Introduction

Derivatives are contractual arrangements between two parties, whose value is derived from a reference parameter, be it stock, commodities, indices, currencies etc. It can be used for either hedging, speculation or for arbitrage. Although Islamic finance, according to its basic tenets, is adverse to the use of derivatives for speculative purposes (by reason of excessive risk-taking or Gharar), they are needed by the industry: companies, as well as banks, need effective hedging tools, whether they are geared towards Shari’a-compliant conduct of their business activities or run on conventional grounds.

Over the last years there has been a strong push into a further development of Islamic derivatives. Initially disputed by some as an overall concept and deemed in contradiction to Shari’a, there are nowadays a number of structures which have been approved by Shari’a boards across the globe. Without reaching unanimity on the topic, certain classical Islamic instruments are in use for engineering pay-offs which are similar to conventional derivative contracts, such as swaps, forward contracts etc.

Prominent Islamic instruments in this context are:

- Wa’ad, i.e. the unilateral promise or, legally speaking, the undertaking by a party to enter into a future transaction at the election of the other party.

- Arbun, i.e. “earnest money” or a non-refundable down payment, rendered in view of a future sales transaction which shall work as an incentive to the prospective buyer to eventually enter into the envisaged sales contract. However, there is no further obligation on the arbun-buyer to enter into the sales contract. At its maximum the buyer may lose the down-payment in case he opts not to enter into the subsequent sales transaction. If the sales contract is concluded, the down-payment is deducted from the purchase price.

- Salam, i.e. a sales contract, in which a specific type of good in a specified quantity is sold in view of a future defined delivery date. The purchase price has to be paid in full in advance.

The majority of structures rely on commodity mura- baha which serves as a building block for facilitating the required cash flows. Commodity murabaha had come under scrutiny since its use in modern Islamic banking is considered akin to monetization or tawarruq which, according to the applicable AAOIFI Shari’a Standards (No. (8) and No. (30)) and a recent OIC Fiqh Academy ruling would only be permissible under relatively tight conditions.2 The industry did not and does not al- ways comply with these requirements. However, since no other equally viable instrument seems to be in place in structuring (mark-up) cash flows3, commodity murabaha remains a tolerated means of building-up Shari’a- compliant structures in contemporary Islamic finance.

Lately, major market players developed standard docu- mentation for the purpose of facilitating the use of derivatives in Islamic finance. The most prominent standard contracts have been developed by IIFM / ISDA:

- The ISDA / IIFM Tahawwut Master Agreement (“TMA”) was developed by International Swaps and Derivative Association, International Islamic Financial Market and major international market players and de- livers a framework agreement similar to conventional ISDA Master Agreements which, when developed further, could be used for a variety of Islamic derivatives. According to the Schedules developed to date, the

TMA allows the documentation of an Islamic Profit Rate Swap4 and an FX Swap.

– The IIFM Master Murabaha Agreement (with related Master Agency Agreement for the Purchase of Commodities and a Commodity Purchase Letter of Un- derstanding) can be seen as a proposition on how to document interbank or corporate lending based on commodity murabaha.

While the TMA is considered a true leap forward in terms of how sophisticated Islamic derivatives could be documented, the IIFM Master Murabaha Agreement is not likely to gain comparable importance.

Firstly, because the IIFM Master Murabaha Agreement has to compete with other tried and tested contractual arrangements and enters the stage at a very mature stage in terms of commodity murabaha documentation.

Secondly, market standards usually incorporate the agen- cy aspect for the underlying commodity trades rather than documenting this through a separate agency agree- ment, which adds heavy documentation and requires further signatures. Therefore, the IIFM Master Murabaha Agreement might at best prove successful in the area of corporate lending, since a corporate may not dispose of their own tailored agreements. However, in the inter- banking market, commodity murabaha is likely to remain documented through home-tailored agreements already in use in the market. This is further supported by market practice in Islamic inter-bank lending according to which the depositing party (i.e. the murabaha buyer) usually im- poses its murabaha documentation on the lender. This further restricts the prospect of a wider use of this docu- mentation throughout the industry.

