Oh, East is East and West is West, and never the twain shall meet, Till Earth and Sky stand presently at God’s great Judgment Seat; But there is neither East nor West, Border, nor Breed, nor Birth, When two strong men stand face to face, tho’ they come from the ends of the earth!

Introduction

Rudyard Kipling’s poem, A Ballad of East and West (1895), is sometimes mistakenly cited as an example of irreconcilable differences between two worlds. Indeed, if one reads only the opening line of the oft-repeated verse quoted above, it is easy to see how the misunderstanding can occur. The reality is rather different as in this verse Kipling is in fact discussing egalitarianism and reconciliation. This is perhaps a good metaphor for describing the DFSA approach to the regulation of Islamic finance as it has sought to create a level playing field able to combine conventional finance with Islamic finance as well as introducing a flexible Islamic finance regime accommodating both liberal and conservative scholarly opinions.

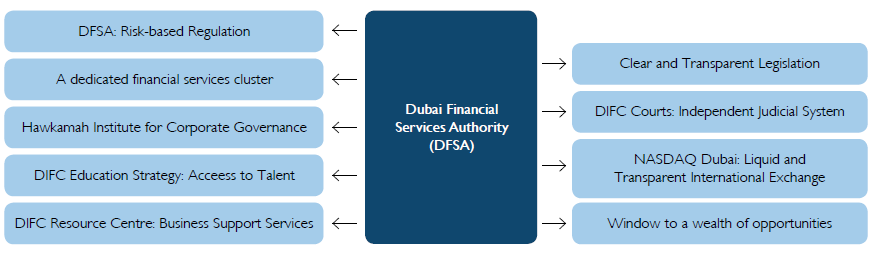

A core element of any financial services market is the authority of its legal and regulatory environment. With the recent global financial crisis leading towards greater convergence and dialogue amongst regulators, the approach of the DFSA towards both conventional and Islamic finance markets has always been to adopt a pragmatic approach to the development of the DIFC as a new capital market.

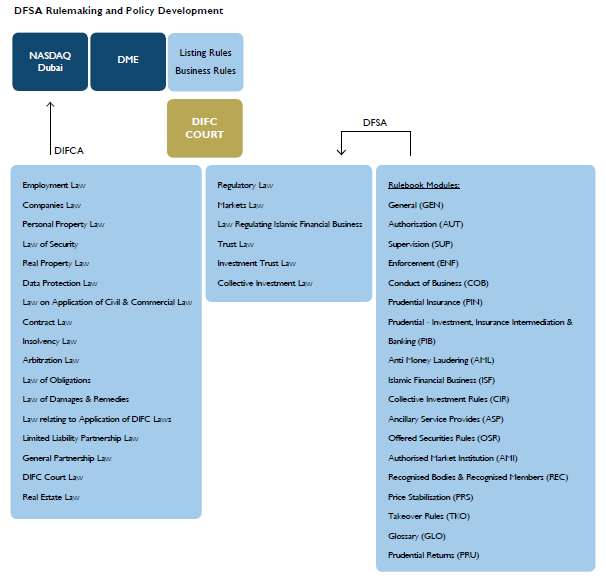

The DIFC is an onshore financial free zone in the Emirate of Dubai, part of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), with no local partner requirements. Comprising 110 acres, the DIFC has its own legal and regulatory system, based on English common law, including having its own civil and commercial courts, and its own financial services regulator, the DFSA. The character of the Centre is international and, largely, a wholesale one, although retail business is allowed. This means that most customers of DIFC firms will be either other businesses or professionals and high-net-worth individuals. Some issues concerning the retail market will therefore be less important for us; for example, it is difficult to see the DIFC becoming a centre for Islamic microfinance. On the other hand, as an international onshore centre, it has businesses from many countries operating within. DIFC offers these businesses an international framework through which they are regulated and is not tailored to the needs of a specific national market. The federal law under which the DIFC is established provides that within the Centre the normal civil and commercial laws of the UAE do not apply. That means that the DIFC has had to create its own legal regime (including, for example, Companies Law, Data Protection Law and Employment Law), and of course its own laws and rules for financial services. The significance of this is that they have created an idiosyncratic approach to regulating Islamic finance using a blank sheet of paper. This has given the DIFC an advantage in creating a regime that welcomes all types of Shari’a interpretation – be it liberal or conservative.

