A Real Innovation Or An Example Of Misconception Of An Economic Need-professor Humayon Dar

INTRODUCTION

Salam is a quasi-forward sale contract that allows trading parties to a transaction to defer delivery of merchandise to a future date. The price of the merchandise is paid upfront. A strict condition of validity of salam is that it should be used for trading in unspecified but specific1 homogenous commodities or items. There is almost a consensus of Muslim jurists that salam cannot be used to trade in currencies, for which a specific set of rules is relevant, called ahkam al-sarf. In fact, the first Shari’a Standard issued by Accounting & Auditing Organisation for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) deals with trading in currencies, which specifically prohibits trading in commodities in such a way that counter-values (one or both) are deferred. Similarly, AAOIFI Shari’a Standard No. 10 clearly prohibits the use of salam for trading in currencies2.

There is a minority of scholars in the Indian sub-continent (and elsewhere), who opine that paper currency should not be considered like commodity-based money, and hence is an imperfect substitute of the classical money in the Islamic history, i.e., gold and silver coins. According to this view, even if paper currency is not considered as commodity, modern money should be considered as a new medium of exchange for which trading rules may be different from what are prescribed under ahkam al-sarf. However, this view is refuted by vast majority of jurists from all over the Muslim world.

The question arises if currencies as used in all countries of the world (i.e., as money with principal use as medium of exchange) should be considered as commodities, and if they are perfect or imperfect substitute of the money in the form of gold and silver coins. There are some parallels to this debate in the old juristic writings wherein non-precious metal coins, called fuloos in Arabic, have been compared with the gold and silver coins.

HISTORICAL JURISTIC TREATMENT OF CURRENCIES

There is a plethora of literature on the juristic treatment of later currencies (non-precious metallic coins called fuloos) and modern paper-based currencies. There is growing interest in digital currencies but a globally accepted juristic view on it has yet to emerge.

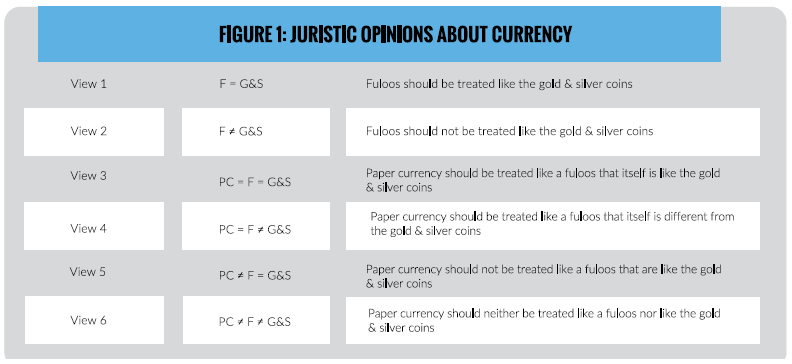

The juristic opinions can be divided into six groups:

- Later currencies, i.e., fuloos should be treated like the gold and silver coins;

- Later currencies, i.e., fuloos should not be treated like the gold and silver coins;

- Paper currencies should be treated like fuloos, and hence should be treated like the gold and silver coins;

- Paper currencies should be treated like fuloos, and hence should not be treated like gold and silver coins;

- Paper currency should not be treated like fuloos but it should be treated like the gold and silver coins; and

- Paper currency is neither like fuloos nor like the gold and silver coins.

CURRENCIES VERSUS MONEY

In economic literature, a more generic term is preferred over currencies, i.e., money, which ideally should serve as a medium of exchange, store of value, unit of account and standard for deferred payments. All currencies are different forms of money, although it is not true conversely.

Ahkam al-sarf should apply to anything that serves basic functions of money. Singling out paper currency as a special case and, hence, allowing salam or deferred payment sales in it will open a Pandora’s Box, which will defeat the whole purpose of developing a new system based on the prohibition of interest.

Ahkam al-sarf should apply to anything that serves basic functions of money. Singling out paper currency as a special case and hence, allowing salam or deferred payment sales in it will open a Pandora’s Box, which will defeat the whole purpose of developing a new system based on the prohibition of interest.

The safest bet would be not to create any distinction based on the form, i.e., gold and silver coins, other metallic coins, paper currency or digital forms of money, but to rather consider anything that fulfils the functions of money, subject to ahkam al-sarf.