Variety of structures for Shari’a-compliant derivatives

GIFR 2010 (Chapters 14 and 15) delivered in-depth in- sights on how derivative structures based on the above classical fiqhi contracts work.

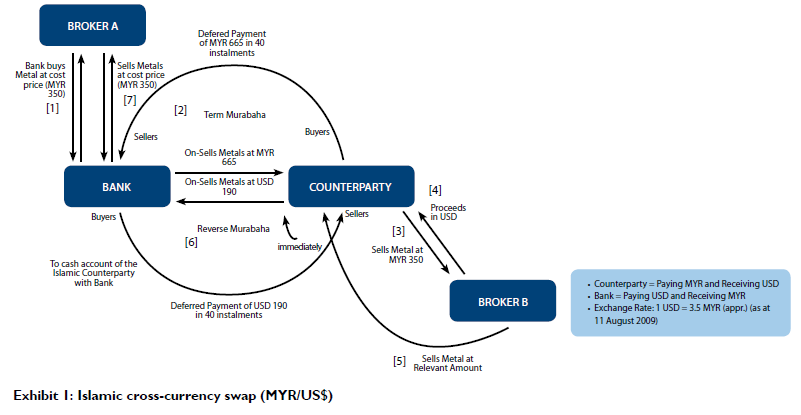

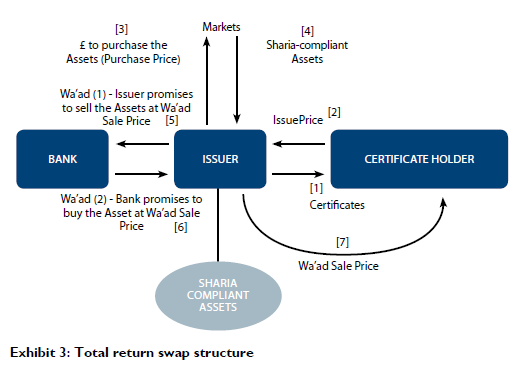

In terms of a recap the below exhibits provide an over-view on the most common structures.

These structures rely on a combination of sets of com- modity murabahas and / or sets of wa’ad to enter into the purchase or sale of Shari’a-compliant commodities or other assets.

- Lack of express guidance from leading standard-setting bodies (AAOIFI, ISFB)

Despite the fact that the widespread misuse of derivatives is by and large identified as a major trigger to the current financial crisis which by contagion quickly spread into the “real economy”, major industry organizations in the field of Islamic finance, i.e. AAOIFI and IFSB, have not yet issued any express statement regarding the structuring or the use of such instruments.

Also, neither AAOIFI nor IFSB have issued any standard on wa’ad, which further causes a prolific use of this Islamic instrument for structuring complex and, as the case may be, cutting-edge transactions.

Across the board two generic stances can be extracted with regards to the assessment of the role of derivatives in the current environment: Stance A: The misuse of derivatives is one of the most prominent roots of the current economical crisis.

“[…] A revolution in packaging and distributing credit-based instruments was underway. It was called “financial innovations”. We all believed in the fallacy that these sophisticated tools and instruments would create value. Apparently and in hindsight, the value they created was mostly illusory and in turn was a prelude to the boom in shadow banking which was mainly based on excessive leverage. It was a textbook-style manifestation of regulatory sabotage. […] a detachment between what is real and what is financial. This decoupling notion which is different from the one prevailed at the advent of the crises was the catalyst for what had to come a full-blown economic, financial and social imbalance for us to deal with for the next generation. […] Our efforts should center on how we better serve the real economy. We believe we can do without those synthetic instruments that contributed in bringing the whole financial system down to its knees.”

Stance B: Islamic finance is in dire need of effective risk management instruments and therefore has to embrace Islamic derivatives as the only viable mean of facilitating such effective risk management.

“To the extent there are not enough Shari’a-compliant liquidity and risk management products, then clearly Islamic finance would be disadvantaged compared to conventional banks and would be less able to manage their liquidity risks.”

The above observations complement each other rather than contradicting themselves: Islamic finance needs derivatives for efficient hedging, yet, the question is how to contain these financial “weapons of mass destruction”.

