Hussain Kureshi

WHERE DO WE DRAW THE LINE OF ACCOUNTABILITY?

Modern corporations are complex beasts. They are owned by one or several entities and managed by others. From the perspective of a simple-minded Muslim, any legal corporate or governance structure that separates an owner of a company from the legal responsibility of the company’s actions may very well be unlawful. Conforming to this viewpoint, one may wonder if the traditional “shirka” was a legal entity in its own right. Nevertheless, in the modern world a private limited firm, a public unlisted firm and a pubic listed firm all are legal entities in themselves capable of employing resources, transacting and above all breaking laws and influencing the process of law-making.

Such firms are not “run” by their “owners” but by managers who have a “fiduciary duty” to their “owners” to act in the interests of the “owners”. So when something goes wrong, it is hard to blame anyone, employees or owners. Now coming to the question of owners, a private limited firm has a handful of“owners”, people who contribute capital to start a company. A public unlisted firm has many more owners; other companies are so big, with so many shareholders that it is hard to identify any one single owner. Perhaps the most amazing example is that of Apple, which has recently recorded the largest market capitalization of any firm in modern history – US$700 billion. One of its largest shareholders, Berkshire Hathaway owns US$7.7 billion worth of stocks. Let us say if tomorrow Apple cheats on its battery safety tests and the phone explodes in a flight, who is to blame: Employees at Apple, the CEO of Apple, shareholders of Apple, and if the shareholders are to blame, which shareholder?

Is a rabb al-maal accountable for the actions of a mudarib? In contracts of agency, is a principal completely absolved from the actions of an agent? If a teacher at a school slaps a student, is the teacher taken to court or the school also involved? In reality accountability is compromised depending on the severity of the actions involved, the severity of the damages incurred, and the influence of the principal parties involved. Has any bank CEO been arrested for the absolute fraud conducted in the mis-packaging of Mortgage Backed Securities? Was the CEO of Moody’s arrested for not looking closely at the quality of mortgages that were being packaged into various bonds? So the fundamental question remains unanswered. Where do we draw the line of accountability?

“Has any bank CEO been arrested for the absolute fraud conducted in the mis-packaging of Mortgage Backed Securities?

Was the CEO of Moody’s arrested for not looking closely at the quality of mortgages that were being packaged into various bonds?”

WHO ARE THE STAKEHOLDERS? AN EMPLOYEE’S PERSPECTIVE

There is a lot of material out there that gives information on share prices and various indicators of company performance. This is of value to owners of a company, i.e., shareholders. But how much information is available? How many media channels focus on the interests of employees? For instance, a company may be showing record earnings, but may also be laying off workers in one country and relocating jobs to destinations with cheap labour. Companies may announce a large bonus pool, but fail to announce that 70% of the bonuses were handed out to 5% of the employees, creating gross imbalances in the distribution of bonuses. It is also interesting to question some of the well-established practices, procedures and principles. For example, in the traditional cost-benefit analysis, labour is seen as a cost in the production process. Can this view be challenged? The following example may explain how tradition may be questioned. Let us assume that a company makes a profit of US$100 BEFORE WAGES AND SALARIES. How is this profit going to be shared by the HUMAN COMPONENT of the company, i.e., the employees that have all played a role in generating the profit, the managers, the directors and the shareholders. If wages of low-skilled employees, salaries of clerks, supervisors, and managers are aggregated to US$20, then in a sense 20% of profits are being shared with the lower management and other employees. If another US$30 is shared between senior managers, the smart suits who make the decisions, and the directors of the company, then their share is 30% of the profit of the company. The remainder US$50 is awarded as dividends to shareholders. It is worth asking the question if this a “fair distribution” of rewards. Who will determine what is fair? There may not be any answers these questions but it is certainly worth asking.

How should a company value the contribution of a truck driver over a computer programmer? If one listens to Nassim Taleb, one should not only reward a truck driver for driving a truck well, but also reward him, in part or full, for preventing the company from losses for doing a job well, by not banging the truck into a wall. According to Taleb, a bank teller should also be rewarded in part for not being a thief as he or she is handling a very sensitive task for the bank. The question is who represents the interests of the employees at the lower end of the corporate ladder in the board room. Senior executives have enough opportunities to brown nose directors to convince them that it is because of their unique decision-making abilities that led to company profits. However, this may not always be the case, as they may simply have been at the right time at the right place. The author once worked for a global bank based out of the UK. It had divisions like Investment Banking, Corporate UK, Corporate Europe, Corporate Global, Global Credit Card, Retail UK, Retail Global, Emerging Markets, etc. A single transaction in Corporate UK, such as a loan to Vodafone, was larger than the entire Emerging Markets Business. He recalls sitting in conference calls where each Unit Head (UH) was tooting the achievements of their departments, whereas in reality many of the corporate or even country relationships had been in place prior to the joining of the current UH. It was simply a matter of luck and being able to take credit for other people’s work, a trade mark of modern corporate life it seems. In any regards, when profits were distributed, they were unevenly shared between senior managers and the lower staff. But when massive losses were accrued by bad decisions made by the UH, lays offs were prominent amongst the lower staff, and jobs were retained by senior employees. Is this a CG issue? It most definitely is and it remains TO DATE unaddressed by modern corporate governance structures except in Germany, where a complete board, (not merely one independent director) is made up of representatives appointed by the employees of the company. This also may be one reason why German companies are the last to outsource manufacturing jobs to cheap labour destinations in India and the Far East, unlike their American counterparts.