AN ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF SALAM

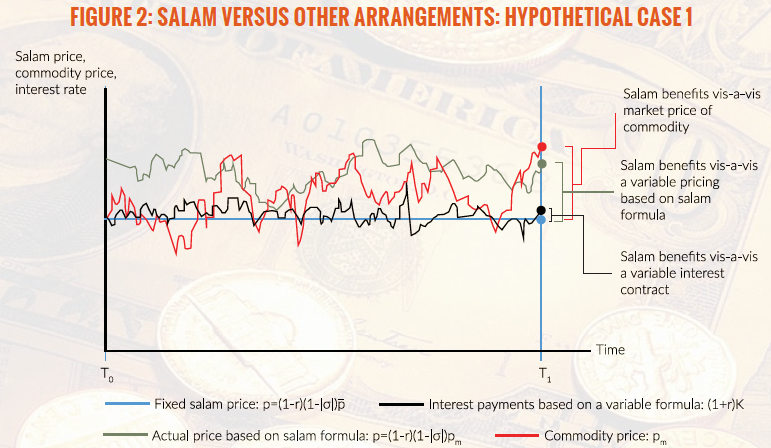

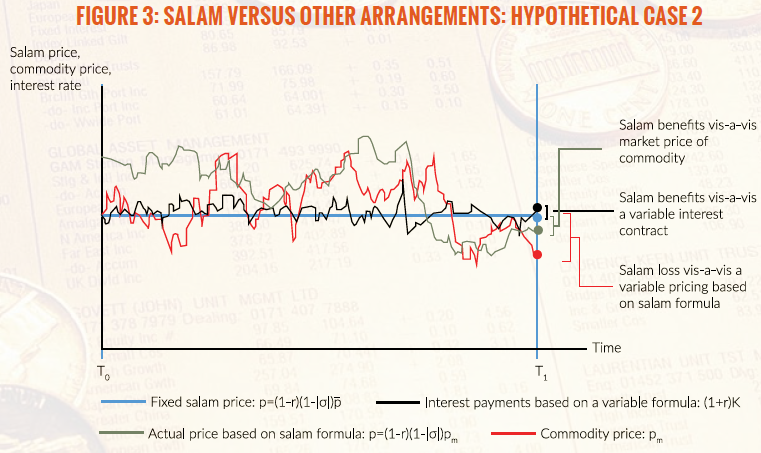

Salam can be seen as a tool to access finance from the viewpoint of the seller, and a hedging instrument for the buyer. The buyer and seller must agree on a price that maximizes financial benefits to the seller and hedging benefits to the buyer. Therefore, the price determination must be left to the trading parties, and must not be determined exogenously. A rule of thumb for price determination on part of the buyer is to agree on a price equivalent to p=(1-|σ|) p-μ; where σ is the standard deviation of the price; p is the average market price over a certain time period, t; and μ is the bargaining factor. The finance-seeking seller will agree on a price that is no more than (1 + r)p; where r is cost of borrowing from financial markets. In a perfectly competitive market, μ=r(1-|σ|) p, giving rise to an agreed salam price, p=(1-r)(1-|σ|) p. If μ>r(1-|σ|) p, then salam as a financing tool will be more expensive than an interest-based alternative available in the financial markets. The salam price in this case will have a premium more than the interest rate prevailing in the financial market. μ-r(1-|σ|) p>0 may be construed as Shari’a premium.

The above salam price formula suggests that a true salam transaction will expose the buyer to any benchmarked rate of interest as well as the risk of commodity price fluctuations. Any other formula for price determination in case of salam (in which commodity price does not feature) may in fact give rise to a pseudo-salam contract.

Figure 2 compares a salam contract with financing based on variable interest rate5 (black line), purchase of commodity for a price on a future date at the time of delivery of salam commodity (red line), and a futures contract based on the variable rate pricing formula (green line). This is of course a hypothetical representation of the performance of a salam contract vis-à-vis market changes. In this particular case, a salam contract performs better than the alternatives depicted in the Figure.

Figure 3 presents a scenario where a salam contract incurs loss on the buyer, as the market price of the commodity is less at the time of delivery, as compared with the salam price. The salam contract may also perform less favourably as compared to a futures contract with actual delivery.

