There is an understanding in economics that individuals are assumed to be rational. Being rational is important in order to achieve efficiency. This principle applies to all individuals, regardless the social status, religion and age. Rationality has always been associated with being self-interested, and self-interest is always thought to have a close relationship with being materialistic. Is it really the case? This is one of the central questions Dr. Hylmun Izhar addresses in this ISFIRE Note.

RATIONALITY IN ECONOMIC THEORY

Economic theory is based on the fundamental assumption of rationality of economic agents, whether individuals, institutions or business organisations. Advanced microeconomic analyses transit from simple rationality to more complex forms of rationality based on bounded rationality and beyond. Rationality ultimately is exhibited in the choice of actions, and is not just limited to mental deliberations. Choice is rational when it is determined by a rational set of beliefs and preferences, which is defined within utility theory.

There is a close association between rationality and self-interest. Many economists perceive the motives based on something other than self-interest to be peripheral to the main thrust of human endeavour. In his work, Sidgwick (1901, quoted in McPherson and Haussman, 1996) attempts to derive utilitarianism from intuition concerning the nature of rationality. But in the end he concludes that “the method of egoism” – that is, self-interested conduct – is just rational. Similarly, Frank (2000) writes “I will use the terms ‘rational behaviour’ and ‘self-interested behaviour’ to refer to the same thing”.

There is, nevertheless, far from universal agreement on what this really means. Two important definitions of rationality are the so-called present aim and self-interest standards (Frank:2000). A person is rational under the present aim standard if he is efficient in the pursuit of whatever aims he happens to hold at the moment of action. Under this standard, assessing whether his aims themselves make any sense or not do not really matter. If someone has a preference for self-destructive behaviour, for example, the only requirement for rationality under the present-aim standard is that he pursues that behaviour in the most efficient available way. Under selfinterest standard, by contrast, it is assumed at the outset that people’s motives are congruent with their material interests. Motives such as altruism, commitment to principle, a desire for justice, and the like are simply not considered under the self-interest standard.

Furthermore, McPherson and Hausman (2000) point out a mistaken interpretation of the standard theory of rationality as a theory of self-interest. The reason is that according to utility theory, it is rational to choose whatever one prefers. Rational choices are determined by one’s own interests rather than by anyone else’s, and therefore rational choices are self-interested. Stemming from this reason, McPherson and Hausman argue that when it is interpreted as a theory of actual choices, utility theory, on this account, reveals that altruistic and moral behaviour are actually self-interested. In other word, the theory of rationality, as a matter of fact, places no constraints on what a rational individual may prefer, and therefore permits moral preferences and moral choices.

To be self-interested is to have preferences directed toward one’s own good, not simply to act on one’s own preferences. What distinguishes people who are self-interested from those who are altruistic is what they prefer, and utility theory says nothing about what the content of rational preferences ought to be. Similarly, accepting utility theory as a correct description of people’s actual choices and preferences leaves open the question of to what extent individuals are self-interested. So it appears that there is no conflict between morality and the standard view of rationality.

ALTRUISM IN ECONOMICS

Altruistic behaviour is essentially an outcome of values that include voluntary giving, voluntary service, and voluntary organisation as three main pillars of altruistic behaviour (Payton, 1988). In general sense, Miller (1988) states that the altruist (individual with altruistic behaviour) is someone who is affected by the level of welfare enjoyed by others and is moved to act on their behalf. One common characteristic from a range of definitions mentioned above is that altruistic behaviours encompass all behaviours that benefit another. One formal definition proposed by two psychologists, Macaulay and Berkowitz (1970), is “behaviour carried out to benefit another without anticipation of rewards from external sources”.

In order to give an understanding of how an altruistic behaviour can be incorporated into economic model, we present the following case study between Zubayr and Ahmed.

Suppose, for example, the case of Zubayr, who cares not only about his own income level but also about Ahmed’s. Such preferences can be represented in the form of an indifference map defined over their respective income level, and will look something like the one shown in the Figure 1. Note that Zubayr’s indifference curves are negatively sloped, which means that he is willing to tolerate a reduction in his own income in return for a sufficiently large increase in Ahmed’s. Note also that his indifference curves exhibit diminishing MRS, which means that the more income Zubayr has, the more he is willing to give up in order seeing Ahmed has more.

