as interest.

Key tax principles of Irish tax law

The key principles of Irish tax law relevant to financial services companies are summarised below.

- Trading income of companies is taxed at the corporation tax rate of 12.5%. The term trading is not conclusively defined in Irish tax law. There is however a considerable amount of case law available on the subject. Fundamentally, income earned from activities that are

- Capital gains are taxed at 25%. However, there are various exemptions available to non-resident investors and situations where a charge to CGT does not arise. For example, a charge to CGT should not arise to a company where it has held more than 5% of the shares of the investee trading company for more than 12 months.

- The general VAT rate in Ireland is 21%. However, financial services are generally exempt from VAT.

- Stamp duty rates depend on the nature of instrument conveying the transfer of interest in the underlying asset. For example, a transfer of shares in a company would attract stamp duty at 1%.

- Irish tax law contains group relief provisions whereby tax loss of a group company can shelter taxable income arising in another group company. Similarly, group relief provisions are also available for capital gains tax, VAT and stamp duty and these help avoid tax costs on intra-group transactions and transfers of assets.

taxation of Islamic financial transactions

It should be noted that the economic substance of Shari’a-compliant transactions discussed in this chapter is not very different from their conventional counterparts. However, as the return under Islamic arrangements is not in the form of interest, Shari’a-compliant transactions are structured differently to their conventional counterparts. As the Irish tax system follows a form-based approach rather than a substance-based approach, these different arrangements could result in a different tax analysis than the one for a comparable conventional structure.

- Tax Briefing Issue 78

In October 2009, the Irish tax authorities published guidance in Tax Briefing Issue 78 which essentially confirmed that certain Islamic financial products and transactions notwithstanding their form will be taxed in Ireland in a similar manner to existing and comparable financial products and transactions.

The briefing confirmed that Shari’a-compliant investment funds will be taxed in the same manner as conventional investment funds; an ijara transaction (which is similar to a leasing or hire purchase arrangement) will be taxed in the same manner as conventional leasing or hire-purchase transactions and that a takaful or retakaful would be treated in the same manner as an insurance or reinsurance transactions.

- Finance Act 2010

The Finance Act 2010 introduced additional and important amendments to the Irish tax law, the Taxes Consolidation Act, 1997 (“TCA 1997”) to deal with other Shari’a-compliant products and transactions which were not clearly covered under existing law and therefore not covered by Tax Briefing Issue 78.

The new provisions refer to various Shari’a-compliant transactions as “specified financial transactions”. A specified financial transaction must be carried out at arm’s length and involve a “finance undertaking” or a “qualify- ing company”. A finance undertaking is defined as:

- a financial institution, as defined in Irish tax law. This broadly covers most banking companies and credit institutions licensed by the central bank.

- a company whose income consists of either or both income from (a) the leasing of plant and machinery and

(b) income from specified financial transactions.

As defined, the term finance undertaking does not cover conventional financial services trading companies (excluding financial institutions and leasing companies). Apparently, such companies currently cannot avail the special provisions enacted for Islamic financial transactions. It is however expected that the legislation will be suitably amended to extend the scope of this definition. However, until such time as the legislation is amended, it is recommended that any financial services trading companies (other than financial institutions and leasing companies) intending to enter into Islamic financial transactions should seek prior clearance from Irish Revenue authorities on the applicability of the tax provisions specific to Islamic finance. The Irish tax authorities are generally very business friendly and one would expect them to favourably consider a genuine application (that is not just tax motivated) on this point.

A qualifying company is defined as a company which:

- is resident in Ireland,

- issues investment certificates (sukuk) to investors, and

- redeems the investment certificates after a specified period of time

The legislation categorises the specified financial transactions into the following three types:

- “deposit transactions” (mainly banking deposits) – the amount of Shari’a-compliant return is referred to in the legislation as “deposit return”,

- “credit transactions” (mainly loans and mortgages) – the amount of Shari’a-compliant return is referred to in the legislation as “credit return”, and

- “investment transactions” (mainly sukuk) – the amount of Shari’a-compliant return is referred to in the legislation as “investment return”.

Broadly, the return paid and received under a specified financial transaction should be treated in the same way for tax purposes as interest. Therefore, in the context of a trading activity, the return would be taxable at 12.5% or deductible as a trading expense. In the context of Islamic bank deposits, the deposit return should be subject to the same tax rules that apply to conventional bank interest. Similarly, in certain specific situations where the deductibility of interest is available on a paid basis, the same treatment should apply on the amount of credit return paid in the relevant accounting period, provided the other relevant conditions are complied with.

The Irish VAT legislation has also been amended to confirm that those specified financial transactions that correspond to financial services are to be treated as ‘financial services’ for VAT purposes. Essentially, this means that those Islamic financial arrangements that correspond to conventional financial arrangements should be considered as VAT-exempt financial services.

Irish stamp duty legislation has also been amended. However, at this stage, the amendments made are restricted to the issue, transfer and redemption of Islamic bonds (sukuk). A transfer of other Irish property as part of a Shari’a-compliant financing arrangement (such as a Shari’a-compliant mortgage of an Irish property) under current law could potentially entail additional stamp duty costs.

- Tax election

In order for the provisions relating to specified financial transactions to apply, the Irish law requires that an election must be made by the finance undertaking. This election can be made on a transaction-by-transaction basis or in respect of all transactions that are of a similar nature. The election is actually designed to ensure that any conventional transactions that are similar in form to specified financial transactions do not automatically fall into the special regime for Islamic financial transactions. The objective is to help both, Islamic and conventional financial institutions, to make an informed choice. The making of an election is only required in respect of specified financial transactions that have been specifically catered for in the tax law. For example, an election is not needed in respect of transactions and arrangements where the tax treatment has been clarified in Tax Briefing Issue 78 (discussed earlier).

The provisions relating to specified financial transactions would not apply to any transaction unless the transaction has been undertaken for bona fide commercial reasons and does not form part of any scheme or arrangement the main purpose of which or one of the main purposes of which is the avoidance of income tax, corporation tax, capital gains tax, value-added tax, stamp duty or capital acquisitions tax.

The tax implications discussed in this chapter are specific to the finance products explained and to the manner in which they are structured. Where these products are offered to customers in a manner different from the manner explained in this chapter, the tax implications may differ.

Shari’a-compliant funds

A Shari’a-compliant fund is one that does not defy Islamic principles. The basic structure of a Shari’a-compliant fund is not very different from a conventional fund. However, the arrangement between the fund and its service providers (in particular the investment manager) is based on the concept of mudaraba, musharaka or wakala. In addition, the investment decisions of a Shari’a-compliant fund are influenced by Shari’a principles.

In common with other Islamic entities, a Shari’a-compliant fund would normally have a supervisory board comprising Shari’a scholars who can approve the structure and operations of the fund from a Shari’a perspective.

- Taxation of a Shari’a-compliant fund

Tax Briefing Issue 78 clarifies that, the taxation of funds, as provided in Irish tax laws should also apply to Shari’a-compliant funds. In summary, all funds set up after 31 March 2000 are exempt from tax. This allows the profit to accrue gross of tax. Instead, tax is imposed on a chargeable event which includes distributions made from a fund or disposal, transfer or redemption of fund units or shares.