This kind of economic implications of the views of jurists must be taken into account in a meaningful eco-juristic analysis. Failing to do so may result in acceptance and application of some of the contemporary juristic views in product development, which may prove to be irreversible even if they happen to be erroneous.

SALAM IN CURRENCIES

Salam in currencies implies sale of a given currency (say British pound, £) for another currency (say US dollar, $) whereby the sellers of currency are allowed to deliver the currency on a future date. For example, if a Party A sells £100 (the subject matter) for a price of $150 to another Party B, then A must receive $150 now to deliver £100 in future. This type of salam in currencies is not permissible, in accordance with the majority view.

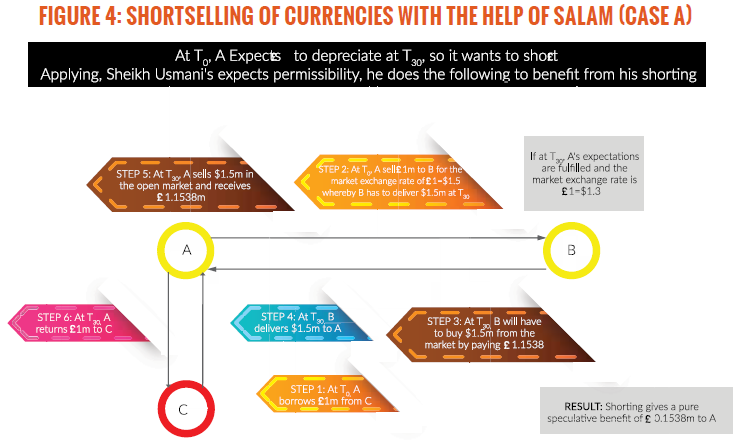

However, Sheikh Taqi Usmani, a prominent Pakistani jurist, permits sale of one currency for another one such that the sold currency can be deferred in delivery if the spot market price is paid upfront. This is an interesting exception that merits an economic analysis.

It seems as if Sheikh Usmani allows salam in currencies on the pretext that it serves a purpose for hedging against fluctuations in the price of the currency to which a party may have exposure in the future. He believes that this purpose may safely be achieved by allowing salam in currency conditional upon the salam price to be strictly the market price prevailing at the time of entering into salam.

This, however, is a flawed assumption, as spot sale and purchase of currencies serves the purpose of hedging better than the proposed salam (see below for further details).

THE ISSUE OF DIAGONALITY IN TRADING IN CURRENCIES

If we accept Sheikh Usmani’s view on the salam in currencies, then there is merit in exploring if a deferred payment sale in currencies is also allowed. Following Sheikh Usmani’s relaxation for salam in currencies, one may argue that it should be acceptable to defer price (in terms of one currency) for the purchase of another currency, provided that the agreed price in the sale is the prevailing market price, and not any other mutually agreed price between the transacting parties.

Trading in currencies is different from trading in commodities and other items that are not used as a medium of exchange. Perhaps this is why there are different rules prescribed in Islamic jurisprudence for trading in currencies. One important aspect of trading in currencies is that it does not matter whether one currency is a price or subject matter of sale. This is called diagonality in trading in currencies. For example, if a person A wants to sell US dollars (US, $) for GBP (GB, £) to a person B, the trade can be executed by a sale of $ from A to B who pays £. Alternatively, the trade can be executed by a sale of £ from B to A who pays $. The end result is the same. This diagonality does not exist in case of sale of a commodity for money. For example, if A wants to sell wheat to B for cash, the trade can only be executed by way of sale of wheat (as a subject matter) for a price denominated in a currency ($, £, etc.). It makes little sense to execute such a sale whereby $ or £ is subject matter of sale and wheat is the price.

THE RATIONALE BEHIND SHEIKH USMANI’S PERMISSIBILITY OF DEFERMENT OF ONE COUNTER-VALUE IN TRADE IN CURRENCIES

Sheikh Usmani seems to permit the so-called currency salam on the grounds that it allows the buyer to lock-in the exchange rate and hence hedge their position against exchange rate fluctuations. As stated above, this is not a valid rationale for permissibility of currency salam. A spot trade in currencies may in fact be superior to the disputed currency salam, as it is more flexible and more in favour of the hedging party. In the currency salam, the buyer pays $ upfront to receive £ in future, as per the prevailing market exchange rate at the start of the salam period. The buyer in fact ends up foregoing the use of £ during the salam period before £ is actually delivered. In case of a spot trade, the buyer will have the £ in hand to use it as and when it makes sense, or keep on using it as a hedge for its future foreign exchange obligations.