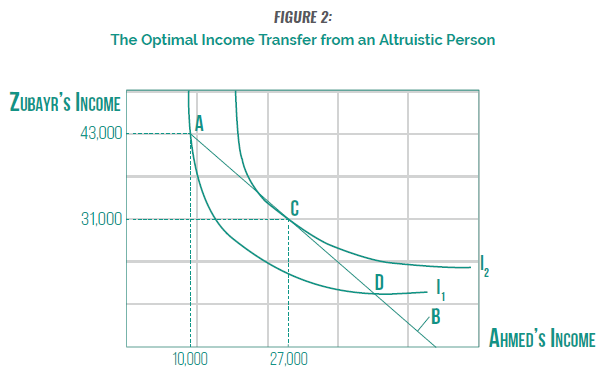

The question that Zubayr confronts is whether he would be better off if he gave some of his income to Ahmed. In order to answer this question, we first need to display the relevant budget constraint confronting Zubayr. Suppose his initial income level is £43,000/yr and that Ahmed’s is £10,000, as denoted by the point labelled A in Figure 2. What are Zubayr’s options? He can retain all his income, in which

h case he stays at A. Or he can give some of it to Ahmed, in which case he will have £1 less than £43,000 for every £1 he gives him. His budget constraint here is thus the locus labelled B in Figure 2, which has a slope -1.

If Zubayr keeps all his income, he ends up on the indifference curve labelled I1 in Figure 2. But because his MRS exceeds the slope of his budget constraint at A, it is clear that he can do better. The fact that MRS>1 at A tells us that he is willing to give up more than a pound of his own income to see Ahmed has an extra pound. But the slope of his budget constraint tells us that it costs him only a dollar to give Ahmed an extra dollar. He is therefore better off if he gives some of his income to Ahmed. The optimal transfer is represented by tangency point labelled C in Figure 2. The best he can do is to give £12,000 of his income to Ahmed.

However, the conclusion would have been different if Zubayr had started not at A but at D in Figure 2. Then his budget constraint would have been only that portion of the locus B that lies below D. Hence, he does not have the option of making negative gifts to Ahmed. And since his MRS at D is less than 1, he will do best to give no money to Ahmed at all. (Such outcome is called corner solutions).

How can an altruistic person maximise his utility? This question will be answered in the following model.

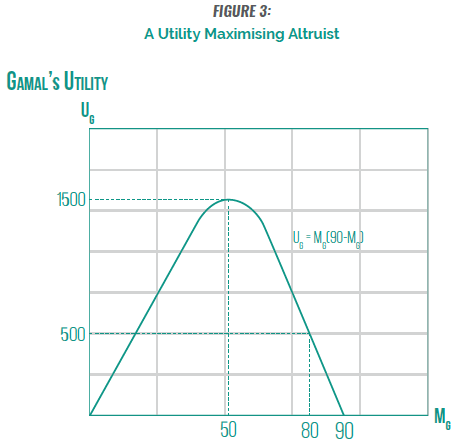

Gamal’s utility function is given by UG=MGMH, where MG is Gamal’s wealth level and MH is Hamid’s. Initially, Gamal has 90 units of wealth and Hamid has 10. If Gamal is a utility maximiser, should he transfer some of his wealth to Hamid, and if so, how much?

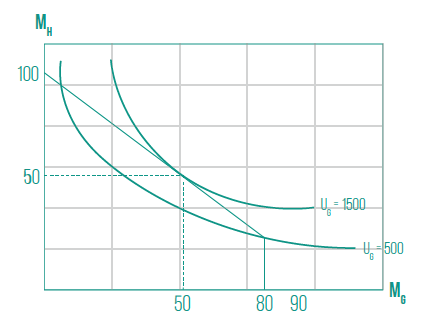

The following figure depicts Gamal’s initial indifference curve and the indifference curve when each has 50 units of wealth. It also draws Gamal’s budget constraint in the MGMH plane.

Suppose, Gamal and Hamid have a total of 100 units of wealth. This means that if Gamal’s wealth is MG, then Hamid’s is 90-MG. Gamal’s utility function may thus be written as UG=MG(90-MH), which is plotted in the top graph of Figure 3. Note that Gamal’s utility attains a maximum of 1500 when MG=50. At the initial allocation of wealth, Gamal’s the bottom graph is Gamal’s budget constraint in the MGMH plane. Note that the UG=1500 indifference curve is tangent to that budget constraint at MG=50.

Being altruistic, as theoretically proven, has been proven to be an instrumental means to enhance an economic agent’s wellbeing. In a microeconomic perspective, it, not only enhances the consumption capacity of individuals, but also their productive capacity. Furthermore, it is found that sharing a certain portion of wealth to other individuals can; in fact, increase the level of utility of individuals. Hence, being altruistic is also rational.