In general, full tax exemption is available on distributions made to a non-Irish resident who has provided a specified declaration in relation to his residency status. Similarly, a non-Irish resident is not taxed on any gains arising on a disposal of fund units (or shares).

Taxation of service providers to a Shari’a-compliant fund

In a Shari’a-compliant fund, the remuneration of the service provider is determined on the basis of the arrangement between the fund and the service provider,

i.e. whether it is a mudaraba, musharaka or a wakala arrangement. Under any of these arrangements, the remuneration of the service provider would comprise a fixed fee or a share in the profits of the fund or a combination of both. In either case, Revenue have clarified in their Tax Briefing Issue 78 that income received by a service provider, including an amount which is linked to the profits or performance of a fund should be treated as fee income where it relates to duties performed by the service provider.

Indirect taxes

- VAT

As confirmed by Revenue in Tax Briefing Issue 78, the VAT analysis of a fund would depend on the activities of the fund. There is no general VAT exemption available to funds. However, an Irish investment fund with investments outside of Ireland should not be subject to any considerable Irish VAT. In addition, most services received by an Irish fund remain exempt from Irish VAT.

A Shari’a-compliant fund differs from a conventional fund, as it has a supervisory board comprising of Shari’a scholars. These scholars provide guidance on the structure of the fund and on investment and activities of the fund including the treatment of income received by the fund. The Shari’a scholars normally charge fees for their services.

The VAT treatment of the fee charged by Shari’a scholars would depend on whether the fund falls within the exemption contained in VAT law for investment management services and whether the services of the Shari’a scholars are an integral part of the overall management service. If it can be demonstrated that the services of the Shari’a scholars are an integral part of the overall management service, then it should be possible to argue that no Irish VAT arises on the fees paid to Shari’a scholars.

- Stamp duty

As confirmed in Tax Briefing Issue 78, a liability to stamp duty does not arise on the issuance or redemption of units/shares in a fund. In addition, the transfer of units/ shares in a fund is not chargeable to stamp duty to the extent that the fund is an approved investment under- taking, or a common contractual fund, as defined in Irish tax law.

The stamp duty analysis in relation to any transaction undertaken by a fund would depend on the nature of the transaction and the instrument involved.

Leasing and hire- purchase transactions

The term ‘ijara’ literally means giving something on rent and an ijara structure is principally used for leasing activities. The term ijara would normally refer to an operating lease but the arrangement can also be used to achieve a finance lease result. Furthermore, an ijara arrangement can be combined with a diminishing musharaka to structure a hire purchase transaction.

- Overview

In an ijara arrangement, the lessor either holds an inventory of assets for lease in anticipation of customer demand or acquires an asset following a specific request by any of its clients. The asset thus acquired by the lessor is leased to the customer for an agreed rent payable over an agreed period of time. The leased asset must be capable of some halal (permissible) use and the rental should be charged only from that point of time when the usufruct (the right to use) of the asset is handed over to the lessee.

During the term of the lease agreement, the asset re- mains the property of the owner who would normally assume the burden of wear and tear. The lessee may however be required to carry out the periodical (ordinary) maintenance. Moreover, if the asset is to be insured, the insurance expense must be borne by the owner. However, the cost of insurance may be factored into the calculation of the lease rental. The lease rentals should be specified in the lease agreement, although these can be fixed or variable amounts.

If the lessee defaults in making a lease rental payment, the lessor cannot charge any interest. However, the lease contract may require the lessee to make an additional payment towards a charitable cause. To enforce this, an ijara agreement would normally require the charitable payment to be routed through the lessor.

- Operating lease

A normal ijara arrangement would generally refer to an operating lease whereby the asset is returned to the lessor on the expiry of the lease period.

- Finance lease

Similar to a conventional finance lease, in a Shari’a-compliant arrangement the value of the asset is broadly recovered during the primary lease period and a nominal or token lease rental is charged during the secondary lease period.

- Taxation

A conventional operating lease arrangement can also be considered a Shari’a-compliant ijara arrangement pro- vided the other aspects of Shari’a are complied with, e.g. the leased asset is capable of some halal (permissible) use. These Shari’a aspects should not have any bearing on the taxation of the ijara contract. Accordingly, Tax Briefing Issue 78 confirms that an ijara transaction should be taxed on the same basis as a conventional operating lease.

A finance lease, from an Irish tax perspective, is treated as an operating lease unless the lessor company has made a specified claim to be taxed in accordance with the normal accounting practice in respect of all relevant short-term leases. Accordingly, a Shari’a-compliant finance lease transaction should be treated for tax purposes in the same way as if it were a conventional finance lease.

Where the lessee has made an additional payment to the lessor towards a charitable cause, Tax Briefing Issue 78 confirms that such payment will be treated as lease rental income received by the lessor from the lessee. Accordingly, the lessee may be entitled to a tax deduction provided the lease rental payments qualify to be a tax-deductible expense. The Tax Briefing also confirms that if the lessor utilises the amount paid by the lessee in making a donation to a Revenue approved charity, the lessor will be entitled to a tax deduction in accordance with the tax law provisions that grant an expense deduction when a donation is made to a Revenue approved charity. However, where a non-qualifying charitable donation is a legitimate expense of entering into the leasing transaction, it is arguable that the expense should be treated no differently than any other expense incurred wholly and exclusively for the purposes of the trade of the lessor or as an expense incurred in deriving non-trading income chargeable to tax.

Tax Briefing Issue 78 specifically states that the tax treatment referred to above only relates to leasing of plant and machinery and other chattels and does not apply to a lease of immovable property.

- Hire-purchase

An ijara arrangement which is similar to a hire purchase can be structured in either of the following two ways.

The key features of the first arrangement (commonly referred to as ijara muntahia bittamleek) are broadly similar to a normal ijara arrangement, as set out below.

- The lessee and the lessor would enter into a normal ijara arrangement. The term of the ijara would be the same as the intended term for an equivalent finance lease.

- In addition to the normal ijara contract, the lessor would promise to transfer the title of the asset to the lessee in either of the following ways.

- By way of gift (for no consideration)

- For a token or other consideration

- By accelerating the payment of the remaining amount of lease rentals, or by paying the market value of the asset

The transfer may be contingent upon a particular event, e.g., a transfer by way of gift may be contingent upon the payment of the remaining instalments.

- The promise is binding on the lessor only, whereas the lessee has an option not to proceed with the transfer.

- The promise should be contained in a separate document and cannot be taken as an integral part of the ijarah contract.

- If the transfer is subject to any stipulation, such as payment of the remaining instalments, the transfer cannot be made until the condition is satisfied, e.g. even if one instalment is unpaid.

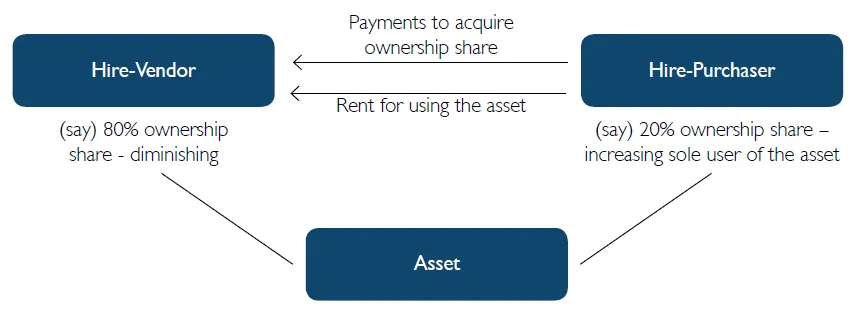

In the other arrangement, an ijara is combined with a diminishing musharaka arrangement to achieve a Shari’a equivalent of a conventional hire-purchase arrangement. This can be illustrated and summarised in Exhibit 1.