Surprisingly, the two major standard-setting bodies in terms of Shari’a-compliance, AAOIFI and IFSB, to date have not issued a comprehensive framework or issued at least a single statement dedicated to sophisticated Islamic derivatives.

As regards AAOIFI, newly issued rules deal indirectly with the issue: the new Shari’a Standards comprise now a specific standard (Standard No. 31) on “Controls on Gharar in Financial Transactions”. According to the prescription of gharar, risk-taking in its excessive form is prohibited. In view of the use of derivatives not only for hedging and arbitrage, but also for speculation, this standard seems to be at least indirectly linked to the universe of Islamic derivatives.

A glance at the new AAOIFI Standard reveals the following:

“(4) Gharar violated the transaction when it satisfies the following four conditions:

- If it is involved in an exchange-based contract or any contract of that nature.

- If it is excessive in degree.

- If it relates to the primary object of the contract.

- If it is not justified by a Shari’a-recognizable necessity”. And:

“(4/2/1) Gharar is excessive when it becomes a dominating and distinctive aspect of the contract, and is capable of leading to dispute. However, assessment of gharar for such purpose could differ according to place and time, and has to be determined in the light of normal practice (urf). […] Gharar in any of these forms sets the contract null and void.”

Lastly:

“(4/4) Need in this context (which could be public or private) refers to the situation when refraining from commitment of Shari’a-banned gharar leads to severe hardship, though may not amount to mortality. Need should also be inevitable, i.e., there should be no Shari’a-permitted way of accomplishing the task, except through the contract that involves excessive gharar. Commercial insurance, in the absence of takaful (solidarity insurance) can be cited here as a fitting example.”

In this context, though beyond the scope of this chapter, it could be of interest, on whether the win-lose- probability involved in modern-day derivative contracts would qualify as “excessive gharar” due to the above definition. Further, the question on whether or not the absence of comparably effective Shari’a-compliant risk management and hedging solutions could trigger the use of cutting-edge structures by reason of maslaha (public interest) and darura (public need), as being addressed in (4/4) above, is a topic Shari’a boards will have to take into account in their further assessment of sophisticated derivatives structures as those outlined above.

be proven and such practice will deliver further insights from a more scholarly point of view, which would go beyond the scope of this chapter.

In summary, we observe that despite the importance of Islamic derivatives for effective risk management guidance throughout the industry, major standard-setting bodies have not yet delivered a comprehensive statement on their view towards such instruments, but have issued new rules which are yet to be tried and tested in practice.

Contrasting the somehow rudimentary standardization, the market itself lately leaped a great deal forward in terms of convergence by market practice through the delivery of a standard documentation for Islamic profit swaps: the so-called Tahawwut Master Agreement developed after several years of working group efforts by ISDA and IIFM (“TMA”).

- Increasing market standardisation by ISDA Tahawwut Master Agreement as important step forward

The TMA features a similar documentary approach as the 2002 ISDA Master Agreement but is designed to be consistent with Shari’a principles.

The outlines of the TMA follow largely a conventional ISDA Master Agreement but also contain specific terminology and features relating to the specific design of Shari’a-compliant derivatives transactions.

Major issues which had to be dealt with during the working group discussions (which lasted several years) were, among others the design of a structure accommodating the distinction between done deals and future transactions which, under Shari’a, must not be considered separately.

A transaction under the TMA will technically follow the mechanisms described above, i.e. it is essentially based on the concept of unilateral promises (wa’ad) to enter into several commodity murabahas over the lifetime of a transaction. In the framework of the TMA, “Transactions” (i.e. concluded murabaha transaction) and “Designated Future Transactions” (i.e. not yet concluded murabaha transactions to which a party commits to enter into in the future) are clearly demarcated. In addition to the above, the parties agree via a further set of unilateral promises to enter into so-called musawama8 transactions if, e.g. due to an event of default, the contractual arrangement has to be terminated earlier than scheduled at the outset. Under a musawama transaction, a party commits to buy a specified quantity of a specified commodity at a price, which is determined according to a specific formula contemplated in the agreement.