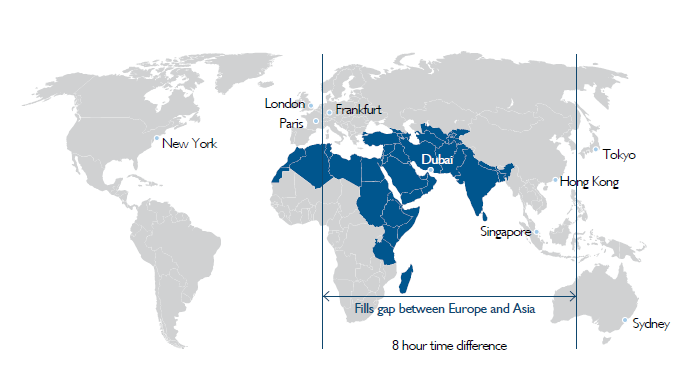

Crossroads between East and West

Dubai sits in the enviable position of spanning Eastern and Western time zones and the DIFC has been engineered to fill the gap between Europe and Asia–not just for the benefit of time zones but also the cultural and practical benefits of acting as a bridge between conventional finance and Islamic finance, as well as bridging the divisions that exist amongst different scholarly opinions within Islamic finance. Its range and scope extends far beyond its 110 physical acres and this is one of its core attractions as an emerging centre for Islamic finance.

The three pillars of the DIFC

The DIFC has three core parts – the DIFC Authority which provides overall direction for the development and marketing of the DIFC. The DIFC Courts which offer the DIFC’s its own civil and commercial court system – effectively making the DIFC a quasi “state” within a state, albeit still subject to the criminal law of the UAE and lacking any form of sovereignty. And finally there is the DFSA.

As an integrated regulator, the DFSA regime is based on international best practice and is applied uniformly across all firms, including Islamic firms, using a risk-based approach. There is no scope for regulatory arbitrage be- tween conventional and Islamic firms in the DIFC. As a risk-based regulator, the DFSA focuses on the specific risk posed by the firm. Consequently laws, rules and supervisory practices are forumulated to take consideration of the actual risks posed by the business in question. A corollary of this is that similar risks should be treated the same. So where the risks in Islamic and conventional finance really are similar, then the same rules should apply. But of course a regulator needs substantial knowledge of Islamic finance to know when the risks are similar, and where they are subtly different. The DFSA have had to modify the integrated, international standards in order to reflect the specifics of Islamic finance which are not ordinarily accommodated within international standards. Underpinning all this is the DFSA Shari’a systems philosophy, whereby it prescribes the obligation for a firm to have systems and controls in place to ensure that the business is operating in accordance with Shari’a.

Significant features

Turning to the significant features of the regulatory regime, the DFSA is an independent integrated regulatory authority based on the UK’s FSA model. It has statutory authority with guaranteed operational independence and funding. Its regulatory approach is based on international standards, best practices and the laws of the world’s leading financial jurisdictions. The DFSA has modeled their regime using the principles and standards of the following sources – IOSCO, Basel, IAIS (DFSA hosted the IAIS annual conference and triennial meeting in 2010), FATF and from an Islamic perspective the standards of the AAOIFI and the IFSB. Active members of both bodies sit on various DFSA committees, inform- ing opinion and helping to shape the standards as well as to implement them. But business models in Islamic finance continue to evolve rapidly, with new standards being created year by year. There are still important gaps which need to be filled.

Level-playing field

Our DFSA’s cross-sectoral approach to regulation has many benefits and is key to its practical approach to Islamic financial services regulation. The cornerstone of the regime is risk-focused. They have intentionally sought to create a level playing field by applying the same set of regulations, subject to due modification, to all authorized firms regulated in the DIFC, irrespective of whether or not they are conventional firms, Islamic firms or conventional firms housing Islamic windows. 11% of the total population of firms are Islamic of which 5% are full-fledged Islamic firms and 6% are Islamic windows. The DFSA have the advantage of not having to modify legislation, or ‘bolt on’ Islamic finance to an established conventional financial system. This structure provides a sound basis to address the specific features of capital markets regulation, including Shari’a-compli- ant capital markets products.