Exhibit 1

- The hire-vendor and the hire purchaser enter into an arrangement whereby they jointly acquire the asset. The asset is normally acquired in the name of the hire-vendor (as security).

- The hire-vendor’s interest in the asset is divided into a number of units.

- The hire-purchaser promises to acquire the hire-ven- dor’s interest in the asset over an agreed period (the hire purchase term) for an agreed price payable in instalments (economic equivalent of principal repayments in a conventional hire purchase). This is a binding promise on part of the hire-purchaser.

- The hire vendor’s interest in the asset is leased to the hire-purchaser. (The rentals substitute interest payments in a conventional hire-purchase arrangement)

- As the hire-purchaser gradually increases its interest in the asset by making payments towards the acquisition of the hire-vendor’s interest, there is a corresponding decrease in the hire-vendor’s interest in the asset. As a natural consequence of this decrease in the hire-ven- dor’s interest, the rental payments decrease over time. This is very similar to an amortisation schedule for a conventional hire-purchase arrangement.

- The legal title is transferred to the name of the hire-purchaser after all the instalments have been paid.

- Taxation

For tax purposes, the arrangement outlined above should be treated as if it were a conventional hire-purchase arrangement. The tax treatment of any additional payment made by the hire-purchaser to the hire-vendor (to compensate for a default in rental payment) towards a charitable cause should be the same as that set out under 25.8.

Irish Revenue have specifically stated in Tax Briefing Issue 78 that the above tax treatment would not apply to a hire-purchase transaction involving immovable property.

- Indirect taxes

Vat As confirmed in Tax Briefing Issue 78, the normal VAT

rules concerning leasing (a supply of services), transfer of title (supply of goods) or hire purchase (a supply of goods), as appropriate, would apply to the respective ijara arrangements. Fundamentally, the VAT treatment of ijara arrangements is no different from the VAT treatment of conventional leasing and hire purchase arrangements.

Stamp duty

Tax Briefing Issue 78 confirms that a charge to stamp duty should not arise in relation to operating/finance lease and hire purchase arrangements set out above where the asset involved does not comprise immovable property or an interest in immovable property.

In light of the above, the guidance previously issued by Revenue in relation to the taxation of conventional operating and finance lease transactions and hire purchase arrangements should, in substantially similar circumstances, also apply to the equivalent ijara arrangements.

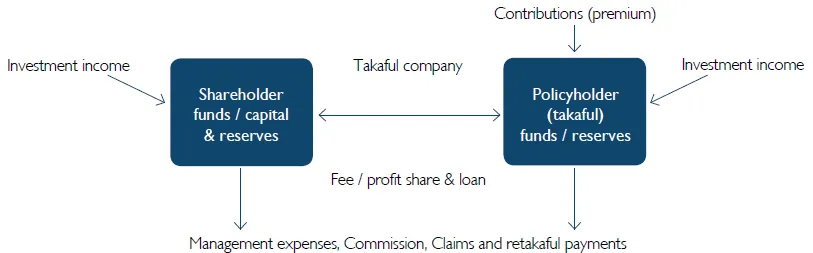

takaful (insurance) arrangements

Based on the concept of social solidarity, cooperation and mutual indemnification of losses of members, takaful is an arrangement amongst a group of persons participating in a scheme under which the takaful members (policyholders) jointly indemnify each other against any loss or damage that may arise to any of them. In broad terms, a takaful arrangement is similar to mutual insurance with the difference that takaful members would normally not be shareholders or unit holders in the takaful company, which operates the takaful fund. The company is paid a fee for its services and/or is entitled to a share in the return received on the fund’s investments. The takaful funds are invested in a Shari’a approved manner, i.e. the normal prohibitions relating to investments apply.

The term “general takaful” is normally used as a reference to the general insurance arrangement while the term “family takaful” would normally refer to a life assurance arrangement. A retakaful (reinsurance) arrangement also works in a similar way where the takaful companies assume the role of the takaful members and the retakaful company assumes the role of the operator of the scheme.

- General takaful (general insurance)

The key defining characteristics of a takaful arrangement are as follows:

- A company sets up a takaful fund and invites contributions from persons (takaful members). Takaful members pool funds by way of contributions. This fund is used to make compensation (claim) payments for any loss or damage arising to any takaful member. The claim payments are generally restricted to actual damage or loss and the opportunity costs (such as loss of potential in- come) are generally ignored.

- The takaful company operates the whole arrangement relating to (a) the management and receipt of contributions, (b) claim management and payments, and (c) the management and operation of takaful fund.

- The company tracks takaful funds separately from its own share capital and reserves. Accordingly, a loss relating to takaful funds is charged to the takaful fund and ring-fenced from the company’s reserves. Likewise, a loss relating to the company’s investments/activities is borne by the company and ring-fenced from takaful funds. Normally, the company’s share capital and re- serves (including fee income) are used to pay marketing and management expenses and commission payments.

- The relationship between the takaful company and takaful members (policyholders) can be based on the concept of mudaraba, musharaka or wakala. The recent trend is to use a wakala/mudaraba mix relationship be- tween the company and the takaful members (policy- holders).

- The company would normally charge a fee for its services relating to the management and operation of the takaful scheme and funds. The fee may be fixed or a share in the returns on takaful investments. It is also possible that the company is paid a fixed fee and is also entitled to a share in the returns received on takaful investments. The arrangement is normally set out in the insurance policy or other related documentation.

- If a shortfall arises in the takaful fund, the company would normally make an interest-free loan to the fund.

Generally, the loan is repayable only out of a future sur- plus arising in the takaful fund. If subsequently, there is a surplus in the takaful fund, the surplus is first used for the repayment of any interest-free loan owed to the company and the balance can either be reserved for future losses or the company may decide to make a distribution to takaful members (policyholders). The distribution amount may be adjusted against the contribution payment relating to the following year.

- On dissolution or winding up of a takaful fund, any surplus in the fund may be distributed amongst those who contributed to the takaful fund or amongst those who are members (policyholders) of the fund on the day of dissolution or winding up. The surplus or any part thereof may also be given to charity. The takaful funds cannot be diverted to the company.

- Taxation

Tax Briefing Issue 78 confirms that a takaful arrangement, outlined above, is broadly similar to a conventional insurance arrangement and should be taxed un- der the same provisions of Irish tax law (TCA 1997) as those applicable to conventional insurance companies. Accordingly:

- Contributions received by a takaful company from policyholders (takaful members) are to be treated as taxable income. The question whether income is on trading account will depend on the facts and circum- stances of the case.

- The deductibility of expenses incurred by a takaful company for management, marketing, claims and commissions and any provisions in respect thereof should be treated in the same way as such expenses incurred by a conventional insurance company with the same level of activity.

- The deductibility of a contribution payment paid to a takaful company is to be treated in the same way as an insurance premium for a conventional insurance policy.