From the point of view of the above structures in use for engineering Islamic derivatives, it may be questionable whether their win-lose character (featured by all derivatives contracts) makes them contain gharar as “dominating and distinctive aspect of the contract” (AAOIFI Shari’a Standards No. (31), (4/2/1)). Since this AAOIFI Shari’a Standard has been published only very recently, its implementation by Shari’a boards has yet to The significance of the TMA for potential convergence throughout the Islamic finance industry cannot be underestimated. As opposed to murabaha master documentations such as the one launched lately by IIFM, the TMA enters the stage when only a few players had yet developed similar documentation. Therefore, and also due to the strong presence of ISDA as “convergence agent” (by setting standards and providing documentation) in the conventional derivatives markets, the TMA can be considered a true leap forward for developing Shari’a-compliant derivatives and will encourage new participants to enter the market, both on the buy-side and at the supplier’s end. The documentation remains work-in-progress: ISDA so far only provides Schedules allowing for documenting Islamic profit rate swaps or FX swaps. Expectedly, and with more wide-spread market practice, the industry will develop more Schedules in order to benefit from the modular nature of the ISDA framework. From a more technical/legal point of view, further work needs to be done in order to develop suitable collateral documentation (Credit Support Documentation) together with netting opinions, assessing the close-out mechanism in the relevant jurisdictions.

In terms of transactions costs, the fact that the TMA delivers a ready-to-use contractual framework which is available for relatively complex transactions, this will further reduce the “Shari’a-premium” to be paid by its us- ers in the past for such transactions (i.e. documentations costs), therefore directly serving the competitiveness of the Islamic derivatives industry.

To date the TMA has not yet gained sufficient traction in the market which is understandable since the documentation is still at a relatively nascent stage (the final documentation was only made available by end of Q1 2010) and the market will have to prove to which extent it wants to make use the documentation in its transactions.

The TMA, even though being in several respects similar to the ISDA 2002 Master Agreement, will have to be tried and tested in courts in its own right, which may add or reduce its credibility in the market. This accounts particularly for the Shari’a-specific features of the documentation.

The market for sophisticated Islamic derivatives as a primary OtC market lacking widely used standardized contracts and sufficient volume

- OTC market lacking widely used standardized contracts

The market for sophisticated Islamic derivatives, other than commodity futures like, notably, the crude palm oil futures contracts (FCPO) traded on Bursa Malay- sia, is an OTC market (as opposed to a market where such financial instruments would be exchange-traded). In contrast to conventional markets for sophisticated derivatives markets where master documentation is in use with respect to non-commercial terms and further product-specific schedules are offered for documenting the commercial terms (cf. ISDA 2002 Master Agreement), comparable Islamic derivatives have been fully tailor-made in the past.

As an OTC market at a nascent stage, the market for more sophisticated Islamic derivatives remains in terms of size and commercial terms a very opaque market with a wide array of structures and differing levels of sophistication in terms of Shari’a-monitoring. It caters for a mixed crowd of Islamic and conventional players, for corporates and banks, for true hedgers, arbitrageurs and – presumably – speculators. Transparency and overall volume are the primary challenges to enable the market for Islamic derivatives to reach the critical mass required for kicking-off in terms of scale effects and liquidity.

- Tradability and trade in sophisticated Islamic derivatives

The market for sophisticated Islamic derivatives is a market without trading activities in the sense that parties used to enter into a derivatives contract and stick to this agreement until expiry of the respective contract. Given that until the issuance of the TMA, there has been a complete lack of standardized contracts in the field of more sophisticated Islamic derivatives, this is not surprising. Without standardized contracts used in the market and a secondary market respectively, any trading activity would prove cumbersome as such tailor-made contracts may be suitable for one party but may not necessarily be suitable for another party. Conventional markets faced similar restrictions in their early stages when by the lack of standardized contracts, derivatives had not yet reached the quality of negotiable instruments.

In the long run, the TMA could change this picture, since it introduces a comparable modular approach as known from its conventional counterpart (e.g. ISDA 2002 Master Agreement) to the sphere of sophisticated Islamic derivatives.