Fundamental approach

One challenge which is often associated with Islamic finance, is the lack of standardization. This is a consequence of inconsistencies in respect of laws and regulations of the market within which Islamic finance operates and the issues which may arise as a result of the incorporation of Islamic and conventional finance into the same capital market framework. There is also the ongoing issue of the lack of commonality of Shari’a contracts and rulings. Indeed, it is this very inconsistency that has led DFSA to adopt a Shari’a systems’ based approach to the regulation of Islamic finance, using a facilitative regulatory framework. This has been achieved by creating clearly defined, international regulatory parameters within the DIFC which is conducive not only to the cross-sectoral features of Islamic finance, but the pace of innovation in this industry.

The DFSA’s pragmatic approach in respect of regulating Islamic finance is to provide an integrated regulatory framework with due modification to reflect the specifics of Islamic finance. Fundamental decisions were made early on to allow a great deal of flexibility. There are specific categories covering both pure Islamic firms – acknowledging this defined market, as well as Islamic windows. Contract forms that must be used for particular types of transaction are not prescribed by the DFSA. However, the regime is flexible enough to allow the use of Islamic windows – effectively providing conventional financial houses with the flexibility of combining the best of both worlds – perhaps the best example of east meeting west.

Shari’a governance

The most important decision was on Shari’a governance. Although there are regulators in some countries who believe they should play no part in anything with a religious dimension, when a firm or product claims to be Islamic, that is a very significant claim it makes to its customers. Other regulators make themselves the arbiters of Shari’a matters, typically by establishing their own Shari’a Council as the effective authority within their area of responsibility. That has the advantage of securing uniform interpretation locally, but in a world where there is no overall consensus – and if there were, a Shari’a Council would probably not be necessary – it does risk solidifying divisions along national lines.

Shari’a systems regulator

In a centre where both firms and customers are international, DFSA decided to be a Shari’a systems regulator. This means that any firm that claims to be Islamic must have a SSB made up of competent scholars. It must have systems and controls to implement the SSB’s rulings and must have annual Shari’a reviews and audits, following AAOIFI standards. It must also disclose details of its SSB to its customers, allowing them to make their own decisions about the reliance they are prepared to place on its rulings. As an active regulator whose staff are well-experienced in evaluating systems and controls, DFSA supervises to ensure that these arrangements are working in practice as well as on paper.

We believe, incidentally, that this is a model well-suited to many Muslim-minority jurisdictions, where regulators would balk at arbitrating on religious matters, because it places the onus of compliance on the firm, and transforms the problem into one of systems and controls.

prudential requirements

The next question that needed to be considered was the prudential regime for Islamic firms, particularly how much capital they need to hold. For Islamic banks, standards were drafted utilizing those of the IFSB. In particular, the DFSA pay close attention to the concepts of Displaced Commercial Risk (DCR) for Profit Sharing Investment Accounts (PSIAs) In principle, PSIAs are investment accounts, in which the investors bear risk to both principal and return. In practice, they are often offered as an alternative to a conventional interest-bearing deposit account, and it is not always clear that bank customers understand the risks to which in principle they are exposed. Even if they do, many PSIAs share the basic problem of banking: maturity transformation. Fundamentally, the customers can withdraw their money faster than the bank can recover its loans or realize its investments. This creates pressure on the bank to maintain returns at market-competitive rates, even where it is not obliged to do so – so-called Displaced Commercial Risk (DCR).

The IFSB standards this through a variable parameter (ά), which allows regulators to set a capital requirement for PSIAs at any level up to that which would be applicable to deposits, and on a similar basis of calculation. DFSA sets ά at 35%, reflecting the relatively sophisticated market previously mentioned. IFSB standards have been used to give guidance on the treatment of Islamic instruments, even where they are held by conventional firms.