- Family (life) takaful

A family (life) takaful arrangement works in a broadly similar way to a general takaful arrangement. It is similar to a conventional life assurance or a savings scheme wrapped in a life policy. The following are the key differences:

The amount received from a member (policyholder) is split between a contribution account and an investment account. The split is generally based on the actuarial valuation of the associated risks and is agreed with the policyholder at the time of issuance of the policy. The contribution account is generally reserved for life assurance claims. If the takaful member survives the policy term, the member is only entitled to receive the amount paid into the Investment account and any ac- cumulated profits attributable to such amount.

The profit made on takaful investments is apportioned amongst the policyholders (takaful members) or retained as a reserve for future. The arrangement is normally set out in the insurance policy or other related documentation, as is the case with conventional life assurance.

- Taxation

Tax Briefing Issue 78 confirms that the taxation of a family (life) takaful company, which is an assurance company, as defined, is to be determined under the same principles as those applicable to a conventional life assurance company. It also confirms that the taxation of members (policyholders) of a family (life) takaful company is to be determined on the same basis as that applying to policyholders of a life assurance company.

As a result, an amount paid by an insured person is to be treated in the same way as a payment under a conventional life assurance policy is treated. Similarly, a maturity or claim amount paid by a family (life) takaful company is to be treated in the same way as a claim or maturity payment under a conventional life assurance policy is treated.

- Retakaful (reinsurance)

A retakaful works in a similar way to a takaful. Various takaful companies participate in a retakaful fund set up by a retakaful company. In this arrangement, the takaful companies assume the role of the policyholder in a general takaful arrangement and the retakaful company acts as the operator of the retakaful arrangement.

- Taxation

As confirmed by Revenue in Tax Briefing Issue 78, the taxation of a retakaful company should be determined under the same principles as those applicable to a conventional reinsurance company. Accordingly, the tax principles outlined in 25.9.1 above equally apply to retakaful arrangements. Contribution payments made by takaful companies participating in a retakaful arrangement (and received by the retakaful company) should be treated in the same way as reinsurance premium under a reinsurance arrangement between insurance/ reinsurance companies.

- Indirect taxes

Vat

As confirmed by Revenue in Tax Briefing issue 78, taka-

ful (general and family (life)) and retakaful arrangements are to be treated in the same way as conventional non-life and life insurance and reinsurance arrangements for VAT purposes, i.e. the services rendered will be exempt from VAT. Consequently a VAT charge will not arise on service charges made by a takaful/retakaful or a family (life) takaful company to the individual or pooled contributions from the takaful members.

Stamp duty

For the purposes of stamp duty, takaful arrangements are to be treated as policies of insurance/reinsurance or life assurance, as the case may be. As clarified in Tax Briefing Issue 78, a liability to stamp duty (commonly referred to as “Insurance Premium Tax” or “IPT”) arises under stamp duty law in relation to takaful (general and family (life)) and retakaful arrangements where the risk is located in Ireland. IF the risk insured is located outside of Ireland, a charge to Irish stamp duty should not arise.

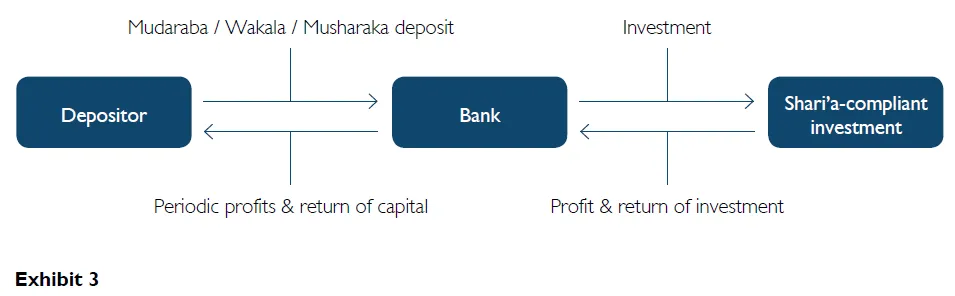

Retail banking deposits

An Islamic bank normally raises deposits using mudaraba, wakala or musharaka arrangements. Sometimes, different types of deposits are structured using different arrangements. For example, a bank may use a mudaraba model for the equivalent of a savings account and a wakala model for the equivalent of a fixed term deposit account.

In the mudaraba or wakala structures, the bank acts as the investment manager/partner or agent while the depositor is treated as the investor or principal. In a musharaka structure, the bank would mix the amount of deposit with its own share capital and reserves and utilise the pool in making Shari’a-compliant investments.

The structure of a retail banking deposit is illustrated in Exhbit 3.

The profits are shared between the bank and the de- positor on a pre-agreed ratio. Although the depositor solely bears the risk of loss in a mudaraba or a wakala structure, the bank would normally, from a commercial perspective, build up and maintain enough reserves to avoid any shortfall arising in future. Moreover, as the investments are not linked to individual deposits, the risk from a depositor’s perspective essentially becomes a credit risk on the bank. This is similar to the risk with a conventional deposit with a bank. Generally, the agreement between the bank and the de- positor allows the bank to periodically calculate and pay the share of profit according to its own calculations and estimates. It also allows the bank to carry forward as re- serves any undistributed surplus which the bank deems appropriate to provide for future losses. Normally, the agreement provides that the depositor would accept all such calculations and that the decision of the bank would be binding on him. The depositor also authorises the bank to charge appropriate fees and administrative costs and to retain the amount of the bank’s share in the profit.

- Tax treatment for the bank

The Shari’a-compliant banking deposit arrangements are referred to in Finance Act 2010 as “deposit transactions”. The tax treatment for the bank and for the depositor is set out below.

The return paid on a Shari’a-compliant bank account should be treated for tax purposes as interest and should be subject to the same tax (and withholding tax) rules as those applicable to bank interest on conventional deposits, unless the deposit return is considered a distribution under section 130 of Irish tax law (TCA 1997). Under s130, interest can be reclassified as a distribution where it is, to any extent, dependent on the results of the company. Given the profit-participating nature of many of these arrangements, Irish Revenue have issued additional guidance clarifying that deposit return will not be recharacterised as distribution solely by virtue of the profit-participating nature of the arrangement provided the transaction is expected to yield a return equivalent to an interest return on a comparable conventional arrangement and where the expected return agreed at the time of entering into the arrangement is not subsequently altered except to the extent of the movement in interest rates applicable to conventional banking deposits.

Moreover, notwithstanding the legal form of the deposit arrangement which may provide for a profit-sharing arrangement between the bank and the depositor, the de-posit arrangement between the bank and the depositor is not treated as a partnership for tax purposes.

Where the return is in excess of interest payable on a comparable conventional deposit the transaction may not qualify as a specified financial transaction and consequently the above treatment should not necessarily apply. Accordingly, the bank should not be required to apply withholding tax rules that are applicable to conventional bank interest. On the basis that the return could be considered as a share of profit paid to a partner or to the principal, the income attributable to the depositor may not be considered as the income of the bank. Partnership and agency returns may also need to be filed. Moreover, where the bank is entering into multiple partnerships, consideration would also need to be given to whether losses in one partnership can offset profits in another.

- Taxation of the depositor

On the basis that the amount of the return is not in excess of interest payable on a comparable conventional deposit and the amount should not be classed as distribution under section 130 of TCA 1997, the depositor should be treated for tax purposes as if the depositor has earned interest income from a relevant deposit taker, i.e. a conventional bank or credit institution licensed as such by the central bank. Accordingly, the depositor should be subject to the tax rules that are applicable to earning interest income on a conventional bank account.