The permissibility of currency salam should be deliberated very carefully, as it may give rise to the structures that may change the whole view of ahkam al-sarf. One example is given in the following, which shows how currency salam can be used to structure short selling in currencies.

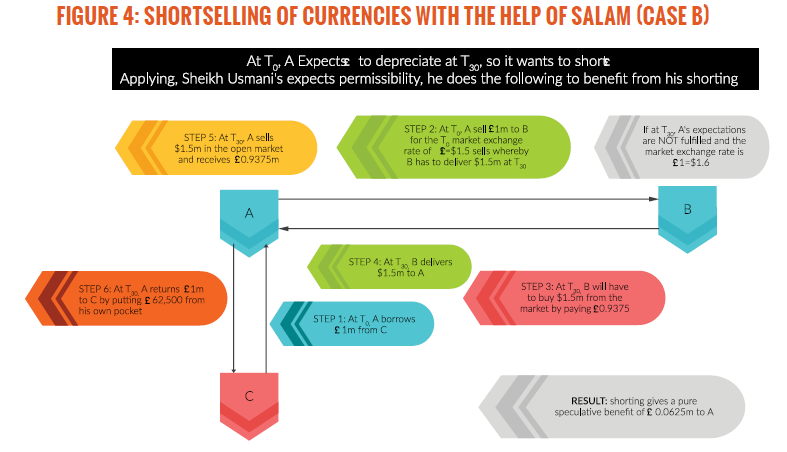

Figure 4 presents the case where short-selling works in favour of the speculator; while Figure 5 is a case where a speculator’s expectations are not fulfilled, and hence incurring loss for them.

The products based on currency salam already have shown divergence from the exceptional permissibility and the conditions attached. For example, the condition that only current market exchange rate should be used as price for salam in currencies seems to be violated by the currency salam product offered by Islamic banks in Pakistan. The salam price in this product is not based on the current market exchange; rather it is a mutually agreed price between the two parties. In this sense, it is a standard salam contract (impermissible according to the majority view, and in violation of Sheikh Usmani’s condition for permissibility).

Many Islamic banks use currency salam as a tool for providing liquidity to their customers. It is certainly not used as a hedging tool, as prescribed by Sheikh Usmani, and it seems as if it does not use the current market price as the salam price.

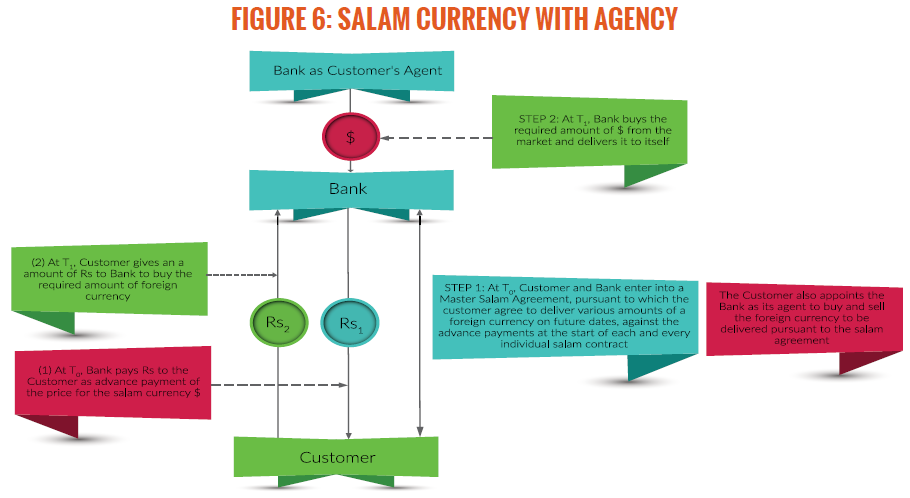

This is how the product works:

Step 1: A customer undertakes to supply a certain amount of a specific foreign currency (say, $) to the bank on a specific future date in exchange of local currency (Pakistan rupee, Rs) to be paid by the buyer (the bank) as advance price.