“Sadly the importance given to the interests of employees in the Muslim world leaves muchto be desired and there is a fine line between employment and exploitation.”

Rights of employees are further compromised in situations where an employee may not be a citizen of the country in which he or she is working. A Polish employee working for a British bank in London may have little or no say in the decision-making within the company. (However, a Polish shareholder has all the rights, ownership is beyond citizenship, employment is not). A Pakistani employee in a bank in Dubai has no representation on the board of the bank or company he or she is working for. Sadly the importance given to the interests of employees in the Muslim world leaves much to be desired and there is a fine line between employment and exploitation.

CG AND SHAREHOLDERS’ INTERESTS

In the context of large companies, which are managed by a Board of Directors, the choice of directors plays an important role in determining the future of the company. Companies evolve through various processes. Some companies come into existence through legislation with the government putting up the capital for its running. Thus, the government is the initial primary shareholder. Over the years such a government owns the company, and may sell off some or all of its shares to private investors in a process called privatization. In such companies, governments typically retain a certain percentage of shareholding to retain control as the company may be strategically important to sovereign interests. Thus, representatives of the government, typically bureaucrats, can be directors on a board. In other instances, a company may have a founding father (or mother), or family, like Steve Jobs was for Apple or the Fiat family was for the Fiat Company. When these companies went public, these individuals received large percentages of stockholding, which gave them sufficient control to run the company. In other instances, money managers, hedge funds, pension funds and other such entities accumulate large shareholdings in a company. Employees may hold a large percentage by owning stock through an employee pension fund. Other companies may own large chunks of shares in the company Any company with as much as 5% of total outstanding shares can influence decision-making within the company by placing directors on the board. These directors have by definition a fiduciary duty to protect the interests of all the shareholders of the company and not just those shareholders that nominated them in the first place. So the government bureaucrats may act in the interest of the government and not the company. For instance, in the case of a semi-government-owned airline, shareholders may be more interested in taking the company public and listing its shares on international exchanges, and hiring professional management to improve revenues. The government bureaucrats, however, may resist the notion not in the interests of the company but in keeping with the interests of their employer, the government, which may view the airline as a strategic asset. Similarly, other directors may influence decisions of the company to benefit those shareholders that nominated them. For instance, an insurance company as a shareholder in a bank places a director on its board. The bank launches various products like car loans, home loans, marine loans, trade finance, etc., all of which require some form of insurance coverage. The concerned director nominates his (or her) company to be the panel insurance company for all loan-related products. However, other insurance companies may have offered better premiums in the interest of the company’s customers. Here a situation of conflict of interest lies between the bank, the concerned director and the insurance company. The director can act in the interests of the insurance company that nominated him and hence compromise the interest of the bank or vice versa. We leave it to the reader to read between the lines. No structure of checks and balances can completely encounter the conflict of interest, as one can simply incentivize a regulator to see things their way. It is a matter of human integrity. If a tyre manufacturing company is a shareholder in Mercedes, can they not influence the decisions made on the board on picking a vendor? It would be childish to assume that these positions are not taken advantage of. Even competitors own shares in one another’s companies. After all, customers keep on switching between competitors. So if one does not make money in the shape of profits from one’s own operations, they can receive dividends by holding shares in their competitors’ businesses. If iPhone loses steam, Apple can simply buy shares in Samsung to make money off their sales. Either way Apple makes money. Modern corporate governance structures have created an economic environment where 1% of the worlds wealthiest companies and individuals control 90% of the world’s wealth. So whats so Islamic about that?