Where the Shari’a-compliant deposit does not fall within the scope of a specified financial transaction, then, de- pending on the arrangement, the return received by the depositor could either be treated as a ‘share’ of profit from a partnership or income received by a principal from an agent acting on behalf of the principal. In either case, a resident individual could be taxed on such in- come at the marginal rate of tax, income levy and health levy and may also be subject to social security levies and charges as self-employed (where earning trading income). The tax treatment of a corporate depositor would also depend on the facts and circumstances of the depositor, e.g. whether a trade is being carried on.

In addition to the above, there could be other administrative issues. Where a non-qualifying Shari’a-compliant bank account is considered as a partnership between the bank and the account holder, partnership tax returns may need to be filed. Furthermore, while a conventional bank depositor may not be required to file an income tax return (depending on the facts and circumstances), a Shari’a-compliant depositor who is treated as receiving a share of income from a partnership (with the bank) would be required to file tax returns.

- Indirect taxes

A qualifying Shari’a-compliant deposit arrangement is regarded as corresponding to a conventional banking deposit arrangement. Accordingly, the fees levied to the depositor should be for “agency services” in relation to “the operation of any current, deposit or savings ac- count” and consequently should be exempt from VAT.

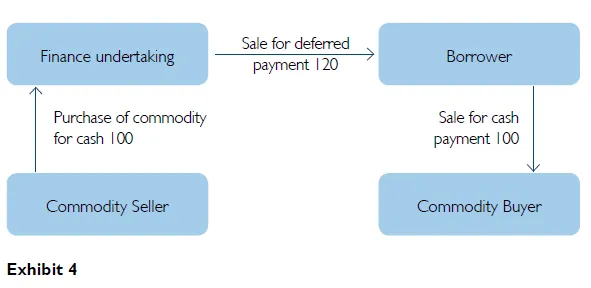

Lending arrangement and asset-backed financing (murabaha)

Typically, banks and financial institutions use a murabaha arrangement as a substitute for debt financing and asset-backed lending arrangements. The legislation refers to these arrangements as “credit transactions”. A murabaha is an outright sale, at a marked-up price, where the seller discloses its profit margin to the purchaser. The marked-up price is generally payable over time. Where the purchaser (borrower) delays in making the payment or any instalment thereof, he is required to make an additional payment towards a charitable cause. To enforce this, the agreement normally provides that the payment should be made through the finance undertaking. Under Shari’a principles, the finance under- taking should not use such payment for its own benefit and should give it away in charity.

- Debt financing

Where the objective is to raise cash, the murabaha structure commonly used is illustrated in Exhibit 4

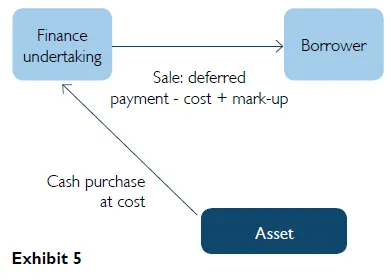

Asset-backed financing arrangement

Where the objective is to provide the Shari’a equivalent of an asset-backed financing transaction, the following structure can be used as can be illustrated in Exhibit 5.

The finance undertaking purchases a commodity for cash (for say 100) which is then sold on to the borrower on a deferred payment basis with an agreed margin of profit (say 20) inherent therein. The ‘margin’ is a substitute for interest and is generally not very different from what would be charged under a conventional lending arrangement. The borrower, immediately on purchasing the commodity, sells the commodity into the market for cash at its market value (which should again be 100). In the process, the borrower has genenated cash of 100 and has an obligation to pay 120 to the finance undertaking.

The commodity which is commonly used is copper, as it is freely traded on the commodity exchange market. Gold and silver cannot be used, as Shari’a prohibits trading in gold or silver on a deferred payment basis. Any transaction in these commodities would have to be carried out on spot.

Another approach that is also sometimes made is the sale and immediate buyback of the asset by the borrower. In the first step, the borrower sells part or all of its interest in the asset to the finance undertaking for cash. The borrower immediately reacquires the interest in the asset from the finance undertaking at a marked-up price payable in the future. As a result, the borrower generates cash and also reacquires its interest in the asset with a liability that is to be discharged in future.

Similar to the debt financing structure described above, the finance undertaking purchases the asset in the open market (or from the borrower) and then sells it back to the borrower at a marked-up price. Generally, the margin is disclosed to the borrower. The asset may then be used by the borrower while the borrower has a deferred liability towards the finance undertaking to be discharged over an agreed term.

Corporation tax

Finance undertaking’s taxation

For a finance undertaking, the tax treatment of the lending arrangement set out above should not be different from a conventional lending arrangement. In both scenarios, described above, the ‘mark-up’, being the difference between the cost and the sale price, should be treated as taxable income of the finance undertaking. Whether such income is on trading account or otherwise will depend on the activities of the finance undertaking. From a timing perspective, where such income arises on trading account, the taxable trading profits are to be computed on the basis of the accounting measure of such profits computed under Irish / UK GAAP or IFRS.

Qualifying payments made to charities by the finance undertaking should be tax deductible. Furthermore, where a non-qualifying charitable donation is a legitimate expense of entering into the murabaha transaction, it is arguable that the expense should be treated no differently than any other expense incurred wholly and exclusively for the purposes of the trade of the lessor or as an expense incurred in deriving non-trading income, where relevant.

Borrower’s taxation

For a borrower, the tax treatment of the transactions discussed above should not be different from a conventional borrowing arrangement. The markup should be treated for tax purposes as if it interested payable on a loan made by the finance undertaking to the borrower or on a security issued by the borrower to the finance undertaking, where appropriate.

On the basis that the “borrowing” is for the purposes of the trade of the borrower, the timing of the tax deduction would generally follow the accounting measure of the expense in the profit and loss account computed in accordance with Irish / UK GAAP or IFRS. Similarly, where the borrower would have been entitled to claim interest as a deduction on a payment basis if it were conventional financing, the tax deduction should be available when such return is paid by the borrower.

With specific reference to a debt financing transaction set out in 25.11, the legislation clarifies that the borrower is not entitled to claim a tax loss arising on the immediate disposal of the commodity in the market.

With specific reference to an asset-backed financing arrangement set out in 25.11, the legislation clarifies that:

- the finance undertaking is not entitled to claim capital allowances (tax depreciation) on the cost of the asset which is acquired by the finance undertaking for the purposes of entering into a credit transaction,

- the borrower is to be treated as having acquired full interest in the asset on the date of entering into the credit transaction. Accordingly, where entitled, the borrower may claim capital allowances (tax depreciation) on full cost of the asset from that date,

- the amount treated as interest is not to increase the tax basis of the asset for the borrower. Accordingly, the amount treated as interest is to be ignored by the borrower in claiming capital allowances or in calculating a capital gain or loss on a subsequent disposal of the asset, and

- where the borrower disposes of its interest in the asset to the finance undertaking and then immediately reacquires the interest from the finance undertaking, the disposal of the interest by the borrower to the finance undertaking is to be ignored for tax purposes, i.e. the disposal would not give rise to a gain or loss. The dis- posal of the interest by the borrower may potentially be subject to capital gains tax under the legislation. It is hoped and expected that legislative amendments will be introduced to address this.