To date, the markets in sophisticated Islamic derivatives have not significantly kicked off despite the release of the TMA. Supposing a future market on such instruments would eventually reach a higher level of liquidity and volume, the question could arise on whether instrments like Islamic profit-rate swaps or Islamic FX swaps would be tradable under Shari’a. Since the above structures mostly rely on underlying commodity murabaha contracts, their tradability would be restricted in the sense that trading would be allowed once the underlying murabahas have matured, whereas during the life of a murabaha contract this would be considered as trading in debt (bay al-dayn) which is proscribed by Shari’a.

Outlook

- De facto standardisation by market practice (TMA)

As stated above regulatory standards on derivatives from major standardisation organizations (AAOIFI, IFSB) are still non-existent.

In contrast, the market itself has been moving forward

towards convergence by creating a potentially new market standard by the launch of the TMA recently. To date this template documentation is still incomplete in various respects (i.e. more product-specific Schedules, availability of credit support documentation etc.) and yet has to be tried and tested in courts to gain more confidence by the industry. Despite these apparent gaps it appears that the new standard documentation, both in its contents as well as in the way it has been manufactured (as a true East-West joint effort), the TMA indicates the way for- ward for standardisation in Islamic derivatives and could be used as a role model for further overall convergence.

The level of sophistication of the TMA and its architecture as potential multi-product documentation (as soon as more product-specific Schedules will be available) point towards a consolidation of future structures to be used for Islamic derivatives. Since the TMA relies on wa’ad, murabaha and musawama as key Islamic contracts, other structuring options, e.g. salam, are likely to run out of practice for the Islamic derivatives industry.

- Challenges arising from reduced market volume and a fragmented market

In the first place, derivative markets exist because hedgers seek protection and arbitrageurs are in the quest for profit based on market inefficiencies. Additionally, there is significant headroom left for speculators as additional market participants. To date, Islamic derivatives, due to the Shari’a proscription of the trading of debt, cannot be traded according to the majority of scholarly views on this matter. The Malaysian market, where Shari’a-compliant palm oil futures contracts have been deemed permissible as early as 2003,10 is not likely to change this picture with respect to the less lenient centres of Islamic finance, in particular the Middle East.

Solutions are hard to be found from a classical fiqhi perspective, since the proscription of trading in debt (bay al-dayn) is, for a large number of scholars, perceived as one of the cornerstones of Islamic finance. There- fore, the buy-and-hold character which applies to most Islamic financial instruments based on commodity murabaha is likely to continue monopolising the markets for Islamic derivatives for the near future. In terms of the further development of the Islamic derivatives markets, in particular with respect to pricing and liquidity, these restrictions will continue to be one of the major obstacles for an increase in market efficiency in Islamic financial markets, including Islamic derivatives markets.

The journey towards a full-grown Islamic financial universe has gathered pace only one and a half decades ago. We stand now at a market size of around USD 1.13 trillion, whereas the critical mass in terms of market liquidity and scale effects on transaction costs would require much more. Discussions on issues of market transparency, e.g. by coordinating the establishment of trade repositories for credit, rates and equity products, which are currently underway for the conventional derivatives market are yet to be kicked-off in the Islamic derivatives markets.

The global financial crisis has put conventional financial precepts on trial. Islamic banking, for a number of inherent values, has been struck to a significantly lesser ex- tent. Despite the fact that Islamic finance still has a long way to go to reach efficient liquidity and risk allocation for the underlying “real economy”, important steps have been accomplished over the last twelve months. The settling-in of a broader base of acknowledged structures for Islamic derivatives and the emergence of a multi-product documentation which, in terms of sophistication, can aptly compete with conventional derivatives instruments (ISDA / IIFM Tahawwut Master Agreement) are milestone achievements. Yet, the markets have to gain more experience with the use of these instruments and structures and their documentation.

From a scholarly perspective, relevant standardisation organizations (i.e. AAOIFI, IFSB) will have to further promote a continuous debate on the use and the tradability of these instruments. Standardisation organizations should live up to the unique opportunity to be instrumental in a further careful development of Islamic derivatives which truly serve the needs for hedging and efficient risk management in the aftermath of the global financial turmoil.