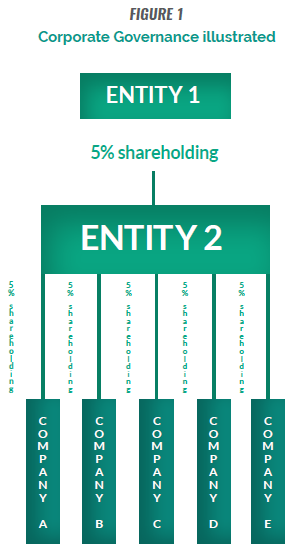

The above Figure illustrates how Entity 1, which could bean individual with resources or a company (a collection of individuals with resources) can purchase 5% shares in Entity 2, a large company. Then Entity 2, buys 5% shares in Companies A,B,C,D and E respectively. In this manner, Entity 1 also owns (albeit a diluted percentage) shares in Companies A, B, C, D and E. This structure may be good for Entity 1, and good for shareholders of Entity 2 but it allows vast financial resources to be controlled by a handful of economic entities (be they individuals or companies) and also allows these handful of companies to coordinate efforts and control natural resources, human resources and vast reserves of financial resources.

After all, when one owns 5% shares in another company, they ultimately own 5% of that companies assets, which include amongst other things their stock of financial reserves. Entity 1 with limited capital (the initial 5% holding of Entity 2) can control, influence, coordinate the economic efforts and resources of Entity 2, and Companies A, B, C, D and E in such a manne as to benefit from all their activities combined. Least of all Entity 1 can make all these companies buy shares in, or do business with, another company in which A is a primary shareholder. World domination is no longer the dream of Peewee and the Brain!

LENDERS BECOME DIRECTORS

Let us not forget that in certain countries, lenders that have large exposure to a particular company can also demand a seat on the board, as they must have interests in the company’s performance. Lenders need to get their money back. Everyone’s interests are secured except for those who work for the company. Shareholders have their interests secured, creditors have their interests secured and in fact get paid before equity holders in any case. Senior Management (the ones who are hybrids, earn a salary but also get stock options as part of their compensation packages are part employee and part owners) have their interests protected as well.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The Global Financial Crisis exposed how vulnerable we are to functioning of the financial system, and how influenced we are by the behaviour of large companies. CG provides us insight into how these companies are actually managed, how should they be managed and how powerful they actually are. One can reply that governments of well-developed countries play an important role. When RBS was accumulating billions of dollars in toxic assets, the regulatory body at the time had one individual in charge of supervising the activities of one of (at the time) largest banks in Europe. If one reads Michael Lewis’s Liar’s Poker: Rising Through the Wreckage on Wall Street, The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine, and Flash Boys, the corruption of the financial system becomes exposed in user-friendly terms.

If one thinks that American workers (probably the most empowered workers in the world) have any control over their fate, then they must read books like Exporting America or Offshoring of American Jobs and then think about their own future. The two-tier board structure which is the backbone of German companies is hardly popular in the US and is reducing popularity in Europe. Even France, which is “known to be a country where the government is afraid of its people,” is allowing its companies to opt for unitary boards. This means weaker representation for employees. Given that corporations now have more wealth than the GDP of many countries, and control more resources than households, CG structures are as important as issues of democracy, dictatorship and monarchy. It is not only an economic concern but a political one. If the reader wants to see further evidence of CG failures, they must look at wage stagnation levels in the US and in Europe for much of the past 15 to 20 years. After all, why would a shareholder readily encourage their nominee director to vote for higher wages?

Modern CG structures allow a company or an individual to control resources way beyond the individuals’ capacity to own. This is a powerful tool which like all other tools can be used for good or bad.

Petronas is the backbone of the Malaysian economy. With intelligent investments it can help insure that other companies in Malaysia are run efficiently and effectively, by becoming a shareholder of important companies. Alternatively, it can simply force a large bank to keep underwriting its bonds no matter how poorly the company is managed.

However, the Muslim world, which has yet to fully embrace the corporate culture and institutions of the OECD world, needs to be wary of the risks and the challenges that come with adopting Western economic mores. Sadly, there is no positive track record to offer as a benchmark. In certain countries, a monarch owns not only the resources of the country but also all the locally owned companies that operate in his domain. A CG nightmare. Countries like Pakistan, where some of the largest companies are state-owned going through a process of highly opaque privatization offers no relief. Therein they have what is known as a “saith” culture, where one billionaire owns the entire company, either directly or indirectly through “proxy” shareholders who may be no other than domestic servants. This, too, is a CG nightmare.

Finally, employee representation on the board can also be enhanced by customer representation, especially in the area of financial services where companies actually do business not so much with their own money but primarily with the money of others. Has anyone heard of a customer representative board member in a bank, insurance company, asset management company, whether it is Islamic or not? New mudaraba fund rules require the placement of an independent director in Malaysian Islamic banks to oversee the management of the mudaraba fund. But then Islamic banks have been migrating funds from mudaraba fund accounts to commodity murabaha fixed deposit accounts, which makes this ruling a mere exercise in futility.