For employers entering into credit transactions, as set out in 25.11 above, with their employees, the legislation specifically provides that the transaction would be treated for tax purposes as if the employer has made a loan to the employee. Accordingly, the rules relating to preferential loan arrangements should apply, i.e., there could be tax implications if the return receivable by the employer from the employee is lower than interest arising at the benchmark rate (market rate, as specified in Irish tax law).

- Indirect taxes

Vat

As the credit return is to be treated for tax purposes

as interest arising on a loan, the arrangements set out in 25.11 above should be considered as a VAT-exempt financial service relating to negotiating, giving and management of credit.

Stamp duty

On the basis that the transaction would involve goods that are capable of transfer by physical delivery, a stamp duty cost may not arise on the transaction. Where the transfer is made under an instrument, a charge to stamp duty could arise depending on the nature of goods and the instrument.

property mortgages

A Shari’a-compliant equivalent of a conventional mortgage is achieved by combining an ijara arrangement with a musharaka arrangement. This approach is commonly referred to as a diminishing musharaka arrangement. It can also be achieved by way of a murabaha arrangement. Both of these arrangements are discussed below. Shari’a-compliant mortgages are also referred to as “credit transactions” in the legislation.

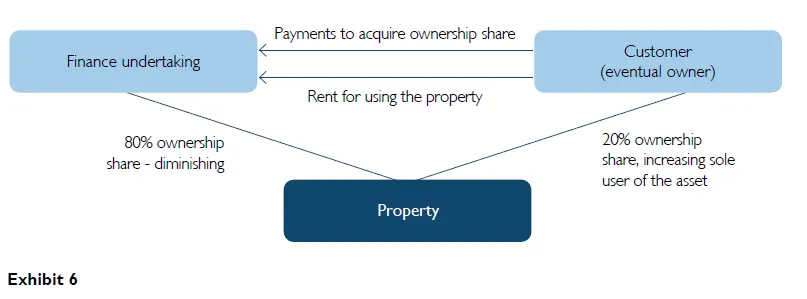

- Diminishing musharaka

A diminishing musharaka can be illustrated in Exhibit 6.

This arrangement is achieved through the following steps. Normally, these steps are achieved under different legal agreements.

- The customer (eventual owner) and the finance undertaking enter into an arrangement whereby both parties contribute capital and acquire the property (either in the market or from the customer). This can either be a partnership or a co-ownership arrangement. The respective interest of the parties is divided into a number of units. The legal title to the property normally rests with the finance undertaking, as a security.

- The property is rented out to the eventual owner who retains the sole and exclusive use of the property including the power to sub-lease. The eventual owner pays the finance undertaking rent for the lease of its beneficial interest in the property. The rent, which can be reviewed periodically, would normally be an amount equal to the economic return on the finance undertaking’s investment in a conventional mortgage.

The eventual owner promises to acquire the finance undertaking’s interest (the number of units) in the property over an agreed period of time through periodic payments. Likewise, the finance undertaking also promises to sell its interest (units) in the property to the eventual owner. The purchase price for each unit is generally agreed up front and would normally represent the finance undertaking’s interest in the cost of the property. After all the units are acquired by the eventual owner, the ownership of the asset is transferred into the name of the eventual owner.

The agreement would normally allow the eventual owner to sell the asset during the currency of the arrangement. However, this permission can be subject to a condition that the sale consideration is sufficient to fully discharge the finance undertaking’s remaining interest in the property. The finance undertaking does not gain anything from a profit made on the sale of the asset. Likewise, the finance undertaking does not take up any loss sustained on the disposal of the property. Generally, the finance undertaking would charge a settlement fee for administering the account and releasing the deeds. The amount of rent payable to the finance undertaking decreases proportionately as the eventual owner ac- quires its interest in the property. If a payment for rent or acquisition of ownership interest is not made by the due date, the eventual owner may be required to make an additional payment towards a charitable cause. To enforce this, the agreement normally provides that such payment should be routed through the finance undertaking. Under Shari’a principles, the finance undertaking should not use such payment for its own benefit and should give it away in charity.

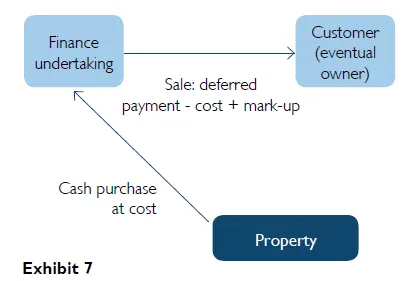

- Murabaha

The murabaha arrangement used is as discussed in 25.11. It can be illustrated in Exhibit 7

The property is purchased by the finance undertaking for cash (in the market or from the customer) and is then sold on to/(back to) the customer (eventual owner) on a deferred payment basis at a marked-up value. The amount is payable over a term which would typically be the term under a comparable conventional mortgage. The ‘mark-up’, which is determined on the basis of the term of the arrangement is the financial equivalent of an interest return under a comparable conventional mortgage. Similar to a conventional mortgage, the finance undertaking may keep a lien over the property.

Similar to a diminishing musharaka, if an instalment is not paid by the due date, the eventual owner may be required to make an additional payment to the finance undertaking to be utilized towards a charitable cause.

- Corporation tax

The corporation tax implications are outlined below. You should note that the legislation does not expressly cover remortgage transactions involving the transfer of a mortgage from one finance undertaking to another or portfolio transfer transactions involving two or more finance undertakings. Under the legislation, where an interest in a property is acquired by a finance undertaking from a third person (other than the customer) the new legislation only applies where the finance undertaking has acquired such interest jointly with the customer. One would therefore recommend prior revenue clearance for any transaction that involves the transfer of a mortgage (or a portfolio of mortgages) from one finance undertaking to another. It is expected that Irish Revenue would be helpful in sorting out any genuine problem.

Finance undertaking’s taxation Under either of the arrangements set out in diminishing musharaka and murabaha the finance undertaking should be treated as having made a loan to the customer. Accordingly, under a diminishing musharaka arrangement as set out above, the rent payable by the customer for using the property is to be treated as if it were interest arising on a loan made by the finance undertaking. Similarly, under a murabaha arrangement the incremental amount payable by the customer, i.e. the amount which is over and above the consideration paid by the finance undertaking for acquiring interest in the asset, should be treated for tax purposes as if it interested arising on a loan made by the finance undertaking. Whether such in- come is on trading account or otherwise will depend on the overall activities of the finance undertaking. Where a finance undertaking carries out the transaction as part of its trading activities, income from the transaction should be treated as arising on trading account. If so, then from a timing perspective the taxable income should be based on the accounting measure of income as computed un- der Irish / UK GAAP or IFRS.

Where the finance undertaking is obliged to make a charitable donation (for any additional payment received from the eventual owner) and such payment can be considered as a legitimate expense of entering into the diminishing musharaka or murabaha transaction, it is arguable that the expense should be treated no differently than any other expense incurred wholly and exclusively for the purposes of the trade of the finance undertaking or as an expense incurred in deriving non-trading income, where relevant.

Eventual owner’s taxation

On the basis that the rental or the incremental payments under 25.14 above are treated as interest for tax purposes, the customer (eventual owner) should be entitled to mortgage interest relief (where it is a principal private residence that would qualify for such relief under conventional financing arrangements).