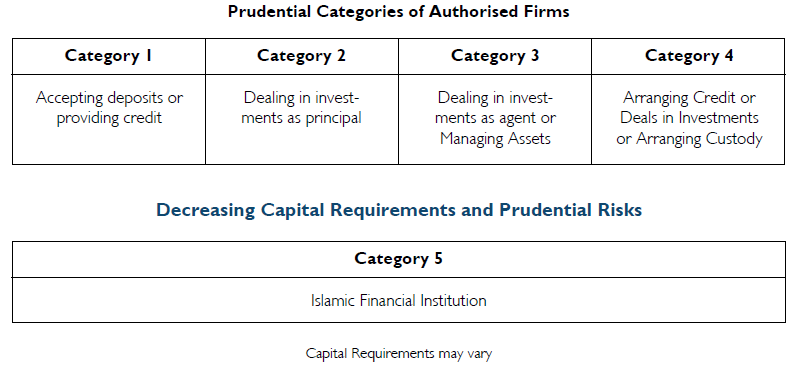

The DFSA supervises five prudential categories of Authorized Firm, which are shown in the diagram be- low. Category 5 represents Islamic financial institutions which are banks managing PSIAs; however, the regime is flexible enough to allow firms to carry on categories of financial activity elsewhere so long as they have the permission to do so either exclusively as an Islamic financial institution, or as an Islamic window, which will appear as an endorsement on the firm’s license (nb: category 1 will allow an Islamic window, but an exclusively Islamic bank managing a PSIA must seek a Category 5 License).

takaful

For takaful, although the DFSA included provisions on the treatment of Islamic instruments and zakat, when it drafted its regime no international standards were available. At that time, the business models of takaful companies had not yet settled into a clear pattern. However, the DFSA have extensive powers to waive or modify its own rules in particular cases, and have used them to recognise properly the typical structure of a modern takaful company, which involves one or more pools of money which are considered to belong to policyholders within a shareholder company. In this area, the IFSB has issued a draft standard. This is aligned with the standards for conventional insurance which are emerging from the IAIS.

Disclosure

The DFSA requires the same degree of disclosure for Islamic transactions as required for conventional products. Transparency and disclosure is an obligation on all authorized firms. This means that a firm must provide details of the Shari’a Supervisory Board (SSB) as well as details of any subsequent changes to the board that has undertaken the Shari’a review. In addition, a copy of their annual report must be provided to the board of the Authorized Firm which is duty-bound to pass this onto the DFSA. It is also vital that any appropriate disclosures are made vis-à-vis AAOIFI standards.

The DFSA have also implemented a set of disclosures specific to Islamic finance, in addition to those about the SSB. For example, a takaful company has to disclose the basis on which any surplus in the takaful fund will be shared: a bank managing a PSIA must disclose how profit is allocated between the bank and the client. Again, these disclosures largely follow standards from the IFSB and AAOIFI. There are also specific rules for Islamic funds and for sukuk. In both cases these are reasonably straightforward, and relate mainly to Shari’s governance. In the context of sukuk, the DFSA regime prescribes regulations for the offer of sukuks; and holding sukuks as investments. In this case the prudential requirements, which are based on international standards, but duly modified for Islamic finance, will apply, including the specific risk weights prescribed for sukuks. In respect to the offer of securities, including sukuk, it is an activity to which the Markets Law 2004 and Offered Securities Module apply. For the offer of Islamic securities, the DFSA requires the following initial and ongoing disclosures to be made:

- details of the SSB that has undertaken the Shari’a review for the offer;

- the opinion of the SSB as to whether the offer is Shari’a-compliant;

- description of the underlying structure of the transaction;

- any applicable disclosures prescribed by AAOIFI Shari’a Standards;

- financial accounts be audited in accordance with

AAOIFI or other acceptable standards

– any subsequent changes to the SSB

These requirements are found in Islamic Finance Rules, which apply to any person making an offer of securities held out as Islamic or Shari’a-compliant. There are specific requirements in the Listing Rules of NASDAQ Dubai which also apply to all types of securities that are held out as being Shari’a-compliant.