Important Considerations:

- The exchange rate is not exactly the prevailing spot market rate (i.e., the salam price is not strictly the prevailing market price).

- The customer may appoint the bank as its agent to buy the currency on its (customer’s) behalf from the market at the then prevailing exchange rate, and then deliver it to the bank.

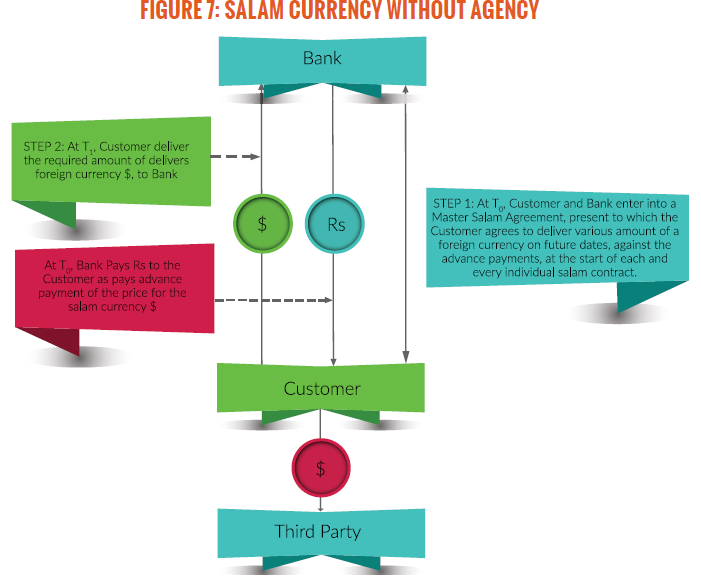

- Alternatively, the customer must arrange for the foreign currency from whatever sources to deliver it to the bank on the agreed date.

Step 2: One a future date of delivery, the bank, pursuant to B above and serving as the agent of the customer, buys the specific amount of $ from the market, and delivers it to itself on behalf of the customer.

Important Considerations:

- The customer must pay the bank an amount in Rs required to purchase the agreed amount of foreign currency that must be delivered to the bank pursuant to the salam sale.

- If the customer was expecting foreign exchange pursuant to an export bill, they will be able to deliver the required amount of the foreign currency, as per the salam agreement.

The transaction flow is shown in Figures 6 and 7. The former is an example of the use of agency in the structure, and the latter is a straightforward structure, without agency.

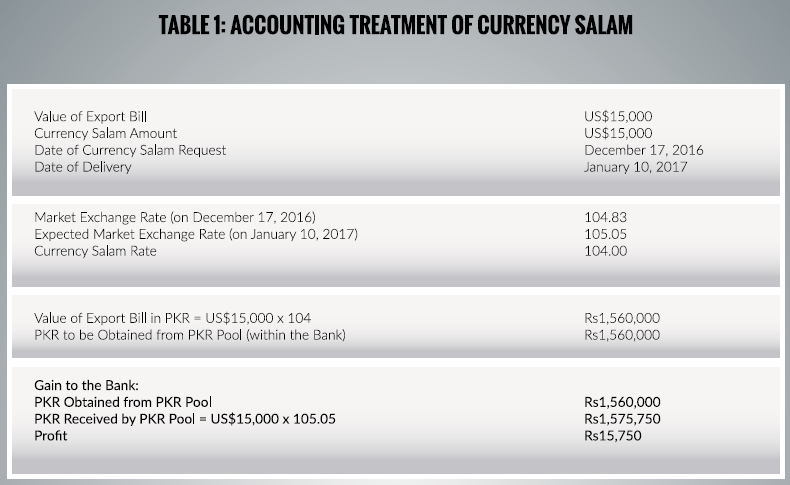

To further explain the above structure, accounting treatment of a currency salam transaction as employed by Islamic banks in Pakistan should be used. This is provided in Table 1

CONCLUSION

Currency salam may not be as straightforward from a juristic and economic viewpoint. It has huge implications for the way Islamic banking and finance is being practiced and the future direction it may take in wake of the permissibility of salam in currencies. As globally accepted Shari’a standards exist on salam, it is advisable to strict to them, instead of attempting to exercise Islamic financial engineering based on the views of some individual Shari’a scholars, even if they happen to be among the greatest jurists of the present time.