The legislation specifically clarifies that:

- the finance undertaking is not entitled to claim industrial building allowances (tax depreciation on industrial building) on the cost of the property which is acquired by the finance undertaking for the purposes of entering into a Shari’a-compliant mortgage (credit transaction).,

- the borrower is to be treated as having acquired full interest in the property on the date of entering into a Shari’a-compliant mortgage (credit transaction). Accordingly, where entitled, the borrower may claim industrial building allowance (tax depreciation on industrial building) on full cost of the property from that date,

- the amount treated as interest is not to increase the tax basis of the property for the borrower. Accordingly, the amount treated as interest is to be ignored by the borrower in claiming industrial building allowance (tax depreciation on industrial building) or in calculating a capital gain or loss on a subsequent disposal of the property, and

- where the borrower disposes of its interest in the property to the finance undertaking and then immediately reacquires the interest from the finance undertaking, the disposal of interest by the borrower to the finance undertaking would not give rise to a balancing charge or a balancing allowance. The disposal of the interest by the borrower may potentially be subject to capital gains tax.

For Shari’a-compliant mortgage arrangements entered into between a finance undertaking and its employee(s), the legislation specifically provides that the transaction should be treated as if the employer has made a loan to the employee. Accordingly, the rules relating to preferential loan arrangements should apply, i.e., there could be tax implications if the return receivable by the employer from the employee is lower than interest arising at the benchmark rate (market rate as provided in Irish tax law).

- Indirect taxes

Vat

As the credit return is to be treated for VAT purposes

as interest arising on a loan, the Shari’a-compliant mortgage arrangements set out in 25. should be considered as a VAT-exempt financial service relating to negotiating, giving and management of credit. The rental arrangement between the finance undertaking and the customer (eventual owner) should be seen as part of the overall financing arrangement and not as a separate arrangement. Accordingly, VAT should not arise on the rental arrangement.

Stamp duty

There should be no Irish stamp duty costs if the property which is the subject of the transaction is located outside of Ireland.

In relation to a property located in Ireland, there are a number of stamp duty issues that could arise on structuring a mortgage in a Shari’a-compliant manner. The most significant is the duplication of stamp duty cost, as the arrangements outlined in 25.14 involve two transfers of title to the property (first to the finance undertaking and then from the finance undertaking to the eventual owner) and each of them could potentially be subject to stamp duty. A remortgage of a property could also be subject to additional stamp duty costs. Furthermore, the transfer of a portfolio of Shari’a-compliant mortgages by one finance undertaking to another could involve a transfer which would be subject to additional stamp duty costs.

In addition, the eventual owner’s entitlement to reliefs, such as first-time buyer’s relief, could potentially be restricted.

The lease agreement could also be subject to stamp duty.

Changes needed in the legislation

In order to address the above issues, amendments would need to be made to Irish stamp duty legislation. This would mainly involve the following:

- The second transfer (from the finance undertaking to the eventual owner) would need to be exempted from stamp duty provided the due amount of stamp duty in relation to the first leg of the transaction, i.e. the transfer to the finance undertaking, has been duly paid.

- It could be provided that no stamp duty charge shall apply if the person selling the property also enters into an arrangement with the finance undertaking which involves a reacquisition of the same property.

- The transfer of a Shari’a-compliant mortgage portfolio between finance undertakings could be specifically exempted from a stamp duty charge.

- In order to preserve stamp duty reliefs available to the eventual buyer, it needs to be provided that the eventual owner (and not the finance undertaking) shall be deemed as purchaser of the property for the purposes of determining the applicability of any exemption or relief from stamp duty.

An exemption from stamp duty can be provided on lease agreements entered into with a finance undertaking where the lessee has also entered into a contract with the finance undertaking which involves the acquisition of the entire interest of the finance undertaking over a term which does not exceed the term of the lease agreement.

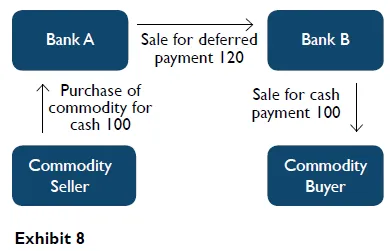

Inter-bank placement of funds

A Shari’a-compliant placement of funds between banks is typically structured under a murabaha arrangement. It would fall under the definition of a “credit transaction” under the legislation. It can be illustrated in Exhibit 8.

As set out in 25.13.1, on the basis that the transaction would involve goods that are capable of transfer by physical delivery, a charge to Irish stamp duty may not arise on the transaction. Where the transfer is made under an instrument, a charge to stamp duty could arise, depend- ing on the nature of instrument and the goods involved.

Inter-corporate lending

A Shari’a-compliant inter-corporate lending transaction also typically is structured under a murabaha arrangement. The structure is exactly as illustrated in 25.16 above except that two corporate entities enter into the arrangement instead of banks. This arrangement would also fall under the definition of a “credit transaction”.

Corporation tax

lending company’s taxation

The ‘mark-up’, being the difference between the cost and the sale price, should be treated as taxable income of the lending company. Whether such income is on trading account or otherwise would depend on the trading position of the lending company.

As can be noted from the above, Bank A is placing a deposit with Bank B. Typically, a commodity (say copper) is used and all the transactions are entered into almost at the same time. It is common for banks to enter into a master agreement which contains the common elements of the arrangement and governs all murabaha transactions that take place between the two banks going for- ward.

- Corporation tax

On the assumption that both the banks will enter into the above transaction as part of their normal trading activities, the tax treatment of the above arrangement should not be different from a conventional arrangement relating to the inter-bank placement of funds. The ‘mark-up’, being the difference between the cost and the sale price, should be treated as taxable income of the bank placing funds and a tax-deductible expense for the other bank. Also, from a timing perspective, the taxable trading profits of both the banks should be computed on the basis of the accounting measure of such profits computed under Irish / UK GAAP or IFRS.

- Indirect taxes

Vat

The VAT analysis should be the same as that outlined earlier. Being a financial service, the arrangement should be exempt from VAT.

Borrowing company’s taxation

For the borrowing company, the tax treatment would not be different from a conventional borrowing arrangement. The markup should be treated for tax purposes as if it were interest payable on a loan made by the finance undertaking to the borrower or on a security issued by the borrower to the finance undertaking, where appropriate.

On the basis that the “borrowing” is for the purposes of the trade of the borrowing company, the timing of the tax deduction would generally follow the accounting measure of the expense in the profit and loss ac- count computed in accordance with Irish GAAP or IFRS. However, where the borrower would have been entitled to claim interest as a charge relief if it were conventional finance, the tax deduction should be available when such “interest” is paid by the borrower, in line with the rules relating to interest as a charge relief.

- Indirect taxes

Vat

The VAT analysis should be the same as that outlined in 25.13.1. Being a financial service, the arrangement should be exempt from VAT.

Stamp duty

As set out in 25.13.1, on the basis that the transaction would involve goods that are capable of transfer by physical delivery, a stamp duty charge may not arise on the transaction. Where the transfer is made under an instrument, a charge to stamp duty could arise, depending on the nature of instrument and the goods involved.