Recent rule book enhancements

The DFSA have recently restructured the rulebook to group more of the material relating to Islamic finance in one place, and have also, through its website, made available tailored Islamic finance handbooks so that firms undertaking Islamic finance business in a number of areas can quickly see all the rules that apply to them. They have made significant changes to the funds regime introducing a new type of fund, exempt funds, which can be either conventional or Islamic. Such fund structures lend themselves well to hedge funds and private equity funds. One important innovation for such funds is lifting the AAOIFI requirement to have three scholars on an SSB. Given that the fund manager would in any case have to have its own SSB of three scholars, the DFSA decided that a firm would be al- lowed to have single scholar for an exempt fund, given that such funds are designed only for ultra-high net worth and sophisticated investors rather than retail. It was reasoned that given the scarcity of scholars, this was a pragmatic approach to take.

Mutual recognition

In 2008 the DFSA signed a mutual recognition agreement for Islamic funds with the Malaysian Securities Commission, which allows domiciled Islamic funds both in Malaysia and the DIFC to be marketed and sold in each jurisdiction. They now have 53 bilateral Memoranda of Understanding with other international regulators – the more agreement there can be between regulators then the greater prospects for growth can take place.

Future regulatory challenges

For the future, there are a number of challenges for regulators. One will be to keep up with the development of standards, both conventional and Islamic. The financial crisis has spurred the development of new standards in conventional finance, and Islamic finance will need to respond. To give just one example among many, the Basel Committee is consulting on new standards on liquidity and stress testing. Regulators of Islamic finance will need to consider their response, and in fact the IFSB is working on standards of its own. But standards are no use unless they are implemented, and we are also seeing new international pressure for standards implementation. So any regulator will have a sustained challenge to implement new standards. In Islamic finance, the challenge will be greater because of the relative novelty and complexity of this area.

Second, regulators will need to keep up with the continuing rapid development of the business itself. New models and structures are constantly being proposed and tested in the market, and it is unclear which of them will survive. For example, the range of possible sukuk structures is enormous and their economic characteristics, and hence the regulatory risks are not necessarily specified by the principal contract involved. For example, it is possible to have a mudaraba sukuk which, economically, looks similar to a conventional debt instrument, or one which looks like a collective investment fund, or one which looks like an equity. Although in practice, most sukuk have been structured to resemble debt instruments, it is possible that future sukuk will have more elements of genuine asset, rather than counterparty risk and so need for different market disclosures. In another area, there is a constant search for short-term liquidity management instruments not based on commodity murabaha, and should a new structure become an industry standard, regulators will need to consider what risks it poses.

Third, as the whole industry grows, it faces the challenge on how to deliver Shari’a governance. There are at least two sets of issues here. One is that in an industry with more firms, and larger firms, a governance regime in which an SSB has to sign off on each new structure, transaction or product implies a requirement for more scholars, while the training and development of new scholars itself is a long process. The second, related set of issues is that the existing governance and review standards were drafted with mainly Islamic banks in mind. But the industry now has a wide variety of firms and for the intermediary sector – brokers, advisers, etc – which is generally characterized by smaller firm sizes, the full burden of the standard Shari’a governance structures may impose transaction costs which inhibit the ability to compete with the conventional industry, and which may not be justified by the volume and complexity of the Shari’a decisions that need to be made. Most likely, these problems will not be solved by one method alone. We are already seeing changes in the Shari’a advisory industry, whose effect is both to shift some of the burden away from the most senior scholars and to provide a better development path for new scholars. Another means is the development of industry standards to reduce the need for individual transaction approvals. Standard documentation structures are one example, but standard Shari’a screens for equity investments are another. A third may be the development of new governance standards and the DFSA are actively working with AAOIFI on this issue. Regulators will have their part to play in these developments, which will be essential if the industry is to grow at anything like its recent speed. Islamic finance continues to evolve and its ability to adapt and innovate will continue to drive the need for a practical response from regulators. The DFSA believes that its facilitative infrastructure and its use of Islamic windows to bridge the gap between the conventional and the Islamic provides a helpful and flexible approach to the regulation of this growing industry. The DIFC has some unique advantages as a centre for Islamic finance, spanning as it does both east and west.