Securitization

A sukuk arrangement is broadly similar to a conventional securitization arrangement. However, in compliance with Shari’a principles, the underlying asset has to be capable of transferring at a value other than book value and must be capable of some halal (permissible) use to produce income for the note holders. The scholars broadly agree that under Shari’a principles, cash and cash equivalents cannot be traded for a value other than par. Accordingly, tangible assets (such as property or machinery or plant) and financial assets (such as shares and securities) that principally draw their value from tangible assets are used in structuring sukuk transactions. The financial as- sets must entitle the owner to a proportionate beneficial interest in the underlying tangible assets.

Broadly, a sukuk SPV issues certificates known as sukuk (referred to as investment certificates in Finance Act 2010) to investors for cash which it uses to fund the purchase of an asset. The beneficial interest in the asset is transferred to the noteholders for cash consideration. The sukuk represents a proportionate share in the beneficial ownership of the underlying asset that has been the subject of the arrangement. The asset gives rise to income that is acceptable from a Shari’a perspective and that can be paid to the sukuk holders. The amount of income is generally not very different from what would be a return under a commercial bond issue in a securitization transaction. It is possible to structure a sukuk arrangement whereby a class of assets is involved instead of a specified asset or assets.

A typical sukuk arrangement is illustrated in Exhibit 9.

The new legislation applies to sukuk (investment certificates) that:

- have been issued by an Irish resident company which redeems them after a specified period of time, i.e. the term of the transaction,

- are issued to the public (including companies) in general. The reference to public is in general terms and does not require listing on a stock exchange,

- entitle the owner to share the profits and losses of the issuing company in proportion to the number and value of the certificates, and

- are treated partly or wholly as a financial liability of the issuer company in accordance with IFRS or Irish / UK GAAP.

sukuk arrangements would fall under the definition of “investment transactions” in the legislation.

- Ijara-based securitization arrangement

Fundamentally, the beneficial ownership of the assets (whether real assets or financial assets carrying an interest in the underlying real assets) is transferred by the originator company to a ‘special purpose vehicle’ (“SPV”). The SPV finances the purchase by issuing sukuk to investors. The interest in the underlying assets is then effectively leased by the SPV to the originator for periodic lease rentals that are received by the SPV for onward distribution to sukuk holders. The originator also undertakes to reacquire the interest of the SPV/sukuk holders in the underlying assets at an agreed price. The lease rental amounts economically equate to interest or return in a conventional securitization arrangement. On the expiry of the arrangement, the beneficial inter- est is transferred back to the originator company and the sukuk are redeemed by the SPV from the proceeds realized on transferring back the assets.

- Wakala based securitization arrangement

This is largely based on the same arrangement as set out for ijara-based securitization. However, instead of leasing its interest in the assets to the originator, the originator is appointed as agent for a fee and or a share in profits derived from the use of the asset. As agent, the originator uses the asset on behalf of the SPV. The SPV may also allow the agent to retain any amount of profit generated from use of the asset which is in excess of a specified threshold that would belong to the SPV. The share of income paid to the SPV is the economic substitution of interest or return under a conventional securitisation arrangement.

- Mudaraba or musharaka based securi- tisation arrangement

This arrangement is also largely based on the same arrangement as set out above for ijara and wakala based securitization. Under this approach, the SPV enters into a partnership arrangement with the originator whereby any profit arising from the use of the asset is shared between the borrower and the SPV. Generally, the SPV’s share of profit would be an amount which would economically be very similar to interest on a bond or return under a conventional securitization arrangement.

- Corporation tax

On the basis that the amount of investment return does not exceed an amount which would be interested arising on a conventional investment of a similar nature, the amount of investment return should be treated for tax purposes as if it interested arising on a security. If the amount of investment return exceeds the amount of what would be interested on a comparable conventional investment, the key implications are discussed in more detail below along with discussion on the taxation of the sukuk issuing SPV.

The securitization regime outlined in Irish tax law applies only where the securitization SPV owns financial assets. Accordingly, where the originator transfers financial assets (such as shares of companies whose business is in compliance with Shari’a principles), the Irish securitization regime should be applicable to a Shari’a-compliant securitization SPV. Where the originator transfers real assets to the sukuk SPV, the Irish securitization regime will not apply.

The new Irish legislation relating to Islamic finance transactions specifically confirms that for tax purposes the sukuk holders (certificate owners) are not to be treated as having a direct legal or beneficial interest in the assets held by the sukuk issuing SPV. Consequently, the sukuk holders are not entitled to claim any capital allowances or industrial building allowance (tax depreciation) in respect of the assets held by the sukuk issuing SPV. Moreover, any income, profits, gains or losses arising from or attributable to the assets are treated for tax purposes as if such income, profits, gains or losses have accrued to the sukuk issuing SPV and not to the sukuk holders.

24.18.5 Taxation of sukuk holders

The taxation of investment returns for sukuk holders is summarised below.

- Where a sukuk holder, who has acquired the sukuk directly from the issuing company (“the original sukuk holder”), receives any return from the sukuk issuing SPV, such return is treated as an investment return for the original sukuk holder.

- Where the original sukuk holder redeems the sukuk, the gain or loss on such redemption is treated as the investment return. It should be noted that where the original sukuk holder disposes of the sukuk in the secondary market, the gain or loss on such disposal is not considered as the investment return. Instead, such gain or loss is treated under normal tax rules and a distinction is made between the capital and revenue nature of the gain depending on facts and circumstances of the case.

- Where a person who has acquired sukuk from the secondary market (“the subsequent owner”) receives any return from the issuing company, such return is treated as an investment return.

- Where a subsequent owner redeems the sukuk, the investment return on such redemption is calculated by comparing: (a) the disposal proceeds received by the subsequent owner, with (b) the amount received by the sukuk issuing SPV from the original sukuk holder. The balance of the gain or loss arising to the subsequent owner (being the difference between the redemption proceeds and the acquisition value of the sukuk) would have to be treated under normal tax rules and a distinction made between the capital and revenue nature of the gain de- pending on the facts and circumstances of the case.

Where part of the return is considered as a distribution, the tax analysis may be different to that outlined above.

Taxation of sukuk issuing SPV

The sukuk issuer SPV is entitled to a tax deduction in respect of the investment return paid to sukuk holders unless it is considered a distribution (being in excess of what would be interest under a comparable conventional arrangement). As mentioned in 25.10.1, interest can be reclassified as a distribution where it is, to any extent, dependent on the results of the company. However, Irish Revenue have issued additional guidance clarifying that investment return will not be re-classed as distribution solely by virtue of the profit-participating nature of the arrangement where the expected return on the transaction is determined at the time of entering into the transaction and is equivalent to an interest return on a comparable conventional arrangement. Where the sukuk is issued by a qualifying Irish securitization vehicle, the reclassification should not apply in any event solely by virtue of the profit-participating nature of the instrument, as is the position in the case of qualifying Irish securitization vehicles.

Indirect taxes

Vat

The normal Irish VAT provisions applicable to conventional securitization arrangements should apply on the securitization (sukuk) arrangement.

Stamp duty No Irish stamp duty should apply to the issue, transfer or redemption of sukuk (investment certificates). The normal provisions of SDCA would apply in respect of assets acquired or disposed of by the sukuk issuing SPV. For example, a charge to Irish stamp duty may not arise on the transfer of the asset are located outside of Ireland.